Seattle Renews Its Unique Approach to Public Campaign Financing

The democracy vouchers program hands residents $100 to donate to local candidates and it’s credited with broadening civic involvement. Voters on Tuesday extended it by 10 years.

| August 8, 2025

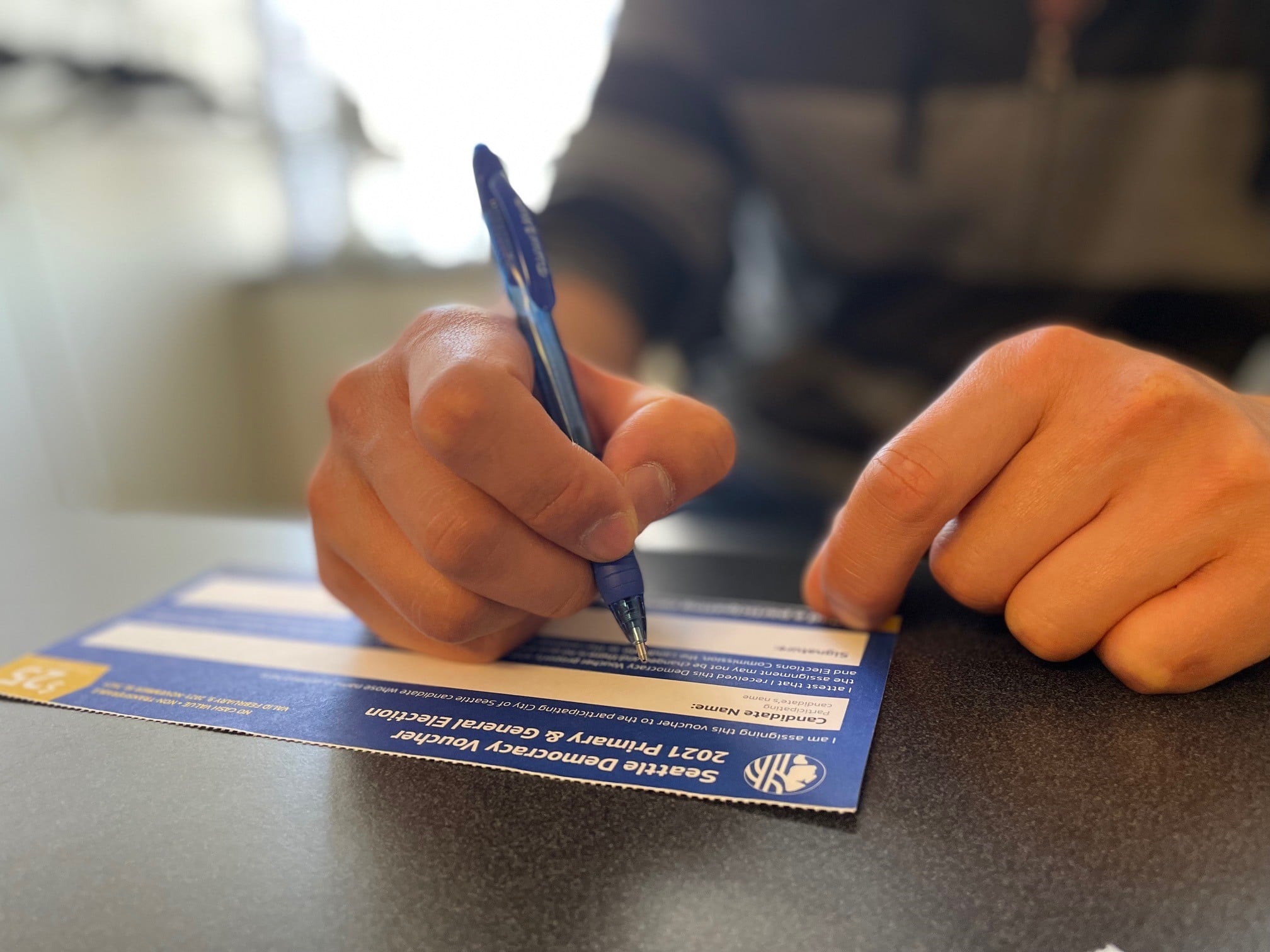

Seattle is poised to continue its experiment in public campaign financing. Voters on Tuesday renewed the city’s democracy vouchers program, which provides each adult Seattle resident with four $25 vouchers they can donate to local candidates of their choice.

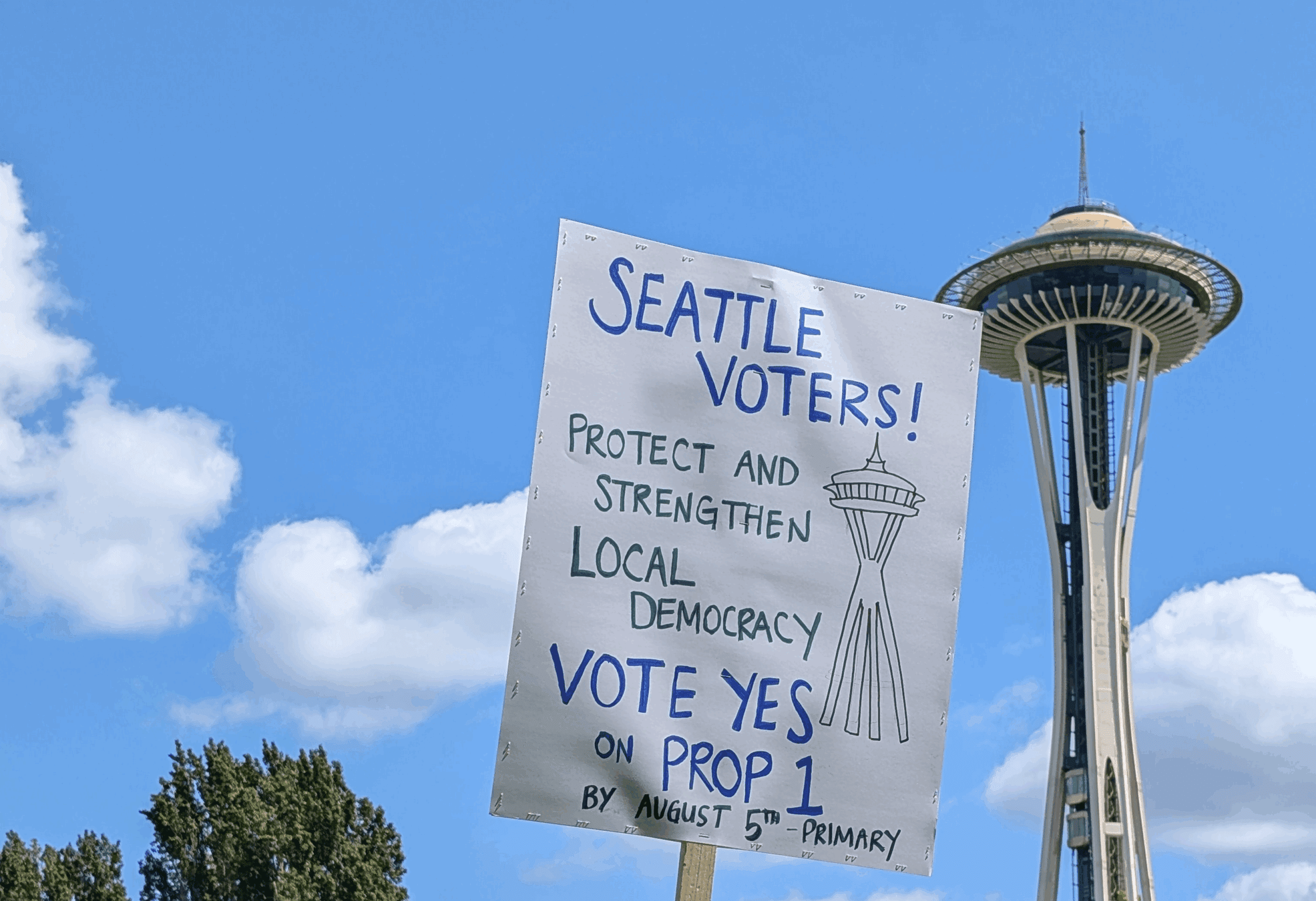

The ballot measure, which leads by 17 percentage points as of Friday evening, will generate $4.5 million in property taxes a year to fund the program for the next decade. Had it failed, the tax levy that voters approved in 2015 would have expired, winding down the democracy vouchers.

Supporters celebrated the measure’s success, which comes eight years after Seattle first implemented the program. Since then, studies have found that the vouchers have strengthened the influence of everyday residents on local politics and allowed a wider array of candidates to launch campaigns, decreasing their reliance on big-money donors.

“Seattle showed the country what’s possible when we commit to making local elections more inclusive and accountable,” said Cinthia Illan-Vazquez, executive director of the Washington Bus, an organization that promotes civic engagement among youth. “At a time when federal courts and extremist politicians are attacking voting rights and blocking campaign finance reforms, Seattle voters just sent a powerful message: We will protect our democracy and keep building toward a system that truly represents all of us.”

Despite several attempts to export the idea, democracy vouchers remain unique to Seattle. Voters in Oakland, California, approved a similar program in 2022 but city officials have not funded its implementation.

Other American cities that publicly finance campaigns tend to use an approach known as matching funds; there, the government gives money to candidates to match the donations they’ve already raised. But that means candidates face a heavy burden to keep raising big sums from wealthy donors. With democracy vouchers, candidates still have to secure some donations to qualify in the first place, but the amount of money they’ll then receive comes down to whether they appeal to ordinary residents—each of whom becomes a potential small donor.

“You don’t need any of your own funds to participate, and so it makes it a lot more accessible than just a matching program,” said Shannon Grimes, a senior researcher with Sightline Institute, an organization that worked on the original program design. “And so it means that it can really reach those underrepresented folks.”

Nilu Jenks, who ran for city council in 2023, says she wouldn’t have been able to mount a viable campaign without this program.

“When my neighbors pushed me to run for office, I questioned how someone like me was going to raise millions of dollars,” Jenks told Bolts in a statement. “Democracy vouchers changed everything. Instead of spending my time calling people with money to ask them to donate, I knocked on thousands of doors and really got to understand my community’s needs better.”

Proponents of the program also highlight how it has increased the number and diversity of people donating to local elections, drawing in Seattleites who otherwise may be disengaged from city politics. According to a University of Washington study, over the first two cycles of the program, Seattle saw a 350 percent increase in the number of unique donors.

Another, more recent study, conducted by researchers at Stony Brook University and Georgetown University, found that the donors using democracy vouchers were more likely to be young and lower-income.

These changes are making local elections more competitive and creating a tougher road for incumbents to win reelection, according to the University of Washington study. Alex Gallo Brown, campaign manager of Katie Wilson, the progressive mayoral candidate who is currently leading Mayor Bruce Harell in Tuesday’s primary, thinks that democracy vouchers were critical to Wilson’s success.

“It really takes some of the corporate influence out, and it allows someone who has never held political office, who lives in a one-bedroom apartment, who doesn’t have a car, to be competitive,” Brown told Bolts. “It’s really leveled the playing field.” (Harrell, Wilson’s opponent, backed the renewal of the program and also used democracy vouchers in the primary.)

Not everyone supports the program. The Seattle Times editorial board recommended a “No” vote on the ballot measure this summer, saying it was meant “to reduce outside money in city campaigns, but it has not limited independent expenditures, so big-money interests still get to play.”

While the share of donations that comes from outside the state has dropped considerably over the past decade, the total amount of dark money spent in Seattle city elections has soared, as has the overall spending. Proponents of the program have said the surge follows a national trend.

The Seattle Times board also said the program “has barely moved the needle in terms of voter participation.”

During the 2021 cycle, which featured a hotly disputed mayoral race, 7.6 percent of eligible residents used any of their democracy vouchers; that was the program’s record. Two years later, only 4.7 percent did so.

Proponents acknowledge that the overall number of participants is low. But they also point out that the share of Seattleites who are able to donate to a campaign has grown considerably—just 1.7 percent of adult residents donated in 2015, the last election cycle before the inception of democracy vouchers—and that the current numbers are high by any national standard.

According to Jennifer Heerwig and Brian J. McCabe, two sociologists who authored the book Democracy Vouchers and the Promise of Fairer Elections in Seattle, the rate of residents who are contributing to local candidates is much higher in Seattle than other American cities.

The program’s design also limits how many residents can participate: The candidates have strict fundraising caps that limit how many vouchers they can accept, which means not all the vouchers mailed out in a given cycle can actually be used as candidates hit those caps.

Proponents of democracy vouchers say they’re committed to broadening participation: The measure that passed this week instructs city officials to convene a working group in 2026 to consult with people who’ve used the program and recommend improvements to the mayor and city council.

The program already includes funding for grants to community-based organizations to educate voters on how to use their democracy vouchers, but some advocates want to increase the budget for this outreach.

Another possible reform would be to raise the cap on the number of vouchers a candidate can accept. That would allow candidates to seek donations from more residents than they can currently.

Stephen Paolini, a Seattle-based political consultant at Bottled Lightning Collective who has worked with local candidates, thinks the program needs to be tweaked so democracy vouchers can better compete with independent expenditures.

Currently, when a candidate benefits from large amounts of outside spending, opponents can raise more money—but the maximum they can obtain from democracy vouchers doesn’t change, only the amount they get from regular cash. Plus, critics say this comes too late in the campaign to make much of a difference. Paolini suggested requiring that independent expenditures be disclosed earlier, and allowing democracy vouchers to be used once the cap is lifted. Lifting fundraising caps could also make it less attractive for outside groups to get involved, Paolini argued.

“It’s not quite the national model we want it to be yet,” Paolini told Bolts of Seattle’s democracy vouchers. It still has some kinks to work out, which is why other cities haven’t really adopted the program yet. But we can show them this program can work by improving it.”

He said, “We promised the country that we would show them a new way of doing elections, and I feel like we have to live up to that by continuing to improve this program.”

Editor’s note: The article was updated after Seattle updated its election count on Friday evening.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.