Oregon’s D.A. Elections Mock Democracy, Again

DAs keep resigning in election years, and governors keep appointing deputy prosecutors who then get to face voters as incumbents. It happened again this year.

| May 7, 2020

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

District attorneys keep resigning heading into election years, and governors keep appointing deputy prosecutors who then get to face voters anointed as incumbents. The pattern is in full force in Oregon’s May 19 elections.

As public opinion shifts away from “tough on crime” politics, prosecutorial elections are upending the criminal legal system. They have brought to power public defenders and civil rights attorneys and rewarded candidates who ran on reducing incarceration, a trend that now extends well into suburban and rural counties.

In Oregon, though, a longstanding dynamic is stymying electoral change and keeping the public’s appetite for reform at bay.

District attorneys keep resigning shortly before their terms conclude. And governors keep filling these vacancies by appointing deputy prosecutors—often one of the departing DA’s lieutenants—who then get to face voters for the first time as incumbents. That’s an enviable advantage that dissuades others from running and sidelines critical voices that would break the mold of Oregon DAs, whose association has championed punitive policies and fought reform proposals.

This pattern of handing over the reins of DA offices to heir apparents is in full force in the Oregon elections that are just around the corner, on May 19, an Appeal: Political Report analysis found.

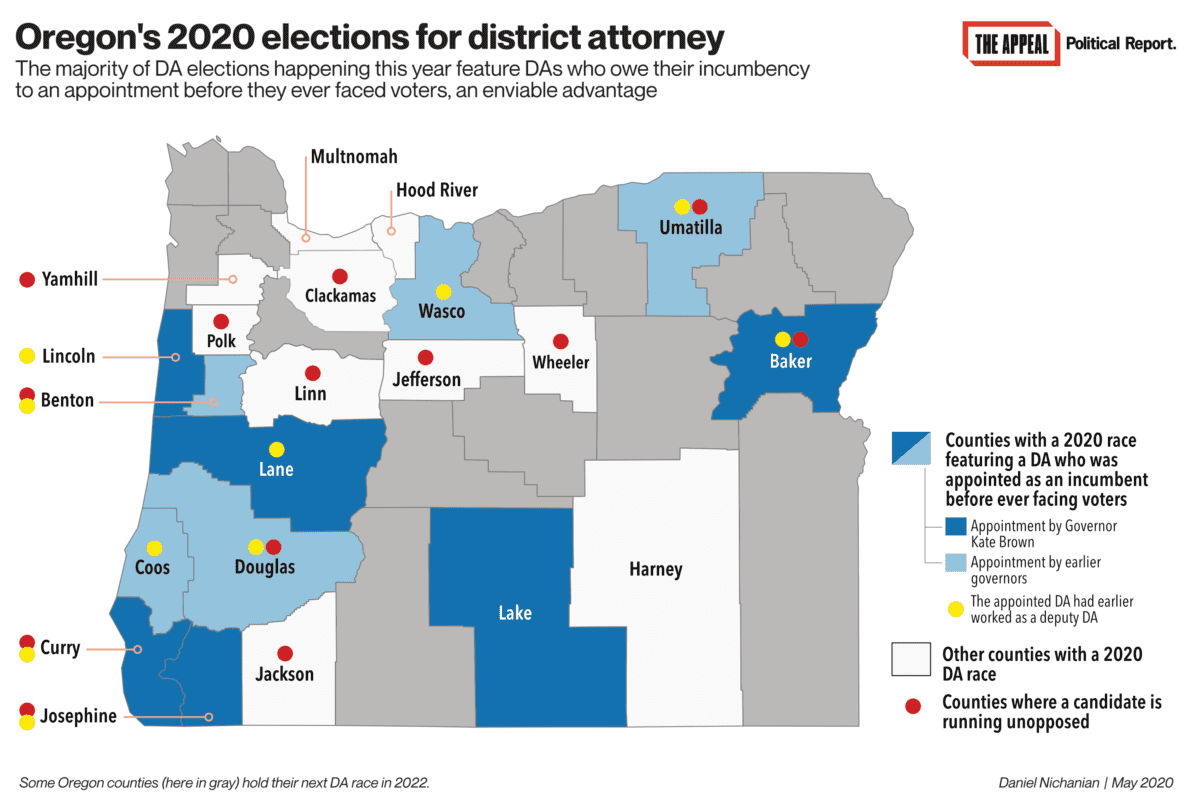

Of the state’s 21 county-level DA elections, 11—a majority—feature an incumbent who rose to be DA through an appointment before ever facing voters. Nine of them already worked as deputy DAs in the same office, and a 10th was a prosecutor elsewhere. Seven of them are running unopposed.

These numbers, which include five appointments that Governor Kate Brown has made since July, ensure that May 19 will largely affirm Oregon’s prosecutorial status quo. (Our Oregon master list contains a database of who is running for DA and their backgrounds.)

The organizing around DA races throughout the country has overhauled conventional expectations of who should be prosecutor. Last year, in Virginia’s Loudoun County, Buta Biberaj was attacked for working as a defense lawyer, but she went on to beat the county’s chief assistant prosecutor. That same day, Chesa Boudin and Jim Hingeley, two public defenders who like Biberaj ran on reform platforms, won in San Francisco and in Albemarle County, Virginia.

“It’s that background [as a public defender] that has made me sensitive to the issue of family separation because so many of the people I’ve represented were deeply affected by their incarceration, and their prospects for success after incarceration were very considerably diminished,” Hingeley told the Political Report at the time. “I saw families that were torn apart, and I saw the consequences of that.”

To be sure, many of the country’s reform-minded DAs have backgrounds as prosecutors. But in Oregon, the quasi-systematic promotion of staff prosecutors shuts the door to debates about qualifications. It boxes out people with other backgrounds and people who have worked in capacities that familiarize them with alternatives to criminalization.

And the widespread appointments of individuals who have worked under the resigning DAs further compound this closure to outsiders.

“There are two layers to why this is harmful,” said Bobbin Singh, executive director of the Oregon Justice Resource Center, a group that advocates for criminal justice reform. “One, you don’t get any new and innovative thinking into an office when you pull up someone who is next-in-line. … Second, it creates all the wrong incentives in the office. Folks who are interested in advancing their career will do what the current DA is doing to advance themselves. … You are teaching people to fall in line.”

Singh added, “The practice that has been created with these appointments, and with bringing people up within the office, has entrenched a culture that is stuck in the 1990s, with an antiquated understanding of criminal justice.”

When Alex Gardner resigned as DA of Lane County (home to Eugene) in July 2015, Governor Kate Brown appointed as his replacement his chief deputy Patricia Perlow, a prosecutor in that office since 1990; the switch came just 10 months before the 2016 elections.

Since then, Perlow has been a consistent and vocal foe of the criminal justice reforms proposed in the legislature; last year, she spoke up against bills to restrict the death penalty and the adult prosecutions of children.

This song-and-dance recurred over the past 10 months, heading into the 2020 cycle.

With regularly scheduled DA races looming in Curry and Josephine counties, for example, incumbents resigned and Brown appointed deputy DAs from their offices to take their place. Both appointees are now running for a full term unopposed. In Baker County, Brown filled a vacancy by appointing a deputy DA from another county. He, too, is now running unopposed.

—

If the past is prologue, they can expect to remain in office for as long as they wish.

Benton County DA John Haroldson, Coos County DA Paul Frasier, and Umatilla County DA Daniel Primus have never faced a single opponent, despite being on the ballot a combined eleven times since their appointments. Haroldson and Frasier were their county’s chief deputy DAs in 2007 when their bosses resigned and Governor Ted Kulongoski appointed them; Primus was Umatilla County’s chief deputy DA in 2011 when Governor John Kitzhaber promoted him.

It’s not that no one else wanted the job. Kulongoski chose Haroldson and Kitzhaber chose Primus over other potential appointees who had expressed interest, but no one then challenged them at the polls.

“Often there’s an expectation that this person just is anointed into the new role,” said Kelly Simon, legal director of the ACLU of Oregon. “If a person from inside the office culture has the inside advantage in an election, it makes it harder for the public to shift that culture if they want to.”

Once in office, incumbent prosecutors everywhere often go unopposed, as documented by a recent nationwide report by the University of North Carolina’s Prosecutors and Politics Project. In smaller counties, this can stem from a reluctance on the part of lawyers to jeopardize their careers by defying the chief prosecutor of the county where they practice.

—

This year, the big exception to Oregon’s pattern of vacancies and gubernatorial appointments is Multnomah County (Portland). DA Rod Underhill announced that he would not seek re-election but he did not resign, and there is a competitive open race to replace him on the May 19 ballot.

Brown, the governor, has endorsed Michael Schmidt, the more progressive candidate, rather than Ethan Knight, who is running with Underhill’s support.

“Usually the sitting DA won’t step down unless they know their deputy or their next-in-line will be appointed,” Singh said. He added, “It’s hard for me to know how much intention there is behind that, as far as it being an intentional strategy. But it has been part of the culture without question.”

In 2018, The Appeal reported on evidence of coordination in Massachusetts between the governor and a DA who negotiated his deputy’s appointment before resigning in an election year.

The Political Report knows of no such coordination between governors and prosecutors in Oregon. Instead, what is striking about Oregon is that the historical patterns of gubernatorial appointments are already public knowledge.

Oregon DAs are likely to know about this history from their own experience, or from knowing about their peers’ backgrounds. When Primus got the news that Kitzhaber was appointing him in 2011, he was at an Oregon District Attorneys Association conference.

In 2016, the ACLU of Oregon released a comprehensive report on the frequency of DAs being appointed before ever facing voters, and of deputy DAs landing gubernatorial appointments. “On the job experience must count for something, but when does continual promotion from within constrain progress and needed reform?”, the report asks before laying out some of the ways in which Oregon DAs “were intensely opposed to the reform conversation and forcefully defended the system they most control.” This report gained some media coverage at the time.

The resignations have continued to flow in.

In the run-up to 2018, when a different batch of 16 counties voted for their DAs, Brown appointed four DAs who then ran as incumbents. (All went unopposed.) Three of them were deputy DAs, though none in the county where they were appointed. The fourth, EveLyn Costello, was a defense attorney whom Brown appointed in Klamath County over a deputy DA who also sought the position. She said Costello would bring a “fresh perspective.” Still, in the run-up to 2020, Brown was more likely to promote deputy DAs who had worked within the same office: Those were three of her appointments, though one of them also worked as a defense attorney in between. She has also appointed a prosecutor who had worked elsewhere (in Baker County) and a private attorney (in Lake County).

Brown’s office did not respond to a series of questions on her history of DA appointments.

“DAs have an incredible amount of power in deciding how our criminal justice system operates and what values it will reflect,” Simon, of the ACLU, emphasized. “And I think that the choices of what values should be reflected in our DA offices should come from the voters.”

Singh suggested that Brown and future governors should vow that, when faced with a vacancy, they will only appoint DAs who intend to not seek full terms. “My guess is this would prevent district attorneys from resigning early,” he said.