The Anti-Carceral Feminist Who Wants to Be DA

Pamela Price, a civil rights lawyer running for DA in California’s Alameda County, sees criminal justice reform as gender justice. Can she resolve the role’s contradictions?

| November 1, 2022

This article was produced as a collaboration between Bolts and The Nation

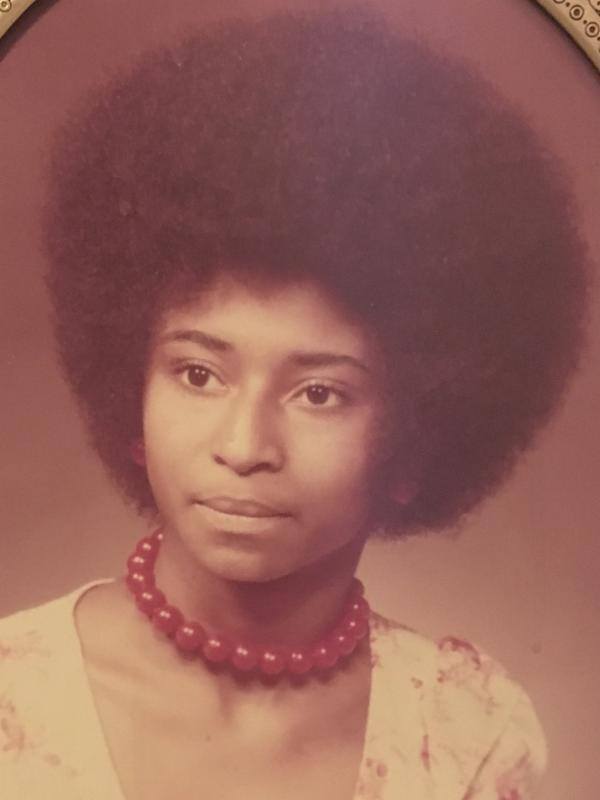

Today, Pamela Price is an accomplished civil rights attorney, but her earliest interactions with the law were unfailingly negative. Devastated and enraged by the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., she organized student demonstrations as a teenager—and was tossed in jail for it. After running away from home, she bounced between the foster-care and youth justice systems. “My juvenile experience led me to think, ‘Oh, these lawyers, this is all bad,’” she recalled. “I didn’t want to be part of a legal system, or even a political system. It took years for me to actually get back into being active.”

Price came of age during the second-wave feminist movement of the 1970s, when women’s rights activists fought to make the law reflect the equality between the sexes, sought justice for abused women—and ultimately, turned to the criminal legal system to fight gendered oppression, with sometimes disastrous consequences for poor and minority communities. In many ways, she embodies that paradox: the capacity of the law to advance gender justice and its enormous potential for damage. She became the public face of Title IX in college, and would go on to argue groundbreaking sexual harassment and racial discrimination cases in civil court in the ’90s and 2000s. In the 1970s, she advocated for self-defense rights for battered women, and was prosecuted for trying to protect herself and her child from her abuser.

Now, Price is vying to become the next district attorney of Alameda County—a fraught proposition in its own right.

Prosecutors have played an instrumental role in using the specter of violence against women to advance a carceral agenda. Take the current Alameda DA, Nancy O’Malley, who established a reputation as a tough sex crimes prosecutor; served as president of the California District Attorneys Association, which frequently lobbies for tough-on-crime policies; and has instituted domestic-violence and sex-trafficking initiatives that advocates warn only sweep more women and girls into the criminal legal system.

Meanwhile, some critics believe that gender justice remains a blind spot for the progressive prosecutor movement. Getting tough on men who hurt women has long been a bipartisan crowd-pleaser: Conservatives love punishment, while liberals hate the idea of being accused of condoning sexual violence. Including gender-based crimes in any reform platform is a political risk.

“You have a core progressive idea that says mass incarceration is problematic, we need to do something to counter it,” said Leigh Goodmark, a professor of law at the University of Maryland. “And you also have a core belief that gender-based violence is deeply wrong, and we have to do something as a society to combat that. And progressive prosecutors often see those two things as being in tension.”

Price, who unsuccessfully challenged O’Malley in 2018, is now running to fill the seat left open by O’Malley’s retirement, representing Oakland, Berkeley, and the rest of the East Bay. Price will face deputy DA Terry Wiley, who is endorsed by O’Malley. In Price’s view, advancing gender equality and dismantling mass incarceration aren’t opposing goals—they need to be pursued together. If women’s liberation is contingent on racial justice, and racial justice necessarily requires women’s liberation, then you can’t fight for one without fighting for the other.

But to do so will require an approach that transcends the schisms of past liberation movements—and diverges in nearly every respect from the traditional role of the DA. “I’m very much aware that I cannot be complicit in allowing the system to be manipulated based on white supremacy or any kind of gender politics that is used to further criminalize Black and brown people,” Price told me. “The challenge for me is that I’m saying I want to reduce and eliminate mass incarceration, but I’m going to be working in an office [where] that’s the whole purpose.”

Price arrived at Yale in 1974, an emancipated minor on full scholarship. During her junior year, she studied abroad in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. “For the first time in my life, it was full in my face that you’re being treated differently not because you’re Black—because everybody’s Black, right?” she said, laughing. “You’re being treated differently because you’re a woman.”

Price came home changed. “I still understood that my people were oppressed in this country,” she said. “But I was a feminist on top of that.”

In 1977, after being propositioned by an instructor who dangled the promise of a better grade, Price joined a lawsuit brought by several female students against male professors who’d raped or harassed them. The radical feminist theorist Catharine MacKinnon wrote the case’s legal argument, recasting Title IX, then seen as a purely sports-related statute, as a broader tool for gender equality.

“We were in uncharted territory,” Price recalled. “We knew that if we could get Title IX enforced at Yale, it would be enforced everywhere.” In a way, it was her first political campaign. “We held rallies, we did press releases, we raised money,” she said. “And when the case went to trial, we packed the courtroom.”

Of the five plaintiffs, Price was the only Black woman. Soon, after the court determined the others lacked standing, she found herself the only remaining plaintiff. Alexander v. Yale would lose in court, but the women’s efforts won them what they wanted: Yale instituted a grievance policy. Then, so did other universities. “The benefit for me from Alexander,” she reflected, “was knowing that the law is not always where it needs to be—and that as a lawyer, and certainly, as a legislator, as a leader, you have the opportunity to make the law be what it needs to be for everyday people.”

Price went on to Berkeley Law, where she became interested in the emerging legal theory of self-defense for survivors of domestic violence, then more commonly called battered women. She got involved in the case of a woman charged with murder after she killed her abusive husband. Price walked away from the experience disgusted by both the prosecutor’s zeal to punish her and her lawyer’s coziness with the rest of the system. Realizing that Alameda County prosecutors were going after women who defended themselves in other cases too, Price helped form the Bay Area Defense Committee for Battered Women.

Angela Davis and the pioneering lesbian rights activist Del Martin sat on the board for the committee, which took complaints, showed up at court hearings to advocate for women, and educated their defense lawyers on the relevant legal theory. The solidarity they offered was a balm, but it didn’t change outcomes. “The system just grinds people up,” Price said.

During the 1970s and ’80s, battered women’s advocacy groups sprung up around the country. At first, the solutions that feminists advanced were economic ones, like jobs and welfare programs, according to Aya Gruber, the author of The Feminist War on Crime and a professor of law at the University of Colorado. Domestic violence was viewed as a function of disenfranchisement and white supremacy. But as activists sought broader recognition of the movement, they emphasized that abuse happened across racial and class lines, and homed in on a narrower avatar for the issue: What Gruber calls “the white woman behind enormous sunglasses at the club.” Welfare wasn’t a suitable solution for such a victim.

“The angle for these women is separation and policing, and then they can go divorce their rich husbands, they have this arrest in their back pocket, and they can get child support,” Gruber said.

In 1984, as Goodmark details in her book Decriminalizing Domestic Violence, three things happened that would change the course of the movement: The federal government officially took the position that intimate partner violence required the criminal legal system; a woman whose husband had severely injured her successfully sued her town on the grounds that police hadn’t acted sooner; and a pair of researchers published the ominously titled study “Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment,” which suggested arrests were an effective intervention into spousal abuse. The authors cautioned that their findings, which only compared arrest to other forms of police response, were too preliminary to be acted on, and future studies would undermine their conclusions—yet police across the country adopted mandatory arrest policies for intimate partner violence calls.

Tellingly, though American feminists never secured the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment, they did get the Violence Against Women Act in 1994, which dedicated the majority of its funding to the criminal legal system. By 2013, though total funding for VAWA had nearly doubled, the percentage dedicated to law enforcement had gone up so much that fewer dollars were going to social services than at the time of its passage, nearly two decades earlier.

By sidelining the needs of working-class women of color and turning toward police as the solution, second-wave feminism foreclosed on its liberatory potential for women everywhere. In turn, one of the movement’s most enduring legacies has been not the successful reduction of gender-based violence, but its role in the expansion of the carceral state. All that money and law-enforcement training failed to meaningfully curtail domestic abuse rates. During that time, the country’s ballooning prison and jail population confined and circumscribed the lives of millions, mostly poor men of color. The feminist movement was by no means the sole cause, but the threat of violence against women—implicitly assumed to be white—provided cover and justification for more incarceration.

The influence of this carceral feminism can be detected in parts of the MeToo movement’s vision of criminal punishment as justice. “Everybody loves to be outraged and say, ‘We’ve got to have change,’ and ‘Time’s up,’ and ‘Now, now, now,’” said Gruber. “Those things actually turn into laws. And we have no idea how those laws will operate and most of the time, if they’re criminal laws, there’s somewhere, someplace where it’s not going very well for a lot of marginalized people.”

Men still represent the great majority of those incarcerated, meaning that women are often seen as indirect victims of the system, subject to the vast social, emotional, financial, and psychological toll of supporting an incarcerated loved one. But Gruber, Goodmark, and organizers who fight for intersectional gender justice stress that these policies also directly hurt women and children.

“When somebody is envisioning a young person who’s been exploited, they have a very clear image,” said Jessica Nowlan, president of Reimagine Freedom. “They’re thinking of Polly Klaas”—the 12-year-old girl whose abduction and murder led to the passage of California’s Three Strikes Law in 1994. Young Women’s Freedom Center, one of Reimagine Freedom’s associated organizations, works with young women and nonbinary and trans youth in the East Bay and beyond, many of whom are themselves being exploited: abused or pushed into sex work, either by an individual or by economic necessity. Nearly all of them have been arrested multiple times and have spent time in jail, according to the freedom center. A system that only recognizes Polly Klaases as victims inevitably ends up drawing women and girls who don’t look like her into its net.

“One of the things that became clear to me was the ways in which women were being targeted by the system,” said Gina-Clayton Johnson, who runs the Essie Justice Group, an organization for women with incarcerated loved ones. “Women are being incarcerated at rates that outpace men today… Our impulses for punitivity absolutely have extended directly to women who have been in situations of domestic violence.” The mandatory arrest policies instituted across the country did result in more men being arrested for domestic violence, but they had another, unintended, consequence: Arrests of women increased too.

Price’s history helps illustrate why. After she graduated from Berkeley Law, the father of her child, who had been abusive during their relationship, kept showing up at her house and refusing to leave. Left with few options, Price would call the police, who seemed to grow more and more callous toward her predicament. One day, things escalated.

“I was outside, and they told me that they were going to give my 3-month-old nursing baby to this person,” she told me. She speaks calmly about this now, but it took her many years to be able to talk about it. “And I said: ‘No, no, no, no, that cannot happen.’ So I went back into the house to get my baby. And they dragged me out of my house and took me to jail.”

The DA’s office chose to move forward with the case, charging her with disorderly conduct and resisting arrest, and urged her to take a plea. Goodmark said that this unnecessary prosecution of survivors still happens regularly, even though prosecutors have the discretion to decline to bring cases. “There are lots and lots of reasons that women are pleading to things that they could have strong defenses to,” she told me.

Price, however, knew her way around the law, and she knew lawyers. Her boss at the time agreed to represent her. So she went to trial: “I told the jury what happened, and they were like, ‘Are you kidding me?’” She was quickly acquitted. “But just going through that was hella scary,” she said. “I was a young single mom, I was waiting on my bar results—you know, they just could have destroyed my whole life.”

Price had experienced, not for the first time, how the state could harm rather than help victims of abuse—what she now calls being a “double survivor.” As a young mother, she had an idea of how she would have wanted the police and DA’s office to respond, she said, “but I knew that from my own experience with the Bay Area Defense Committee for Battered Women that that was not part of the system.”

Today, though, she’s come to believe that the system could function differently. “I got to learn to be a lawyer and to use the law in some really powerful ways to be an advocate for women,” Price told me. For many years, she brought lawsuits on behalf of women forced to endure sexual harassment in the workplace, including many prison guards. Fighting against the California penal system underscored to her just how much mass incarceration harms everyone.

Still, Price said, when it came to the idea of running for DA, “I had to be persuaded that a civil rights lawyer could really have an impact.” The single most important thing that changed her mind, she said, was a TED talk by a young Black former prosecutor named Adam Foss, who discussed his epiphany about the power that prosecutors hold over the lives of people they charge, and how they might practice differently. (Foss became an influential advocate for criminal legal reform, but was plagued by allegations of inappropriate conduct during his time at the Suffolk DA’s office. The Manhattan DA charged him with rape this August).

Being confronted by the racial disparities on display in the East Bay further galvanized Price. “If you are a Black person in Alameda County, you are 20 times more likely to be incarcerated than a white person,” she said. “That’s an unacceptable, intolerable level of racial injustice that just called me to action.”

Though she has been targeted by the criminal legal system and worked for several years as a community defense attorney in San Francisco, Price has mostly used civil law to advance gender justice. If she wins in November, she would take over an office that has long used violence against women to justify opposition to criminal legal system reforms. Historically, DAs “bought into the idea that they could be the people who saved victims of intimate partner violence,” said Goodmark. “You also see some prosecutors become very out-front advocates for the role of the criminal legal system in ending gender-based violence. And they start doing that kind of hardcore lobbying that says: ‘The work is done by us. We are the central players in this system. And if you just resource us properly, we’ll be able to do that work.’”

Price has said she wants to take a closer look at both of O’Malley’s signature initiatives: the Family Justice Center, a clearinghouse for domestic violence and sexual abuse; and the Human Exploitation and Trafficking (HEAT) unit. She fears that both programs do little to prevent gender-based violence, use victims against their will to obtain prosecutions, and often fail to provide women with the resources they need to escape an abusive situation. HEAT, she said, “is heralded as this innovative program, but there’s so many people that are not being served.” She said she would not prosecute women for engaging in sex work, and suggested other ways to enforce anti-sex-trafficking measures without criminalizing individuals—like targeting hotel chains that facilitate sex trafficking.

O’Malley’s office defended their work on HEAT and the Family Justice Center in a statement, stressing their partnerships with non-governmental organizations that employ survivors of gender-based violence. When asked whether the office requires victims of intimate partner violence to testify against their abusers, the office replied that the HEAT unit doesn’t compel victims of sex trafficking to testify, but did not respond to a request for clarification about the policy toward other victims of interpersonal violence.

To many local advocates, programs like HEAT are primarily drivers of system involvement and incarceration: “To me, it’s just another kind of disguise for law enforcement to access dollars that they shouldn’t have,” said Nowlan, calling on Alameda County to implement an expansive diversion program as an alternative.

Julia Arroyo, the co-executive director of Young Women’s Freedom Center, criticized the complicated network of DAs, agencies, and community organizations that try to respond to issues of abuse and exploitation as both paternalistic and ineffectual. “You just kind of get entangled into this system, and it creates this hyper-focus and supervision on your life, but often people are still needing to get connected to housing or different resources,” she said. “I know what it feels like to be criminalized, and I know what it feels like to be wrapped with love and support from a community that will not let you fail.”

“We envision community solutions, we envision community interruption, we also envision community healing,” said Nowlan. “And that does have to happen outside of the system.”

Goodmark said that DAs should stay away from restorative justice initiatives because of the implicit threat of prosecution if participants drop out, a view shared by some practitioners and critics of the criminal legal system.

Price vehemently disagrees. “Our goal is to keep people out of the system and to create a pathway that does not involve punitive prosecution,” she said. The philosophy of restorative justice, she said, can also serve a modus operandi that elevates crime victims’ needs rather than using them to secure as many prosecutions as possible.

Price says that DA’s offices can and should stop compelling victims to participate in cases against their will and stop pursuing charges against survivors of intimate partner violence who defend themselves—positions in line with activists who say she should try to narrow the system’s scope rather than expand it in the name of gender justice. “My biggest, I think, piece of advice to any prosecutor is to shrink your footprint tremendously,” said Clayton-Johnson of the Essie Justice Group. “I think that the most important thing is to lean far away from seeing incarceration as the solution to gender-based harm and violence.”

Clayton-Johnson also urged prosecutors who want to focus on gender justice to look at large-scale criminal behavior that is rarely enforced but affects people’s ability to lead productive and happy lives, like environmental racism and wage theft. “There’s a root cause orientation that Black feminism requires,” she said. “To just start to really think systemically about how I can curb harm—is what I would be excited for a prosecutor to do.”

In other words, to go back to the original solutions of the second wave feminist movement, before it veered down the path of criminalization—but to do so from the very heart of the criminal legal system. Is such a thing possible, or is it a contradiction in terms?

Price knows that she’s wading into murky terrain. But her life work has taught her that it’s worth a try. “Personally, professionally, I have learned how this system works,” she said. “And I very much believe that people made this system, and we can remake it.”

*This story was updated to clarify Nowlan’s current job title.