Beyond Crimmigration

Two new books probe the criminalization of migration and offer alternative visions for migrant justice and organizing.

| April 10, 2024

Reporting on immigration, I have often thought that there are really two borders between the U.S. and Mexico: the physical line between countries that migrants risk their lives trying to cross, and the idea that inflames the minds of American citizens.

The border itself is a site of cruelty and criminalization. Society has essentially shrugged at the deaths of migrants in the desert and the Rio Grande, the felony prosecution of humanitarians, and the spectacle of men chained to each other pleading guilty to federal crimes as a group. The courts are currently debating a Texas law, Senate Bill 4, that would allow any local law enforcement officer in the state to arrest a migrant suspected of crossing this line in the dirt.

“The border,” meanwhile, is the locus of a vexed debate over race and national identity and crime that extends far beyond the physical frontier itself. The sentiment underlying Donald Trump’s words at his 2015 campaign launch—that immigrants are “bringing crime”—is present everywhere in public debates and policy. Frenzied news coverage of immigration borrows from the playbook of crime panics past and present, falsely connecting immigration to people’s fears about public safety. Recently, new legislation has sprung up in response to these fears, like the federal Laken Riley Act, which attempted to mandate immigration detention for any undocumented person accused of theft, and vigilante groups have taken it upon themselves to police migrants.

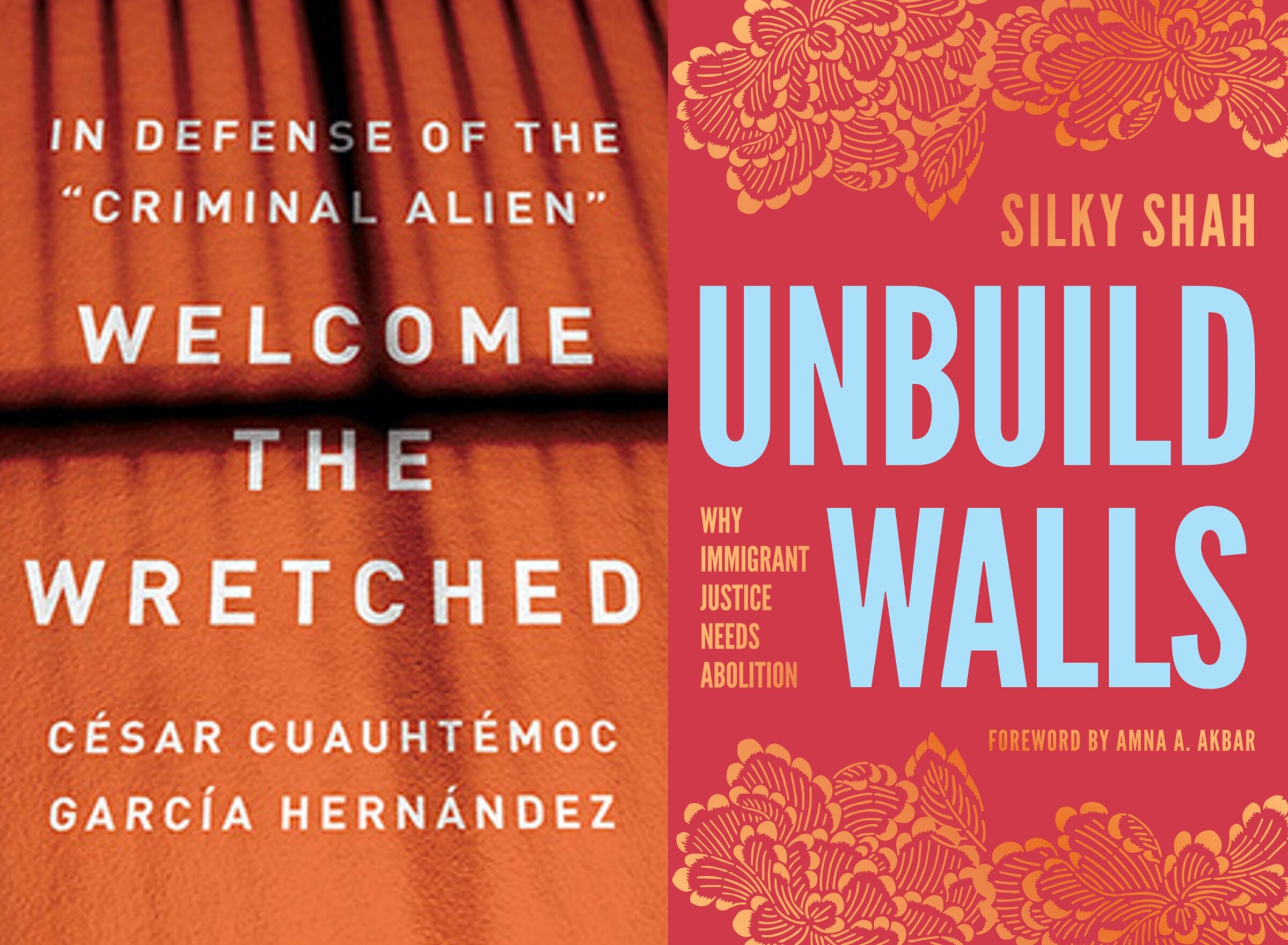

Two new books, by immigration law professor César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández and Detention Watch Network executive director Silky Shah, examine how this state of affairs came to be and provide a welcome antidote to the thinking that has produced it.

Both García Hernández’s Welcome the Wretched: In Defense of the “Criminal Alien” and Shah’s Unbuild Walls: Why Immigrant Justice Needs Abolition recount how migrants became criminalized for crossing borders, how the immigration system has come to resemble the domestic criminal legal system in its focus on enforcement and detention, and how “crimmigration,” or the confluence of these two hulking systems, effectively punishes non-citizens twice for a single crime. Both titles contain a prescription for fixing the current system (García Hernández’s is a reference to the Emma Lazarus poem inscribed on the Statue of Liberty, the one that former Trump advisor Stephen Miller famously said was “added later” in response to a question about the hypocrisy of family separation), and both texts accordingly outline bold alternative visions.

García Hernández presents a philosophical and moral case for expanding our understanding of citizenship and belonging. Recall Barack Obama’s famous speech outlining who his administration would target for deportation: “Felons, not families. Criminals, not children. Gang members, not a mom who’s working hard to provide for her kids.” García Hernández wants us to understand that there’s a lot more overlap between these supposedly opposed categories than we’d like to believe—just like there is for American citizens, too.

Drawing from the movement for prison abolition, Shah envisions a country in which no immigrant is caged or deported—ever. Reading her accounts of the sustained efforts of ordinary people to challenge the systems that confine and circumscribe their lives, I thought of the immigrants detained at Mesa Verde and Golden State Annex in Central California who last winter embarked on a month-long hunger strike, protesting forced labor, retaliation, and intolerable conditions. They weren’t just advocating for better conditions—they wanted release, full stop.

The skeptical reader might dismiss such ideas and demands as fanciful, but both texts work to convince us otherwise. García Hernández denaturalizes present conceptions of crime and citizenship, showing that the way things are now is not how they’ve always been. One surprising example he offers is a 1926 federal appellate opinion holding that it would actually be worse to deport a migrant with a record. “Deportation is to him exile, a dreadful punishment,” the judge writing the decision explained. “Such, indeed, it would be to anyone, but to one already proved to be incapable of honest living, a helpless waif in a strange land, it will be utter destruction.”

“Standing in the political moment in which we find ourselves, it’s hard—perhaps impossible—to imagine a radical reconstruction of immigration law,” García Hernández writes. “But a radical reconstruction is what gave us immigration law’s current fascination with criminal activity.”

García Hernández invokes Angela Davis and Frederick Douglass’s notion of abolition democracy as a guiding principle for the immigrants’ rights movement, but he doesn’t really show us what that might look like in practice. Shah’s book, then, is a welcome companion. Written from the perspective of a longtime activist, Unbuild Walls is grounded in the practical realities of organizing. Shah’s aim is to disrupt the notion that abolition is unserious, a purely academic gambit. On the contrary, she cites her own organizing experience and lessons from two decades and four presidents worth of immigration debates to argue that, without abolitionist principles anchoring the migrant justice movement’s strategy and demands, any attempt at change is doomed to fail.

Both authors explain how the scaffolding for crimmigration was erected bit by bit over the past century, setting the stage for a swift instrumentalization during the War on Terror. They tell the story of Coleman Blease, the South Carolina senator who succeeded in making illegal entry and reentry federal crimes in 1929, and whose racism, as García Hernández notes, was striking even in the Jim Crow South. (Blease defended lynching, decried laws that he said got “between me and the defense of the virtue of the white woman,” and, as governor of his state, pardoned a white man convicted of raping a Black woman, saying he didn’t believe such a crime were possible.)

Decades later, Blease’s law would flood federal courthouses with cases as federal prosecutors dusted off these statutes during the George W. Bush administration. By that point, the tough-on-crime era that ballooned prison populations across the country had also wholly remade immigration law. Each flagship legislative act seemed to contain a little Easter egg with grave future consequences for migrants. The 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which established sentencing disparities for crack and cocaine, also created so-called immigration detainers, or requests from immigration agents that local law enforcement officials hold someone in jail beyond their release date. An update to that law two years later, which revived the federal death penalty, additionally installed a new category of “aggravated felony” that mandated immigration detention. The 1996 Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act limited avenues for relief for the wrongfully convicted; it also expanded the category of crimes that required immigration detention to include, among others, skipping a court date. The same year, Congress passed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigration Responsibility Act, which, among other things, allowed immigration agents to partner with sheriffs to identify and deport undocumented people.

“As with so much else, where Congress and the president see a problem, police, prosecutors, and prisons are their preferred answers,” García Hernández writes.

The government’s response to 9/11 turbocharged this process, creating the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and its sub-agency, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and ramping up local law enforcement collaboration with immigration agents across the country to vastly increase deportations and detention capacity. Thanks to prosecutors’ prodigious use of the illegal entry and reentry statutes, immigration offenses would in 2004 finally eclipse drug offenses as the most common federal crime. Those statutes would provide the legal basis for the Trump administration’s infamous family separation policy in 2018.

At this point, the immigration and the criminal legal system are now so deeply intertwined that even well-intentioned efforts to sever individual points of contact between these systems can ignore or even shore up others. As many as 2,000 families separated at the border in 2018 were excluded from the class action lawsuit challenging the practice because of alleged, and in many cases specious or minor, criminal histories or gang affiliation, as I reported recently—including dozens of parents whose only crime was, in an incredible bit of crimmigration logic, violating the illegal entry and reentry statutes. (The ACLU has fought to add these families to the lawsuit, and many of them will be able to access relief under the terms of a recently finalized settlement, but only after several additional years of separation and limbo).

There are clear political hazards associated with criminality—much easier to construct a movement around the idea that the people you’re fighting for aren’t “criminals” than risk backlash for defending the rights of those who are. But Shah argues that the immigrant justice movement’s historical deference to this binary has undermined its broader goals. As Obama ramped up deportations, “many advocates argued that the problem with… the existing detention system was that innocent and vulnerable immigrants, not deserving of harsh treatment, were caught in the cross fire,” she observes. “Instead of challenging the idea of deportation as a public safety policy, the focus on ‘innocents’ threw those with criminal records under the bus, along with any critique of the criminal legal system that had deemed them disposable in the first place.”

Trump’s explicitly hardline policies on immigration, for instance, led a number of liberal states to erect “sanctuary” policies limiting local law enforcement collaboration with ICE. But many of these laws’ protections excluded people already serving prison time.

In 2021, I reported on the case of Carlos Muñoz, who was transferred to ICE after serving 29 years in a California prison for a killing he has always maintained he did not commit. Both his brothers were deported in similar circumstances, despite the fact that all three grew up in Los Angeles. Organizers tried several times to bring legislation that would fix this carve-out and ensure people like the Muñoz siblings came home to their actual community after serving their time, instead of being sent back to a country they barely remembered, but it hasn’t been successful yet. Muñoz’s case exposes a host of problems with the criminal legal system— he was a minor when the killings occurred and spent decades in prison for a possible wrongful conviction—but to some immigrants rights organizers, he was exactly the type of person who muddied their efforts to cast immigrants as tireless workers and law-abiding citizens. The problem with such a portrait, García Hernández argues, is that no one can live up to it forever.

One challenge to both arguments is that immigration policy is largely set at the federal level while in practice, those affected by it are often initially arrested by local police who share information with ICE, or ensnared in state and local criminal legal systems. The list of remedies García Hernández outlines near the book’s end—getting rid of Bleases’s statutes, which make merely crossing the border a federal crime, deleting the various provisions passed during the tough-on-crime era that funnel migrants accused of a crime into the deportation pipeline, restricting funding to DHS—are nearly all in the hands of a dysfunctional Congress. This means that for now and the foreseeable future, these solutions are near-impossible.

García Hernández acknowledges this, writing: “To be sure, none of what I’m proposing is politically possible right now. That’s the point… The time to imagine a reconstructed form of immigration law isn’t the days leading to Congress debating a bill that might garner the votes needed to land on the president’s desk. That time is now.”

Meanwhile, to Shah, the much-vaunted goal of “comprehensive immigration reform” is actually a bit of a red herring. She has watched as activists endlessly petition national lawmakers to pass legislation that ends up diluted to the point of meaninglessness or excluding entire categories of people. Instead, she argues that organizers should focus on changes that chip away at the broader system, like shutting down a detention center or ending a county’s 287(g) program—an agreement with ICE that deputizes local cops to act like immigration agents.

Shah recounts how her organization, Detention Watch Network, switched from a focus on improving detention conditions to shutting down sites entirely after observing how battles for better conditions of confinement usually just ended up expanding the system’s reach or power. Communities across the country trained their sights on their local sheriff or detention center, and succeeded in ending ICE contracts with jails everywhere from Orange County, California to Etowah County, Alabama. In 2018, a grassroots effort in North Carolina elected five sheriffs who promised an end to ICE collaboration in the state’s most populous counties.

Today, deportations are far lower than they were a decade ago, which Shah credits in large part to campaigns that took place at the local and state level. Shah observes that this kind of painstaking community organizing has eventually led presidential administrations to take notice, citing the fierce pushback against Arizona’s “show me your papers” law that eventually led Obama’s Department of Justice to successfully challenge it in court. “Winning local campaigns helps us make the case for ending immigrant incarceration altogether,” she writes.

Of course, a patchwork approach isn’t foolproof. García Hernández points out that after Oregon and Colorado passed sanctuary laws protecting immigrants’ information from ICE, the agency contracted with LexisNexis and other data brokers to access it anyway. In North Carolina, meanwhile, ICE supported legislation to force sheriffs’ cooperation.

In Louisiana, Shah notes, after the 2017 Justice Reform Initiative emptied prison beds, ICE swooped in to fill them. (Louisiana’s new governor is now seeking to further criminalize immigrants; the legislature is currently considering a law that would, like Texas’s controversial SB4, deputize any local officer to arrest someone they suspected of being undocumented.) A similar thing happened in New Jersey, only in reverse: After local organizing led to a bill that prevented future ICE contracts, counties that stopped detaining immigrants in their local lockups sought to recoup revenue by contracting to hold inmates from other counties and partnering with the U.S. Marshals Service to take some of their prisoners.

Shah writes that this is a “cautionary tale of the unintended consequences if we continue to stay siloed.” The agencies involved in immigration detention and law enforcement understand the connections between the carceral state and the immigration system from the highest levels of power to the lowest, and they know how to adapt to turn them to their advantage. In order to stand a chance, she argues, organizers who’re hoping to push back must do the same.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.