‘Everything Was Just a No’: Progressives Frustrated After Colorado Legislative Session

Democrats sank headlining criminal justice reforms, like shielding preteens from prosecution or streamlining clemency, plus other progressive goals from rent control to gig worker protections.

Alex Burness | May 26, 2023

The backers of House Bill 1249 had good reason to think this year would be different.

Their goal was to end the criminal prosecution of children under age 13 in Colorado, where, The Denver Post has reported, close to 1,000 kids that young are arrested annually. Colorado children as young as 10 are liable to face criminal charges—and then, often, plunge into prolonged cycles of contact with the court system—sometimes for minor actions like snapping a classmate’s bra strap or getting into a schoolyard tussle.

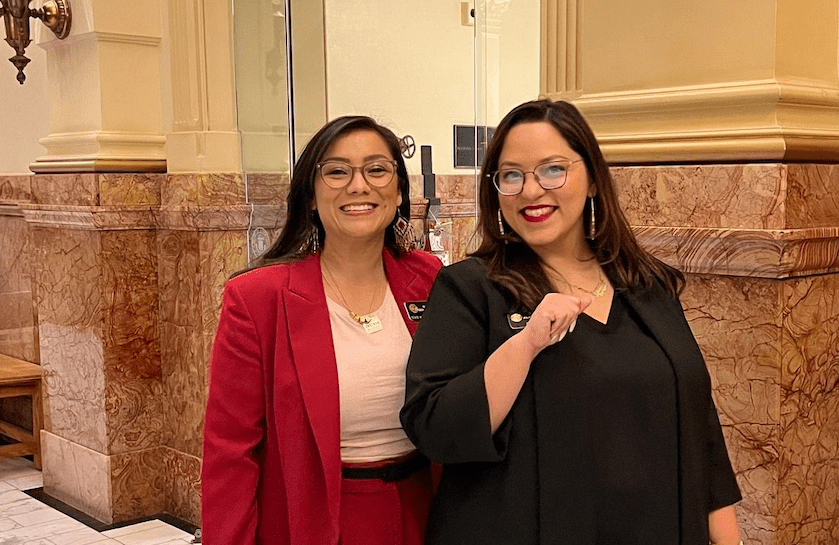

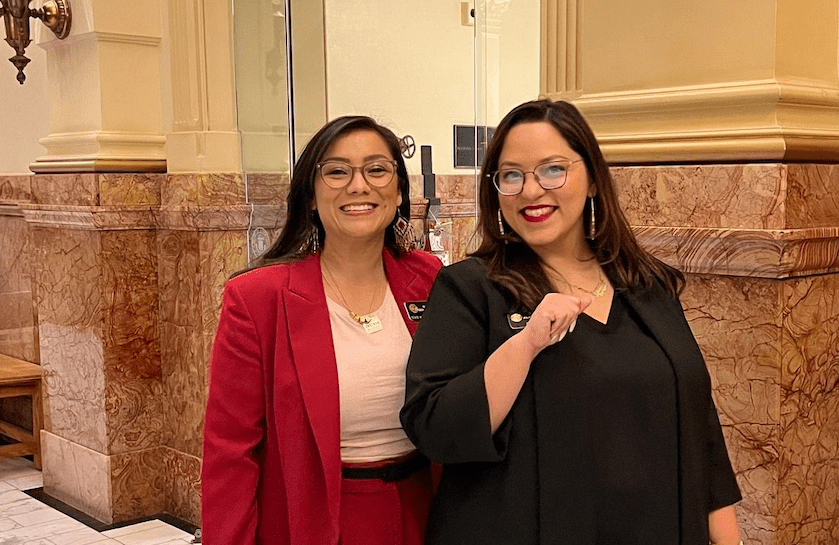

Three lawmakers—all women of color representing Denver—tried last year to shield preteens from prosecution and divert them to community programs outside the carceral system. Their proposal derailed amid law enforcement opposition and what its proponents saw as an unwillingness to hear out communities of color where children are most vulnerable to arrest. Heading into 2023, the coalition amended its approach: Two of the women who sponsored last year’s version stepped back, and in their place the group recruited three new male sponsors, two of them white Republicans.

“We kind of had this idea that we can’t have only women of color dying on these hills again,” says Representative Serena Gonzales-Gutierrez, the only lawmaker who stayed on as a prime sponsor both years. “We think that led to not being able to get it across the finish line, us having to validate our experience.”

Senator Cleave Simpson, one of the new Republican sponsors, says he was initially hesitant but was convinced to push for alternatives to criminal punishment for children that young. “To think about 10-, 11-, 12-year-old kids ending up in handcuffs,” he told Bolts, “I haven’t been touched like that by a policy conversation before.”

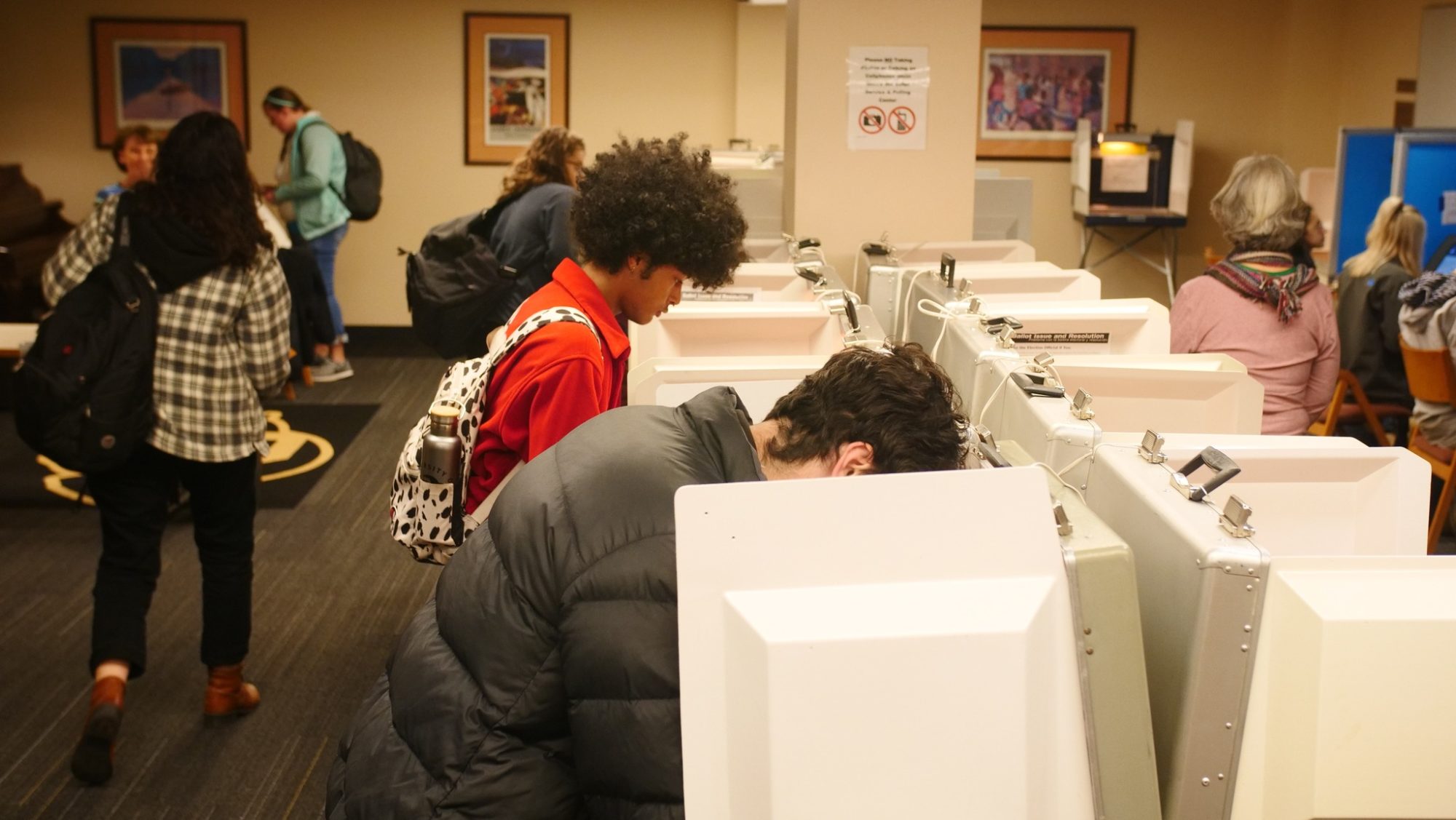

As the backers’ strategy changed, so did Colorado’s political landscape. Defying expectations of a red wave, voters in November instead strengthened Democrats’ control of Colorado’s state government, re-electing Governor Jared Polis in a blowout, expanding his party’s margins in both houses of the legislature, and further undercutting a diminished GOP’s ability to block progressive change. Heading into the 2023 session, the state’s Black and Latino legislative caucuses each identified the youth prosecution bill as formal priorities, more than 60 organizations signed on in support, and the coalition backing the bill held more than 100 meetings with people and groups invested in the topic, Gonzales-Gutierrez told Bolts.

Despite these favorable conditions, HB 1249 sputtered once more. It was gutted in the last days of the session and rewritten without most of its teeth. Lawmakers again declined to raise the minimum prosecution age, this time replacing the heart of the proposal with provisions for more funding to local social service providers and more data collection on post-arrest outcomes for children.

The neutered bill was sent to the governor’s desk, where it still sits. Even its sponsors don’t see that as much of a win.

“We’d checked all the boxes,” Gonzales-Gutierrez told Bolts. “We made it bipartisan. We had hundreds of stakeholding meetings. We met with DAs, who weren’t willing to give us substantial feedback. They said, ‘We don’t want to do this.’ From pretty early on, the governor’s office was in opposition; they wouldn’t even provide technical feedback. Everything was just a no.”

Dafna Gozani, an attorney with the National Center for Youth Law who helped advocate for the Colorado bill, echoed the disappointment. “Everybody forgets we’re talking about fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-graders,” she said. “It’s perplexing, particularly when you have a Democratic Party that runs on a platform of social justice.”

The record of the 2023 legislative session in Colorado, which ended May 8, has led to profound frustration—boiling into public view—from more progressive-leaning lawmakers and state advocates who regret missed opportunities to pass headlining liberal policies.

Democratic legislation to allow cities to establish safe drug-use sites or rent control programs failed, as did proposals to ban assault weapons and install new protections for gig economy workers. Earlier this month, in the session’s final days, a pro-tenant bill meant to thwart evictions in which landlords haven’t proved cause to evict withered alongside a bill to study the idea of moving Colorado to single-payer health care system.

Even when a bill makes it past the legislature, Polis’ pen can loom as an uncertain hurdle. The governor vetoed a bill last week that would have offered more transparency to people applying for executive clemency, helping them navigate the process even without attorneys.

Liberals did have reasons to celebrate as the legislature adopted some noteworthy policies they’d championed, including bills to strengthen protections for abortion and gender-affirming care, plus four gun-control policies. Criminal justice reformers also won passage of a law intended to help protect children from being tricked by law enforcement in police interrogations.

Still, Representative Javier Mabrey, a newly-elected progressive, faults his party for doing less with more. “I think people know what they’re getting when they’re voting for Democrats: They’re going to do things for renters, do things to help working people, to fight for communities of color,” he told Bolts. He regrets that his party chose instead to frequently preserve the status quo.

Gonzales-Gutierrez concurs: “It’s just a lot of the same.”

For reform bills this year, the Senate was the primary graveyard. Democrats there have many votes to spare, having expanded their majority since the last session by three seats to 23-12, but some of their senators resisted progressive priorities.

The youth prosecution bill passed the House but, in the frenzy of session’s end, its sponsors learned that they had lost too many Democrats to push it through the Senate; only one Senate Republican, Simpson, was willing to cross over in support. Several Capitol sources told Bolts that the governor was quietly threatening a veto while the bill was still intact. Simpson said he believes this made several lawmakers nervous they would “stick out their necks for nothing.”

A Polis spokesperson told Bolts that the governor is still reviewing the bill before signing it, but that his concerns “were shared during the legislative process and were largely addressed by the sponsors and proponents.” The spokesperson declined to answer questions about Polis’ specific concerns. Opponents of the bill argued that diverting to social service providers would not be appropriate for serious offenses—ahead of the session, sponsors amended it to carve out homicide cases—and that the juvenile system is already equipped to provide services to preteens.

In another instance, HB 1202, which would have allowed the opening of Colorado’s first safe drug-use site, passed the House before dying in a Senate committee. Following that vote, progressive Senator Julie Gonzales said it was “incredibly disappointing” to see a public health response to overdoses falter despite “the broadest majorities that this state has seen in a generation.”

Most Republicans opposed those reforms, but the GOP was largely relegated to spectatorship this session, watching intra-Democratic strife settle the fate of key legislation. Republicans are just one Senate seat away from superminority status in both chambers. “It’s always darkest before the dawn, but the problem is you don’t know when the dawn is going to come,” Republican Senate Minority Leader Paul Lundeen told Bolts.

And many progressives believe that Democratic leaders followed their November romp by building infrastructure within the legislature to thwart progressive change. They cried foul on committee design weeks before lawmaking ever began.

In one instance, Dylan Roberts, a former prosecutor with a lengthy record of siding with law enforcement and Republicans to oppose bold criminal justice reforms, was named as one of the three Democrats on the state Senate’s Judiciary committee. With no vote to spare on any legislation opposed by the panel’s two Republicans, this arrangement seemed to virtually doom key legislation that Roberts did not support and alarmed reformers from the session’s outset, as Bolts reported in January.

On that committee, Roberts helped weaken, through amendments, bills to limit local cooperation with federal immigration enforcement and to examine the cost of policing and incarcerating drug activity in Colorado, among other legislation. Roberts played a decisive role in sinking the rent control bill when he sided with Republicans in committee.

And Judiciary was not the only chokehold, Mabrey says. He complains that the design of numerous Senate committees, including Appropriations and Finance, forced Democratic lawmakers to repeatedly cut into their own bills based on the opposition of centrists.

Steve Fenberg, the Senate’s Democratic president and a close ally to Polis, told Bolts there was no concerted effort by party leaders to thwart progressive policy.

“Nothing was done to set up roadblocks,” he said. “Why would I do that? I’m a Democrat. I consider myself a progressive. I’m the leader of my caucus. Why would I do something that inherently tries to block my members’ priorities?”

Committee design came organically, he said, adding that members requested assignments based on their own backgrounds and interests, and that leadership did its best to accommodate them.

Fenberg said it’s irresponsible to read very far into the size of Democrats’ majorities. “I think people assume there’s 23 [Democrats in the Senate] and therefore they can pass anything they want,” he said. “We forget this sometimes, but people make decisions based on policy, and some of these bills didn’t have the support from what I would call progressive members of our caucus.

“It shouldn’t just be, ‘Oh, we have this many Democrats, therefore any Democrat bill gets passed.’ I actually think that would be bad.”

Speaker Julie McCluskie, a moderate Democrat who leads the state House, echoes Fenberg’s assessment and says Democrats must continue at least trying to work with Republicans.

“We were each elected from our districts, and while the Democrats have a supermajority [in the House], I believe to my core that if we are going to craft lasting policy for this state we have an obligation and responsibility to hear from our own caucus, our Republican colleagues and from our districts,” McCluskie told Bolts. “I know that there were many Republicans that worked in a bipartisan way.”

Steph Vigil, a Democrat who flipped a Colorado Springs House seat in November to become the first queer lawmaker from the red bastion of El Paso County, disagrees with legislative leaders and hopes they change their approach. “I respect the love for the institution to want it to be that way, but I think we’re dealing with some truly genocidal people,” said Vigil, pointing to racist and transphobic rhetoric and legislation from the GOP.

“People asked us for something, they asked for us to be bold,” Vigil added. “You’re not here to make friends with people who wish you harm.”

But Fenberg cautions against his party going too far, too quickly. “Don’t underestimate what infighting and controversies within our own party can do,” he said. “If the Republicans want to get control, they have to get their shit together. … If we don’t get our shit together and we go down a path of polarization in our own party, that speeds up the process for Republicans.”

As lawmakers tried to keep the youth prosecution bill intact in the session’s final weeks, they were also pushing for HB 1042, a related bill meant to prevent police from lying to children during interrogations in order to secure information or guilty pleas. Deceitful interrogations are a leading cause of wrongful convictions across the country, including in Colorado, the National Registry of Exonerations has found.

When a previous version of HB 1042 derailed last year, Roberts was a rare Democrat to oppose it. So when he was promoted ahead of the session to being the swing vote on the Senate’s Judiciary Committee, reformers immediately sweated their proposal, and Roberts confirmed their fears in January when he told Bolts that he would oppose it again barring substantial amendments. From January to April, its sponsors agreed to a slew of changes that loosened the bill; they reluctantly signed off an amendment allowing for information or confessions obtained through deceitful interrogations to still be used against children in certain court settings, like hearings to determine bond or whether a child should be removed from their home.

The bill’s backers also tried to make their effort seem less adversarial toward law enforcement, no longer using words like “lying” or “deception” in their marketing of the bill.

The changes were ultimately sufficient for the District Attorneys’ Council, a historically influential body that lobbies on behalf of state prosecutors, to drop its opposition, and for Roberts to support the bill. HB 1042 passed the legislature in April, and Polis—who, lawmakers say, was earlier quietly threatening a veto—signed it into law last week.

Progressive lawmakers have cheered passage of this bill, as the amended version remains closer to their original intent, in contrast to the youth prosecution bill. Still, they say even this victory came with more concessions than it should have, given the nature of the issue and Democrats’ enormous structural advantage, weakening the bill’s potential to shield kids from duplicitous tactics.

Gozani, the youth justice attorney, was incarcerated in Colorado as a child. She says the experience was “traumatizing and incredibly damaging” and regrets that in the two decades since then, Colorado’s approach to youth has remained largely similar, and punitive.

She hoped that HB 1249, the preteen prosecution bill, would chip into that system. After its clipping, Gozani isn’t sure if the coalition behind it will run their proposal again next year. With no legislative election this fall and the same Capitol leadership structure expected in 2024, it’s hard for reformers in this and other policy spaces to envision how exactly they achieve victory.

Gozani has found that, regardless of partisanship, it’s difficult to convince people who never have experienced the juvenile system, or whose children never have, of the need to make that system less punishing.

“A lot of folks have the luxury of never having to interact with the justice system,” she said. “For them, it’s very comfortable to continue a status quo that is extremely damaging.”