“There’s No Dignity in Giving Birth in Prison”: New Bills Would Improve Care Behind Bars

California advocates are pushing legislation that would give pregnant people in prison access to social workers and more bonding time with newborns after giving birth.

| August 13, 2024

After giving birth in 2011, Eboney Ellis says she didn’t get any time to bond with her new son. Ellis, who was incarcerated and in the custody of the California prison system, says her baby was taken away so fast that she could barely even lay eyes on him and didn’t learn the baby’s gender.

Ellis says she was given prenatal vitamins from the time she first got to prison during her pregnancy but never got access to a personal social worker she could consult if she had a question. For incarcerated women who are pregnant, social workers can be the middle person between them and an intentional start for a newborn, as they often help facilitate things like family finding, information sharing, lactation, and more. She still considered herself lucky because her family was there to pick up her baby, unlike some women whose children are quickly taken by child protective services.

“I was never able to see this child,” Ellis said. “From the moment the child was taken out, it was taken away from me.”

Ellis is now part of a coalition of advocates pushing for more humane treatment of pregnant people in California prisons. This year, they have been rallying behind proposed legislation that would mandate that people get to spend at least three days with newborns after giving birth in state prison custody—an increase from the current one to three days before removing the child and returning them to prison. Advocates say that currently, many women get little to no time with newborns after giving birth, and there is no current standard to protect and expand that time.

The proposed legislation, Assembly Bill 2740, would also codify that prison officials connect pregnant people with social workers within a week of entering prison custody or being identified as pregnant. Additionally, the bill requires prison staff to expedite the visitation process so that incarcerated mothers can have overnight visits with their newborns as soon as possible. It would also require an incarcerated mother to be permitted to breastfeed their newborn and pump breast milk to be stored and provided to the child once they’re separated.

Ellis says she is advocating for AB 2740 because it is her personal story. “It was such a horrific thing,” Ellis said. “It meant everything for me to reach back and do whatever I can to make that situation a little bit more softer, a little bit more personal.”

During a legislative hearing in late May, State Assemblymember Marie Waldron, who introduced AB 2740, said that it “recognizes the fundamental rights and health needs of women and their babies in state custody.”

“It is undeniable that prenatal and postpartum care are very important,” Waldron said during the hearing. “Reimagining outcomes of infants born in California state prisons will strengthen family bonds and reduce recidivism.”

The bill passed with unanimous approval during a May 22 floor vote in the state Assembly but has yet to clear the state Senate, which is in its final stretch of hearings before this year’s legislative session ends on Aug. 31.

As it stands, care provided to pregnant women in California prisons amounts to little more than prenatal vitamins and OB-GYN appointments, as described by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Operations Manual. De Anna Pittman, a program manager with the Young Women’s Freedom Center, which is part of the coalition pushing the reform bill, says the state needs to bolster care for people who give birth in CDCR custody. She points to research showing that a lack of bonding time and breastfeeding puts newborns at increased risk of poor health and worse developmental outcomes.

“The state of care for incarcerated pregnant people in California is not what it should be. There’s no dignity in giving birth in prison,” Pittman said. “There’s just a lot of confusion and honestly a lot of heartbreak. The process of giving birth is already a traumatic process, and to have your baby ripped away from you instantly is terrible.”

Pittman also emphasized the importance of access to social workers and expedited visitation because she says that many women could still get released while their children are young. Research shows that when incarcerated people have strong family ties, recidivism decreases.

“We want to give parents the tools that they need, so when they get out, they’re not coming back in,” Pittman said.

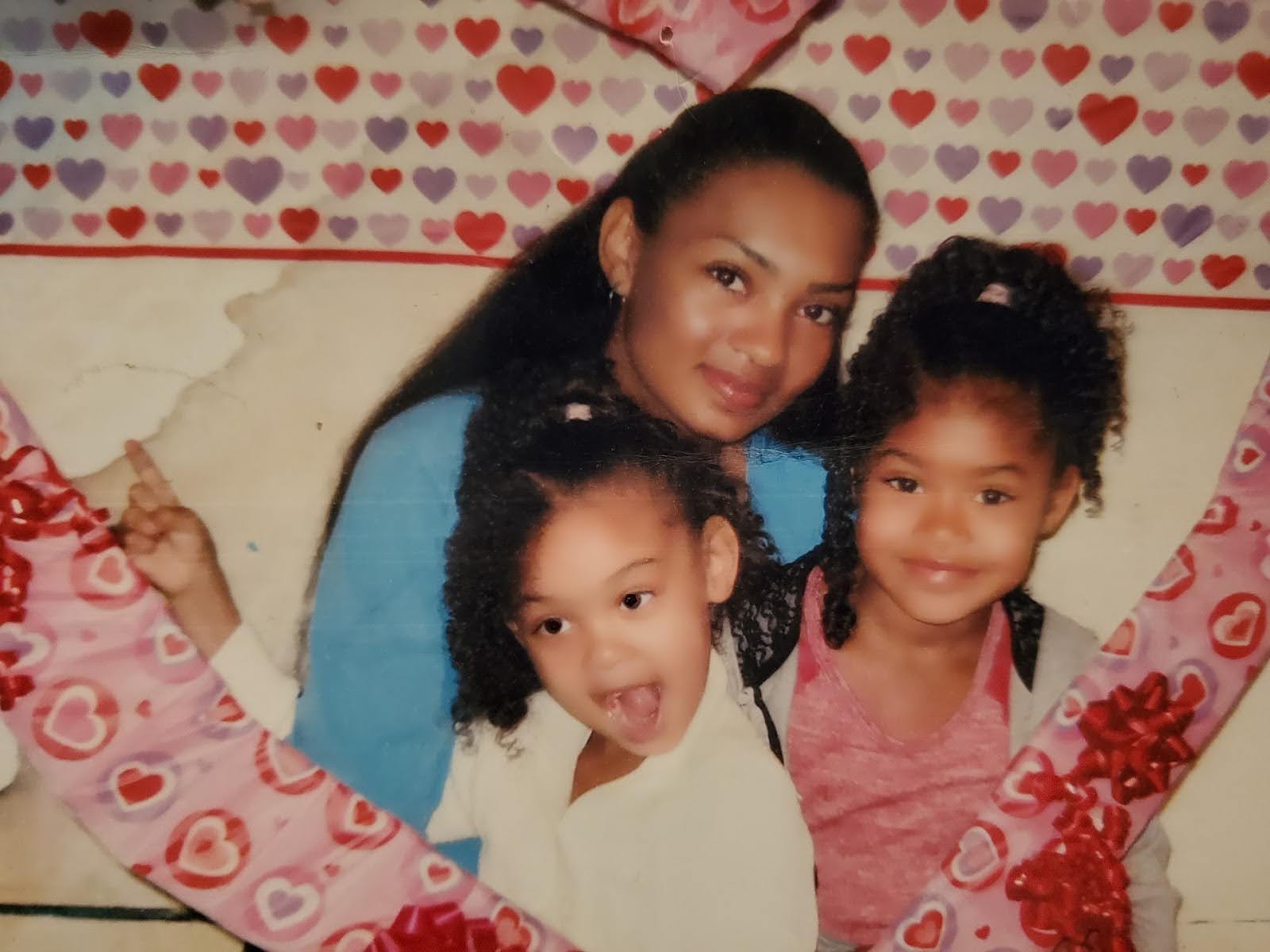

Just two days after Jonala Vann found out she was pregnant in 2011, she was sent to jail for a nonviolent probation violation. She said the care she was able to obtain while incarcerated at a Riverside County Jail in Southern California paled in comparison to the time she was pregnant with her daughter outside of prison two years prior; Vann said she was not given prenatal vitamins and was only given an ultrasound a handful of times.

Right before she went into labor, Vann had gone to a court hearing to see whether her case would go to trial or be dropped. She hoped a judge would let her go home to have her baby, but instead she was sent back to jail.

“I was really hoping just to have my daughter, even if I had to serve out my time, I just wanted to have her free,” Vann said.

After she gave birth, Vann was only given 16 hours with her baby. She said she did not sleep after childbirth because she didn’t want to miss any moments with the baby and knew they would soon be separated. She stayed up singing “You’ll Be in My Heart” from the Disney movie “Tarzan”, a song she sang to her baby all the time when pregnant, hoping her daughter could recognize her voice.

“[Those 16 hours] were really hard because I knew that I was going to have to give her up,” Vann said. “I was trying to enjoy them but at the same time I couldn’t help but feel really sad and upset that I put myself in the situation.”

It would be about seven months before Vann got to see her daughter again. She remembers the first visit as “the best and the hardest at the same time. It was nice holding my daughter and getting time to bond, but it was difficult when it came down to leaving.”

Research on pregnancy and incarceration estimates that some 55,000 pregnant people are admitted to U.S. jails every year and about 1,400 to U.S. prisons. Carolyn Sufrin, an OB-GYN who started the Pregnancy in Prison Statistics Project to advocate for reproductive justice for incarcerated people, says that treatment of pregnant people typically varies from facility to facility and that there are often barriers to the kind of care pregnant people might expect to get on the outside.

“You can’t control your own access to health care, you’re completely reliant on the facility for that. Sometimes that works out, but many times it doesn’t,” Sufrin said.

Being incarcerated while pregnant can also pose health risks. When Martha Torres was pregnant in a Los Angeles County jail, the COVID-19 pandemic was sweeping the country. She said the virus was making its way through the facility, and eventually she contracted it and was worried because she didn’t know how it would affect her pregnancy.

Torres went into jail a month and a half into her pregnancy for a probation violation. She said there were times she was not listened to when she voiced her concerns about the virus and was sometimes not allowed to take walks around the yard.

Torres was eventually able to enter an alternative incarceration during her pregnancy that allowed her to live with her newborn daughter after she gave birth so that she could bond with and breastfeed her. Torres also had another son at home who was less than a year old when she went to jail, and said it was traumatic to be separated from him and difficult to repair their bond when she got home.

“There’s a huge difference, you miss out on all your milestones, and it’s actually very traumatic for the parent and for the child,” Torres said.

This year, California lawmakers filed a series of bills aimed at improving treatment for pregnant people who are incarcerated and protecting the bonds between newborns and incarcerated mothers. One would prohibit state prisons and county jails from putting people in solitary confinement during pregnancy or for 12 weeks postpartum. Another would encourage judges to consider alternatives to incarceration for pregnant and postpartum women so they could bond with their newborns during their first year. None of the bills have yet to pass as the legislature enters its final days of this year’s session, which ends on Aug. 31.

The effort to pass new protections for pregnant people in jails and prisons follows other policy reforms at the intersection of incarceration and pregnancy in recent years. In 2020, California passed AB 732 mandating new treatment guidelines for people incarcerated in any state or county correctional facility, including transport to a hospital during childbirth and prohibitions on tasing or pepper spraying pregnant people in custody. Before that, in 2012, California passed a bill outlawing the shackling of pregnant incarcerated people, including the use of leg irons and waist chains.

Other reforms to accommodate pregnant women and new mothers in jails and prisons have hit a wall. In 2022, California Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed the California Healthy Start Act, which would have expanded a program where women in prison could live with their children to include incarcerated women regardless of the conviction type or length of their sentence. The same year, the Dignity for Incarcerated Women Act died in the state Assembly’s Appropriations Committee.

“We want to keep that mother and that baby bonded together for life so they actually get to be raised by their mothers, instead of having to believe in the system or by a grandparent,” said Tyrique Shipp, a policy fellow with the Anti-Recidivism Coalition.

Shipp pointed out the lack of oversight standards to ensure consistent physical and emotional care for the complexities of incarcerated pregnant women. Even if legislation passes that sets better baseline standards for treatment of incarcerated people during pregnancy, Shipp says more oversight is needed to ensure consistent physical and emotional care for incarcerated pregnant women, mothers and infants.

“A prison cell is no place for somebody who is pregnant or somebody after pregnancy — it’s not safe, it’s not clean — and so the focus is just trying to make sure that we can create a safe environment for these women,” Shipp said.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.