He Was Convicted Entirely On Clashing Eyewitness Testimony. Alabama Plans to Execute Him Next Week.

No physical evidence connected Anthony Boyd to a 1993 murder. He was sent to death row on the word of a co-defendant who testified under the threat of capital punishment.

| October 15, 2025

On the afternoon of August 1, 1993, the Talladega County Sheriff’s Department got a call to check out the ballfields in Munford, Alabama. When they arrived, they discovered a man’s badly burned body lying underneath an oak tree where spectators would sit to watch softball games. A pair of cinderblocks were nearby, and a charred wooden board was next to him.

Unable to identify the body, the state’s forensic pathologist cut off a hand during the autopsy in order to take fingerprints. They came back as a match for Gregory “New York” Huguley, 32, who lived in Anniston, about 20 minutes north of Munford.

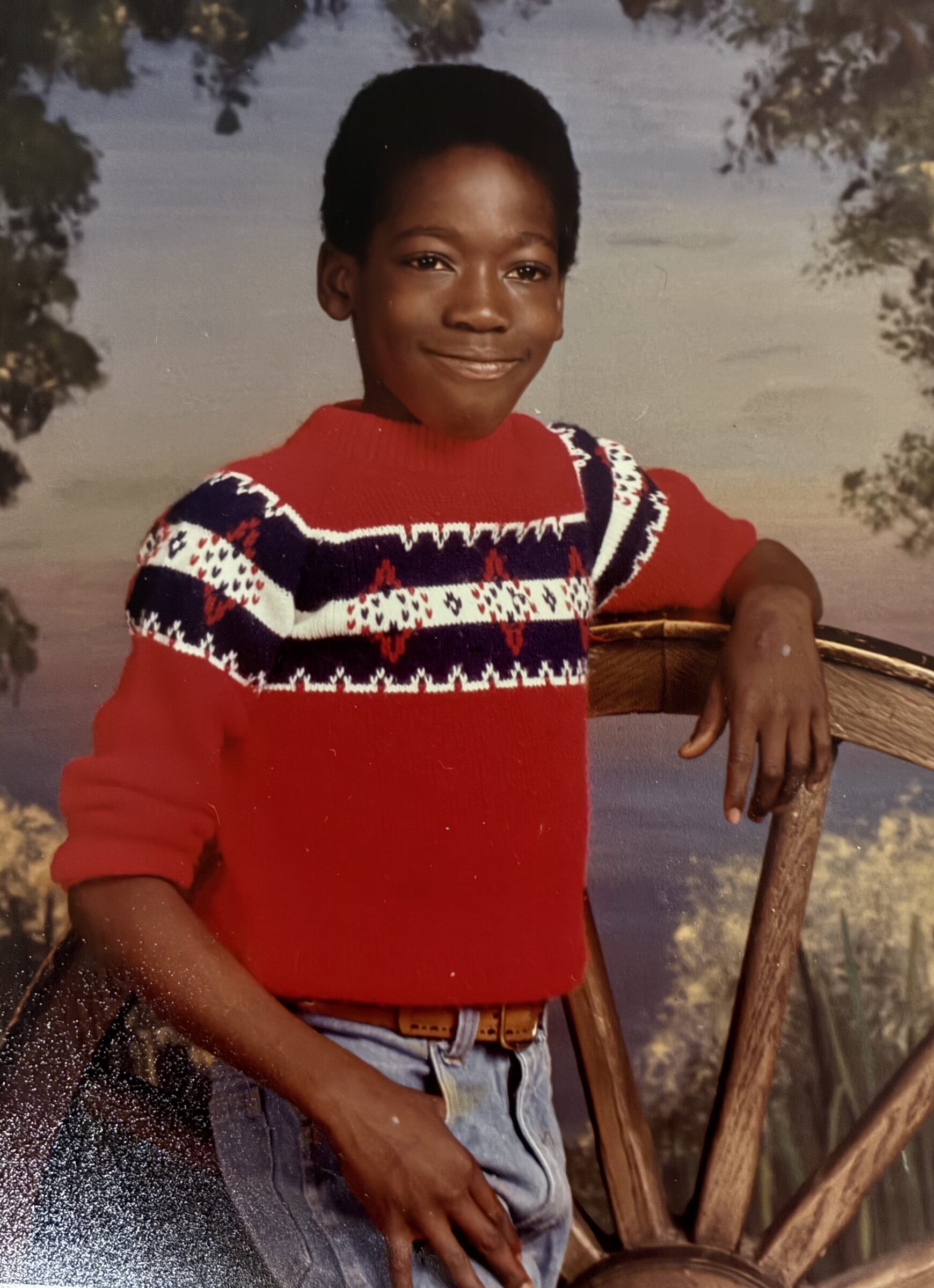

The following month, Maurice Boyd, who was in the third grade at the time, returned home from school to find his mother sitting at the counter frantically trying to track down his older brother, Anthony Boyd. Officers from the Talladega County Sheriff’s Department had visited their house looking to ask him some questions. After Anthony returned home from walking their dog, a rottweiler named Secret, he headed back out to talk with police, as his mother begged him not to go. Maurice remembered Anthony reassuring her that there was nothing to worry about because he didn’t have anything to hide.

“That was the last time he was around,” Maurice, now 42, told me. Soon after, he learned that his brother Anthony, along with three of his friends—Shawn Ingram, Moneek Marcell Ackles, and Dwinaune Quintay Cox—had been arrested for Huguley’s death.

Prosecutors sought the death penalty for Anthony, charging that he didn’t kill Huguley but was equally culpable because he was an accomplice. Anthony maintained that he had no involvement in Huguley’s death.

Facing the threat of the electric chair, one of the men, Cox, struck a deal with prosecutors to testify against his co-defendants in exchange for a sentence that would allow him to eventually walk free on parole. There was no physical evidence tying Anthony to the killing, and so Cox became the star witness at his capital murder trial in March 1995. Prosecutors bolstered their case with witnesses who testified to seeing the men kidnap Huguley, but whose stories clashed in significant ways. When it came time to mount Anthony’s defense, his court-appointed lawyer said that he didn’t have enough time to prepare for the case and failed to call witnesses to corroborate Anthony’s alibi. He was quickly convicted.

Sign up to our newsletter for more reporting on the death penalty

Maurice testified during the second part of the trial, when the jury was tasked with deciding whether to sentence his brother to death or spare his life with a sentence of life without the possibility of parole. He spoke about Anthony coaching him in basketball, helping him with his homework, and taking him to the movies and to Six Flags, and asked that the jury let his brother live.

At the end of the trial, which lasted just three days, Anthony was sentenced to death by a jury vote of 10–2. (Alabama and Florida are the only two states that allow death sentences to be handed down even when all jurors don’t agree.) He told The Anniston Star through tears, “I’ll maintain my innocence until the day I die, which I guess will be in the electric chair.”

After Boyd’s trial, his co-defendant Ingram was also sentenced to death, while Ackles was sentenced to life without parole. Cox, who took the stand against all of them, was freed in 2009.

This past August, Maurice was at work when he saw on social media that Alabama had set Anthony’s execution date for Oct. 23. The state is planning to execute him with nitrogen gas, an experimental method that involves suffocating prisoners to death.

“I was thrown,” Maurice said of the news. “Being boxed in a cage for the majority of your life, it kind of sends me spiraling sometimes, and now it’s a little worse to know…there’s a date, and the clock is ticking, and it’s ticking fast.”

Anthony Boyd and his co-defendants were tried in Talladega County, in the north central part of the state about an hour’s drive from Birmingham. The rural area is best known for its NASCAR racetrack and access to the Talladega National Forest, but it was also America’s death penalty capital during the 1980s and 90s. The county of around 74,000 was responsible for about 10 percent of Alabama’s death row population, and its juries and judges sentenced more people to die per capita than any other state at the time.

Leading the prosecution was then-District Attorney Robert Rumsey, a former district judge who took office in 1978. By the end of Rumsey’s tenure 20 years later, he had sent 12 people to death row. A 2001 investigation by The Birmingham Post-Herald found that half the people sent to death row from Talladega County were Black, Boyd among them. This mirrored the larger statewide trend; while Black people make up just a quarter of Alabama’s population, nearly half the people on the state’s death row are Black. In 1992, the Alabama Supreme Court found that Rumsey had illegally struck 11 out of 15 potential Black jurors in the capital murder case of a Black woman and ordered a new trial.

Boyd, unable to afford an attorney, was represented by William Willingham, who dabbled in criminal defense, juvenile work, divorce cases, and wrote up power of attorney authorizations and deeds. He’d also previously worked for Rumsey in the DA’s office for four years. In the five capital cases he later tried against Rumsey, Willingham lost all of them. He lauded his old boss in comments to the media on his prowess in death penalty cases. “It was pretty tough against him. As prosecutors go, he was one of the best,” Willingham told The Post-Herald in 2001 for its series “Talladega: Death Row Country.”

Willingham was paid just $1,000 for his work on Boyd’s case, the standard for court appointed lawyers at the time and an imbalance that judges were unsympathetic to. At one pre-trial conference, Willingham said he didn’t want to be appointed to the case because he had to prioritize better paid work. “I just didn’t have any time to prepare for it, plus it gets to be pretty much pro bono work after a certain point,” he told Judge Jerry Fielding, who was overseeing Boyd’s case.

At another hearing, Willingham learned that he would have just over a month to review discovery in the case before going to trial. When he pushed back against the short timeline, Fielding replied, “I think a month is a reasonable length of time for you to get ready.”

Boyd was 23 when the trial got underway. The prosecution said that he and his co-defendants kidnapped Huguley in a blue Astro van in Anniston in the early evening of Saturday, July 31, 1993, then drove him to Munford—where they then duct taped Huguley to a bench, doused him with gasoline, and burned him alive because he had stolen $200 worth of crack cocaine. Prosecutors said that someone else had forced Huguley into the van and lit the match to set him on fire, but argued that Boyd was complicit in Huguley’s death because he was in the van and had duct taped Huguley’s legs and feet to the bench.

Willingham’s lack of preparation was evident from the start. He hadn’t obtained the grand jury testimony a week before the trial, didn’t subpoena four witnesses, hadn’t interviewed any of the prosecutions’ witnesses, and largely relied on notes from Rumsey, his old boss, for his understanding of what they might say on the stand.

Willingham also failed to call witnesses who might have corroborated Boyd’s alibi that he was at a birthday party in Anniston and spent the night at a motel with his girlfriend when Huguley was murdered.

On the first day of the trial, Willingham told the judge that 12 of the witnesses he wanted to call were missing.

The state had its own problems getting witnesses to come to court, but unlike Willingham, it took forceful measures to get them on the stand, including rounding up some under detainers.

In his opening statement, Rumsey explained that he was able to seek the death penalty for Boyd because of the state’s felony murder law, which stipulated that Boyd was responsible for Huguley’s death even if he didn’t light the match that killed him. (Between 2009 and 2017, 83 percent of people charged with felony murder in Alabama were Black.)

“For example, in a bank robbery you’ve got three people in a car and one person sits there and drives the car and two people go in and rob the bank,” Rumsey told jurors. “The guy driving the car is just as guilty as the two that goes in.”

Joseph Embry, the state’s medical examiner and toxicologist who testified about the results of Huguley’s autopsy, said the presence of soot in Huguley’s lungs showed that he was burned alive, and there were traces of cocaine and alcohol in his system and food still in his stomach. Embry said there was evidence of duct tape on Huguley’s face and right forearm, but he didn’t note any such evidence on his legs—where prosecutors said Boyd taped him to the bench. He also said he couldn’t pinpoint Huguley’s time of death, only saying that his body, which was discovered on a Sunday afternoon, was “fresh” and consistent with dying over that weekend.

“And there’s nothing in your examination of the body or any of the findings you made which would link Anthony Boyd to causing the burns on that body is there?” Willingham asked the medical examiner.

“No, sir,” Embry replied.

Police investigators also testified that they’d lifted fingerprints from cans found near Huguley but none of them matched Boyd or his co-defendants.

Without any forensic evidence tying Boyd to the crime, the state relied on the testimony of nine witnesses, whose stories shifted and at times contradicted the facts that prosecutors had laid out.

Cox’s brother, Donique Cox, claimed during his trial testimony that Boyd had told him that “they” shot and killed Huguley, even though there was no evidence that Huguley had been shot. Under cross-examination, Donique, who was 18, said he only talked to police after his brother cut a deal with prosecutors.

Just four of the supposedly dozens of people hanging out near where Huguley was said to be abducted wound up testifying. Each story varied in significant ways—critically, whether they saw Ingram threaten Huguley with a gun or if they even saw Boyd in the van. The one witness who testified to seeing Ingram with a gun and Boyd inside the van was later contradicted by testimony from her aunt, who told jurors that she’d seen her in front of her house all day, miles away from the scene of Huguley’s abduction.

Another witness—who only testified after prosecutors obtained an arrest warrant and police searched five different houses to find and bring her to court—told jurors about hearing Boyd, Ackles, and Ingram discuss Huguley and accuse him of stealing their drugs prior to his death, though she said she couldn’t remember who said what.

During Ingram’s trial, which happened two months after Boyd’s, the same witness admitted to using crack during the time she was testifying about and was now in jail for an assault charge. Ingram’s trial also revealed how witnesses had changed their statements in key ways since first talking to police, like whether they’d even seen Ingram that day—with one man telling police during his initial statement that Ingram wasn’t there when he was shown a picture of him.

Mike McBurnett, the lead investigator on the case for the Talladega County Sheriff’s Department, told me last month that he remembered it well because of how difficult it was to find witnesses. Most were scared to talk or didn’t want to be labeled a snitch. “One of them was on probation, and I think we got his probation officer to find him for us,” he said. “I mean, none of them just jumped up.”

As police struggled to wrangle witnesses, prosecutors tried to get the co-defendants to testify against each other.

Boyd says he declined their offer of life without parole sentence in exchange for his testimony, because he believed he wouldn’t be convicted. Ingram, who initially struck a deal that would’ve given him a sentence of life with parole eligibility, backed out, even after Fielding, the judge, seemingly tried to convince him to testify. “Do you understand you are deciding your fate?” the judge asked.

When Cox also backed out of the plea deal, Fielding repeatedly reminded him that his decision could lead to him being sentenced to die in the electric chair. Even when Cox told him that he would not testify, Fielding continued to push the issue.

“You have set your life on a course that could very easily lead you to being electrocuted,” the judge said during Boyd’s trial while the jury wasn’t present.

Later that day, Cox decided he would testify after all. Under questioning, he said he’d reassessed his odds of winning his case after meeting with his aunt and grandmother back at the jail.

McBurnett, the investigator, said the threat of a death sentence played a large part in persuading him to talk. “You’re trying to always get somebody to turn against the other one,” he said. “None of them sit down and tell you the truth. You just got to get as much as you can, and then get somebody to cooperate.”

Cox was the only witness to testify about Huguley’s death at Boyd’s trial. He testified that he met up with Boyd, Ingram, and Ackles that Saturday evening, while there was still daylight but it was starting to get dark outside, to look for someone who’d robbed Boyd. After driving around with Ackles in his blue van, Cox said they spotted Huguley, who wasn’t the original target but had also stolen from Boyd. According to Cox, Ingram got out of the passenger side of the van with Cox’s gun, a MAC-11, and told him to get into the van. Cox testified that Huguley replied, “Please, don’t kill me. Just beat me.”

Cox said that Ingram then grabbed Huguley by the arm and pushed him onto the floor of the van. After that, he said that Ackles dropped him off at his car, which he then used to follow the van.

Cox testified that it was “dusk dark” once they arrived at the ballfield. He said Ingram ordered Huguley to lay down on a bench then Ackles taped Huguley’s mouth and hands, while Boyd taped his feet to the bench. According to Cox, Ingram then doused gasoline on Huguley and made a trail around him before lighting it with a match. He said they watched him burn for 10 or 15 minutes before Huguley rolled off the bench and the fire went out. After that, Cox said Boyd got into his car with him and told him, “We all in this together now.” Cox testified that he dropped off Boyd then went back to his aunt’s house, where he stayed the rest of the night.

Under questioning from Willingham, Cox admitted that a significant part of his story had changed between his initial statement to police in October 1993 and the one he gave as part of his plea deal, in late June 1994. In the first statement, for instance, he told investigators that he stayed with Ackles, Ingram, and Boyd in the van after the kidnapping and that they rode as a group to the ballfield. He later changed his story to say that he was dropped off at his car after they picked up Huguley and followed them on his own to the scene of the murder.

“But you weren’t telling the truth back in October, you saying now, when you say you were in the van the whole time?” Willingham asked.

“Right, because then in October I didn’t have an agreement,” replied Cox. “And then when I signed the agreement, [Cox’s lawyer] told me that if I testify falsely and get caught in a lie, that the agreement could be breached. So, that’s when I changed my story.”

Prosecutors said the murder happened between 7:30 and 8 o’clock that Saturday evening, but none of the witnesses who testified to seeing Huguley’s kidnapping could remember what time they saw it happen. Some said it was “dusk dark” outside, while another witness called it mid-dark but had said in his initial statement to police that he saw them after dark. (Sunset that day was at 7:46 pm.)

During Boyd’s defense, Willingham called a witness who was at the ballfields that evening around the time that Cox said Huguley was killed; the witness said that when he left at “dusk dark” there were “a lot of people still there… At least a few hundred anyway.”

The testimony suggested that there would have likely been other witnesses at the fields during the time when Boyd was said to have helped kill Huguley. Willingham did not pursue that discrepancy further, however, and called no other witnesses who were at the field.

Willingham also didn’t call William Mosley, a Munford local who had discovered Huguley’s body on that Sunday afternoon in 1993.

Mosley had told The Anniston Star that he’d discovered Huguley’s body when he got to the field around 3:40 pm on Sunday to assess conditions before the day’s game, and that Huguley was “still bleeding a little out of his head.” That would have been roughly 20 hours after the prosecution’s time of death.

Other witnesses cast doubt on Cox’s testimony, including three people who testified about seeing him and Boyd at a party late that Saturday night, even though he said he spent the entire night at his aunt’s following the murder.

In the years since, Boyd’s post conviction lawyers have said Willingham’s performance fell short of constitutional standards. For instance, they’ve said he never consulted an independent forensic expert to try and pinpoint Huguley’s time of death, which they say could have been done with testing on the cocaine, food and alcohol still in his system.

Boyd’s appellate lawyers also wrote that Willingham had failed to properly interview witnesses who would’ve corroborated Boyd’s alibi or call into question other parts of the prosecution’s narrative; for example, they say other witnesses recalled Ackles being out of town at the time Cox said they killed Huguley. They said Willingham failed to look into another prosecution witness who had a history of mental illness that could have called into question the veracity of her testimony.

And they accused prosecutors of illegally withholding records from Willingham, his original defense lawyer, including those that would have helped corroborate his alibi and showed that witnesses were offered “certain inducements” for their testimony.

In the petitions they’ve filed, Boyd’s lawyers have said the evidence they’d uncovered since their client was sent to death row would show that he couldn’t have been at the ballfields at the time Cox said Huguley was killed. But judges have refused to grant Boyd a hearing that would have given him the chance to present additional evidence, largely on the basis that his claims were either already addressed in other courts or found to be without merit.

When I spoke with Willingham in September, he dismissed the criticism of his performance as boilerplate legal arguments during capital case appeals. He also stressed the structural challenges of defending such cases at the time, saying judges then rarely approved funding for an appointed attorney to hire their own forensic expert—let alone pay them fairly for time spent on their own investigation.

“We had to pay rent, keep the lights on, those kinds of things,” he said. “So we were kind of handcuffed, and as far as resources and how much time we can spend on cases.”

Willingham told me he believes Boyd was sentenced to death because Cox got a plea deal first, which he attributes to Cox’s ability to hire a private attorney.

“It’s sometimes that the first one that can cut a deal [who] gets the benefit of either dodging a death penalty or life without parole, and that’s kind of what happened here,” Willingham said.

“It’s always seemed kind of unfair that one of them or maybe sometimes two of them may get a death sentence, and some of them get a life sentence with the possibility of parole, and some of them may get life without parole,” he said. “It seems unfair that they’re not treated all the same.”

Ingram’s appeal lawyers have continued to fight his case. In one petition they filed in federal court in 2017, Ingram’s lawyers alleged that law enforcement had coerced witnesses to testify, writing “There is also information that most of these eye-witnesses were, in fact, picked up by police during an illicit dice-game and forced to testify against Ingram through threats of prosecution.”

A federal district court denied Ingram’s petition and the witnesses’ credibility was never further investigated.

Ackles, Boyd’s co-defendant who is serving a life without parole sentence, told me he contests Cox’s account. “I have never killed anyone and the lies that were told during Anthony Boyd, Shawn Ingram, myself trials were just that, lies.”

I met Boyd in the summer of 2018, when I was working on a story about Project Hope to Abolish the Death Penalty, an anti-death penalty organization run by prisoners on death row in Alabama. I was interviewing members of the group about how they’d come to join it. Boyd, who was sergeant at arms of Project Hope, told me in a measured southern drawl that, “I didn’t even know Alabama had the death penalty. When they told me it was capital murder, I said ‘What is that? All in capital letters?’”

After joining Project Hope, Boyd says he worked to educate himself about the death penalty, and share what he was learning with the public.

“This justice system is set up for the ones who have and to keep the ones who don’t down,” he told me.

Two prisoners formed the organization in 1989 after an intellectually disabled Black man on death row, thought to be innocent, asked them for help. They put together a five-man committee to raise awareness about rampant problems with the administration of the death penalty in Alabama such as racial discrimination, misconduct, and its disparate application to poor people.

The group still meets weekly in the television room at Holman Correctional Facility, a maximum security prison in Atmore that houses the state’s death row. During the meetings, its 15 or so members talk about recent death penalty news and discuss legal strategies for their cases. The organization also publishes a quarterly newsletter, On Wings of Hope, where prisoners write about the death penalty and life on death row.

In 2018, Project Hope members learned that they only had five days to decide whether to choose to die by nitrogen over lethal injection, the method Alabama had been using and which appeared to cause long and painful deaths, drawing legal and media scrutiny. The state promised that nitrogen would be more humane than lethal injections, and that prisoners would fall unconscious within seconds. But the state did not share a protocol for how it’d use nitrogen, or give a timeline for when it expected to employ the method. Members of Project Hope spread the word for prisoners to call their attorneys so they could get advice on how to proceed.

Boyd at the time opted for nitrogen, but he says he wasn’t given enough information and that he later changed his mind. In response, the state has said that Boyd should be locked into using the method regardless.

In mid-July, his lawyers filed a challenge saying that Alabama’s plan to use nitrogen violates the Eighth Amendment’s protections against cruel and unusual punishment and that the state’s refusal to allow Boyd to see an unredacted protocol is a breach of his rights to due process. Boyd asked to be executed by either hanging, firing squad, or with drugs used for medical aid in dying.

They cited witness reports from the five nitrogen executions conducted so far in Alabama, which began using the method last year, plus one in Louisiana, which first executed a prisoner with nitrogen in March. During those executions, media, legal, and medical witnesses said that prisoners gasped for air, convulsed, and shook violently against the restraints in their final moments. (When I witnessed Alan Miller’s execution in September 2024, he thrashed and jerked on the gurney as his eyes darted back and forth.) Boyd’s lawyers argued that this showed that prisoners were subjected to “conscious suffocation, terror, and pain.”

In early September, Boyd’s team argued their case at an evidentiary hearing featuring testimony from a dozen witnesses, including journalists, lawyers, and medical experts. Deanna Smith, the wife of Kenneth Smith, the first person in the nation to be executed with nitrogen in January 2024, said that witnessing his death was like “watching somebody drown without water.” Other witnesses testified that prisoners appeared awake as they struggled to breathe for minutes.

In response, Alabama’s lawyers have pointed to Boyd’s critical writings about the nitrogen method in On Wings of Hope, Project Hope’s newsletter, as evidence that Boyd knew what he was agreeing to and is only suing now out of gamesmanship. The state has maintained that the method is working as planned and criticized his lawyers for relying on media accounts to build their case, saying that the courts have ruled they are “unreliable evidence” and “highly questionable hearsay.”

On Thursday, Emily Marks, the federal district court judge who heard the case, denied Boyd’s challenge, saying that it was filed too late and it was unlikely that he’d win based on the evidence he’d presented. In her ruling, she wrote that reports of prisoners remaining conscious for up to four minutes during their executions “are largely outside of the ADOC’s control and instead depend on the inmate’s behavior—whether voluntary or involuntary.”

Boyd has appealed his case to the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals. He’s also filed his own challenges in state and federal courts. In one, he alleges that the state has violated his rights by arbitrarily applying the death penalty while other people charged in murder-kidnapping cases received more lenient sentences.

After the state set his execution date, Boyd says he started working to tie up loose ends with Project Hope to pass on leadership to the group’s vice-chairman, Bart Johnson, and help him take over running the organization. Guards immediately moved him into solitary confinement, a policy the Alabama Department of Corrections adopted for prisoners with execution dates, and he can no longer attend the group’s meetings.

I remained in contact with Boyd after I initially spoke with him in 2018, and over the years he told me about the work he’d been doing with Project Hope, like conducting a study on racial disparities in Alabama’s death row population. He told me that he’d been involved with drugs back in Anniston and had his problems with the cops, but wasn’t involved in Huguley’s death.

In April 2019, Boyd told me that he’d been voted as chairman of Project Hope. It was a cause for celebration, and also an omen: Other members had said that the higher someone advances within the group, the closer they are to death.

Johnson told me that Boyd, who goes by “Ant”, is now “family” to him. “When difficulty arises, I always know he’s got my back,” Johnson said. “And he very much looks out for all of us here as the elder statesman who cares about and for his brothers.”

Esther Brown, Project Hope’s executive director and the only free person in the organization, told me that Boyd “has always taken care of others,” and recounted how he once helped get a prisoner moved to a different cell after he was having problems with people around him. Brown called him “the most effective chairman.”

“People know that he gives a damn about them,” she said.

Brown has protested Boyd’s pending execution since the state set a date this summer, attending demonstrations and a press conference, as well as sending out emails detailing problems with Boyd’s case to raise to Governor Kay Ivey, who will decide whether to grant Boyd clemency.

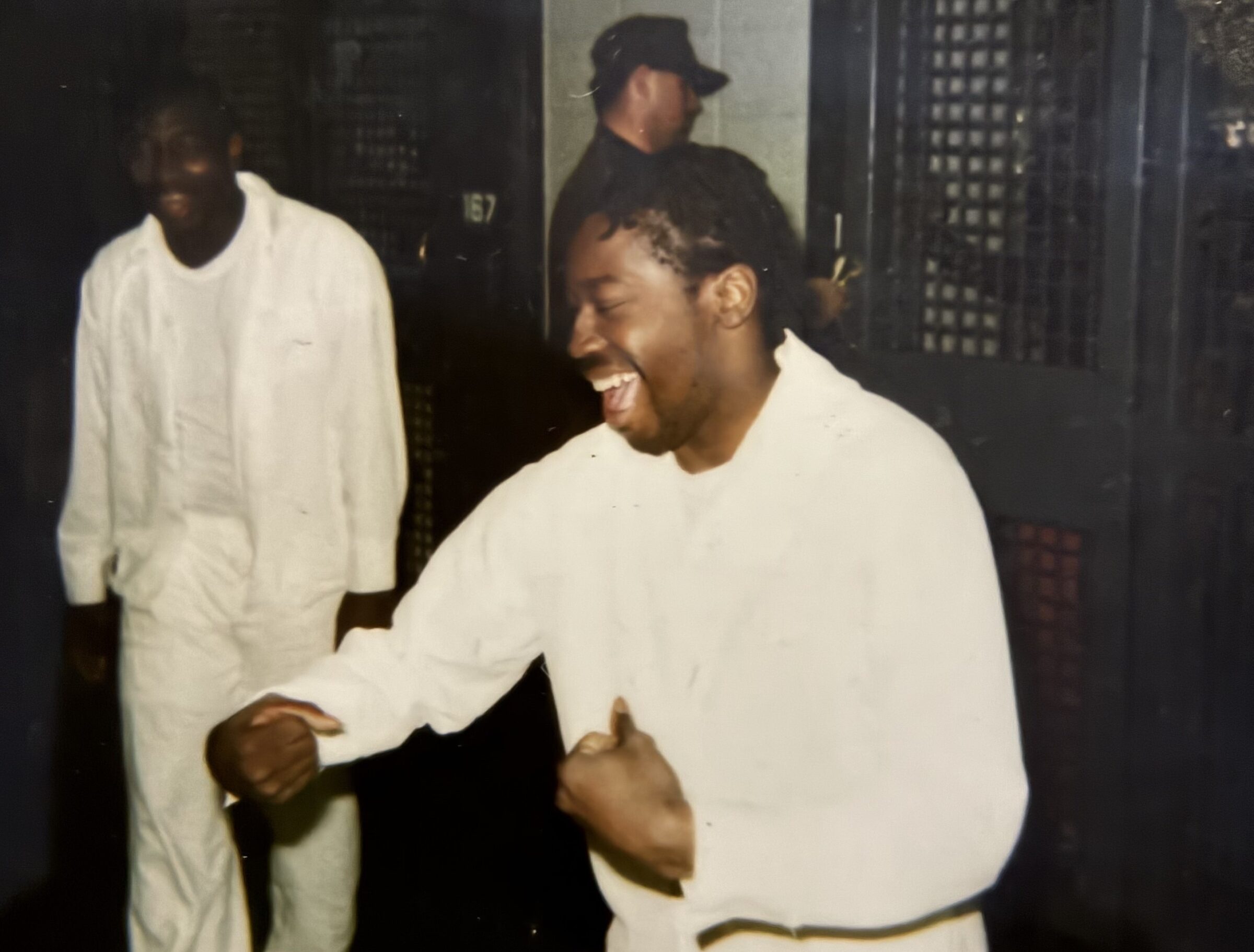

With each execution, Project Hope organizes a vigil where the men on death row dress in the formal white uniforms they typically wear when they have visitors and share memories of the person who is going to be executed.

Brown has gone through the executions of past Project Hope chairmen before: Brian Baldwin in 1999 and Darrell Grayson in 2007. Both had obtained evidence showing they were likely innocent. She was reticent about discussing the possibility that Boyd could be executed.

“How does one deal with things, you know?” she told me. “The thing is, we’re family. It sounds kind of strange or weird, but that is what we are.”

When I reached Rod Giddens, the lawyer who represented Cox at the time of Boyd’s trial, he was surprised to hear that Cox had gotten out of prison in 2009. Giddens told me that making a deal with prosecutors “was the right thing to do at the time,” and said he believed Cox had an “obligation” to tell police and prosecutors what he saw. “It certainly paid off for Cox when you’re comparing his outcome to the others,” he said. “It is striking.”

When I pointed out that the only evidence of what happened in the ballfields that weekend came from Cox, Giddens responded that prosecutors must have had more to go on. “There had to be some other evidence, because you can’t convict somebody solely on the base testimony of a co-defendant,” he said. “I just don’t remember.”

Cox declined to talk when I reached out to him for this story, telling me via text message, “Tell it like you want to tell it!”

With Boyd’s execution approaching, activists have been working to raise awareness about his case. Last month, the anti-death penalty organization, Execution Intervention Project, unveiled a billboard in Montgomery with the message, “Save Anthony Boyd.” They’ve put up an additional billboard in Talladega.

Despite his isolation, Boyd told me he spends his days as he has for the last 30 years: tackling tasks for Project Hope, working on his case, and talking and laughing with friends who stop by his cell. “This doesn’t change who I am,” he said. “This is something I’m going through.”

He said he hasn’t prepared himself for the possibility of dying by being suffocated with nitrogen gas. “There’s nothing you can do to prepare for something like that,” he said. “You can’t prepare a person for drowning.”

Boyd continues to profess his innocence and insists he wasn’t involved in Huguley’s death. “It’s easy to paint a picture when you got the paint brush in your hands,” he said of the prosecution’s case. “They painted the picture they wanted to paint.”

Though his family visits him at Holman, incarceration has taken a toll. His children have grown up, grandchildren have been born, and his father, grandmother, and great-grandmother have died while he’s been on death row. His execution is scheduled on his daughter’s birthday.

“There is no justice system in the state of Alabama,” he said. “There’s a lot of tyranny, a lot of oppression, a lot of racial profiling, racial discrimination and a lot of underhanded tricks to get what they want. What they have is a politicized injustice system.”

Last week, Boyd penned a letter for the latest edition of Project Hope’s newsletter. “This article has been a long time in the making,” he wrote. “I would love to tell all of you that I believe truth, justicе, and human dignity will prevail, but we’re in Alabama where such things are few and far between.”

Maurice Boyd said he doesn’t plan to witness his brother’s execution, should it happen. “I don’t think I can handle it,” he told me.

“We have an innocent man who has spent the majority of his life behind bars,” Maurice said. “The fight is not over and we’re gonna do everything we can to stop this and hopefully get him home.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.