Reforms for Alabama’s Troubled Parole Board Remain Elusive, Despite Bipartisan Support

After years of a near-full blockade on parole, Alabama is now releasing more people. But grants remain low, prisons are overcrowded, and oversight efforts stalled again this year.

| June 12, 2025

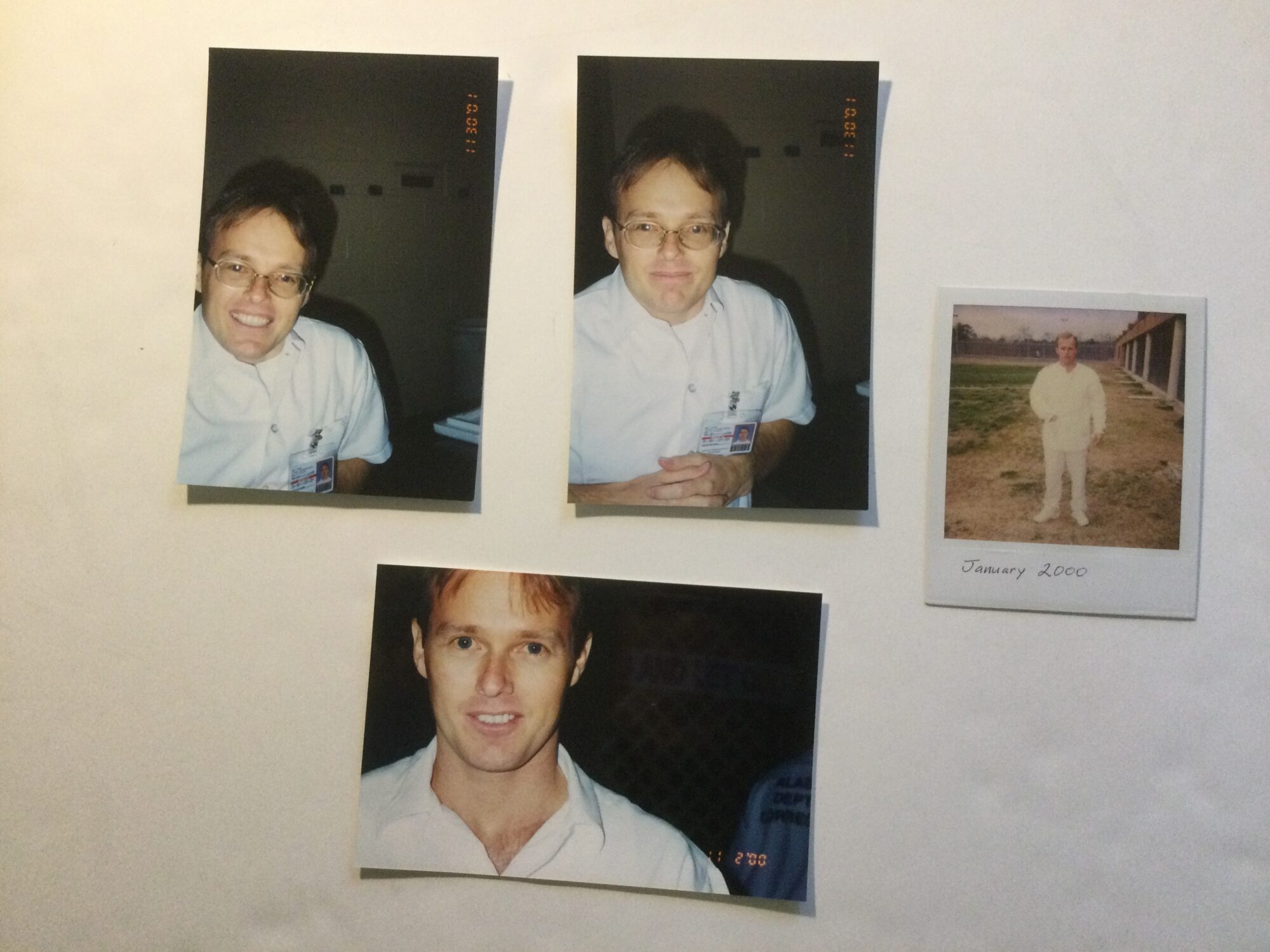

Terry Townsend, who was released on parole last fall after spending two decades behind bars in Alabama, calls his freedom “a miracle.”

Townsend had been previously denied parole twice, first in 2019 and then again in 2022. Each time, the parole board rejected him because of his crime, burglary of a pharmacy, and because they deemed him to be at high risk of reoffending despite his application containing evidence that he had changed while incarcerated. He had a clean disciplinary record, 20 certificates from completing prison programs, recommendation letters from prison employees, and the promise of a job when he got out.

Townsend began applying for parole just as releases plummeted in the state, making Alabama’s parole board one of the toughest in the nation. Over the past five years, the board freed just 15 percent of prisoners who applied. In 2023 grant rates dropped to eight percent, the lowest point in at least a decade.

But last year, amidst heightened scrutiny of the board from lawmakers and the media, releases trended upward for the first time since 2017, with the board granting parole to one in five prisoners who applied in 2024. This year, releases are up again, with 21 percent of applicants winning parole through April, the last month with available data from the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles.

But even with those changes, the board is not paroling as many prisoners as it could be, according to its own guidelines for deciding releases—which, per the board’s most recent report, say that about 80 percent of applicants meet the criteria for parole.

Townsend said he has a lot of friends still incarcerated who should be free.

“We do have some people who need to be locked up, but there’s a lot of people in there right now that shouldn’t be in there because of the parole board,” he said. “I know many guys. I know guys right now that I would put my parole on that could get out and be successful, given an opportunity, but they can’t get the opportunity because they can’t get a fair shake.”

The low rate of parole grants in Alabama has contributed to dangerous overcrowding in the state’s prison system, which is the subject of a lawsuit by the U.S. Department of Justice over deadly conditions. Alabama lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have responded by pushing reforms aimed at making the process fairer. The legislature recently considered a bill to create oversight of the parole board and clearer guidelines for deciding applications, along with another bill allowing prisoners to virtually attend their parole hearings. But both bills failed to pass before Alabama lawmakers ended their session last month.

Alabama’s parole board used to release more than half of applicants. But in 2018, a man out on parole killed three people, including a child, causing Governor Kay Ivey and Attorney General Steve Marshall to pressure board members to stop releasing people. Former board chair Lyn Head told Bolts in 2023 that she changed how she voted and denied more cases because she was afraid of losing her job.

The legislature passed a law in 2019 that gave Ivey more control over who sat on the board. When Head resigned that year, Ivey replaced her with the current chair, Leigh Gwathney, a senior prosecutor overseeing violent crimes who also worked under Marshall in the attorney general’s office.

As chair, Gwathney has voted against parole in most cases, regardless of prisoners’ applications. Researchers from the ACLU of Alabama observed parole hearings in the summer of 2023 and found that she voted to keep prisoners incarcerated in 245 out of 251 cases, and in all of the cases in which the attorney general’s office voiced support against release.

Parole used to be an important mechanism for easing overcrowding. As of March 2025, roughly 20,800 prisoners were incarcerated in the state’s correctional facilities. They’re built to house almost half of that: 12,115.

Alabama officials are in the process of building a 4,000 bed, $1.3 billion mega-prison set to open next year. But the facility will only replace existing beds in the corrections system and not create additional capacity.

State Representative Chris England, a Democrat and ranking member on the House judiciary committee, told Bolts that the boost in legislative momentum to change the board was “unavoidable.”

“The issues with the board got to the point where they were so blatantly disregarding oversight and the law,” England said, adding that reforms are necessary to prevent more prison building and help save taxpayers money. “If the parole board effectively isn’t using the parole process, it becomes prohibitively expensive, meaning we won’t be able to build prisons large enough to accommodate the population that the parole board continues to create.”

The Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles did not respond to requests for comment.

Last month, the Alabama Senate threatened to withhold funding for the board if it didn’t update the guidelines for determining whether someone should get parole. Under state law, the board is supposed to update them every three years using evidence on prior releases, but it hasn’t done so since 2019. The board ultimately provided new guidelines that make it more difficult for prisoners to win parole by putting additional weight on their crimes and discipline they receive while incarcerated.

Lawmakers are currently evaluating the guidelines and the public can weigh in on them until July 4. After that, the legislature will decide whether to accept them or ask the board to go back to the drawing board.

During this year’s regular session, England introduced House Bill 40, which would have established an 11-member group to create evidence-based guidelines for board members to use in deciding whether to release prisoners. The legislation would also have required the board to make a written statement anytime they deviate from the guidelines and allow for prisoners to appeal their parole decisions.

England has introduced similar bills for the past three years without success. Unlike previous sessions, however, this year the legislation made it out of a House committee, although it didn’t advance further. He said he plans to introduce it again next year.

“The parole board needs oversight,” he said.

State Senator Will Barfoot, a Republican, introduced a separate bill for the second year that would have allowed prisoners to virtually attend their hearings and make a statement. The bill also stalled after making it out of a Senate committee.

Alabama and Georgia are the only two states where prisoners are not permitted to participate in their parole hearings, Alison Mollman, interim legal director of the ACLU of Alabama, told Bolts. Prisoners may write a letter to the board or send in a video but there’s no guarantee that the board will view either because of time constraints; hearings are short and supporters are given two minutes to speak.

“It’s one thing to read about a person on a piece of paper. It’s another thing to be able to ask them questions, to hear from them directly,” said Mollman. “So we think this is a solution that would only make Alabama’s system of parole stronger and would provide more clarity, consistency, and credibility to this system.”

Barfoot’s bill also won the support of Victims of Crime and Leniency, or VOCAL, a victims rights organization whose representatives attend parole hearings to provide support and often speak in opposition to releasing prisoners. That’s because the bill would have also allowed for victims and law enforcement, who are already permitted to physically attend and speak at parole hearings, to virtually participate in those proceedings. Wanda Miller, VOCAL’s executive director, told Bolts that it can be difficult or impossible for victims to attend hearings because they have to travel to Montgomery or are unable to get off of work. Miller said allowing them to participate via videoconferencing would give more people an opportunity to weigh in.

“In our process of working through this, it became apparent that this could be beneficial to everyone concerned,” she said of the legislation.

Miller, whose organization opposed England’s bill to establish oversight and fairer standards for the boards, says she expects the legislature to continue to try to make changes to the parole board next year. She says she’s planning to approach the bills with an open mind while ensuring that lawmakers take any impact on victims into consideration.

“It’s a very complicated subject. There’s a lot of people on both sides that have very valid issues,” she told Bolts. “I just don’t ever want the world to get to the point where we just dismiss the people who were harmed.”

Mollman, of the ACLU, says she’s optimistic about the future of reforms in the state in light of some of the debates she witnessed this year. “No matter party affiliation, no matter where we have differences, we all agree that when people are ready to safely re-enter society, we should support them to get their home, to get them home to their families,” she said. “Legislators have started to see the reality of this problem and are beginning to take action.”

Next year’s legislative session will be the last of Ivey’s tenure as governor since she cannot seek reelection in 2026. U.S. Senator Tommy Tuberville is the current frontrunner to replace Ivey, and Marshall, the attorney general, is currently running for Tuberville’s seat in the U.S. Senate.

Townsend, who is now employed full-time at a packaging company, says he’s thriving on parole. Still, he wants to see lawmakers continue to apply pressure to the board.

“We’re hoping that they’ll pass this bill or that bill. And guess what? Seems like it always gets knocked down because of politics,” he said.“ There’s got to be changes,” he said of the parole board, “and it’s going to be up to the legislature to force their hand.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.