Facing Arizona’s Crackdown on Homelessness, Two Cities Offer Different Responses

State intervention has led Tucson to ramp up sweeps and pass harsh new policies. Officials in the small town of South Tucson have emphasized support and services, even as they face blowback.

| August 22, 2025

This article is also available in Spanish: Leer en español.

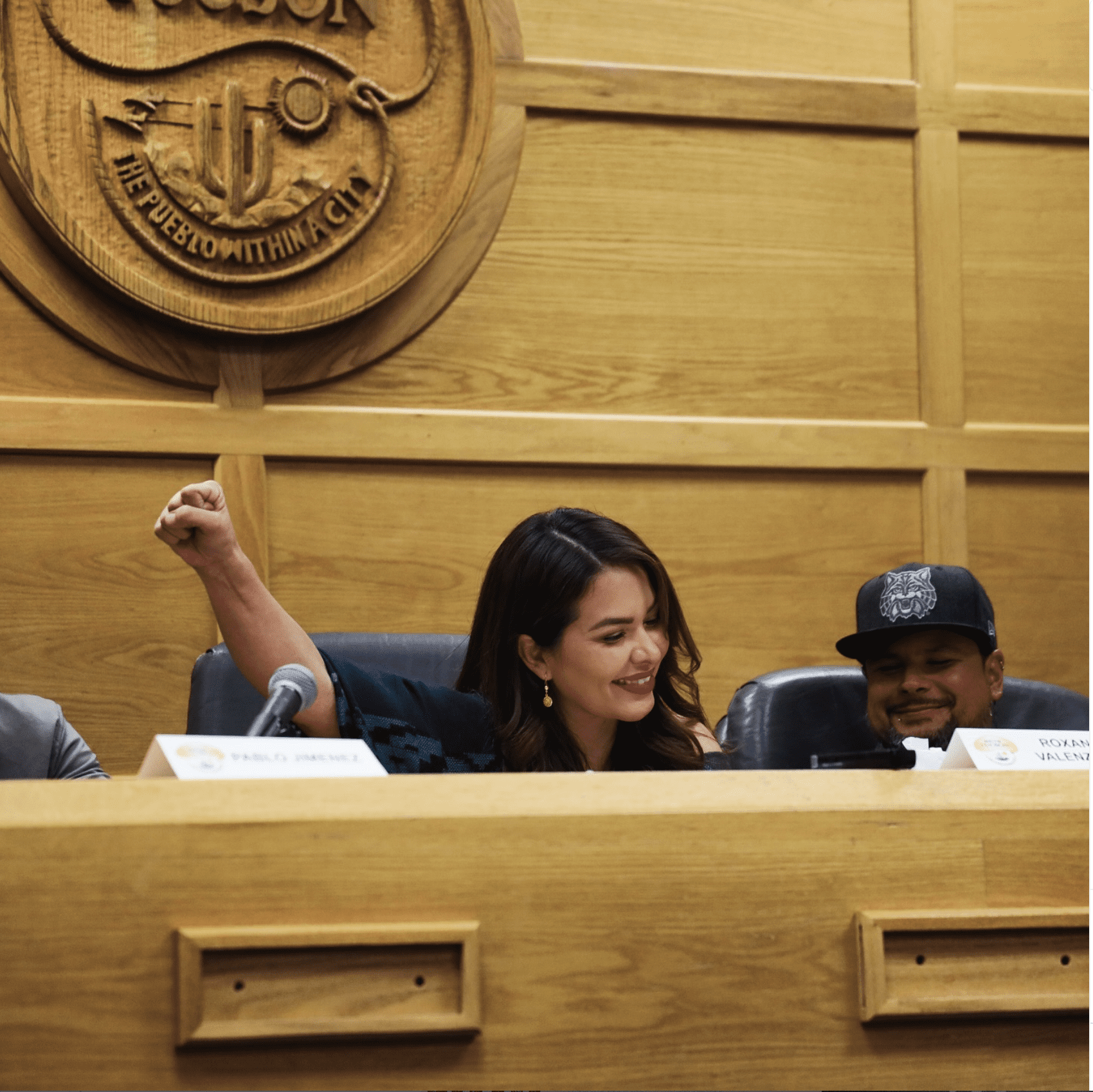

Fewer than 250 voters cast a ballot in a South Tucson recall election this month targeting the mayor and two allies in city council. The three officials, Mayor Roxy Valenzuela and council members Brian Flagg and Cesar Aguirre, form a progressive coalition in the small city’s leadership. Outside government, they also all work with Casa Maria, a local soup kitchen that provides hundreds of warm meals daily and distributes clothing, toiletries and bedding to the city’s unhoused population.

It was their deeds providing for the homeless that put a target on their back: A political rival claimed their humanitarian efforts and housing initiatives acted as a magnet for problems that the already struggling city was ill-equipped to handle.

Voters rejected that argument on Aug. 5, choosing to keep Valenzuela, Flagg, and Aguirre in office. But the recall captured the pressure that local officials as well as outreach groups like Casa Maria have found themselves under in Arizona when they respond to homelessness with anything but a punitive crackdown.

“It’s part of a bigger issue,” Aguirre told me after he survived the recall. “This country has moved so far right that it is hard to present anything humanitarian or progressive that addresses the roots of the issues. Rather than addressing poverty, they want to just lock people up and hide them away and act like the problem doesn’t exist.”

As Arizona’s homelessness crisis has worsened, local governments have simultaneously invested in various stick and carrot approaches to policy: They’ve offered some shelter and long-term housing solutions, while also conducting punitive sweeps and enforcement operations at encampments that shuffle unsheltered people back and forth between neighborhoods, city parks, and seasonal riverbeds where they can find lifesaving shade in the barren desert climate.

But as state and national leaders have ramped up the policing approach, plans to alleviate poverty and create more housing have taken a backseat; in some cases, they’ve made it a lot harder for even nonprofit organizations to engage communities and continue their aid work.

There aren’t enough shelter beds across the state—a challenge public officials admit to—but last year’s Supreme Court ruling on Grants Pass v. Johnson upheld the ability for cities to punish people for seeking shelter on public land even if there is nowhere else for them to go. The ruling freed cities to enact camping bans that target the homeless. And in Arizona, Republican lawmakers responded by advancing a policy, which was later approved by a voter referendum in November, that empowers property owners to pressure cities to more heavily police the unhoused and adopt new policies to ban them from public space.

That measure, Proposition 312, allows home and business owners to demand a property tax refund to offset the costs and damages incurred that they attribute to local governments’ failure to abate the nuisance caused by homelessness. While it is unclear what threshold cities have to meet to avoid triggering the tax refund, the law effectively allows residents to penalize cities that avoid criminal enforcement against the unhoused, while threatening to drain local coffers that fund housing and social services meant to address the issue.

In Tucson, the state’s intervention prompted the city council to amplify the sweeps it was already doing, and pass ordinances that ban panhandling in road medians and camping in parks and seasonal riverbeds, known as washes. In South Tucson, a separate city, the pressure imposed by the new state law, plus local backlash toward more progressive solutions, left the leaders who championed them on the defensive. But in the face of their political survival, they’re now doubling down on making the case for more humanitarian solutions to the housing and homelessness crises.

The small town of South Tucson is just 1.2 square miles and is completely enclosed by Tucson. The town of under 5,000 residents is predominantly low-income, and the local government has little tax revenue to invest in the housing assistance, job services and behavioral health programs that would be needed to tackle the root causes of homelessness.

Because the city doesn’t have the resources to address homelessness alone, local leaders must depend on mutual aid groups and nonprofits, including Casa Maria, to provide support like water, food, and the lifesaving overdose treatment drug, Naloxone. Those partners have also worked to create pathways out of homelessness and help relieve nuisances like garbage that are inevitable when a large population lives outdoors.

“We are not about criminalizing homelessness. We want to help them. We offer resources, even though they are limited. In a small community we are looking for ways to help them, build trust with them, and hold them accountable,” Valenzuela told me. “We are trying to piece together a coalition of groups that can help our community. We can’t do it alone.”

Valenzuela sees her work through Casa Maria as a starting point for actually solving the underlying problems causing homelessness—issues that can’t simply be shooed out of the city limits. With personal help from the council members, Casa Maria purchased two local motels in 2023 and converted them to affordable housing aimed at combating rising property taxes and rent costs driven by urban renewal in nearby downtown Tucson, which has forced many longtime residents out of their neighborhoods.

Valenzuela explained to me that she lives with her family at one of the two properties purchased by the soup kitchen. It’s an act of solidarity with other residents, she said, and also to help keep tabs on a place that used to be a trouble spot. There, she experienced for herself the challenges facing South Tucson when in July a woman jumped the fence at the hotel, urinated on the ground and began smoking fentanyl in view of her two children. As Valenzuela approached, she realized the woman looked familiar. “We went to high school together,” Valenzuela told me.

“I was able to decompress the situation. These are real people, not statistics. You need to build trust and offer them real resources. Sometimes the best people to offer those resources are not the cops — it can be a community member or a clinician,” she said.

But the tax refunds established by Prop 312 remain a looming threat to South Tucson’s already tight budget. So far few, if any, tax refunds have been issued. It is uncertain how much Arizona cities will eventually shell out to reimburse homeowners under Prop 312, and it remains unclear what kinds of policies will spare cities from triggering the penalty—but the threat alone is enough to disrupt local politics.

City Council Member Paul Diaz, a former mayor who spearheaded the recall attempt against Valenzuela and two other city councilors, criticized his colleagues for prioritizing affordable housing and aid over economic development.

Diaz has heard constituents complain of damaged fencing that would cost over a thousand dollars to replace, stolen parcels and shoplifted items, and buildings damaged by camp fires at encampments that the city may be held liable for. By making South Tucson habitable for those without homes, aid groups could inadvertently bankrupt the city, Diaz said.

“We don’t want them here, and yet we are drawing them here with the soup kitchen and low-rent housing,” Diaz told Bolts about homeless people. “Affordable housing is not a reality. It doesn’t bring money into the coffers of South Tucson for police and fire. When they started promoting affordable housing, all these people are coming into the city due to the fact that Casa Maria is affording these things that attract all these people.”

This month’s attempted recall was not South Tucson’s first: Diaz himself was recalled as mayor in 2015. He later launched a successful recall campaign in 2018 that removed the then-mayor and three council members over conflicts with the city’s police and fire departments. The latest effort, says Council Member Aguirre, is “a distraction” prompted by conservative voices on the national stage aiming to police away complex social issues that have “trickled down” and begun to reshape local governments.

Those tensions around homelessness became political fodder last election for President Donald Trump and his allies, who attacked progressive cities and Democrat-led states on the issue. Last month, Trump signed an executive order that directed agencies to pull funding from housing- first programs and prioritize federal grants to cities that enforce criminal camping bans. Despite falling crime in the capital, Trump in August declared a public safety emergency attributed to homelessness and invoked the 1973 District of Columbia Home Rule Act to federalize the Metropolitan Police and deploy the National Guard to clear encampments.

The South Tucson leaders that defeated the recall attempt, though, point their work through Casa Maria as an alternative.

They say community initiatives have also helped relieve the nuisances that might otherwise trigger the tax refund penalty created by Prop 312. Valenzuela partnered with community group Barrio Restoration to develop a project that pays unsheltered people to clean up litter, do basic landscaping, and beautify their neighborhoods. The program, Barrio Keepers, recruits people served at Casa Maria soup kitchen and allows them to develop valuable skills while improving the communities they are already part of. The program also provides housing for some keepers at the motels purchased by Casa Maria.

“I’ve struggled with addiction and with mental health. One of the things that’s helped me the most is having dignity, having something that gives me purpose and drive to want to do better,” Aguirre told me. “They might be sober for a month, or maybe just a few days, but they get put right back into the same conditions that they were in, and can’t get a job or education. Those are the things that we need to be addressing, rather than criminalizing people.”

In surrounding Tucson, even as city leaders have invested in housing and social programs, they’ve responded to Prop 312 and state officials’ push to crack down on homelessness more generally by expanding the authority police already have to remove homeless people from public land.

The city council enacted an ordinance in March that makes it a crime to stand in road medians, followed by additional policies passed in June that ban camping in parks and washes. While the bans may insulate the city from liability under the new state law, leaders said the ordinances are meant to prevent nuisances from damaging not only private property, but also the ecology of the city’s parks, seasonal waterways and nature areas where garbage, tents, bedding and needles often collect. When the bans were proposed, city manager Timothy Thomure said in a memo they are meant to prevent the loss of life during flash floods in the riverbeds and to “protect the environment.”

Before the camping bans took effect in June, police and city workers often did sweeps at encampments by enforcing laws on trespassing, drug use and other crimes, a result of mounting pressure by homeowners associations to more strictly police encampments. In a 2023 lawsuit filed by the Hedrick Acres Neighborhood Association, residents claimed the city’s failure to deal with unsheltered people living at the Navajo Wash Park had created a public safety crisis that damaged surrounding homes. An appeals court ruled in favor of the group this year and found the city can be held liable for issues tied to the encampment.

“There is a big push to appease people complaining about homelessness by putting them in jail. I don’t think they believe it, but they seem to think that going through the criminal justice system will get them off drugs and into treatment,” said Liz Casey, an organizer with the mutual aid group Community Care Tucson. “But they don’t have a plan: they don’t have new housing or group homes. [Unhoused people] go to jail, do a program, or go to detox for 24 hours, and then they’re back out on the street. There’s no plan after that.”

Casey and other advocates say that criminalizing homelessness will make it harder for mutual aid groups and city workers to connect with people living outside and build the trust with them needed to offer supplies, shelter and treatment.

In May, Tucson Police Department officers took part in an outreach event along the Santa Cruz riverbed, alongside city workers offering supportive services. The outreach operation resulted in 39 arrests, while seven people accepted assistance including housing and addiction treatment.

“That has completely eroded any trust that there was. It’s ridiculous—they had police out arresting people while they had city tents set up with chips and water for people,” Casey told me. “They know it isn’t going to help. They know it is going to make it worse. But it is to cover their own asses so they don’t get sued again.”

Kevin Dahl, the only Tucson city council member who voted against the camping bans, told me the new ordinances are unnecessary since police can already take action when an encampment creates a safety risk. The city has had a protocol in place since 2022 designed to coordinate multiple agencies to respond to complaints about encampments so that low-risk situations can be addressed through garbage cleanups and outreach instead of law enforcement. According to data from Tucson’s Department of Environmental Services, the city has done an average of 209 encampment cleanups each month this year. In July, the city slated 197 encampments for immediate removal, and 30 of those sweeps involved police. The camping bans may protect the city from legal liability and penalties under Prop 312, Dahl said, but the irony is that they are unlikely to increase policing and arrests.

“They aren’t going to result in any additional action that we are doing,” Dahl said. “Maybe some people were thinking about optics, and it looks better to the people who are concerned about encampments near them, or who have had problems with unsheltered people in their alleys or with crime.”

In the midst of the state’s push for governments to crack down on homeless encampments, a network of mutual aid groups appealed to the city of Tucson to avoid triggering the Prop 312 tax refunds by meeting the needs of the unhoused, rather than punishing them or sweeping them from one location to another. Organizers wrote an open letter calling on city leaders to invest in housing and aid as “a plea and a menu of options that already exist because of community-based organizations,” said Angel Breault, the head of Reconciliación en el Rio, a group dedicated to protecting and restoring the ecology of Tucson’s washes.

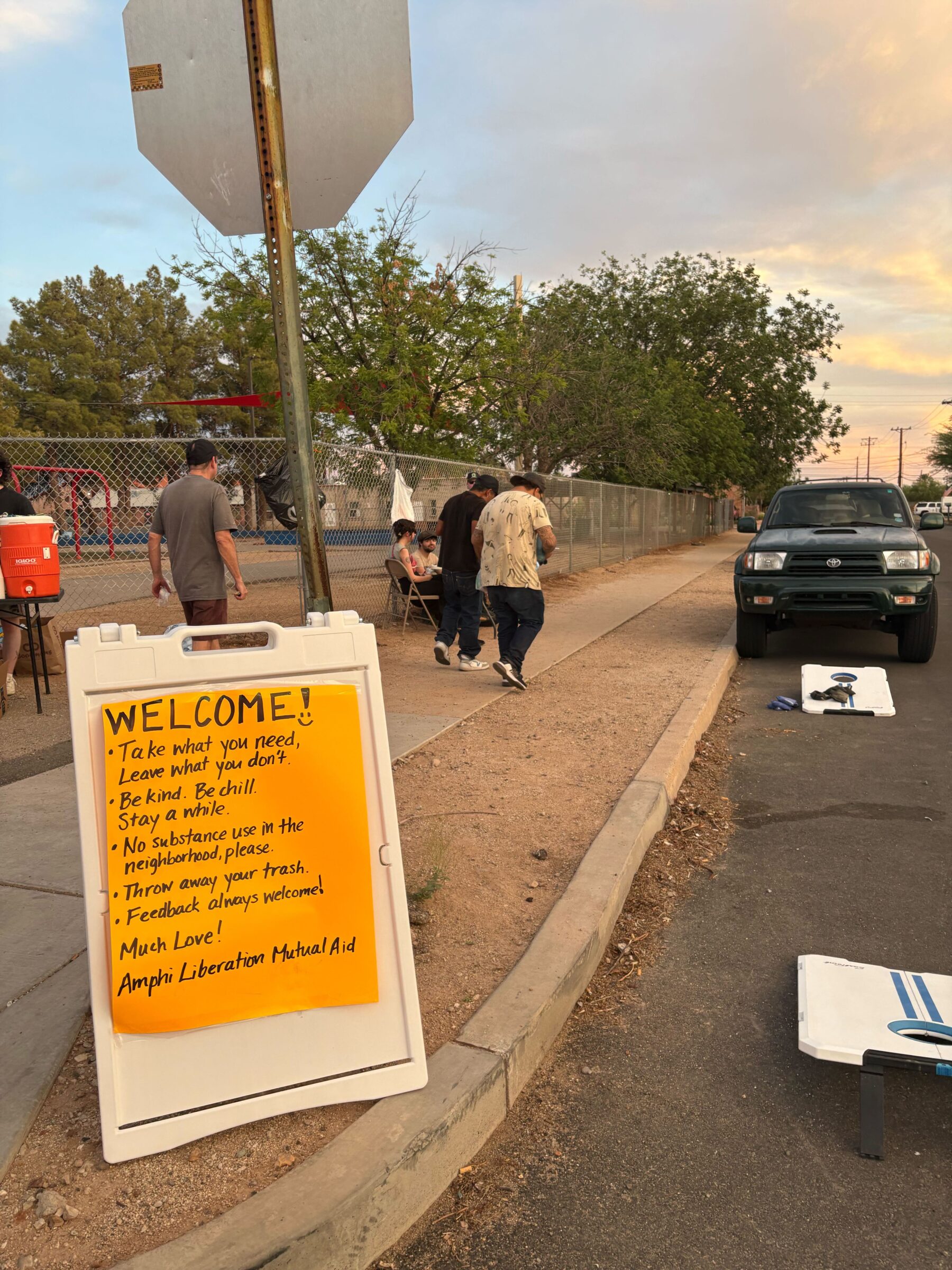

Volunteers with the Amphi Liberation Mutual Aid group set up tables with food, clothes, drinks and personal care items each week outside a fenced-off park in northern Tucson to distribute to people living in the area around sunset as the extreme heat fades.

The aid distributions are consistent, so those living in the area know when and where they can reliably restock their supplies, and most have become familiar faces, volunteers said as they set up a water cooler. Observing a distribution alongside Amphi Liberation volunteers one Tuesday, I saw that the rapport they build allows people to ask for things without fear of judgement: a young man with a cheery demeanor asked a volunteer for an extra scoop of electrolyte drink mix into his canteen before sitting down to eat. As a woman collected toiletries from a table, she asked for a spare dose of naloxone to keep on hand. The group also provides more intimate forms of care, like haircuts and wound treatment.

The church that owns the park closed it in February over maintenance issues and safety concerns attributed to those who sought shelter there. But when the park was cleared out and fenced off, it “forced these folks to scatter about the area” and lowered the turnout to the mutual aid distributions there, said organizer Xavier Martinez. The displacement caused by sweeps and park closures “really is scary” for the most vulnerable unhoused people with disabilities or chronic illnesses since it interrupts the treatment provided by nurses and other care workers at mutual aid sites, Martinez explained to me.

“If they are getting treated for a severe wound, and the next day they get displaced—that’s another prolonged amount of time where their wound begins to fester,” Martinez said. “It’s hard to be consistent with being able to treat folks.”

Tucson’s new policies may throw a wrench into the grassroots efforts to support the homeless—but with resources already stretched thin, the city also depends on those organizations to cover the gaps in services and basic necessities.

Mutual aid groups worked together to set up over 26 water stations across the city as part of the Agua Para el Pueblo initiative, according to Breault of Reconciliación en el Rio. Though neighbors are sometimes frustrated that they attract undesirable visitors, the water stations are a lifeline for preventing heat-related deaths since the city only runs a handful of dedicated cooling centers in a network of 30+ throughout the county, despite temperatures regularly in the triple digits. The water stations also provide trash bins, paper cups and sometimes reusable water bottles to cut down on trash, like the disposable gas station cups that many rely on to stay hydrated, which is the most common litter found in the washes, Breault said.

But the Agua Para el Pueblo initiative—and other aid projects—exists in a legal grey area, due to a longstanding ordinance that bars the distribution of food and drinks to 10 or more people on public land without a permit. The rule isn’t currently enforced, but it reflects the city’s reluctance to embrace the grassroots humanitarian strategies that are already in motion, even as they offer city governments a model for how they can stack resources and services to meet the needs of unhoused people while also minimizing the nuisances to neighbors.

“The groups that are being treated as opposition are the ones providing the stopgap resources that are missing,” Breault said. If the humanitarian aid they offer were to disappear, he added, “then the city is going to have a bigger problem to deal with.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.