In 2022, Intense Clashes Between Criminal Justice Reformers and Tough-On-Crime Foes

Eight big election questions that will shape the future of criminal punishment and mass incarceration

| February 8, 2022

In a span of 13 months in 2020 and 2021, New Orleans elected a district attorney who vowed to break with the office’s “tough-on-crime” legacy, two local judges who were working as public defenders, and a sheriff who ran against the jail’s dismal conditions to oust the incumbent. Each result taken on its own was a triumph for the local activists pushing against the city’s extraordinarily punitive status quo.

Taken together, they signaled a new chapter in the political battles over criminal justice reform and decarceration.

As more candidates win these offices on outsider platforms that involve reducing incarceration and ending cash bail, they are chipping away at the isolation that greeted their initial wins, and building on each other’s successes. Organizers too are now fighting on many fronts up and down the ballot, targeting DAs, sheriffs, attorneys general and even high bailiffs.

But proponents of a more punitive approach are also scrambling to stop these candidates and thwart them once they win. They are invoking a recent rise in murders to defend more draconian policies, even if the increase also took place on the watch of officials who implemented no reform. Within days of carrying Virginia last November, the new Republican attorney general cast it as a top priority to target the state’s reform-minded prosecutors. Even as Philadelphia DA Larry Krasner easily won re-election in 2021, critics of San Francisco DA Chesa Boudin (arguably the nation’s most visible decarceral DA after Krasner) have forced a recall vote against him this summer.

In 2022, that clash between reformers and tough-on-crime opponents will continue to play out across the nation, and shape the criminal legal system in dozens of electoral battlegrounds.

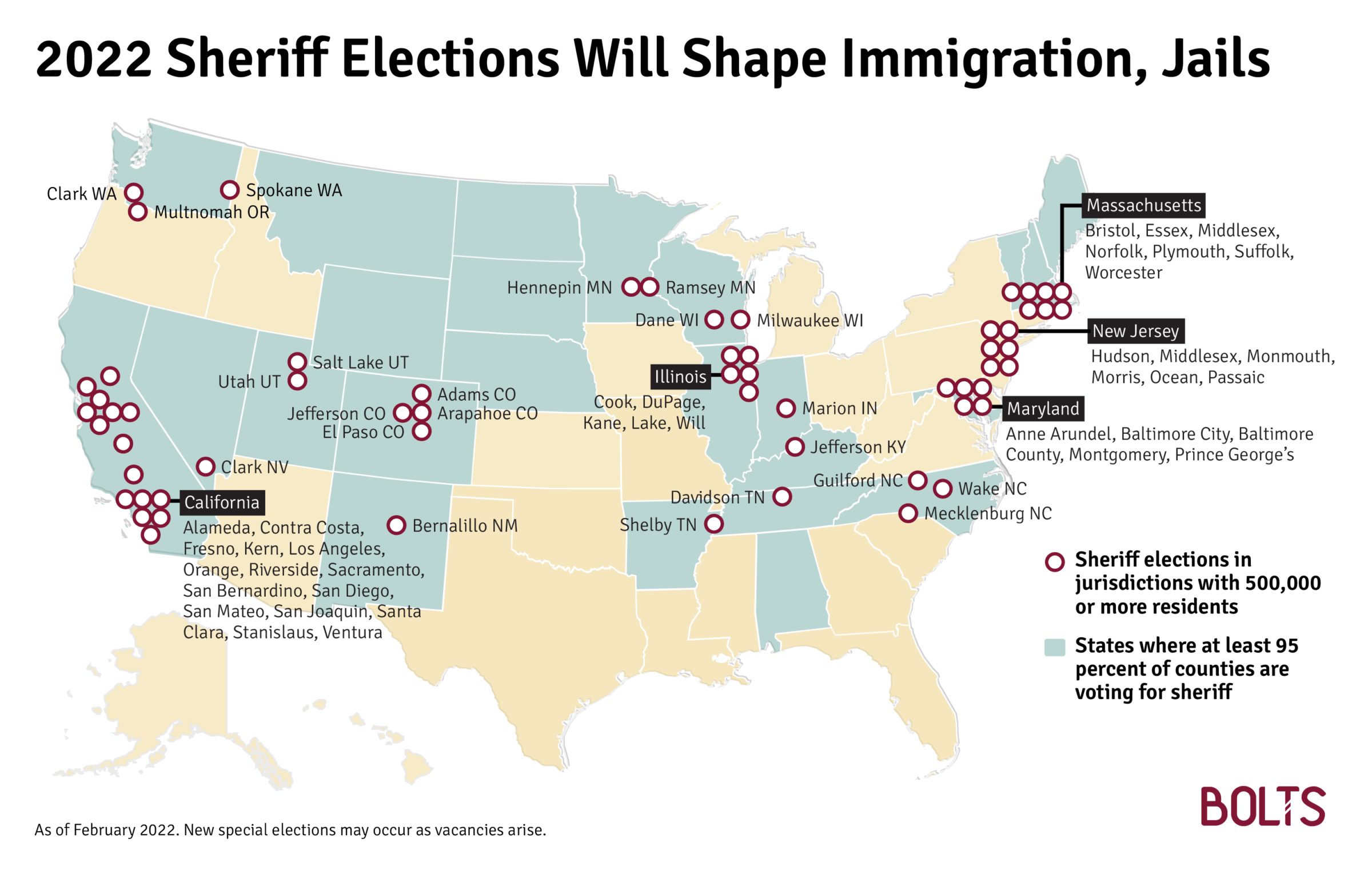

There are more than 2,400 elections just for prosecutor and sheriff in 2022 (the list of these elections is available in a new Bolts database). These offices wield tremendous discretion over incarceration and law enforcement, and major battles are already brewing over how to use this power from Boston and Raleigh to San Jose and Las Vegas.

These electoral conflicts extend into new territory this year. Reformers seek to build upon the sparks of success they’ve had in judicial races since 2020. And while politicians who want to maintain or increase police funding largely prevailed in mayoral elections last year, new races could test the bounds of municipal police reforms in Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles.

Bolts will cover these races and their outsized consequences throughout 2022. To kick off our midterm coverage, below is a preliminary guide to eight big questions that will define how criminal justice issues fare at the ballot box this year.

1. Can reform prosecutors continue their rise, or will they face setbacks?

Only a few years ago, it stood out whenever public defenders ran for DA or when candidates espoused platforms of slashing incarceration. But now many are sitting in office, and reformers are the incumbents playing defense in some places.

Take Rachael Rollins’ trajectory. She became DA of Boston after vowing during her 2018 campaign to not prosecute a list of low-level offenses, which felt novel at the time for a DA but has since grown more common among progressives. In 2021, President Biden appointed Rollins as U.S. Attorney, and she was confirmed in the fall over the objections of Republican senators.

Rollins’ rapid rise testifies to a leftward shift on criminal justice. However, it also means local progressives have to start over since she can no longer run for re-election this year. Boston is one of the places where reformers risk losing ground in 2022. San Francisco voters will decide whether to recall their DA, Boudin, who has drawn sustained fire since 2019 from opponents who include tech business leaders, the retail industry, and the mayor. Wesley Bell is up for re-election in St. Louis County four years after ousting the prosecutor who did not press charges against the police officer who killed Michael Brown in Ferguson.

In dozens of other elections this year, the policies that fuel mass incarceration remain in the hot seat.

Many states elect all or nearly all of their prosecutors in 2022, and a new crop of reform candidates are pressing their case for major shifts in the status quo.

In some places, it’s been decades since voters were last asked to shape the local criminal legal system. Pinellas County (St. Petersburg), home to nearly one million Floridians, will host its first contested prosecutor race in 30 years because a public defender has jumped in the race.

Public defenders are also running for prosecutor in Santa Clara County (San Jose), California, Prince George’s County, Maryland, and Hennepin County (Minneapolis), Minnesota, where chief prosecutor Mike Freeman is not seeking re-election two years after facing protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. Outsiders are also trying to take over other DA offices, including a civil rights attorney in Alameda County (Oakland), and a former advocate at the ACLU of Massachusetts, who is challenging a vocal foe of reform in Plymouth County.

Incumbents who have long drawn criticism from reform advocates for their punitive policies are also up for re-election in Clark County, Nevada, and Shelby County, Tennessee. In the latter, prosecutor Amy Weirich drew national attention last week for trumpeting the six-year prison sentence for a Black woman who had registered to vote despite a past felony conviction.

And the list goes on. North Carolina’s two most populous counties have Democratic primaries that are full of contrasts. Dallas has drawn the same three-candidate field as 2018. Open seats may be hotly disputed in Essex County, Massachusetts, Hidalgo County, Texas, Sacramento County, California, and King County, Washington (Seattle). And because nothing is ever simple in local governments, you may need to keep track of two entirely separate but hotly contested races in Baltimore City and Baltimore County.

2. Will sheriff races put jail conditions and police misconduct under the microscope?

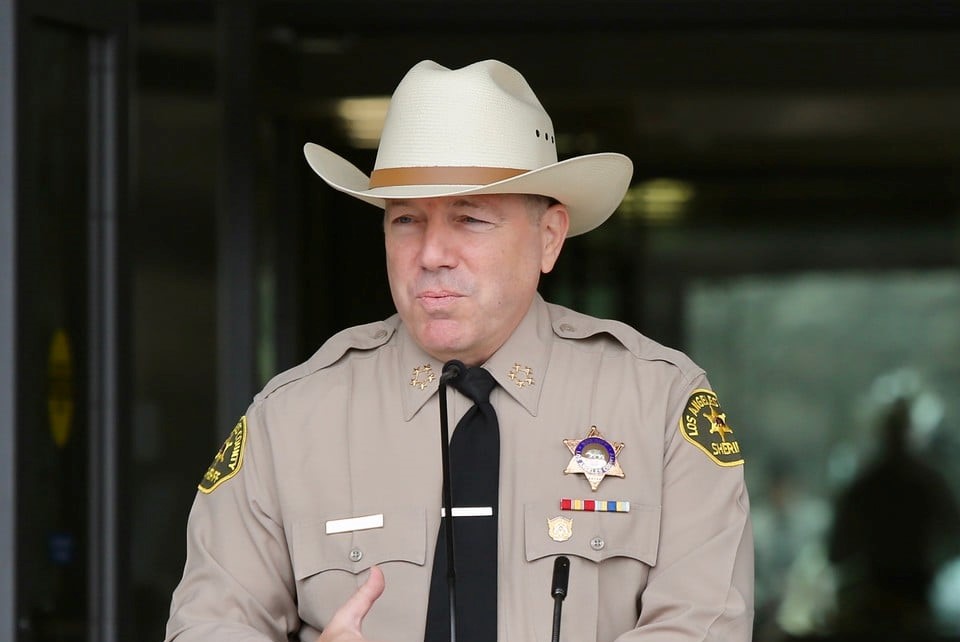

Los Angeles Sheriff Alex Villanueva is one of the country’s most vocal foes of criminal justice reform. Besides overseeing a department that frequently draws disturbing headlines about abuse by his deputies, Villanueva has defied efforts at civilian oversight, rehired deputies who were fired for misconducts, and put in place a secret police force to target his critics.

Villanueva’s re-election bid, perhaps the country’s most high-profile law enforcement race this year, has drawn a large number of contenders, though it remains to be seen how the grassroots activists who have fought the sheriff in recent years respond. Some of the other declared candidates are also mired in controversy.

Sheriff races provide an opening for the public to confront misconduct, dismal jail conditions, and the widespread use of practices like solitary confinement. This year, California will elect nearly all of its sheriffs, alongside other states that include Alabama, Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, North Carolina, and Wisconsin. This electoral calendar presents opportunities to assess the records of officials like Thomas Hodgson, the longtime GOP sheriff of Bristol County, Massachusetts. An ally of Donald Trump, Hodgson has faced statewide and federal probes, lawsuits, protests, and hunger strikes over deaths in the jail and over his treatment of people detained there.

It’s likely that many incumbents will coast to re-election unopposed, but hotspots of debate are already emerging. In Hennepin County (Minneapolis), the sheriff is retiring after a drunk-driving crash. In Alameda County (Oakland), a pair of reform candidates have formed a combined ticket for DA and sheriff, an unusually concerted effort to change local practices.

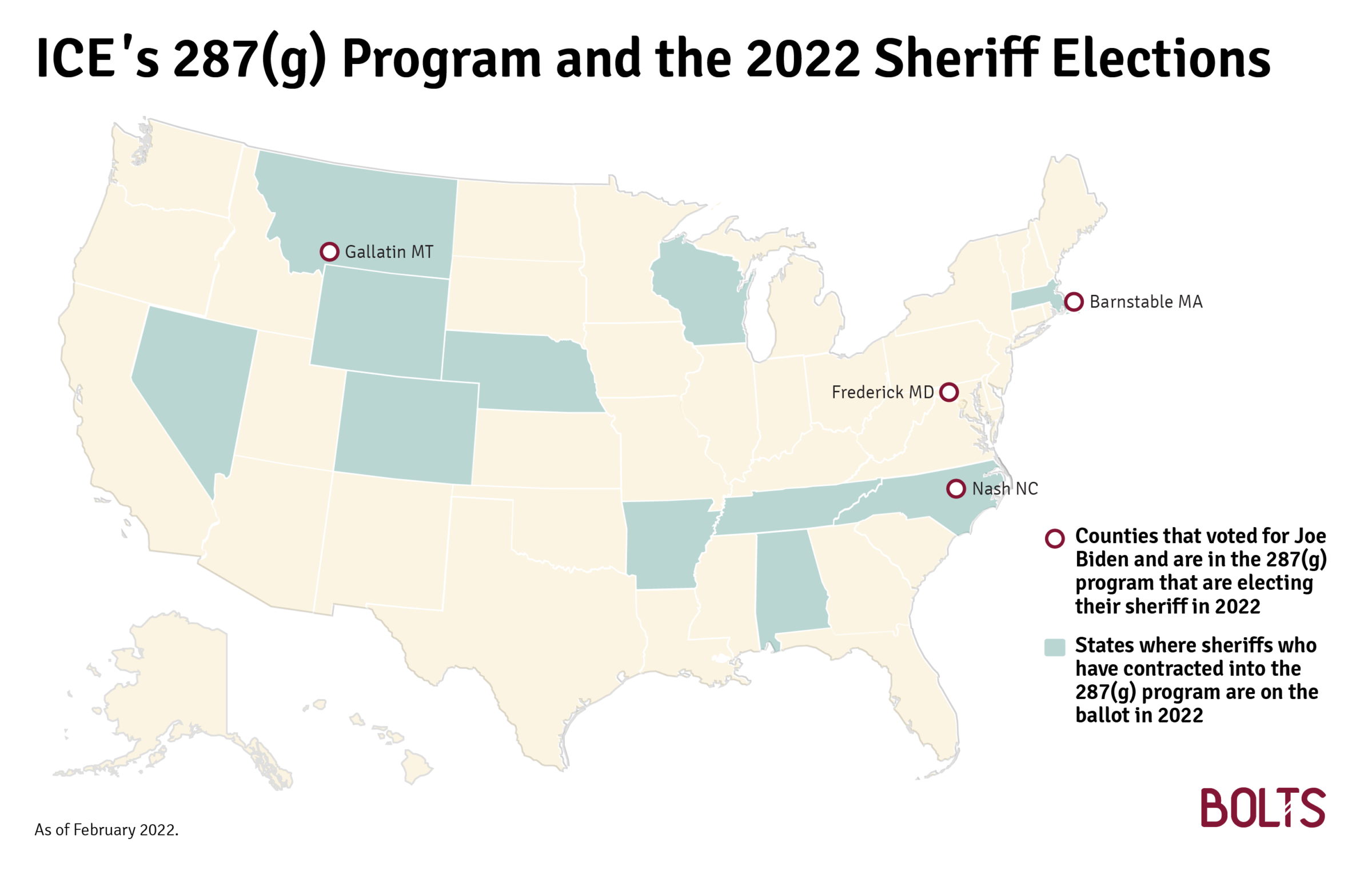

3. Can immigrant rights activists further constrain local cooperation with ICE?

Under President Donald Trump, immigrant rights activists had great success challenging sheriffs who helped federal immigration agents. Will that energy transfer to the first major election under Joe Biden? Concerned that the salience of this issue is fading under a Democratic president, activists have warned that local collaboration with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) continues to ensnare immigrants regardless of the change in administrations.

On this issue, North Carolina is the most obvious battleground this year. Many candidates who ran on breaking ties with ICE won there in 2018 and then promptly did so once in office. All are up in 2022. In populous Wake County (Raleigh), the old sheriff wants his job back: Republican Donnie Harrison is challenging incumbent Democratic Sheriff Gerald Baker. After he ousted Harrison in 2018, Baker ended Wake County’s participation in ICE’s so-called 287(g) program, which empowers sheriff’s deputies to act as immigration agents.

The 287(g) program could be an issue elsewhere this year. Of the counties that remain in it, 38 have sheriff elections this year.

While most of these counties are deeply conversative, a Bolts analysis shows that Joe Biden carried four of them in 2020: Frederick County, Maryland; Barnstable County, Massachusetts; Gallatin County, Montana; and Nash County, North Carolina.

4. Will organizing increase around judicial elections?

Judges are an increasingly visible frontline in the fight over mass incarceration. Still, learning much about judicial candidates in most places remains a herculean task, a major hurdle for the spread of local efforts to “flip the bench” by electing judges running on less carceral approaches.

Still, such campaigns have proved successful in an eclectic mix of jurisdictions in recent years, from New Orleans and Las Vegas in 2020 to Pittsburgh and Missoula in 2021. Hundreds more counties hold local judicial races this year. Reformers are the ones playing defense in Harris County (Houston), where voters elected a wave of new judges in 2018, paving the way for milestone local bail reforms. Many of those judges face a challenger as soon as the March 1 Democratic primary.

Dozens of supreme court elections also hold major ramifications for criminal justice. The partisan balance is in play in some states (e.g. North Carolina or Ohio), but the stakes transcend partisanship. In Washington State, progressives appointed by Governor Jay Inslee joined milestone rulings on drug policy and youth sentencing last year; two of them now face voters in 2022.

5. What new paths for reform will open in state-level governments?

Voters will settle roles in state governments that have major ramifications for criminal justice policy—whether by choosing governors (in 36 states), legislatures or attorneys general. In Maryland, for instance, the Republican governor who has pushed lawmakers to toughen sentencing laws and vetoed reforms cannot seek re-election due to term-limits. The governor’s race in Massachusetts hosts a crowded Democratic primary that has some candidates proposing bolder changes than others.

In Arizona, a state where promising reform bills have repeatedly derailed due to divides within the governing Republican Party, the GOP primaries will decide which side has the upper-hand for the upcoming session. In New York, Republicans tried to gain ground in the legislature in 2020 by spreading fear over state bail reforms, only to lose many seats; similar issues remain a major dividing line between gubernatorial and legislative candidates this year.

California may host one of the nation’s most notable attorney general races this year. Among the many challengers to the state’s progressive attorney general, newly appointed to the job last year, is the Sacramento County DA, who has frequently fought criminal justice reforms or championed their rollback.

Meanwhile in North Carolina, state judges have, at least for now, blocked new gerrymandered maps that would have given GOP lawmakers a strong shot at a veto-proof majority. Numerous Republican priorities, including forcing local sheriffs to collaborate with ICE, hang in the balance of what comes next.

6. Can serious reforms to policing gain traction in city halls?

Mayors have formed something of a barrier against major changes to policing, especially when it comes to the size of police budgets. 2021 reinforced that trend, as many candidates who ran on upending policing lost, with some notable exceptions. Michelle Wu won in Boston, for instance, by making the case that public safety calls for broadly boosting public services.

Voters in 2022 will choose new mayors in the second nation’s most populous city, Los Angeles, as well as in Austin. Those are both municipalities where policies criminalizing homeless people are a major issue. In Washington, D.C., policing is already a major fault line in the race between Mayor Muriel Bowser, who recently called for buttressing police funding, and City Council Member Robert White, who has championed reforms that have put him at odds with the police.

7. With ballot initiatives, how will voters take matters into their own hands?

Politicians remain squishy on drug policy, even when there is evidence that reforms would be popular, so advocates are again pursuing the referendum route. Initiatives to legalize recreational or medical marijuana may end up on the ballot this year in Arkansas, Maryland, Missouri, North Dakota, and Oklahoma, among other states. California, Colorado, and Michigan may weigh in on legalizing psychedelics. And activists in Washington are hoping to collect enough signatures for an initiative to decriminalize drug possession, two years after Oregonians approved a landmark referendum doing just that.

Other criminal justice policies will likely end up on the ballot as well. Some California reformers hope to repeal the state’s three-strikes law, for instance, while a law firm is proposing an initiative to toughen sentencing for retail theft (voters easily rejected a similar measure in 2020). Municipal initiatives are also on the table in cities with an unfriendly statewide politics; voters in Austin, for instance, will decide whether to decriminalize marijuana and ban no-knock warrants in May.

8. How many elections dead end just because no one runs?

Important local elections are routinely uncontested, at times due to shady maneuvering. In some states, controversial barriers to eligibility will be a limiting factor this year, starting with California’s sheriff races.

The filing deadline in most states is still weeks or months away, but if Texas is any indication, uncontested races remain as big an impediment to democratic accountability as ever: only 12 of the 50 DA elections in the state this year drew more than one candidate by the December deadline. In 38 of those 50 counties, prosecutors will waltz into office uncontested, including incumbents in large counties like Collin, Denton and Fort Bend—growing suburban counties, two of which are more populous than Boudin’s jurisdiction of San Francisco, but where the earliest possible election debate over the shape of punishment is now 2026.

This pattern extends to some of the most visibly powerful institutions in the land. Between 2012 and 2018, Georgia held 12 uncontested elections for its state Supreme Court. That remarkable streak was finally broken in 2020, though the four candidates who ran for its two seats all had conservative credentials. With four of Georgia’s nine Supreme Court seats on the ballot this year, the state’s March filing deadline will likely be as decisive as the May election.