Connecticut Governor Scrambles Pardons Board and Halts Clemency

The chair of the state’s pardons board had revived a narrow pathway to release people who are serving decadeslong sentences. Then Ned Lamont removed him.

Kelan Lyons | April 28, 2023

Republican lawmakers in Connecticut hosted a press conference last month in front of white silhouettes cut in the shape of mugshots. Each image represented an imprisoned person who had received clemency by the state’s Board of Pardons and Paroles. Black text overlay where their faces should have been, stating what each individual had been convicted of, the length of their sentence, and how many years the board had shaved off.

The GOP had staged the event to protest a rise in clemency in the state. After years of a near-total freeze in commutations—a rare path out of prison for hundreds of people who are serving decadeslong or life sentences in the state—the board granted several dozens in 2022. That fell short of reformers’ demands but the GOP still took issue. “I am calling on Governor Lamont to stop this right now,” said John Kissel, the highest-ranking Republican senator on the Judiciary Committee, who was accompanied at the event by families of violent crime victims.

Governor Ned Lamont, a Democrat, followed Kissel’s call on April 10, removing Carleton Giles, a former police officer, as chair of the board. Giles, who is Black, had authority as chair to decide which board members would hear commutations, and Republicans painted him as the architect of the rise in releases.

Lamont appointed Jennifer Medina Zaccagnini to replace him as chair. Within days Zaccagnini put a hold on all commutation hearings until further notice.

Lamont’s move dismayed state advocates who have pushed Connecticut to reduce its prison population and address persistent racial disparities in incarceration.

“For a parole chairman—who is a police officer, who was doing his job according to the law—to be removed for such a small number of releases, it sends a chilling effect that could set us backward in criminal justice reform for years, if not decades,” said Alex Taubes, an attorney who has represented dozens of people who received commutations from the board.

Connecticut drastically lengthened prison terms starting in the late 1980s. This led many people who committed violent crimes as teenagers or young adults to receive prison terms that makes it likely they’ll die behind bars unless they receive clemency.

“The longest sentences have not generally gone in Connecticut to the worst criminals. They go to the people with the worst lawyers,” Taubes told Bolts. “That’s why the group of people who are eligible for commutations is disproportionately Black and brown people, who don’t have the kinds of networks and connections that allow them to get the lesser sentences in the first place.”

Roughly 700 people are serving life sentences in the state and can expect to die in prison without clemency, according to a study by the Sentencing Project. The majority of them are Black. (Only 13 percent of Connecticut’s overall population is Black.)

Those disparities meant clemency has overwhelmingly benefited people of color. The board identified that nearly two-thirds of the people who received commutations in 2022 are Black, and a quarter as Hispanic. “Stopping the commutations is a racist policy,” Taubes said.

Taubes and like-minded advocates have pressured the board to give people growing old behind bars a second chance but they’ve been frustrated by what they see as a dysfunctional system. Connecticut is one of six states where the power to commute a prison sentence is vested entirely in an independent body with no direct role for the governor. The board has “unfettered discretion” in how it uses its commutation powers, an unusually broad mandate that has at times proved paralyzing. During the early pandemic, as other states acted to relieve prisons, the board was accepting no applications and issuing no commutations.

Even over the past year, under Giles, the board kept the pathway to clemency very narrow. In 2021 and 2022, it restricted the criteria to be eligible to even ask for a commutation, for instance forcing people to wait two additional years to apply. It also decided that people who are serving sentences of life without parole are ineligible to receive a commutation. Miriam Gohara, a professor at Yale Law School who has represented two people applying for commutations, insists that state statute says they should be. “That was something that they should not have done, but I think they did it as an opportunity to try to assuage their critics,” Gohara said.

The board is denying most applications. Its statistics show that, in 2022, more than three-fourth of applicants were rejected.

But the board also took steps to flex its clemency powers. In 2021, it began taking applications after a two-year hiatus. Its first commutation in two years shortened a sick man’s 75-year sentence so he would be eligible for compassionate parole, a program meant for people with long sentences and serious medical conditions.

They also took a new look at people who were sentenced to long terms as kids or young adults, a population that makes up the bulk of those granted commutations in 2022. In recent sessions, some legislators proposed expanding release opportunities for people who committed crimes before age 25, pointing to scientific research that shows the brain keeps developing until the mid-20s; while their bill proved unsuccessful, the board soon appeared to heed their arguments.

“You’re talking about younger individuals who were sentenced in the ‘90s for sentences that we would not give out as a state anymore,” said Representative Steven Stafstrom, a Democrat who co-chairs the Judiciary Committee. “We are living in a very different era, I think in the nation but certainly in Connecticut, in terms of how long folks should be sentenced for certain crimes, particularly crimes that were committed at a very young age.”

“What these commutations did is modernize or correct the sentence, based on what today’s sentencing guidelines would be,” he said.

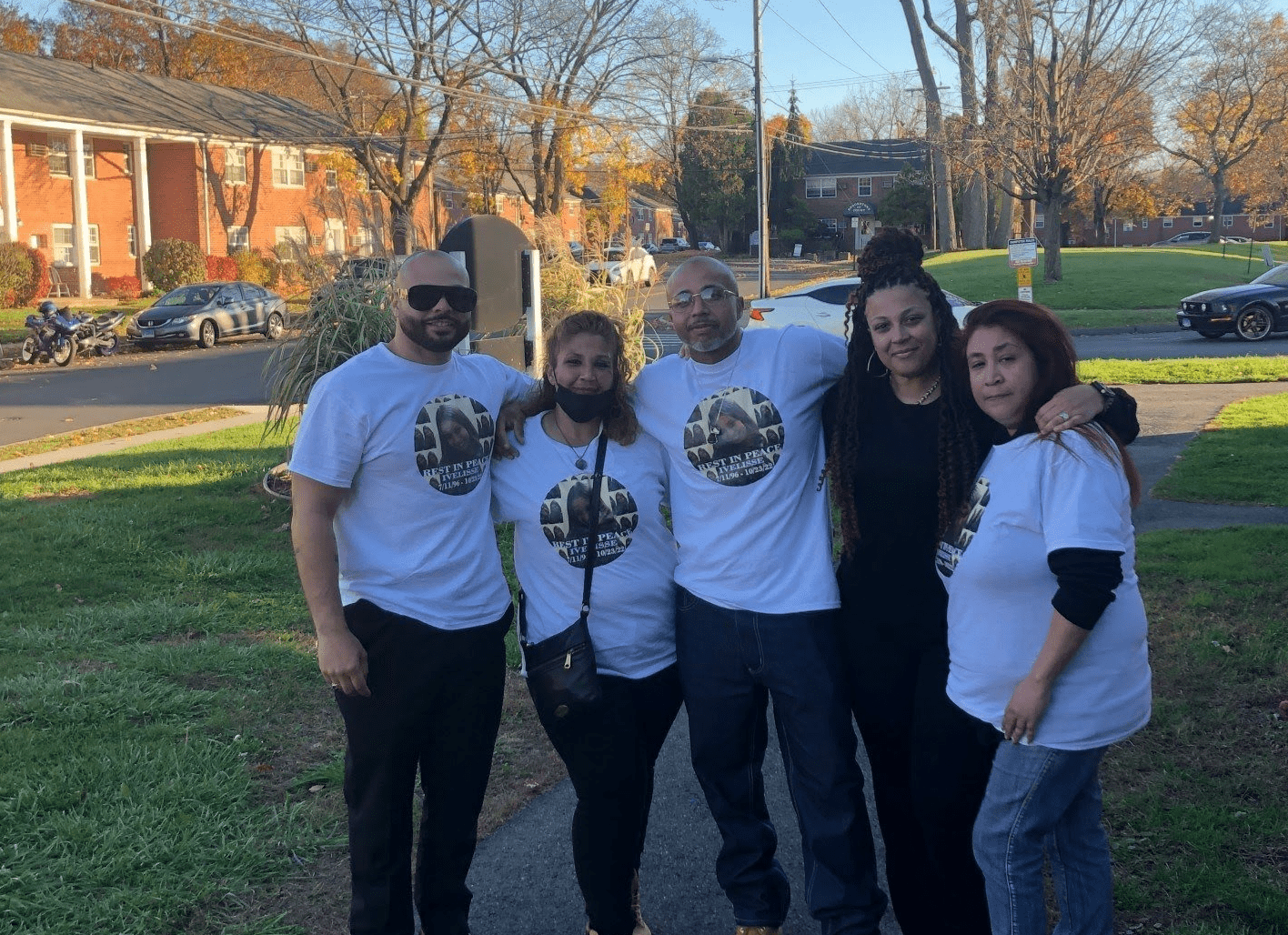

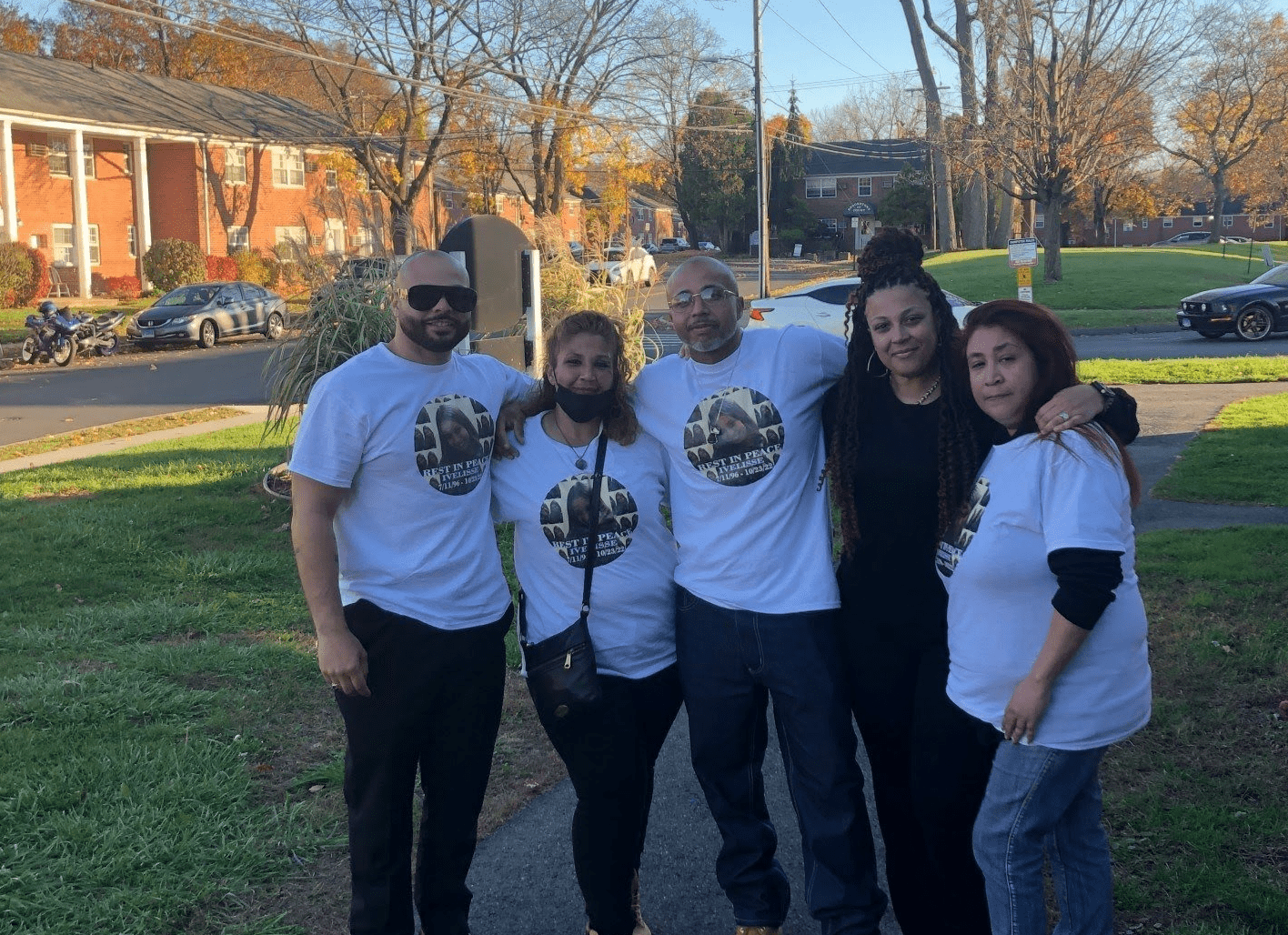

Julio Rodriguez is among the people who benefited from this second look. After more than 22 years in prison after being convicted as an accessory to murder, he was sent to a halfway house in July after the board commuted over two decades off his 50-year sentence.

“When we was younger, some of us don’t even know what the heck we was doing. We was just doing it under peer pressure, under the gangs, under drugs’ influence,” he said. “It’s kind of like hard for somebody that came really young like that and grew up in jail and never had a chance to become somebody.” He added, “We became men in there, grandfathers. We was kids.”

Rodriguez was 19 when he went to prison. Now, he has a job detailing cars, and he says he wishes the public knew about all the people he left behind in prison who, like him, bettered themselves even though they had years left on their sentences.

“There’s people in there that deserve a chance,” he says.

The decisions made by Lamont and his new appointee, Zaccagnini, have put their hopes on hold.

“Maybe it’s time to take a pause and let the legislature weigh in on what they think the rules of the road ought to be and make sure the advocates on both sides are at the table so we have a full discussion,” Lamont told The CT Mirror. After the board held a meeting with state officials and lawmakers last week, Lamont’s spokesperson said there would be no new commutations until “an expeditious review” of the board’s policies.

The governor’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

Lamont has generally taken a different tack on criminal justice than his predecessor, Democrat Dan Malloy. Malloy promoted initiatives that reduced punishment for drug possession offenses and expediting pardon and parole processes, advocating for what he called a “second chance society.” Malloy also pressured the board to grant more parole applications.

Lamont largely ignored calls by criminal justice reformers to use his soft powers—that includes the authority to fire and appoint the board’s members—to push for more releases during the pandemic. When the GOP made the inverse argument this year, he acted to force a pause.

Connecticut Republicans have mounted tough-on-crime attacks for years, including targeting Lamont and other Democrats in the run-up to the 2022 midterms. In 2021, they convened multiple press conferences about car thefts. But Republicans did poorly last fall. Lamont won re-election by double digits and Democrats expanded their legislative majorities.

“Voters in Connecticut sent a clear message in the fall that they were not buying whatever narrative the Republicans were trying to sell on crime,” said Gohara.

Despite these defeats, Republicans kept up their attacks on the board for being too willing to approve applications. At the press conference last month, they warned that “serious criminals” and “violent offenders” were being let out of prison decades before the end of their sentences.

The board granted zero commutations in 2020, then only one in 2021. In 2022, it granted 71, a surge but still a small share of Connecticut’s incarcerated population. As of April 1, 2023, there were 10,010 people in the state’s unified system of prisons and jails.

“This is why this whole thing is kind of absurd: the board has been relatively conservative in its approach to its power,” says Democratic Senator Gary Winfield, co-chair of the Judiciary Committee. “People saw a spike, recognized an opportunity to put victims in front of everybody and say, ‘We’re doing the wrong thing,’” he added.

Michael Lawlor, an associate professor of criminal justice at the University of New Haven and under secretary of criminal justice policy and planning under Malloy, champions commutations as an important tool for rehabilitation.

“Should we have some type of avenue to consider some of these folks for a shot at release before they die?” he asks. “Without this option, there’s no hope at all that they will ever get out, and there’s no incentive to behave yourself, and there’s also no incentive to do anything constructive: take courses, express remorse, demonstrate that you’re a different person.”

Despite losing the chairmanship, Giles will remain on the Board of Pardons and Paroles as a regular member. Both legislative chambers voted to reappoint him to that position in April, even though some Democrats joined Republicans in opposing him. Two other board members who decided on commutations with Giles also survived legislative votes.

But Giles will no longer be in charge of the commutation process and he lost the prerogative of shaping the rules and deciding who gets to hear commutation applications.

Taubes says Giles’s demotion is a blow to reformers’ hope of using clemency to lessen incarceration. “If parole boards become subject to the political whims of the moment, let alone the least common denominator of some Republican misinformation campaign, then we will never be able to realize the potential value of parole boards in criminal justice reform,” he said.

Similar dynamics have percolated in other states like New York or Virginia, where reformers hope that state officials will staff the boards responsible for commutations or parole with people who are more open to second chances, while Republicans have sought to block changes. In Pennsylvania, which has near-record numbers of people serving life sentences, then-Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman worked to make the state’s Board of Pardons much more amenable to clemency and faced heavy GOP attacks over it in 2022, only to win his U.S. Senate race.

Fetterman appointed formerly incarcerated Pennsylvanians and decarceral activists to work for the board. “We’ve all been in need of mercy and forgiveness at some point,” Celeste Trusty told Bolts last year after she became secretary of the board. (Trusty left the board this year after Fetterman went to Washington.) “But that’s not applied at all to how we sentence people.”

Gohara is dismayed that Connecticut, a former leader in criminal justice reform, now seems to be turning its back to that perspective.

“If it’s happening in Connecticut,” she said, “then you can only imagine, ‘Where else would be vulnerable to this?’”