As Michigan Raises the Age, Advocates Vow to Press for More Change

Michigan automatically treats all 17-year olds as adults, but that will soon change with a major new reform. But prosecutors will retain broad discretion.

| November 14, 2019

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

A major new law will put an end to the automatic treatment of all 17-year olds as adults. But state prosecutors will retain “ridiculously broad” discretion.

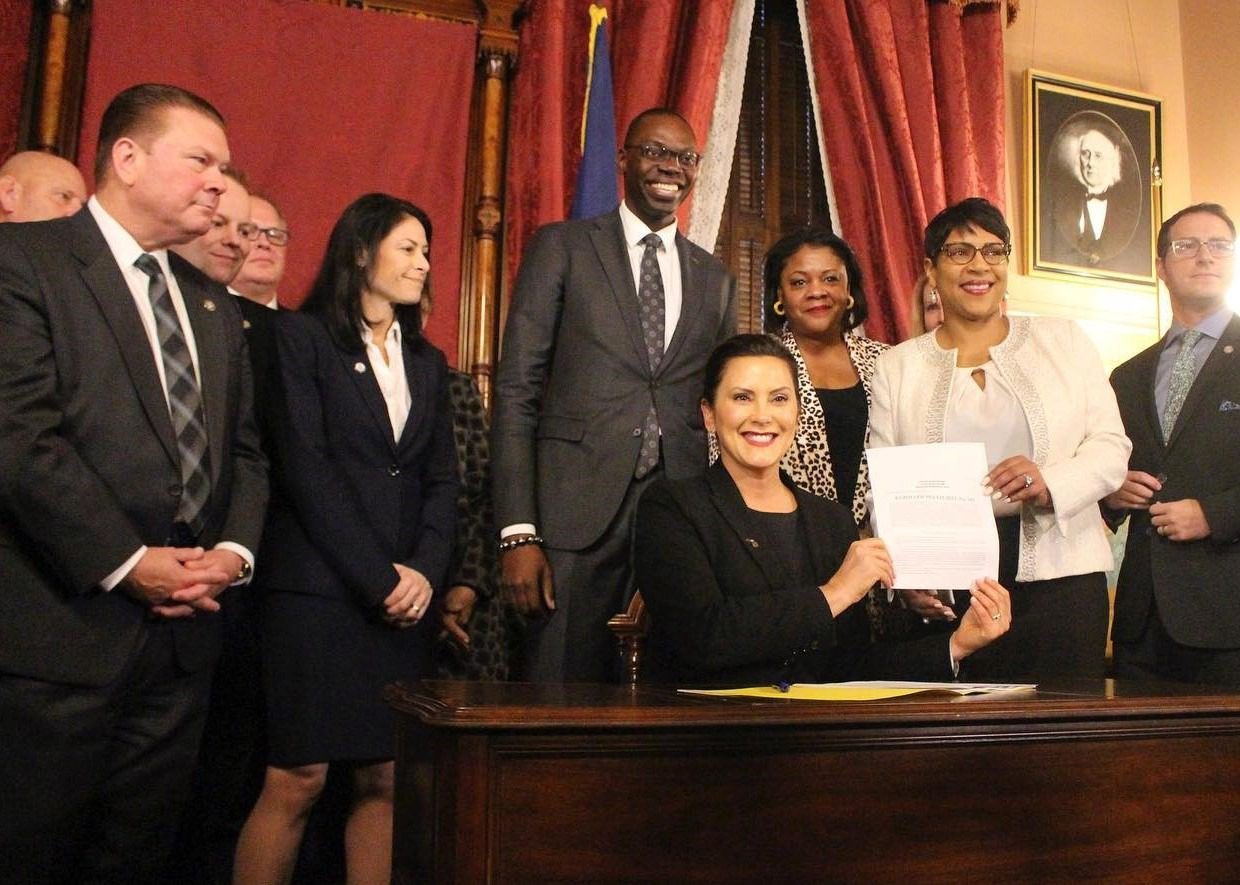

Michigan automatically treats all 17-year olds as adults, which throws thousands of minors into adult court. But that will soon change: A package of bills, adopted by the Republican legislature and signed into law by Democratic Governor Gretchen Whitmer in October, will raise the age until which teenagers can be in the youth system by one year, to 18.

“Our state no longer lags behind the rest of the nation in how we treat 17-year-olds who become involved with the justice system,” Jason Smith, who pushed for this reform as director of youth justice policy for the Michigan Council on Crime and Delinquency (MCCD), told the Appeal: Political Report. “It was a long road to get here, but the advocates, grassroots supporters and other stakeholders should feel proud of what we were able to accomplish.”

The youth system has a comparatively rehabilitative outlook, more alternatives to incarceration, and stronger confidentiality rules that also help minors avoid a permanent record. “The juvenile court system is far from perfect, but in comparison to the adult system, it is still light years ahead,” Marcy Mistrett, CEO of the Campaign for Youth Justice, a national organization, told the Political Report.

The reform doesn’t go into effect until 2021, though. Even then, prosecutors will retain broad discretion to charge minors much younger than 17 as adults with little oversight, and state and national advocates like Smith and Mistrett vow to press ahead with further demands.

—

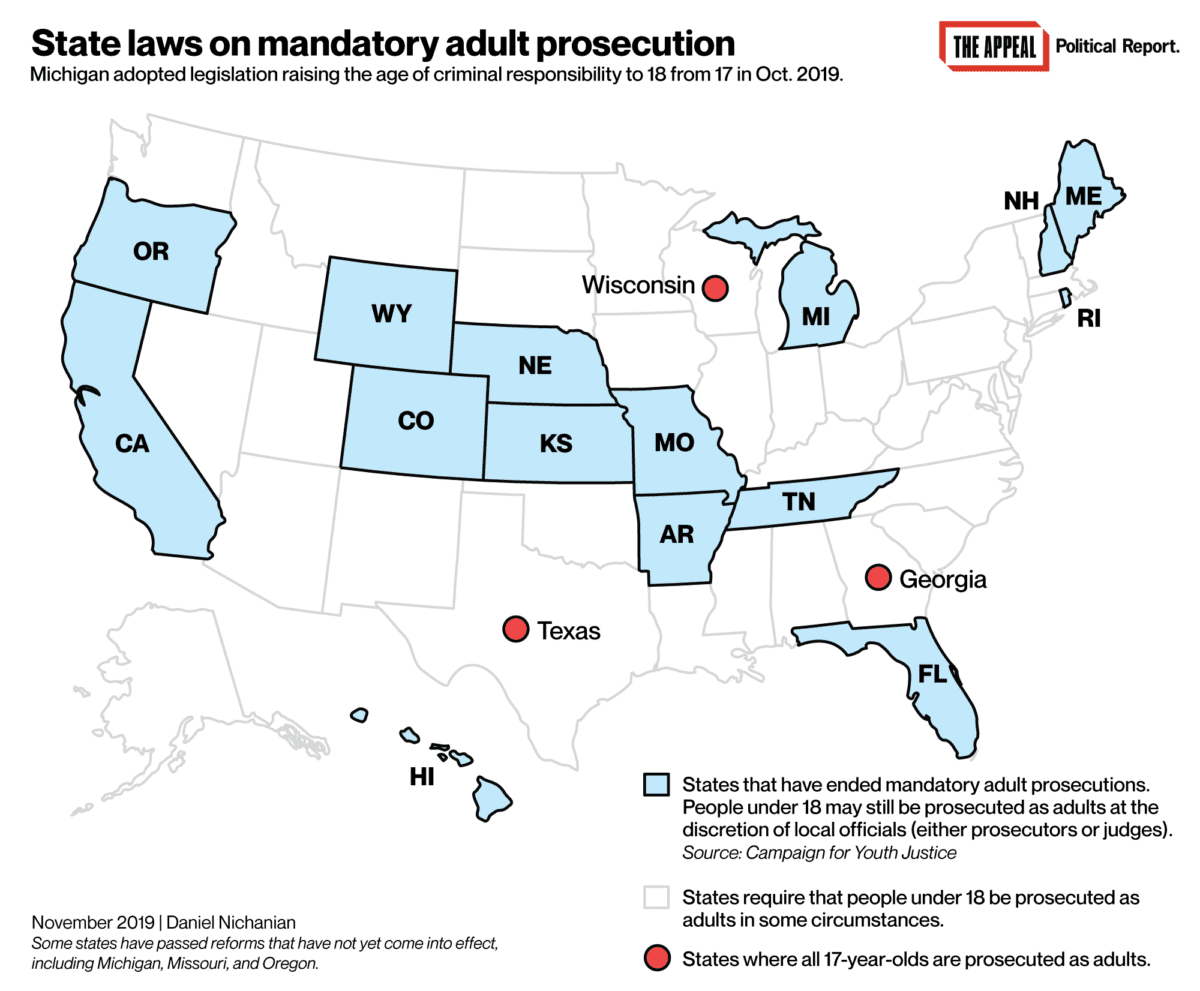

Since 2010 alone, 10 states have passed laws raising the age of criminal responsibility to 18. These reforms have significantly expanded the youth system’s purview.

According to the Campaign for Youth Justice, 137,000 people under 18 were automatically excluded from the youth justice system because of their age in 2010. Mistrett estimated that this number will drop to just 25,000 once all the “Raise the Age” laws passed in recent years (including Michigan’s) become effective.

“Since the juvenile courts established themselves as independent from adult courts in the turn of the 20th century, this is the closest we’ve come to having a universal agreement that 18 should be the minimum age at which children should be criminally responsible,” Mistrett said.

Only three states have passed no law raising the age to 18: Georgia, Texas, and Wisconsin.

Michigan’s reform brings an added milestone. Whereas many states require that minors charged with certain severe offenses be treated as adults, Michigan has no statute providing for mandatory or automatic adult prosecution. And no such statute was added into this package. Therefore, come 2021, no Michigander under 18 will be automatically excluded from the youth justice system, whether because of age (as will soon only be the case in three states) or to another factor (as is the case in many more).

Michigan will still enable minors to be prosecuted as adults, however. It just won’t require it.

In fact, state prosecutors enjoy wide discretion when it comes to charging children at least age 14 as adults, with no judicial oversight. (This unsupervised authority is known as “direct file.”) Prosecutors can do this if they are using a specified range of charges, but once they choose to file adult charges against a minor (a decision typically made shortly after an arrest), that minor is effectively locked into that system. Prosecutors can also seek judicial waivers to prosecute more minors as adults.

Michigan prosecutors have “ridiculously broad” powers, Mistrett said. “Michigan is one of the only jurisdictions that has no safety net. The prosecutor can determine in a very broad swath of cases which court they decide to charge children in, and if the child pleas to anything less than that, or is found guilty of anything less than that, there is still not a way that children can be adjudicated as a juvenile.”

Still, based on past patterns Mistrett expects that no more than 12 percent of the 17-year olds arrested and charged once the new laws becomes effective will be prosecuted in adult court. That would considerably shrink adult prosecutions; she called this reform “monumentally important.”

Michigan prosecutors’ vast powers to treat minors as adults is just one of the issues that criminal justice reform advocates are raising in the wake of the state’s new reforms. What may be next for youth justice in Michigan and for “Raise the Age” nationally?

—

Various paths to shrink discretionary adult prosecution: Reforms adopted in other states point to strategies that would counter the adult prosecutions of minors in Michigan. Most straightforwardly, Michigan could fully forbid treating youth as adults; no state has done this up to age 18, but last year California barred anyone under 16 from being prosecuted in adult court.

Short of that step, Michigan could end prosecutors’ “direct file” prerogative to send minors to adult court; Oregon adopted a law in July to ensure judicial oversight. Moreover, Indiana in 2016 and California last month adopted laws to enable some minors prosecuted in adult court to be transferred back into the youth system if found guilty on different charges than the ones for which they were originally treated as adults; Michigan lacks such a return pathway.

Where will youth be detained? The Senate’s version of Michigan’s Raise the Age reforms contained a provision that was stripped out of the final version: It would have required that minors under 18 not be incarcerated in adult facilities even when they are convicted in adult court. Michigan youth detained in adult prisons have suffered cruel treatment, as a 2015 HuffPost investigation documented. Smith, of MCCD, told the Political Report that fighting for this will be a priority for his organization. “We believe that it is in the state’s best interest to remove all youth from adult facilities,” he said.

Many youth are detained in Michigan over status offenses: A higher-than-average share of the state’s confined youth are detained for noncriminal acts such as running away or skipping school, which are known as status offenses. “The fact that a child can go into detention for something that isn’t a crime is state-sanctioned trauma,” Washington State Senator Jeannie Darneille told The Appeal this year. Washington addressed that in May, when it passed a law eliminating detention as a sanction for truancy and for at risk youth. Can Michigan follow suit?

Michigan made it 47. What about the final three? Bills raising the age to 18 were introduced this year in each of Georgia, Texas, and Wisconsin, the three states that are set to keep treating all 17-year-olds as adults. But these legislatures adjourned without taking action. In Wisconsin, the Democratic governor proposed this reform, only to be ignored by the GOP legislature; in Georgia, it was introduced by GOP lawmaker Mandi Ballinger but not taken up by her party’s leadership.

Of the three states, it’s Texas that has come closest in the past. The House has repeatedly passed such a reform, only to see it die in the Senate. One reason is Senator John Whitmire, who is the chairperson of the Committee on Criminal Justice. Whitmire, a Democrat, is a consistent critic of “Raise the Age” proposals and of other youth justice reforms. “I think at 17 you should know right from wrong,” he said in 2015. The House passed no bill this year, though, despite holding a hearing; multiple state advocates told me that they were confident this was only because House members did not expect the Senate to take it up.

Why only 18? Some advocates are pressing states to recognize that being a day over 18 should not cut off access to the youth justice system’s comparatively rehabilitative outlook. They also point to research in neurobiology and psychology that finds that people’s brains develop into at least their mid-20s. In 2016, Vermont passed a law raising the age to 21. Lawmakers have filed similar proposals in Connecticut and Massachusetts, with the support of some prosecutors like Boston’s Rachael Rollins. Could these states, or others, join Vermont next year?

Visit the Political Report’s interactive tool on legislative developments on criminal justice reform for more coverage of youth justice legislation.