Charleston Prosecutor Candidate Wants to “Shut Off the Mass Incarceration Mindset”

In a Q&A, Ben Pogue, who is running to be the chief prosecutor of South Carolina’s Ninth Circuit, discusses how he would confront racial injustice.

| September 14, 2020

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

In a Q&A, Ben Pogue, who is running to be the chief prosecutor of South Carolina’s Ninth Circuit, discusses how he would confront racial injustice.

In and around Charleston, South Carolina, this summer of nationwide protests has compounded grievances and Black Lives Matter activism that have been building for years against racial injustice.

The protesters who gathered after George Floyd and Breonna Taylor’s deaths also remembered Walter Scott, a Black man killed by a North Charleston police officer in April 2015. Two months later, in June 2015, a white supremacist shot nine African American church-goers in Charleston.

Residents are also speaking up about the persistence of Confederate monuments at the expense of Charleston’s Black history, and against the towering inequalities of the local criminal legal system. Recent studies found African Americans likelier to be prosecuted over marijuana and to be struck from the jury pool, for instance. The state also faces litigation for suspending driver’s licenses over court debt, a practice that disproportionately affects Black South Carolinians.

Earlier this month, I talked to Ben Pogue, who is running to be the chief prosecutor of the Ninth Judicial Circuit (home to Charleston and Berkeley counties), about how he would confront these issues. He replied that we cannot confront the criminal legal system’s “systemic racism” without also addressing the region’s wider inequalities.

“If we continue thinking about justice as criminal justice, it’s not really justice,” he said.

Pogue wants to launch a “racial audit” of law enforcement that can connect the decisions made by police and prosecutors to broader socioeconomic discrepancies. Absent that comprehensive outlook, he argues, programs that are meant to divert people from conviction or incarceration are setting them up for failure. “We can come up with a prearrest diversion program,” he said, “but if we don’t know that the kid who’s involved in it doesn’t have any transportation resources, and his mom’s only transportation resource is a vehicle used for two jobs, then what are we doing?”

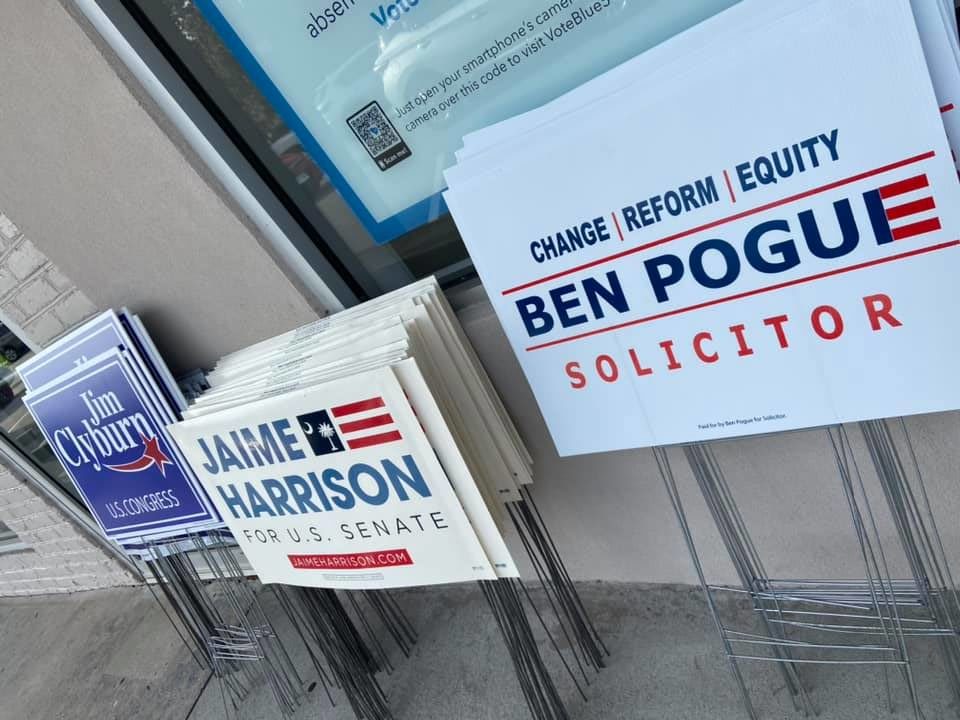

Pogue is the Democratic nominee against Solicitor Scarlett Wilson, a 13-year GOP incumbent. (Of South Carolina’s ten prosecutorial elections this November, this is the only one with more than one candidate on the ballot.) The Ninth Circuit split nearly evenly in the 2016 presidential race, and Democrats are optimistic that they can score breakthroughs in the state this fall. Jaime Harrison, the party’s nominee against U.S. Senator Lindsey Graham, tweeted in June about this prosecutor’s race that “local elections are sometimes even more important than national ones.”

In the course of my Q&A with Pogue, he stated that he would not prosecute marijuana possession, nor would he prosecute cases of driving with a suspended license. He laid out how he’d fight racial discrimination in jury selection. But he also repeatedly stressed that he would approach reform incrementally—he said for instance that he would for now treat simple drug possession as a criminal issue, despite calls to approach it as a matter of public health—invoking a need to gain community “buy-in.”

Still, Pogue was quick to delineate a stark contrast with his opponent on sentencing policies and reliance on incarceration. Asked about Wilson’s call for lawmakers to toughen the state’s “truth in sentencing” rules, which severely limit early release opportunities, Pogue answered that such a proposal is indicative of a “mass incarceration mindset” that has failed at reducing crime. Locking people up longer and making it harder for people to re-enter their communities, he added, only compounds recidivism.

“We are consistently using our current incarceration system to turn out people who have no resources to do anything but reoffend,” he said. “We’re perpetuating the depletion of the resources that a lot of times gets people in the situation where they offend to begin with.”

The Q&A has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

—

The renewed national calls for racial justice this summer resonate in the Charleston region, not just given its long history, but also due to the events of recent years. To what extent do you think the local criminal legal system has been responsive to the Black Lives Matter movement, and if elected how would your tenure advance the goals of this movement?

Our current criminal justice system has been inadequate, to say the least. Black Lives Matter should not be a controversial statement. We should be going to communities, especially communities of color, to listen, to understand what the issues are. This is of specific importance as it relates to people who look like me, people who are white folks who have lived in an environment of white privilege: We’ve got to make sure that we’re actively investigating where our blind spots are as far as racial bias is concerned.

We need a racial bias audit—of the solicitor’s office, not simply the police department and the sheriff’s department. That needs to be done by an independent advocate and also needs some means of community input, because any racial bias audit has got to go to the community to hear what their complaints are. This is how we create community accountability, especially in an area in the South when we know that folks are marginalized, especially racially. What we’ve done is create our community action team: These are people who are connected to various networks in our community, and they’re a continual accountability measure. We want this to be part of the solicitor’s office.

Your opponent recently, in July, launched an initiative to collect demographic data and information about some charging and sentencing decisions. What is the difference between the racial audit that you were describing and that initiative?

I think that a major issue that our community has with our current solicitor is an issue of trust. We need all cases to have all the data that is available to the public to the greatest extent possible. But we’ve also got to be finding other data sources that we’re not even asking about: The huge problem when it comes to criminal justice in our area is that we’re not even asking the relevant questions. We’re not gathering the relevant data. It seems that we’re not really trying to find what the root causes of crime are, so that we can understand criminal behavior.

What is a relevant question that you think isn’t being asked, and how would the racial audit approach capture that?

It’s not enough to say, “OK, we’ve got racial bias in terms of our criminal procedure.” In every single step there’s racial bias: It’s why it’s systemic racism. We’re trying to keep people safe, reduce crime, increase people’s access to their rights. If we don’t have a real idea what their life is like, and we’re not gathering the data that reflects that, and not really interested in finding the root causes of crime, then we’re not really interested in what we’re communicating. Part of that is socioeconomic data, family situations.

An example is a teenager who is 15 years old and was caught for marijuana possession. How many parental figures do you have to watch you throughout the day? What kind of transportation resources does he have to go to after-school programs? What about how many vehicles does the entire family unit have access to? We can come up with a prearrest diversion program, but if we don’t know that the kid who’s involved in it doesn’t have any transportation resources, and his mom’s only transportation resource is a vehicle used for two jobs, then what are we doing? Before you know it, some ludicrous line prosecutor is going to suggest that we put this kid away for years and try him as an adult.

So you are saying, to audit the racial injustice of the criminal legal system, it’s essential to have information about other systems—housing, transportation, education are not separate.

Precisely. If we continue thinking about justice as criminal justice, it’s not really justice.

It’s interesting to hear you bring up transportation resources as this is an issue that has deep ties to a prosecutor’s discretion: Advocacy groups are suing South Carolina for suspending people’s driver’s licenses when they cannot afford paying off their court debt. This is an issue that disproportionately affects Black South Carolinians, who are more likely to be pulled over, and people face prosecution if they then drive with a suspended license. Some prosecutors around the country, for instance in Nashville and Memphis, have announced they will not prosecute cases for driving with a suspended license. Would you?

The presumption needs to be that we’re not going to criminally prosecute those cases. A disportionate share of Charleston’s African American community is at or below the poverty line. What are we doing when we prosecute cases for not having a driver’s license? We’re taking people who are in a deep resource-starved hole, and we’re putting them in an even bigger hole. We’re eliminating their transportation resources.

What other prosecutorial tools do you think have been wielded in a way that’s too punitive?

I think it’s easier to answer your question when we look at some of the things that more progressive prosecutors are doing: seeking lighter sentencing; making sure that we don’t use unethical charging procedures like adding charges that you’re going to drop anyway and creating leverage of time in jail to get somebody to plead guilty to something that they may not have done in the first place; trying to really eliminate or reduce cash bail at every opportunity; making sure that people are represented during bond hearings. And we need an additional community relationship aspect to it, to build trust, to get the information flowing back and forth.

And there are funding issues, making sure that public defenders are more well funded.

Let’s look at marijuana. According to a recent study, in Charleston and Berkeley counties, Black residents were four times more likely to be arrested than white residents. Would you prosecute cases involving the possession of marijuana or would you not charge these?

No, not at all.

What about cases involving possession of other drugs? On your website, you recommend a list of books for people to read, many of them about mass incarceration (with the caveat that you don’t agree with everything in them). One is “The New Jim Crow” by Michelle Alexander, who argues that the policies that have fueled the war on drugs are mechanisms of “racialized social control.” What lesson do you draw for how you would approach drug possession? Do you think the criminal legal system should be involved at all? And if you think it should, would you have a goal of avoiding incarceration and/or convictions?

I really don’t want to see convictions for those cases. But I do want to see data. The studies out there really show us that a great many of these crimes are either poverty or mental health crimes, and they should be treated as part of a larger health issue. But I think that if we’re going to take immediate steps to communicate to all law enforcement officers and all communities that we’re not even going to look at any of this kind of stuff, then we have really better make sure that we have the infrastructure to gather the data and address the health problem as well. An issue is that we don’t: We don’t have enough state funding to have a public health infrastructure.

The goal is that within the span of one four-year term, we go from where we are now to no drug possession charges. But we can’t simply stop it right away because a key element of what we’re doing is trying to gain the trust of community members.

Another proposal we hear nationwide, as to what prosecutors can do for accountability, is to maintain a public “do not call” list of police officers with a history of wrongdoing they will not rely on. Would you do so?

Absolutely. Having a do not call list is a great idea, and I know some good prosecutors around the country are doing it. And in Charleston we’re rife with a history of racial bias by law enforcement officers.

Another book on your list is “Prisoners of Politics” by Rachel Barkow, who argues that on top of the moral and human injustice, the “tough-on-crime” practices or policies have been harmful in the sense that they haven’t promoted safety. What is your perspective on that?

This is a personal thing for me. I was held up at gunpoint back when I was living in Richmond, Virginia. It really affects your perspective. But ultimately, most victims and survivors who I’ve spoken to want to make sure that this does not happen to somebody else. If we look at things from a safety standpoint, are we going to put somebody in prison for an extended period of time, especially if they’re not an imminent threat to the community? Ninety-five percent of the people in jail or prison are getting out of prison. We know that prison actually makes people more likely to do crime, especially violent crime, increasing stress and decreasing personal growth and access to all kinds of resources.

Your opponent, Solicitor Wilson, has spoken up for legislative proposals that would toughen some sentences. She has said for instance that the state’s “truth in sentencing” statutes (which require that people serve at least 85 percent of their sentence) be expanded to more cases. She has also proposed toughening penalties for unlawful carrying of a firearm. What do you make of these proposals, and how do they fit what you were just saying?

That’s not what we need. This so-called tough on crime stuff doesn’t work. It doesn’t reduce crime. It really perpetuates crime: It manufactures people who have no other perceived path. What we’re doing with these kinds of policies is we’re creating a floor, we’re creating a crime rate which we will never go below, because we are consistently using our current incarceration system to turn out people who have no resources to do anything but reoffend. We’re perpetuating the depletion of the resources that a lot of times get people in the situation where they offend to begin with. We create a gotcha system, that our law enforcement officers are incentivized to go along with. It’s oversensitizes police to waste time on bringing those people back into the system.

We could save a whole lot of money and reduce crime substantially, like we are doing in other places around the country, if we just shut off the mass incarceration mindset, and said we’re gonna focus on what reduces crime. Mass incarceration, longer sentences and putting more people in jail just doesn’t do it.

An issue you’ve talked about in your campaign is the composition of the jury pool, and how many prosecutors are likelier to strike Black jurors from the jury pool. What exact policies would you implement to avoid this? I ask because it’s been, legally speaking, rather easy for prosecutors to get around rules against racial discrimination through excuse.

There was a study in 2016 — the study that was limited, and I understand criticisms — and it said that our solicitor, in the cases that were evaluated, struck African American jurors seven times more often than white jurors. We know that when juries are all white, or nearly all white, the chance that an African American defendant is going to be convicted is substantially higher. And that should be a major concern, especially with the backdrop of inequity in Charleston area.

It has to be a multifaceted approach here. First and foremost, don’t strike a juror because of the way that they’re dressed, or the way that their hair is, or because of what a white person thinks that their mood is. Another thing is that In South Carolina, you don’t have to be compensated for your time on the jury; jurors in Charleston county and Berkeley County get paid 25 bucks a day to be on the jury. Well, if you’re hourly and working a full day shift, you’re getting 80 bucks to 100 bucks a day. So you end up paying the court system for your jury duty time. So how are we going to get by that? I’ve started working with members of county council to have more juror pay or at least have the option of people being paid a full day of living wage for their jury service so they don’t have to worry about that. It also takes community involvement. It takes having a “community action team” that is primarily African American to say we’ve got members that are elevating your voice, and it takes hiring African American attorneys.

A lot of what we’re discussing, in terms of charging levels and involvement in the criminal legal system, shapes people’s right to vote through felony disenfranchisement. How would you want that change, if at all, in South Carolina?

In South Carolina, once you’re off probation and parole, your rights are automatically restored. But a lot of folks don’t know that. We don’t have any programs to let people know that they have these rights. They think if they’ve been arrested before, they can’t vote. They’re afraid to show up at the polls because they’re afraid they’re going to be harassed because they owe some fees. So the first part is, you should have your rights restored even as you are on parole and probation.

As long as the law is not changed: There are cases nationwide where individuals who make a mistake and cast a ballot while on probation and parole are prosecuted and sent to prison. Would you ever file criminal charges against an individual who has cast a ballot while on probation and parole?

I really can’t see that ever happening. We know also from data that actual voter fraud is such an extraordinarily rare occurrence. The data shows it time and time again that it’s not much of a concern and prosecuting those cases often has a chilling effect on other people voting. So no.

A concern voiced about progressive prosecutors, writ large, is that they often end up pursuing law enforcement solutions to things best left outside of criminal justice. One book on your list, “Usual Cruelty” by Alec Karakatsanis, advances a version of that criticism, for instance. How would you, as solicitor, shrink the system’s foothold and through that your own authority?

I think that it’s not practical to think that you can absolutely completely overhaul a system if you want continued buy-in and investment and trust from your community. But the overall goal of a prosecutor should be to prosecute less crime, make his or her own position less necessary. And that’s what we should be doing. If we’re doing our job right, then we have less reason to have all these resources devoted to justice and all these biases. We can reduce the cost of the system. We can increase funding for education, for healthcare, for housing, for transportation.