North Texas Conservatives Police High Turnout and Close Races as “Anomalies” Suggesting Fraud

Election deniers nationwide are twisting civic engagement and results they don’t like into evidence of rigged elections.

| July 29, 2022

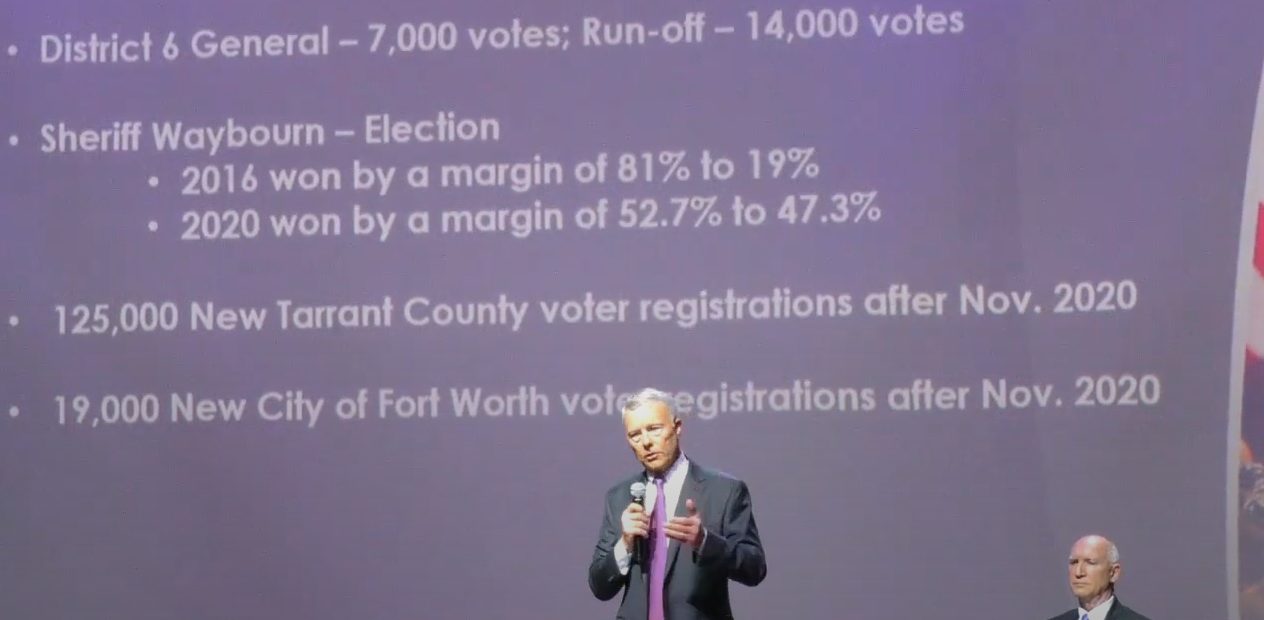

As his surname might suggest, Fort Worth attorney Bill Fearer played an alarmist emcee for the late January gathering of election deniers hosted by the conservative group Tarrant County Citizens for Election Integrity. Before introducing a parade of speakers spreading baseless conspiracies about fraud in elections ranging from Donald Trump’s 2020 loss to local races, Fearer had some startling figures of his own that he wanted to show the crowd—“anomalies,” he said, “that certainly don’t prove anything, but they raised our concerns.”

On the list of bullet points Fearer splashed on a big screen behind him was the name of Tarrant County Sheriff Bill Waybourn, a tough-talking cop who first won in 2016 with an overwhelming 81 percent of the vote but only narrowly prevailed when he went up for re-election in 2020. To Fearer, that slide is enough to suggest fraud. “There was no glaring issue with the job that he (Waybourn) had done that we could perceive, yet in 2020 the margin was only 5 percent,” Fearer said.

That remark would shock Waybourn’s local critics, who have organized against the scandal-plagued sheriff and his policies for years. They have protested the dehumanizing and dangerous conditions that pervade inside the jail he oversees, which has seen a spike in deaths since he took office.

While Waybourn has become a fixture of right-wing media and a reliable dial-a-quote for comments demonizing migrants, protesters, and leftists, his rhetoric and numerous alarming incidents on his watch—including a pregnant woman with mental illness giving birth alone while locked inside her cell in 2020—have galvanized a coalition of local activists who have demanded his resignation and supported his Democratic opponent in 2020. The group has continued to organize against the sheriff and his policies under the name “New Sheriff Now Tarrant County,” testifying in front of the county commission to demand justice for people harmed in Waybourn’s jail, including a woman with mental disabilities who recently left the lockup bruised and in a coma.

But Fearer’s slideshow to the Tarrant County group drew on rhetoric that has spread among conservatives, pointing to bare election results they dislike as reason enough for suspicion. Rather than providing documentation that justifies those doubts, they treat outcomes that deviate from their expectations—including Trump’s loss, Waybourn’s close call, and even signs of increased civic engagement, like recent record-high turnout—as signs of fraud.

The conspiracies often carry a racist tinge, from Trump’s lies that widespread illegal voting by immigrants cost him the popular vote in 2016 to claims made by Roy Moore, the losing 2017 Republican nominee in Alabama’s U.S. Senate race who was accused of molesting teenagers. Moore pointed to “anomalous” high turnout in the state’s Black communities as evidence of fraud when he refused to accept defeat and sued to block his opponent’s certification. His lawsuit called it “inexplicable” that Jefferson County, home to Birmingham, would have a higher turnout rate than the rest of the state. In 2020, Trump supporters similarly twisted high turnout into a sign of fraud, and Trump pointed to President Joe Biden’s large majorities in predominantly Black cities and counties as reason to doubt the results.

Fearer and his Tarrant County group, which deny Trump’s 2020 loss, have employed the tactic to spread doubt about local election results in recent years. The group argues without evidence that the record high turnout in Fort Worth’s hotly contested mayoral race last year could indicate fraud. (The Republican candidate prevailed in that race.)

Following the election, the group began mailing out postcards asking residents to “verify” their votes by entering personal information into a non-secure website, spooking state and local election officials, who urged voters not to respond. Last week, Votebeat and the Texas Tribune reported that organizers with Tarrant County Citizens for Election Integrity are physically combing through about 300,000 ballots cast during the county’s 2020 GOP primary elections in search of irregularities.

And the group has moved to police the vote in other ways. In his January presentation, Fearer displayed a series of photos that he said showed vacant lots and dilapidated properties where people were registered; Fearer also included many places that poor and vulnerable people might be staying like halfway houses, rehab centers, shelters, budget motels and RV parks on his list of “potentially fraudulent addresses.” Fearer, who did not respond to multiple efforts to contact him for this story, said during his presentation that the group is also organizing with activists monitoring elections in other Texas counties and across the country.

The organizing by North Texas election deniers is part of a larger attempt by some conservatives to police elections across the state. Bolts reported in April on a group of stop-the-steal activists who are raising money for private investigators to search for voter fraud in the Houston area—and whose actions have already led to the armed assault of an innocent truck driver wrongly accused of fraud. In Texas, these activists have benefited from the support of state Attorney General Ken Paxton, who aided in the legal efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential race.

This suspicion about election results has also inspired new restrictions and threats against people who engage in the electoral process. Republicans across the country in recent years have used the specter of widespread fraud to pass laws establishing new barriers to voting while further criminalizing the elections process; 26 states have enacted, expanded, or increased the severity of 120 election-related criminal penalties since the 2020 election, according to a recent analysis by States Newsroom of data compiled by Voting Rights Lab . States like Florida and Tennessee have also ramped up their policing of elections this year.

The North Texas group’s conspiracy theories also extend to Tarrant County Election Administrator Heider Garcia, who was appointed to the post by a bipartisan county election commission in 2018. In April, they posted a video attacking Garcia that focused on his Venezuelan heritage and accused him of eroding the security of local elections. Two weeks later, at a county commission meeting, Garcia delivered a lengthy presentation running the public through every step of the voting and counting systems and explaining the various processes involved to ensure security; he even included sped-up surveillance footage of voting machines sitting in a room overnight, free from tampering after an election.

The meeting was packed with residents, many of whom applauded Garcia and later testified to express confidence in the county’s election systems. But when Fearer testified, he urged county officials to consult with Tina Peters, an election-denying county clerk in Colorado.

The group has also hosted virtual forums with Peters, who was criminally indicted this year on charges that she tampered with voting equipment in an effort to boost Trump’s bogus claims of a stolen election; Fearer’s group hails Peters as an expert and hero. Peters handily lost her bid to become Colorado’s secretary of state last month, but refused to concede and promptly claimed the results were false. “We didn’t lose,” she said on election night. “We just found more fraud.”