Powered by Native Voters, Ranked-Choice Voting and Open Primaries Survive in Alaska

Alaska’s predominantly Native regions delivered huge margins against repealing the state’s new elections system, despite facing continued logistical challenges to voting.

| November 22, 2024

Alaskans appear to have narrowly rejected Measure 2, a ballot initiative that would have repealed the state’s open primary and ranked-choice voting system.

The system, first approved by voters in 2020, quickly drew Republican opposition after a Democrat flipped the state’s single U.S. House seat in 2022, the first time it was used. But the state’s predominantly Native areas formed a bulwark to defend it this fall, despite notorious barriers to political participation in these more rural and remote regions.

The measure to repeal the system trails by 664 votes, or 0.21 percent, with all ballots counted. The small margin means that proponents of repeal may ask for a recount in December, though no statewide recount has changed a lead of this size in this century.

Areas with large Alaska Native populations provided the winning margin against repeal. Across the state’s three majority-Native House districts, the ‘no’ vote is leading by 2,960 votes, 64 to 36 percent.

“This is definitely demonstrating the power of us as a block,” said Michelle Sparck, director of Get Out the Native Vote. “We tend to scream into the void that we count, that we matter. If we vote to our full power, which is a quarter of the statewide vote, then we would see a lot more of a representative government.”

Alaska Native organizers rallied to defeat Measure 2, Bolts reported in September, and they worked to educate people on how the new system works.

The Alaska Federation of Natives (AFN) formally endorsed the open primary and ranked-choice voting system last year at its annual convention, saying that the new rules afford Native voters “more freedom, more choice, more influence, and greater participation.” They reaffirmed their support at their convention in October, right before the Nov. 5 referendum.

In the lead-up to Election Day, Native leaders worked to grow turnout by hosting events in dozens of rural villages, spreading the word through radio, and recruiting young people to volunteer at the polls. They also closely monitored each precinct to get ahead of logistical challenges that come up in remote areas, from a lack of equipment to winter storms.

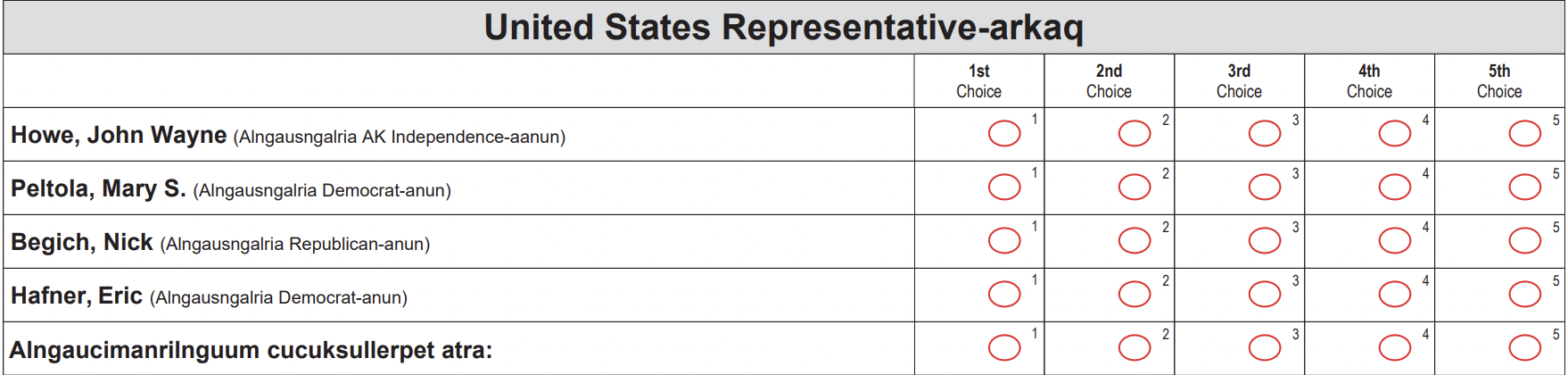

In Alaska’s new system, all candidates regardless of party run in one primary that is open to all voters. Then, the top four candidates advance to the general election, at which stage voters can rank them. The state then tabulates the ballots and rankings until one winner emerges.

Native organizers told Bolts that they saw the first half of this reform—the open primary—as the most valuable to their aims. Under the old system, major parties acted as “gatekeepers,” and candidates had little hope of prevailing without winning their support and approval, Sparck said. But now, voters can pick whoever aligns best with their needs, regardless of party affiliation. The priorities of Native voters rarely fall squarely into the platform of any one party, she added, and the open primary system allows them to support candidates across party lines.

Data suggests that Natives have embraced this option more than other Alaskans. According to a report by Get Out the Native Vote, over 80 percent of voters in predominantly Native districts split their primary ballots in the 2022 primary, choosing some Republican candidates and some Democratic candidates. That is a far higher rate than the state at-large, where half of voters split their ballots.

Many also credited the new system for contributing to the historic election of Mary Peltola, who won a competitive race in 2022 to become the first Alaska Native to serve in Congress.

But Peltola lost this month to Republican challenger Nick Begich. Begich already led Pelota as voters’ first preference by two percentage points. Once the state tabulated the ranked preferences of voters who supported minor candidates on Wednesday, Begich gained more ground. He prevailed 51.3 to 48.7 percent.

FairVote, a national organization that promotes ranked-choice voting, pointed to the results on Wednesday to make the case that the system does not favor any one party. Begich’s win, two years after Peltola’s victory, is “a reminder that the reform is completely party-neutral,” Meredith Sumpter, the president of FairVote, said in a statement.

If the result holds, the failure of Measure 2 may have significant repercussions on state politics: By preserving open primaries, it would signal that Republican officials do not need to worry about surviving a partisan GOP primary in 2026 or 2028. Lisa Murkowsi, the moderate U.S. senator, benefited from the new system in her last reelection race in 2022. In the legislature, Democrats and moderate Republicans have formed a coalition to run both chambers; they hope to attract more Republicans now that open primaries appear to be here to stay.

The outcome of Measure 2 in Alaska stands in stark contrast with the Nov. 5 results in much of the country. Measures to adopt open primaries and ranked-choice voting failed this fall in Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, and Oregon. (Nevadans had approved the measure in 2022, but it needed to pass twice to become law.) Plus, Missouri voters banned localities from using it.

Alaska will remain one of only two states with ranked-choice voting, alongside Maine. It will be the only state with an open primary system, since Maine still uses partisan primaries.

Voters in Washington, D.C., also approved a switch to ranked-choice voting on Nov. 5. Cities including Portland, San Francisco, and Minneapolis already use it in their local races.

In Alaska, the ‘no’ campaign to preserve the current system was led by Alaskans for Better Elections, and it massively outraised and outspent supporters of repeal.

Philip Izon, who led the effort to get Measure 2 on the ballot, did not reply to a request for comment on its defeat. In an interview this summer, he criticized the ‘no’ campaign for being funded by out-of-state groups, such as the Colorado-based group Unite America PAC and the Texas-based Act Now Initiative. He also told Bolts that he had formed Alaskans for Honest Elections, the group that organized the citizens initiative, because the ranked-choice system was so confusing that his grandfather wasn’t able to figure out how to cast his ballot. He faulted the system as a way to tip the scales towards Democrats.

The ‘no’ to Measure 2 did well in Anchorage and in the southern tip of the state. These are areas that tend to be friendlier to Democrats. But it drew support beyond Democratic voters and outpaced Kamala Harris’ share of the vote in the presidential race by nearly 9 percentage points statewide.

The gap between the ‘no’ and Harris was greatest in areas with large Native populations. Four of the six legislative districts where the ‘no’ vote outperformed Harris by the largest margin are the state’s four majority- and plurality-Native districts. That suggests the results in those regions can’t just be reduced to partisanship.

In Alaska’s majority-Native 40th House district, the ‘no’ did 19 percentage points better than Harris. Voters there voted against repeal 61 to 39 percent, even as Harris lost to Republican Donald Trump 51 to 42 percent.

The ‘no’ also prevailed with more than 60 percent of the vote in the 38th and 39th districts, the state’s two other majority-Native districts.

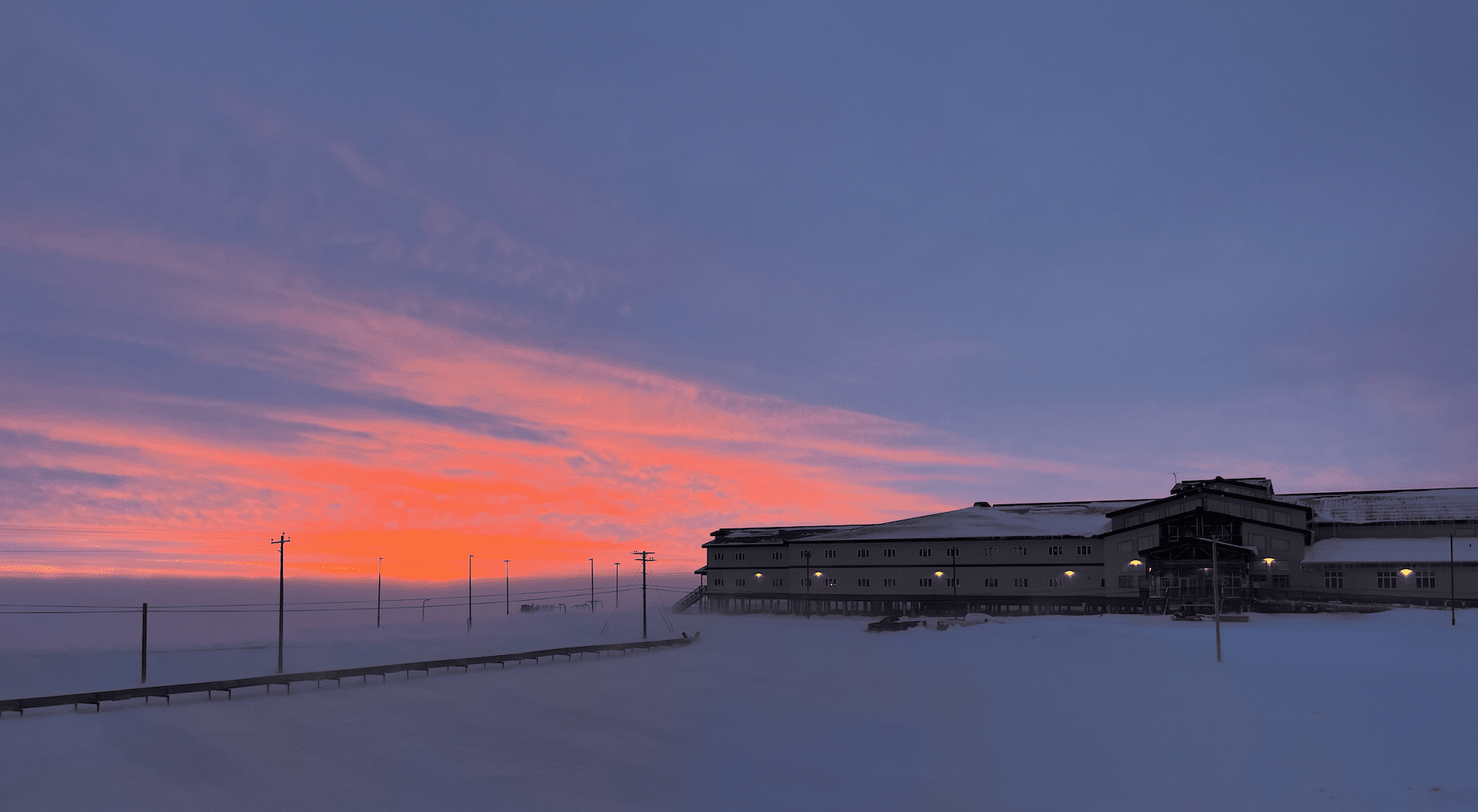

These districts are part of the Bush, a region with harsh weather and large distances between isolated villages and polling places that can discourage potential voters and make organizing difficult.

The region has a history of disenfranchisement. The state often does a poor job of ensuring people have access to the ballot and some communities lack proper accommodations for voting information and ballots in their languages, despite those protections being guaranteed by the Voting Rights Act.

Native organizers this fall made a mammoth effort in order to ensure that registered voters in remote villages disconnected from roadways could still participate in the election.

Sparck told Bolts that, in the small village of Newtok in western Alaska, voters were caught off guard when they learned just before Election Day that the state had no plan to set up a polling place, even though it was a designated precinct and there had been one there in past elections. There are no roads connecting Newtok to any other polling places; the nearest location would have been across the Ningliq River, which was frozen and impassable by boat. The village also has no post office, ruling out mail voting as a solution.

Newtok is a coastal village that has begun collapsing into the ocean due to rising tides brought on by climate change. Most residents have abandoned Newtok and moved to a nearby village across the river, but dozens have yet to relocate.

“They assumed that Newtok didn’t exist anymore, without realizing there were still voters in town,” Sparck said. “Those folks would have been completely left out of the entire process. As difficult as it was, we were able to salvage some level of voting. The system was not prepared to work with a region like that.”

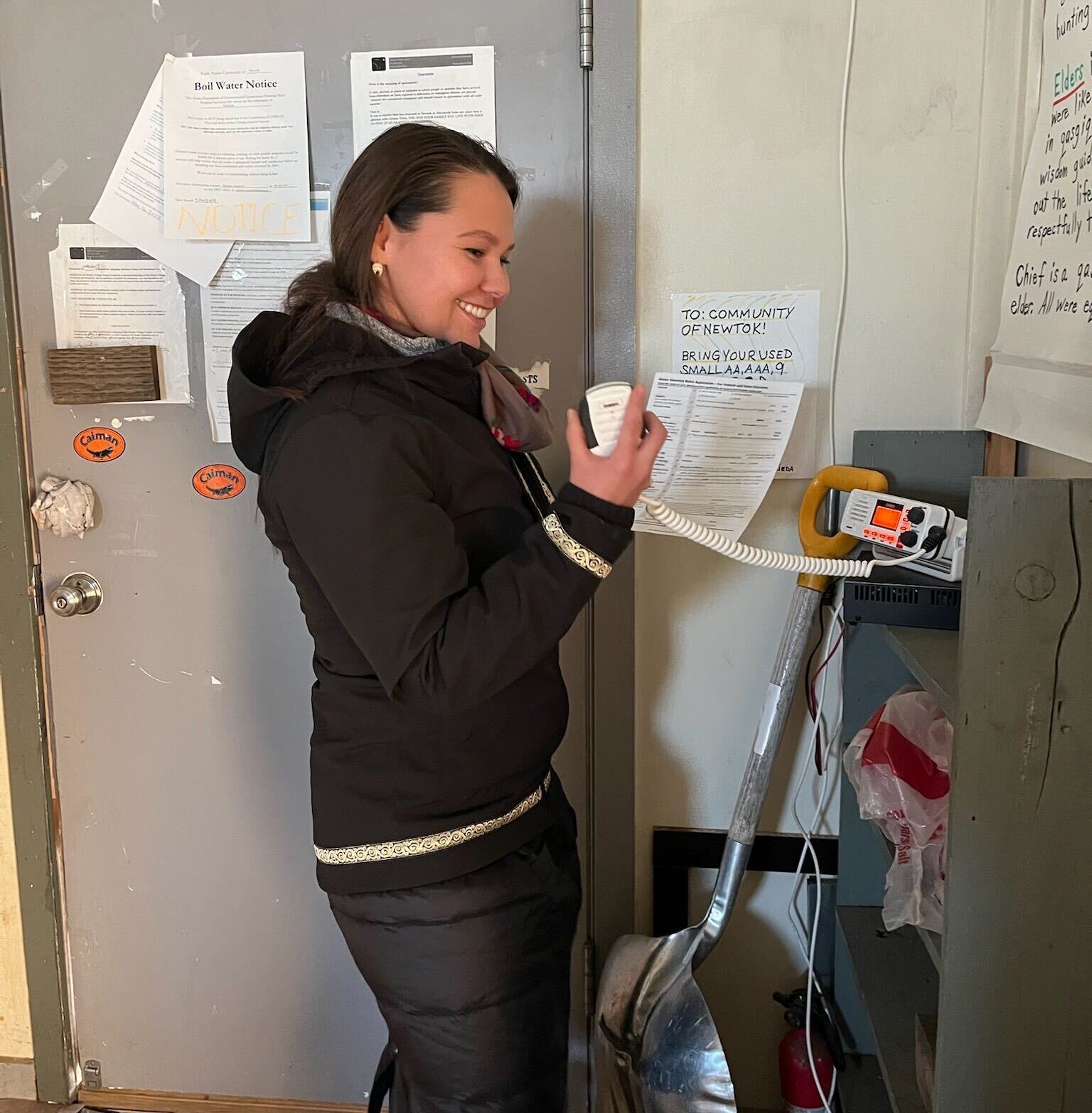

The window of opportunity was slim: A powerful storm was rolling in that would shut down air travel for a week. Jackie Boyer, a volunteer with the Mobilization Center’s Rural and Indigenous Outreach Program, a private organization, flew on a small plane to the village the day before the election to help find a way for Newtok residents to vote. She worked with the Alaska Division of Elections to request a vote-by-fax process and then spent hours setting up a printer for the ballots and troubleshooting connectivity issues.

She sent out messages through the VHF radio system that most households in the Bush rely on to inform the community that they would be able to cast their votes.

Fifty-five people ended up voting on Measure 2 in the Newtok precinct, which also includes another village across the river. The ‘no’ won handily: 18 people voted in favor of repealing open primaries and ranked-choice voting, while 37 people voted against it.

“We’ve dealt with issues like this in multiple years. And as climate change furthers and storms become more prevalent, there are more delays with mail and with planes coming in,” said Boyer. “It highlights the unique nature of Alaska and voting in rural areas. It takes a community to get this done.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.