A New Cycle of Texas Gerrymandering: Your Questions Answered

A redistricting expert answers questions from Bolts readers about the effort to redraw Texas’ congressional map, and its effects on communities of color and political representation.

| July 31, 2025

The Texas legislature began meeting in a special session last week to adopt a new congressional map that will, they hope, provide additional seats to the GOP in next year’s midterms.

On Wednesday, Republicans released a draft map that could shift as many as five districts their way; the map, if it came to pass as is, would force multiple Democratic members of Congress into red-leaning districts, and pit two Austin Democrats against one another.

The state last redrew its voting maps in 2021, and redistricting again after just five years is rare by national standards. A new gerrymander could help the GOP keep control of Congress, and it could drastically reshuffle local power, including by further diluting the votes of Texans of color.

We asked readers to send us their questions about Texas redistricting as part of our series “Ask Bolts.” And we invited Michael Li, an expert on redistricting, to respond to some of your questions. Li has closely followed years of controversies and litigation over gerrymandering in Texas as senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice.

He answers nine reader-submitted questions, below. You can navigate to the question that most interests you here, or scroll down to explore them all:

Has Texas ever tried mid-decade redistricting before?

Can every state redistrict in this way?

How is this process affecting voters of color?

Are courts still positioned to regulate this redistricting?

What data is Texas using to inform its new map?

How much do GOP incumbent demands matter here?

Could legislators toy with the count of people who cannot vote in the new maps?

Could this gerrymander backfire for Texas Republicans?

What could fair redistricting look like?

If Texas had to draw a map under strong anti-gerrymandering protections, Li shared yesterday, the map would have roughly 17 to 18 Democratic seats out of Texas’ 38 seats, compared to the 13 seats Democrats currently hold, and the meager 8 they may hold under the new GOP map. But how do these maps create that discrepancy, are there options to restrict gerrymandering, and do Republicans face risks in trying to predict next year’s outcomes? Keep reading to learn more about redistricting in Texas.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Historically, has a Texas governor ever called a special session for mid-decade redistricting? If so, what was the outcome? —Anonymous, from Texas

Texas has had to redraw its congressional maps virtually every decade since the 1970s because a court ordered a redraw after finding that the map discriminated against Black or Latino voters or both. But only once, in 2003, has it undertaken the process voluntarily in a special session.

The 2003 redraw took place after Republicans won control of the Texas House in the 2002 midterms, giving them control of both the Texas legislature and the Governor’s Mansion for the first time since Reconstruction. Then-Governor Rick Perry called a special session to replace the court-drawn congressional map the state had been using, with the aim, then as now, of maximizing Republican advantage. And in the subsequent 2004 elections, four Democratic incumbents, all white, lost their seats. (Another white Democrat switched parties to save his seat.)

But while the 2003 redraw is now mostly remembered as a brazen Republican power grab, it’s worth pointing out one big difference from the current mid-decade redistricting.

In 2003, the map that Republicans wanted to replace was drawn by a federal court after the legislative process deadlocked. That map largely left in place the highly gerrymandered 1991 congressional map drawn by Democrats, which The Almanac of American Politics called “the shrewdest gerrymander of the 1990s.”

By 2002, Republicans in Texas were handily winning statewide elections, but Democrats under the court’s map still won a narrow majority of congressional seats.

Contrast that with today: Under the current Texas congressional map, Republicans already win 25 of 38 congressional districts—two-thirds of seats.

That’s a sizable advantage in a state where Republicans don’t get nearly that share of the vote—Ted Cruz running for re-election in 2025 got just barely 53 percent of the vote. And none of the GOP seats were competitive in 2024.

But now, despite having gotten a map that works pretty darn well for them, Republicans’ plan seems to be to try to squeeze five more GOP seats out of Texas. That would give Republicans an astonishing 80 percent of Texas’s congressional delegation. By the very rationale that Republicans used in 2003 to redraw the map, its Democrats who are unfairly under-represented.

Can every state continually rejigger district lines to shift power in Congress or state legislatures? — @Betsy_Cazden on X

No. While there is no federal limit on how many times a state can redistrict, some states have express provisions in their state constitutions that only allow maps to be redrawn once a decade—an exception being made if there is a court order to do so. Likewise, state courts in some states have ruled that redistricting is a once-a-decade affair.

But in many states, the situation is ambiguous and an issue of first impression.

That’s because typically lawmakers tend to treat redistricting as akin to getting a root canal or colonoscopy. Maybe you have to have one, but it’s definitely not something you seek out. So mid-decade redistricting hasn’t happened a lot outside of court orders, and there is a lot of untested ground about what states can and can’t do voluntarily. We may be about to find out. [Editor’s note: Since Abbott’s decision to call this special election, stories have popped up floating possible mid-decade redistricting in many states, including California, Florida, Missouri, New York.]

I keep seeing that Republicans will target seats that Black or Latino politicians are holding right now. What should we be watching in the maps to see if they violate protections for people of color? —Joan, from California

If Republicans are serious about netting five more seats out of Texas, it’s going to be impossible to avoid targeting the political power of communities of color who, according to new Census Bureau population estimates, are now responsible for providing all of the state’s population growth.

That’s because of the 13 congressional seats that Democrats hold in Texas, only one—the 37th District in Austin—is majority white. All the others are majority non-white by eligible voter population, and 10 of 12 of those elected a Black or Latino member in 2024.

While we wait to see what the final map will be (Republicans have released an initial proposal but that map could yet change), some of the districts people are watching most closely include the 33rd District in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex and the 9th, 18th, and 29th Districts in the Houston region.

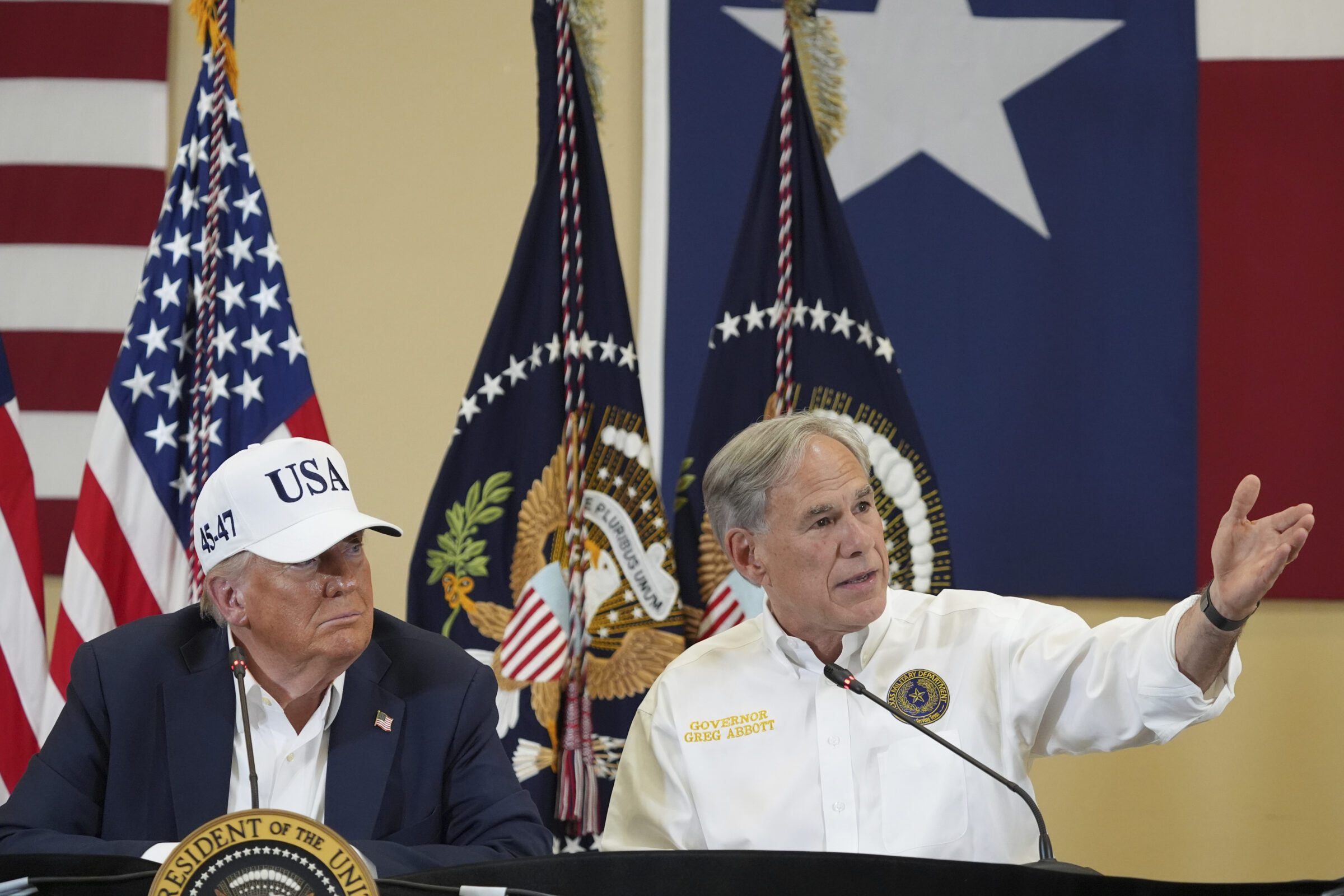

Those districts were named in a letter sent on July 7 by U.S. Assistant Attorney General Harmeet Dhillon to Governor Greg Abbott raising racial gerrymandering concerns: Dhillon’s contention was that race “predominated” in the design of the four districts, and that this was illegal. Governor Abbott then cited the letter when adding congressional redistricting to the special session call.

An important note: While the Dhillon letter is the ostensible basis for the current mid-decade redistricting, it’s a pretty flimsy basis for launching a map redraw.

Let’s start with the letter’s claim that the four districts are racial gerrymanders. Dhillon’s contention is inconsistent with the state’s repeated position during the 2021 redistricting process and subsequent litigation that the map was drawn on a “race blind” basis. In fact, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton reiterated that position in his July 11 response to Dhillon, saying that lawmakers “drew the Texas districts blind to race” and had merely “sought to maximize Republican political advantage balanced against traditional redistricting criteria.” If that’s the case, there’s absolutely no need for Texas to redraw the four districts.

The Dhillon letter also is legally perplexing.

In 2024, the Fifth Circuit ruled that the Voting Rights Act does not let multiple minority groups, say Black and Latino voters, join together to bring a claim to compel creation of a district where minority voters are a majority. This type of district is often called a “coalition district” because the district’s minority voters, voting together as a coalition, can elect a candidate that they jointly prefer even if the district’s white voters strongly prefer a different candidate.

But while the law in the Fifth Circuit (where Texas is located) now is that you can’t compel creation of coalition districts, Dhillon’s letter seems to go further by suggesting that any district that has a majority non-white population, even if it was not intentionally created to be majority non-white, is unconstitutional or at least constitutionally suspect.

Multiple legal experts have testified that this understanding—if that’s what the somewhat ambiguously written letter actually meant to convey—is simply not the law. In fact, dismantling [these districts], in the absence of a legal reason for doing so, starts to look a lot like intentional racial discrimination.

Is there a third party ensuring this is fair and not designed to discriminate against people of color?—Anonymous, from Texas | Assuming this will be challenged in the courts, what is the assessment of a lawsuit’s chances of success in opposing it? —@nikolayevichlev on BlueSky

These days people are often skeptical about federal courts, and not without some reason. But I want to put this in headlights: The Voting Rights Act is still the law of the land.

The Supreme Court may have weakened the Voting Rights Act over the years, but it was just two years ago that the justices ordered Alabama to create a new Black congressional district. Likewise, around the country, voters of color continue to successfully use the VRA to combat racially discriminatory line drawing at all levels of government. Further attacks on the VRA may yet come, maybe even in the Supreme Court term that starts this October. But don’t count the courts out yet.

In particular, in the case of the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex and Greater Houston, you are talking about regions where there are significant Voting Rights Act liabilities. In both areas, there are strong claims in pending litigation that there need to be more minority districts than the 2021 map has. At first glance, this latest map proposal doesn’t seem to do anything to address that deficit.

And the risk doesn’t just come from the VRA, Texas also could trigger a finding of intentional discrimination.

For an example of what could happen, just look at the last decade. After the 2010 census, Texas Republicans so aggressively drew the state’s congressional map along racial lines that a three-judge panel in Washington found not only that the state had discriminated against Black and Latino voters, but that map challengers had “provided more evidence of discriminatory intent than we have room, or need, to discuss.”

A similar finding this decade could land Texas back under preclearance using the “bail-in” provisions of Section 3 of the Voting Rights Act. Bail-in requests are already pending in litigation over Texas’s current congressional and legislative maps. They could become even stronger if some of these changes come to fruition.

In short, Texas Republicans seem ready to pick a very risky, high stakes Texas-sized legal fight.

Will the Texas legislature use the population figures from the 2020 census, or will they use updated information to ensure districts have equal populations? — Ben C., from Texas

Population equality is just one of the relevant legal requirements: Since the 1960s, the Supreme Court has interpreted the Constitution as requiring near-perfect population equality in congressional redistricting. And the data that states around the country use for getting to strict population equality comes from the once-a-decade census. Nothing else is precise enough to meet the near zero-deviation requirement for congressional districts.

While there are alternative data sources, like the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS), that are updated more often, these don’t attempt to count everyone. Instead, the ACS and other similar surveys are estimates based on a representative sample. These alternative sources do not meet the Constitution’s demand for zero-deviation accuracy.

So, that means that even though the 2020 census is now five years in the past, that’s what map drawers will use—at least for population equality purposes.

But that doesn’t mean data from more recent sources is irrelevant. Texas is growing explosively, and information that, for example, some rural areas in 2020 are now fast-growing suburban communities can be relevant to arguing what communities should be kept together as lines are redrawn.

Likewise, different data sources play a big role when it comes to complying with other legal requirements. For Voting Rights Act compliance, for instance, it is typical to look at citizen voting age population estimates, which are released annually by the Census Bureau through the American Community Survey. This more recent data, for example, might show that a Voting Rights Act claim that wasn’t viable in 2020 is now much stronger.

How much will GOP incumbent demands matter for the new map? Which ones will be the hardest for the GOP to implement in a maximal gerrymander? — Magenta, from New Jersey

Incumbent desires traditionally get a lot of attention in Texas, and lawmakers (or more specifically, their staffs) usually are very solicitous, at least when it comes to incumbents of their own party.

In the 2011 round of redistricting, for example, one San Antonio-area Republican congressman wanted the San Antonio Country Club added to his district, and bingo, there it was. In North Texas, another GOP congressman wanted the elite girls prep school his granddaughters attended in his district, and lo and behold, an email later, it was added. (By contrast, a Black Democrat, Eddie Bernice Johnson, tried and failed to get lawmakers to make even the small change of putting her district office back in her district.)

Of course, everybody is looking out for his or her electoral prospects, not only in the general election but also the primary since in many places, it’s the primary that is more important than the general in determining who goes to Washington.

But it remains to be seen how much those demands matter this time around. To do a gerrymander this aggressive, a lot of Republican incumbents are going to end up having Democratic voters from nearby or maybe even far-flung districts added to their districts and vice versa. Moreover, even if a district remains comfortably Republican, a GOP incumbent could find himself or herself with a very different set of Republican voters than the ones he or she has today—potentially setting up some interesting future primary challenges.

Could legislators try to toy with the count of youth, incarcerated, noncitizen populations—people who cannot vote—as a mechanism to “game the system”? To what degree is this type of data about nonvoters used in the gerrymandering process? —Sammy

There will be some of this, but probably not in a new way.

When equalizing congressional district populations, states equalize the total number of people in a district. It doesn’t matter whether you can vote or not: children, adult non-citizens, etc. Everybody counts.

Some people don’t vote because they are too young, some because they aren’t citizens. But Texas, which perennially ranks near dead last among states for voter turnout, also has a lot of people who are eligible to cast a ballot but, for one reason or another, don’t. In the 2024 election, for example, 8.7 million people were eligible to vote in Texas in 2024 but didn’t. By contrast, only 6.4 million people in Texas voted for President Trump and only 4.8 million for Vice President Harris.

And not surprisingly, if you are at all familiar with Texas, there is a huge racial component to who votes and who doesn’t. As some of my Brennan Center colleagues have found, states like Texas have yawning—and growing—racial turnout gaps. The turnout gap between white and Latino voters is particularly large in Texas.

All this is a long way of saying that map drawers, if they are nefariously inclined, have lots of opportunities to draw districts with large numbers of non- or unlikely voters—what some people in the redistricting space call “filler people.” And there appear to be places in the newly proposed map where that seems like it might be happening.

I’ve read suggestions online that the Texas GOP’s gerrymander could backfire and end up helping Democrats down the line. Is that really plausible and what might that look like? —Jordan, from Michigan | I’d like to hear about the possibility of this backfiring politically: I’m not sure how carefully they can draw the lines and assume stable voting patterns in such a volatile political climate. —Bethany A., from Texas

Yes, it is plausible, Texas is a very hard state to do a seat-maximizing gerrymander in. In fact, when Republicans drew the current Texas congressional map in 2021, they went the opposite direction and chose to draw the map defensively to “circle the wagons” and to protect incumbents come hell or high water. In other words, they had a choice: more seats or safer seats, and they opted for the latter.

The map that they got—Texas’s current congressional map—has been an absolutely superb one for Republican incumbents. Republicans win two-thirds of Texas’s congressional seats and win them by double-digit margins. In 2024, the closest race in a congressional district that a Republican won was by a margin of 14-points. Most Republicans win by 20 or 30 points, or more.

That’s night and day with the map from the decade before. When Republicans drew the prior decade’s map, they went all out to try to maximize seats. That included infamously dividing the City of Austin among six different congressional districts. It also included fracturing minority communities in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex and using clever tricks to weaken majority Latino districts elsewhere. It looked like a solid Republican map but it turned out to be a disaster.

That’s because doing a seat-maximizing gerrymander depends on one very important thing: the ability to predict the politics of the future.

In many parts of the country, that’s a very easy and safe bet to make. Not Texas. The Texas of the 2010s grew and diversified so rapidly, and shifted politically so fast, that by the end of the decade, districts that had reliably produced comfortable, if single-digit, wins for Republicans were some of the most competitive districts in the country. Republicans lost suburban districts in Dallas and Houston and came close to losing five or six more across the state.

Republicans avoided that problem this decade with a more conservative gerrymander. By redrawing the map so they go from winning two-thirds of seats to winning 80 percent, they could be setting themselves up for a repeat of the last decade.

Certainly, some of the districts on the newly released proposed map have margins that it wouldn’t take too much of a shift to put in play. And as last decade teaches, there could be additional surprises lurking in the wings in a state as explosively growing and changing as Texas.

Would there be a way to redistrict in a truly non partisan way? —Bolts Lover, from Virginia

Back in the 1980s and 1990s, when Democrats seemed like they would continue to be the majority party in Texas well into the future, it was Texas Republicans who urged creation of an independent redistricting commission and Democrats who vigorously opposed.

Then, in what seemed like a flash in the pan, the parties’ fortunes flipped. Texas Democrats became the ones who suddenly saw the value of a fair redistricting process and Republicans, with very few exceptions, became opponents.

I tell this story to stress how hard it is to get to a better, less manipulation-prone map-drawing process when in states like Texas, voters can’t use ballot initiatives to put reforms directly on the ballot. There are many reforms that have been proven to produce better redistricting outcomes. But the reality is that right now, we have an unlevel playing field that is very problematic.

In recent years, state courts have been a promising avenue for fighting gerrymandering, but here, too, progress is uneven. Some states have courts that have been willing to step into the proverbial “political thicket,” and others have pointedly decided to stay out.

To tackle congressional gerrymandering, there ultimately must be a nationwide answer. The Supreme Court told us in 2019 that the answer won’t lie in federal courts. But it could lie in Congress, which has the power under the Elections Clause to set the “Times, Places, and Manner” of federal elections, including what kind of districts are used.

Congress has used this power sparingly but it has imposed requirements that states use single-member districts and also once required that districts be compact, contiguous, and have equal population (though those rules are no longer enforced by statute).

And in 2022, a Democratic-led Congress came close to passing legislation that would have banned partisan gerrymandering across the country in congressional redistricting as well as prohibited mid-decade redistricting.

The trainwreck we’re seeing play out in Texas is just the most vivid example of the Supreme Court’s 2019 decision come home to roost. It won’t be easy, but there must be a national fix.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.