Opposition to Mega Prison Project Shapes a Local Election in Rural Arkansas

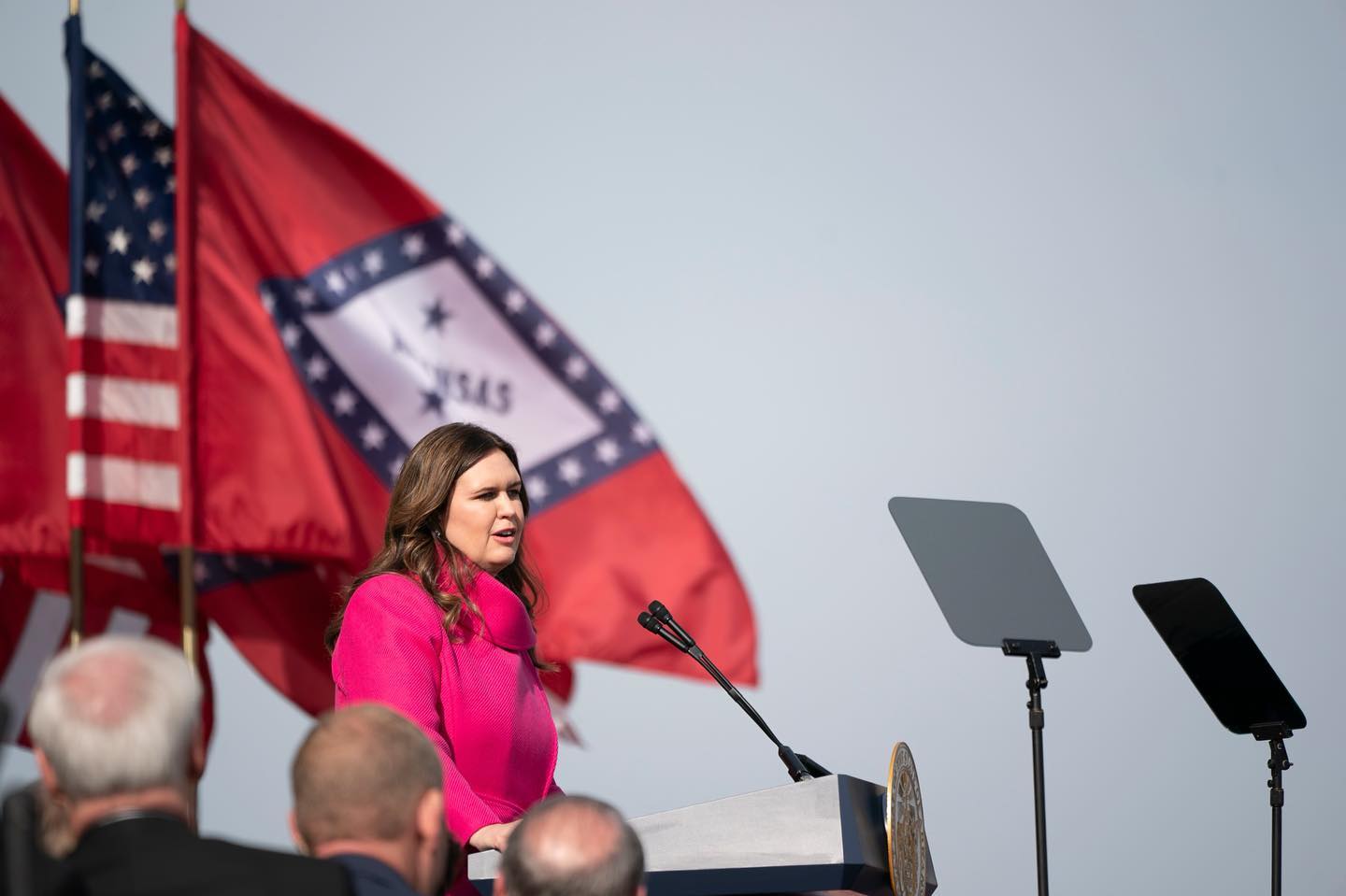

Incarceration has become a central issue in Western Arkansas, where the governor wants to build a new prison that has angered and mobilized residents.

| February 20, 2026

Before Arkansas officials announced their plan to build a 3,000-bed prison in the rural northwest corner of the state, Colt Shelby hadn’t voted in at least 15 years. Shelby, who works in the oil and gas industry and grew up in the area, says he loathes and thus largely ignored politics until 2024, when Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders revealed that the state would build the new mega prison in Franklin County, a mile from his property. As Shelby and his neighbors discovered the lengths to which Sanders and her administration had gone to hide the plan from the public, he quickly got more involved.

“I started educating myself and I had to catch up real quick,” he told Bolts.

Since then, Shelby has submitted dozens of requests for public records on the administration’s plans for the prison. Last fall, Shelby also filed a lawsuit against the Sanders administration for scheduling a special senate election to fill the seat of state Senator Gary Stubblefield, who died in September, to occur after the upcoming legislative session. The delay, Shelby said, would have robbed the district, which comprises Franklin County, of a voice in the legislature to oppose the prison.

A judge ruled in Shelby’s favor and ordered Sanders to move the election. It is scheduled for March 3.

Sanders’ plans to build a prison in Franklin County have stalled after lawmakers refused to release funding for the project over questions about costs—now estimated as more than $1 billion—and the feasibility of building a correctional facility on the rugged terrain. The legislature’s skepticism followed a public information campaign from community members of both parties who, as Bolts reported last year, banded together to interrogate Sanders’ proposal and expose problems with it. Many said that the possibility of living next door to the state’s largest prison had forced them to question the state’s primarily punitive approach to incarceration for the first time.

Subscribe to our newsletter

for more coverage of local politics and policy around mass incarceration

As a result, prisons and incarceration have become the central issue in the upcoming election. Adam Watson, an independent who has led the community fight against the facility, is running against Republican Brad Simon. Both oppose plans to build a lockup in Franklin County and support increased funding for rehabilitative programs to boost the chances that people are successful upon release. Each candidate has different ideas about reducing the need for more prison beds in the state, which regularly has one of the highest incarceration rates in the country. The district is largely made up of conservative voters.

Sarah Moore, executive director of the advocacy organization Arkansas Justice Reform Coalition, told Bolts it’s “highly unusual” for a state election to heavily focus on incarceration.

“I’m elated that we’re having very robust dialogue across communities in Arkansas who maybe historically haven’t had these conversations,” she said. “It’s been such a notable change over the last year, that in that short span of time, what would normally be a given that somebody would be very like pro build more prisons, that’s the very first thing people want to know is where you sit on the prison and it’s a non starter if you support it.”

Shelby, who is supporting Watson and recently hosted a shrimp boil in his honor, said he’s a Libertarian and has voted for Republicans and Democrats in the past. The prospect of a prison next door, he said, has made him determined to keep up with local elections.

“I never seen how it affected me,” he said. “And now I see, you know how important the school board is, how important the quorum courts are, how important the county judge position is. I mean, it is so important, and I could never stress it enough, and I’ll never miss another one.”

Prior to his death, Stubblefield was a vocal opponent of the prison project in Franklin County. Stubblefield, who since 2013 represented the more than 87,000 residents living in Senate District 26 in the western part of the state, had criticized the Sanders administration for pushing the project through without first engaging local leaders.

Watson, who moved to Arkansas from Houston a few years ago, told Bolts that running for Stubblefield’s seat was the “next logical step” after spending more than a year trying to stop the facility with his neighbors. The week after Stubblefield died last September, Watson testified at a joint legislative hearing to present findings of “impropriety and malfeasance” that local citizens had gleaned from thousands of pages of records the state had been forced to release about the project—records that showed how state officials tried to hide the project from local residents and lawmakers while also brushing aside questions about the viability of the site.

“I think when you get that entrenched in an issue, you kind of start to see all of the other things that need to be fixed in the government,” Watson told Bolts. “That’s the government overreach and the lack of transparency and the lack of accountability and corruption and cronyism and all of these things that are just these endemic problems.”

Watson said that while he doesn’t want Arkansas to build a new prison, he has come to the conclusion that the state will need to spend some money to create more beds in existing facilities since officials aren’t making efforts to reduce the prison population. (The state already pays county jails about $30 million per year to house prisoners.)

“If you’re looking at the best of both worlds, something to give the sheriffs in the counties some relief from the overcrowding, that seems like a good middle-of-the-road solution,” Watson told Bolts. “Additional significant investments need to be made in mental health, reentry programs, drug courts, pretrial services and the like to address the root causes of the crime and recidivism that have created the overcrowding issues.”

If elected, Watson would be the only independent member of the state’s GOP-run legislature.

“Look, are you happy with how your state government is functioning right now?” he asked. “And if the answer is no, then you have to understand that we’ve had a Republican supermajority legislature and governor for over a decade at this point, this is the party that bought us here. So if you want something to change, I’m giving you an option that is palatable.”

The district is deeply Republican, and Stubblefield didn’t face a Democratic challenger in his last two reelection victories. Watson says the events of the past two years—the shock of Sanders’ surprise announcement, the revelations of shoddy planning and secrecy, the escalating price tag for the prison project—have at least made his neighbors more willing to listen to opposing viewpoints.

In forums, Watson has faced questions about his views on contentious issues where he differs from many of his conservative neighbors, including when candidates for the special election were asked about their position on abortion during a February debate. Arkansas has a near total abortion ban with an exception to save a pregnant person’s life. Simon called Arkansas’ laws “pretty much perfect.”

“Whenever we start deciding who is worthy of living and who’s not worthy of living, that’s a slippery slope to go down, and I don’t think we ever need to go there,” Simon said during the debate.

Watson responded that he supports adding an exception for rape and incest and strengthening legislation to protect the health of mothers. He told the crowd, “I don’t think we can call ourselves pro-life when we’re bottom of the barrel in infant mortality, pre-term labor, maternal mortality, education and food insecurity, and on and on and on.”

Simon grew up in Senate District 26, owns a pest control company there, and is now running for the seat under the slogan, “Faith, Freedom, and Family First!” On his campaign website and in social media posts, he calls himself a “Defender of the Unborn” who supports secure borders and “safeguard(ing) Arkansas from foreign influence, particularly China.” Simon also lists the Franklin County mega prison as the number one issue facing his district.

“Crime demands tough solutions like backing law enforcement, not this secretive burden on our families,” he says on his campaign site.

Simon, who has received endorsements from Stubblefield’s brother and son, as well as Lieutenant Governor Leslie Rutledge, told Bolts that his campaign “reflects the views of our district, not only on the prison issue, but on all other issues as well.” He says his experience dealing with government overreach as a small business owner fueled his senate bid, but that Sanders’ plans for the prison had forced him to think critically about incarceration for the first time. “I know a whole lot more about it now than I ever thought I would,” he said. “Really understanding the full dynamic has been eye opening for me.”

Simon said he supports expanding existing facilities to create more bed space and alleviate pervasive overcrowding, but said the state should also still look for somewhere to build a new prison—just not in Franklin County. “I do believe that we need to find a suitable location for a new facility, or facilities,” he told Bolts. “All options need to be explored to figure out what will be fiscally responsible.”

While Simon said he wants to see more funding for mental health facilities and re-entry programs, he also told Bolts he supports the Protect Arkansas Act, a 2023 law that created the need for more prison space by significantly limiting parole and bail. “We do need stiffer penalties for criminals,” he said. “The punishment needs to fit the crime … which is why we do need more bed space.”

With Sanders expected to ask lawmakers to approve funding for the Franklin County prison when they gather for the state’s fiscal legislative session in April, the district’s next senator will have a say in the project moving forward.

Without legislative approval for a $57 million contract for an architecture and engineering firm, the project remains “in a holding pattern,” Rand Champion, communications chief for the Arkansas Department of Corrections, told Bolts in an email.

Sanders’ spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

Concerns about finding water to supply the prison remain. Leaders of nearby towns and cities have said they don’t have enough capacity to run water to the site, and two test wells the state drilled last summer barely yielded enough water to supply a house, much less a prison.

In November, the Ozark City Council voted down opening up conversations with state officials about supplying water to the prison, after passing a resolution against the project earlier in the year.

With a slew of elections coming up this year, Sanders has been backing candidates to run against lawmakers who voted against funding the new prison project last year. State Senator Ron Caldwell, who voted against funding the prison last spring, will face off against a challenger endorsed by Sanders, businessman Trey Bohannan, in the Republican primary on March 3—the same day as the special election in the 26th District.

Meanwhile, Sanders now has even more friends on the state’s Board of Corrections, which is in charge of contracts and land purchases for the prison system and has previously clashed with the governor over her plans to expand prison capacity in the state.

Sanders publicly attacked the corrections board in late 2023 after it refused her administration’s request to add hundreds of prison beds to existing facilities in preparation for the Protect Arkansas Act taking effect and increasing the incarcerated population. After the Sanders administration added the beds anyway, rejecting the board’s concerns that doing so would exacerbate chronic understaffing, the board fired Sanders’ corrections secretary—fueling a legal battle with the governor over who has ultimate authority over the state’s prisons.

Since announcing the Franklin County prison in 2024, Sanders has appointed four people to the board, giving her appointees majority control. In late January, the new board voted to fire an independent attorney representing the board in its lawsuit against the governor over control of the prison system.

On New Year’s Eve, Sanders had appointed the board of correction’s new chairman, Jamie Barker, just two weeks after he stepped down as her deputy chief of staff to become a partner at Gilmore Davis Strategy Group, a powerful lobbying firm. Barker was Sanders’ second appointee to the corrections board who works for a prominent lobbying firm, drawing criticism from opponents of the prison project, including Watson and state Senator Bryan King, who represents part of Franklin County—and who called Sanders’ appointments to the board “just open, flat out political malfeasance and cronyism, maybe even corruption.”

Barker has meanwhile voiced his support for the prison on X, posting “Build the prison.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.