Pittsburgh’s Most Heavily Imprisoned Areas Want Change. Will the Suburbs Listen?

In Allegheny County’s DA race in May, public defender Matt Dugan is challenging incumbent Stephen Zappala, who held on four years ago by romping in areas that see little incarceration.

| April 14, 2023

Terrell Johnson has forgotten how old he is. He stopped keeping track of the calendar sometime during his 18 years in prison because it reminded him of all that he was missing on the outside. He doesn’t know his own birth date anymore, and wouldn’t celebrate it, anyway, if he did.

“I’m done aging,” Johnson says, pacing one recent Sunday morning outside the duplex where he was raised, in Pittsburgh’s Hazelwood neighborhood. He says his mom built a safe, loving home here, and by a firehouse not far away, he points to where he and other kids rode bikes.

Johnson recalls that by the time he was 14, his friends in the neighborhood started “disappearing.” Hazelwood is a diverse area with a large Black population where the incarceration rate skies above most of the rest of the Pittsburgh metro. Johnson rifles through a mental list of kids he knew growing up, and can only think of one who hasn’t at some point been incarcerated or killed, or both.

Johnson himself was locked away in 1995, at 19 years old, for a murder he did not commit. He stayed in prison for nearly two decades, thanks in part to a local district attorney’s office, helmed since 1998 by Democrat Stephen Zappala, that was slow to take seriously the considerable evidence in his favor. Much of that evidence was publicized in a 2003 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette investigation, but Johnson would still be forced to wait another nine years for exoneration and release from prison.

“Every year, every day of that was real,” Johnson says. “I never got to play the saxophone, the drums, stuff that I really aspired to do,” he says. “I didn’t get to go to the playground with my kids and buy them Big Wheels, bikes, and get my first jobs.”

Just like so many of his peers.

“They don’t just take us one by one. They take us by the twos and threes and the fours,” Johnson says. “They just snatch us up out of here. They can put an indictment down and get 15-20 Black men outside of their households. That’s what it is. It’s still that way.”

This kind of experience with incarceration and the criminal legal system is not common in most of the city, let alone in Allegheny County, the population center of western Pennsylvania that is made up of Pittsburgh and its suburbs. Black people account for 12 percent of county residents but roughly two-thirds of the people detained in its jails, a disparity that maps onto the geography of this intensely segregated area.

When the Prison Policy Initiative analyzed Pennsylvania’s prison population last year, it found that vast swaths of the county experienced virtually no incarceration. In most of the county, the imprisonment rate was no more than six residents out of 10,000, often much less, which is far below statewide and national numbers.

But the imprisonment rate was much higher in some areas, up to 25 times that rate. In raw numbers, this means that most of the county’s population lived in census tracts from which no more than three people were imprisoned, while in some dozens of people were missing.

The four Pittsburgh neighborhoods where this is most pronounced, according to PPI’s report—Homewood North, Marshall-Shadeland, Larimer, and Beltzhoover—are all majority-Black. So, too, are a handful of suburbs with comparably extreme imprisonment rates. Emily Widra, who co-authored the PPI report, told Bolts that its alarmingly high numbers don’t even include people in jail, in the juvenile system, on parole or probation, or involuntarily confined for mental health reasons. “I think it’s safe to say that is a vast underestimate of how many people feel the burden of the criminal legal system,” she said. “Which is kind of bonkers.”

Summer Lee, who became the first Black woman representing Pennsylvania in Congress after winning an Allegheny-based House seat last year, was raised in one of those suburban areas, in North Braddock, just outside city limits and north of the Monongahela River.

“These communities are over-policed, which means they’re over-incarcerated,” Lee told Bolts earlier this month. “These folks aren’t criminals because they’re Black or because they’re poor. They’re criminals because our policies have failed them. I don’t even want to say they’re criminals; they’ve committed things that we call ‘crime.’”

For Lee and others in Allegheny County who are hoping to unwind mass incarceration, a big share of the responsibility rests on the shoulders of Zappala, who has overseen charging and prosecutions in the county as its local DA for more than two decades.

Zappala has repeatedly faced criticism from reform advocates for decisions that have favored white people over Black people and systems of power over the vulnerable. He says he holds police accountable but has seldom prosecuted officers; in one 2010 case, he declined to file charges against a group of white officers who brutalized an unarmed Black teenager. He boasts of a modern approach to substance-use issues, but in one year alone, The Appeal found, he prosecuted nearly 2,000 low-level drug possession cases. Another Appeal investigation revealed that, in 2016 and 2017, the vast majority of children who his office charged as adults were Black. Two years ago, he instructed his staff to offer no plea deals to the clients of a local Black attorney known for seeking out racial justice.

As Zappala runs for a seventh term next month, many of his critics, including Lee, have rallied around his challenger, Matt Dugan, the county’s chief public defender. (The two are set to face off in the Democratic primary on May 16.)

But the county’s segregated geography is also shaping its electoral dynamics. Zappala’s opponents must contend with different areas’ vastly contrasting familiarities with the carceral system.

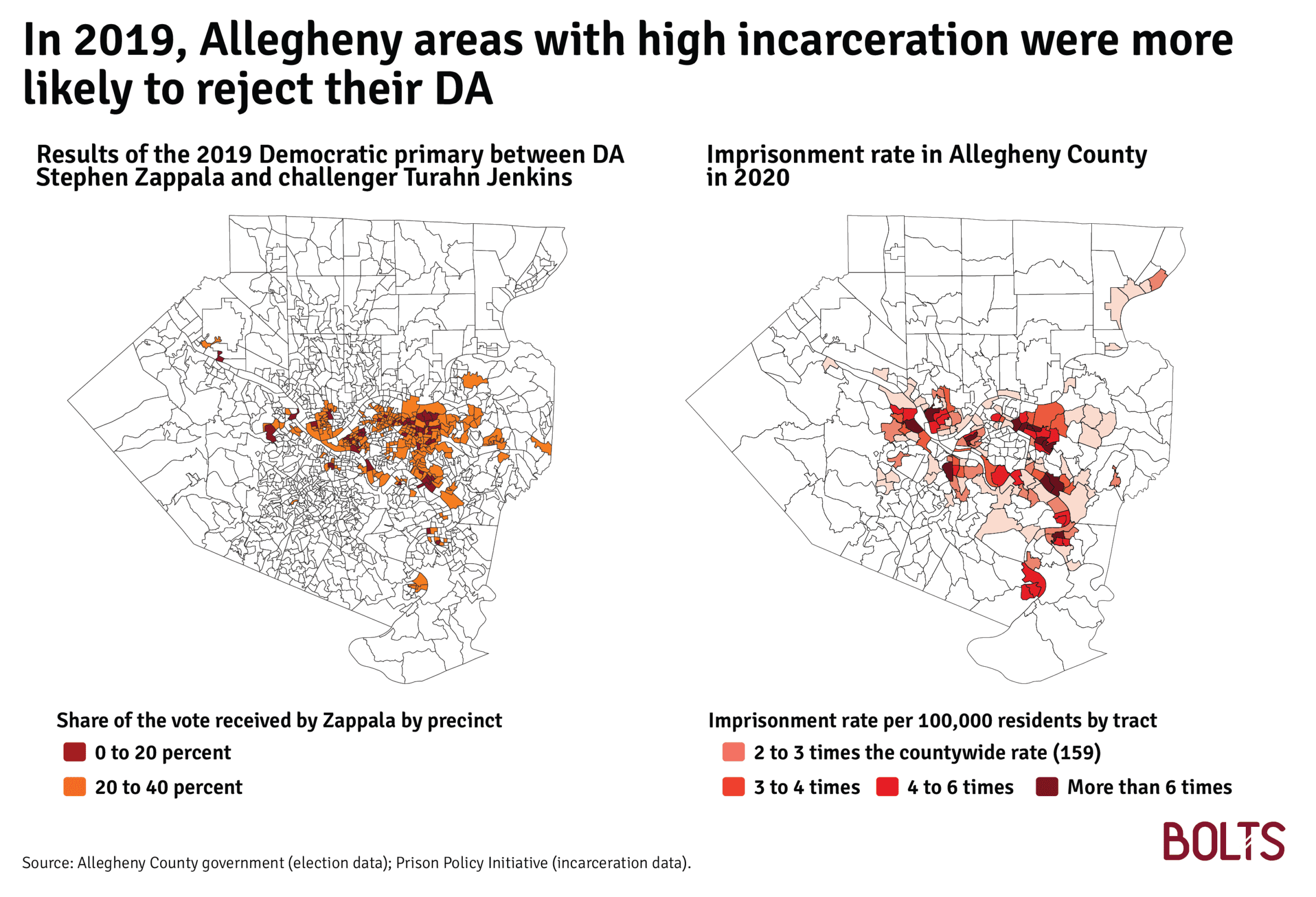

In 2019, when Zappala last ran for re-election and faced reform proponents in both the Democratic primary and general election, the parts of Allegheny County that most acutely feel the weight of the criminal legal system overwhelmingly voted against him. But they were outvoted by areas with far less experience of incarceration.

His challengers in each of the two races—a pair of public defenders, Turahn Jenkins in the Democratic primary and independent Lisa Middleman in the general—carried the city of Pittsburgh itself. They did particularly well in neighborhoods with higher incarceration, a Bolts analysis of the precinct results finds.

These areas also have especially personal investment in discussion of safety and crime, as they suffer the bulk of gun violence in the county. Homicides are very rare in most of Allegheny, but the recent tally is in the dozens in a slew of communities including Homewood, Beltzhoover, and North Braddock.

But Jenkins and Middleman both lost badly in the outlying county and fell short overall.

Zappala, meanwhile, got well under 40 percent of the vote in some areas, even in the Democratic primary when he won nearly 60 percent countywide; in some precincts, he hovered around 10 percent. But he did far better in areas with near-nil imprisonment rates and hardly lost any precinct along the outer ring of the county.

People in Pennsylvania cannot vote while they are in prison over a felony, skewing political influence even further in favor of areas from which few are imprisoned.

Dugan is aware of these geographic headwinds as he runs to unseat Zappala. The challenger seeks to harness the appetite for reform that already exists in Pittsburgh and select other pockets while also bringing in more suburban voters.

“Voters in the county are going to outproduce voters in the city by about 2.5 to one. That’s what we project,” he told Bolts about the May primary. “Our path to victory exists in the margins of the suburbs.”

One weekend earlier this month, Dugan spoke at a candidate forum inside a unitarian church in the well-to-do suburb of Mt. Lebanon, in a precinct that Zappala won by more than 20 percentage points four years ago. The next day, Dugan appeared at another forum organized by a Democratic club in the city of Pittsburgh, at a large municipal park surrounded by precincts Zappala lost badly in 2019. Zappala skipped both events.

“We have heat spots in the county where we know we have issues with gun violence, we have neighborhoods plagued by that,” Dugan said at the Mt. Lebanon event. “These neighborhoods share certain characteristics: income levels well below the state level, underperforming schools, lack of access to resources, food deserts.”

“We can do something potentially to disrupt this cycle,” he continued.

But attendee Joanie Forin, a retired suburbanite, warns that the conversation remains abstract for many in the community.

“In the suburbs, people don’t really have interaction with the criminal justice system. They just see the incumbent, and they know the name,” she told Bolts at the event. “They don’t know what happens in the jail.”

Local organizers say they’ve been working relentlessly to change that reality, including by publicizing abuses in the jail.

In 2021, voters overwhelmingly approved a popular initiative to limit the practice of solitary confinement in Allegheny County. (Jail administrators have since been accused of repeatedly violating that initiative’s mandate.) That same year, Ed Gainey became Pittsburgh’s first Black mayor, after running on a platform of racial justice. Lee won a congressional seat in 2022, after four years in the state House, while calling for jail and prison spending to be slashed, and for cash bail to be eliminated. And in February, Pittsburgh’s new city controller released an audit underscoring how the county jail thoroughly upends the lives of entire families.

Gainey has endorsed Dugan this year. So has the county Democratic Committee, an indicator of the reform movement’s increased viability among more establishment-friendly voters.

Bethany Hallam, a formerly incarcerated activist who won an at-large seat on the Allegheny County’s council in 2019 and who also supports Dugan, told Bolts that the terrain has changed significantly since her first election.

“We’ve done hundreds of these forums and Democratic committee meetings and at all these places,” she said, “you hear it over and over again: every single place, people ask about the jail, about the legal system. And that never happened. Even when we had all of these exact same races running in 2019, nobody was talking about it.”

Zappala, meanwhile, still carries himself with an air of invincibility.

Some of it is that he has rarely had to fight to keep his job. Between 1999, when he first faced voters as an appointed DA, and 2019, he faced zero challengers—that’s four re-election races when he was unopposed. (This is common: 35 of 49 Pennsylvania district attorney elections this year feature only one candidate.) When he ran in 2019, facing his first challenge in 20 years, he scoffed at his critics, telling the Post-Gazette, “I’m done with socialists and ACLU forums.”

This year, local Democratic politicos say he’s nowhere to be found on the countywide circuit of meet-and-greets and candidate forums. His campaign site features no policy stances as of publication.

Zappala declined to be interviewed for this story and a spokesperson did not respond to a follow-up with written questions. He also did not show up at either of the candidate forums that Bolts attended.

Lee, who has called for Zappala’s removal for years, finds it troubling that the areas most punished by his office don’t get to communicate with him more. “Those very same communities that are underinvested, basically carrying the brunt of the injustice, are also the communities that are least likely to even have candidates talking to them in the first place,” she says. “Zappala isn’t coming to these communities to get votes, he’s not interacting with them on the front end.”

Reform proponents are quick to remind that these are the same places most challenged by poverty and underfunded public education. But for Zappala, this confluence of factors is a reason to eschew criminal justice reforms rather than embrace them.

By the time someone comes in contact with his office, he has said in past interviews, so many problems—lack of access to affordable health care and housing, for example—are so baked-in that it’s unfair to call his record classist or racist. And it’s unreasonable to expect a DA’s office to take those considerations into account.

“I’m not in charge of transportation, safe and decent housing, or education,” he said in 2019. “I’m on the back end of government.”

Zappala has stressed that his office simply takes each individual case as it comes. “It’s a reality: an officer brings a case in and they say, ‘Here are the facts,’” he said at a forum four years ago when pressed about racial disparities in the county jail. “We ask, ‘What is the evidence that supports what you’re saying is fact?’ And then we charge based on that evidence.”

Frank Walker, who leads the Pittsburgh Black Lawyers Alliance, said in an interview with Bolts that he finds it “absurd” that a person in such a powerful position speaks as though he has little agency over outcomes in the local legal system. “If you can’t contribute,” Walker said, “why are you even there? Then what’s your job? If it’s making people safe and making sure justice is undone, it would appear this is an injustice.” (Walker emphasized that he was speaking for himself, not the Alliance.)

Even as he has occasionally touted some programs to alleviate incarceration, Zappala has largely maintained a “tough-on-crime” persona, even as Democratic prosecutors in many parts of the country have of late tended toward less punitive action, particularly in lower-level cases.

Local defense attorney Paul Jubas, who has handled a string of high-profile cases in Pennsylvania, drew a stark contrast between Democrats like Zappala and Philadelphia’s reform-minded district attorney, Larry Krasner. Jubas, who has deep knowledge of both offices, said, “It’s quite a different experience working on a post-conviction case in Philadelphia and working on a post-conviction case—or any case—here. They cooperate in Philadelphia. They’re interested in doing justice. … This district attorney, he’s not exactly engaged. And he hasn’t been for a while.”

Terrell Johnson was one of those post-conviction cases that landed on Zappala’s docket after he became DA in 1998.

Zappala didn’t prosecute Johnson, but his office did help keep him incarcerated. According to court records, his staff spent five years, starting in 2007, reinvestigating the case, then produced just a six-page report. All those years, the critical evidence that would eventually exonerate Johnson was available to them.

Johnson’s lawyer during the retrial was Turahn Jenkins, who later became Zappala’s challenger in the 2019 Democratic primary. Jenkins declined to comment for this story, but Walker, who shared an office with Jenkins and watched the Johnson case closely, faults Zappala’s office for its focus on maintaining Johnson’s conviction. “They could have actually investigated the case properly, with a mindset of seeking justice,” he said. “They could have sent it to the conviction integrity unit, they could have made a referral to the attorney general’s office. But that office will always put self-preservation over everything.”

In 2019, by then free for seven years, Johnson saw Zappala at a campaign event, and thought he’d introduce himself. His hands were shaking: before him stood a man who at one point held enormous sway over whether Johnson would die in prison. He approached Zappala, who, he said, didn’t seem to recognize him.

“I said, ‘You really don’t know who I am, do you?’” Johnson says. “He said, ‘No.’”

Johnson saw himself as a “shining star” coming out of incarceration, a rare success story among the wrongly convicted. “This stuff doesn’t happen,” he told Bolts. “I die in jail. That’s my outcome.” Surely, Johnson felt, Zappala would recognize one of only nine people ever exonerated from Allegheny County during his long tenure.

“I just stood there and looked at him,” Johnson said. “He moved on to his next conversation.”

Dugan promises to create a new role in the office dedicated specifically to investigation of past convictions, so that innocent people, like Johnson, as well as the many more people he believes have been overcharged, can be freed.

Still, when it comes to outlining policies that would change the county, Dugan has generally proceeded with some caution. He declines to speak in “absolutes,” saying he would never rule out prosecution of any offense–though he says he doesn’t see himself ever prosecuting certain behaviors, particularly sex work and drug possession. He believes cash bail is unfair and unethical, but he said he’d still seek it in some cases.

Asked at a recent event whether he’d ever seek the death penalty, he declined to altogether rule it out, as other DA candidates have done, saying it should be reserved for only the most extreme situations.

But Dugan is enjoying strong support from Zappala’s critics, who see in him an opportunity to turn the page. To differentiate himself from the incumbent, Dugan says he would move people out of the system and into diversion programs even if they don’t plead guilty. He promises never to pile a case on someone just because he can. And he says he will seek shorter supervision periods, an important issue in a state that has among the nation’s highest rates of people who are kept under probation and parole. He believes this will help bring down the population of the jail, which is filled with people dinged for allegedly breaking the conditions of their supervision.

“It’s about thinking differently about the role of the district attorney in the criminal justice system,” Dugan told Bolts. “This isn’t serving the individuals well and it isn’t serving the county well.”

The confrontation between Zappala and Dugan could extend well beyond May 16. While Zappala filed to run as a Democrat, there are efforts among local Republicans to qualify him to be the Republican nominee via write-ins. (A similar effort succeeded in 2019, and Zappala accepted the GOP’s nod, eventually running in the general election as the nominee for both major parties.) Should he lose the Democratic primary to Dugan in May, Zappala would only need about 500 GOP write-in votes to become the Republican nominee and run against him again in November, according to TribLive.

For local organizer Tanisha Long of the Pennsylvania-based Abolitionist Law Center, the election is the culmination of years of education and activism to build a case for systemic overhaul. Long charts some wins so far—the passage of the anti-solitary confinement ballot measure, for one, and the fact that once-sleepy meetings of the county Jail Oversight Board are now better-attended and closely-watched events.

Still, Long worries the message may not have sufficiently taken hold in all parts of the county.

“A lot of groundwork was done to get the public to understand what was going on. I think that four years ago, people who weren’t activists had no idea, and they didn’t know who had power over such things,” she said. “Now we are saying as activists, ‘We’ve brought all this to your attention. What are you going to do about it?’”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Pennsylvania Votes

Bolts is closely covering the ramifications of Pennsylvania‘s 2023 elections for voting rights and criminal justice.

Explore our coverage of the elections in the run-up to the May 16 primaries.