His Shock Win Flipped a Pennsylvania County. Now He Vows to Raise Hell over Its Lethal Jail.

Pastor and activist Justin Douglas will soon be plunged into an insider role, helping run the state’s capital county. Can he leverage his new power to change Harrisburg's deadly facility?

| December 21, 2023

Bolts this week is covering the crisis in local jails, and the county boards that oversee them, with a three-part series. Read our reporting from Houston, from Los Angeles, and from Harrisburg.

There are many paths to elected office, Justin Douglas quips, “but fired pastor is not one.”

A year ago, he says, he could not have named the three men who serve on the county commission of Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, his home since 2015. This powerful body, with control of a $222 million budget and a county government workforce of 1,700, meets Wednesdays in downtown Harrisburg, in a building that Douglas had never entered.

Still, he got a call in February from Run for Something, an organization that recruits progressive candidates for local elections, to see if he’d be interested in running for a seat on the county commission. The last time the office was on the ballot, in 2019, Douglas did not vote. He’d just been fired from his job as pastor at a local church for appearing in a promotional video welcoming LGBTQ+ people to join the congregation. He, his wife, and their three kids were forced out of the home, which was owned by the church. All this time later, Douglas, 39, is still working three jobs to make up for what happened: he’s a pastor at a new church and a fitness instructor, and last year he drove more than 2,000 miles for Uber.

His stand at the church fit with what he describes as his longtime activist streak. A mainstay in various corners of Dauphin County where matters of social equity and justice are concerned, Douglas grew active in recent years in protest of conditions in the local jail, an aging and oppressive facility where people die at an alarming rate. The county commission has vast power over that jail, a significant factor, Douglas says, in his decision to take Run for Something up on its proposal. He still felt like an imposter when he decided in March to enter the race.

By any standard measure, his campaign seemed doomed from the start: He had no paid staff or office. His team of volunteers, a few friends of his with zero combined campaign experience, met in the corner of a Starbucks in Hershey. He ran without institutional backing or money; while his opponents combined to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars, Douglas reports spending only about $12,000.

And he centered his campaign around denouncing the fact that so many people have died in Dauphin County’s jail—an unusual focus, to say the least, for a political candidate.

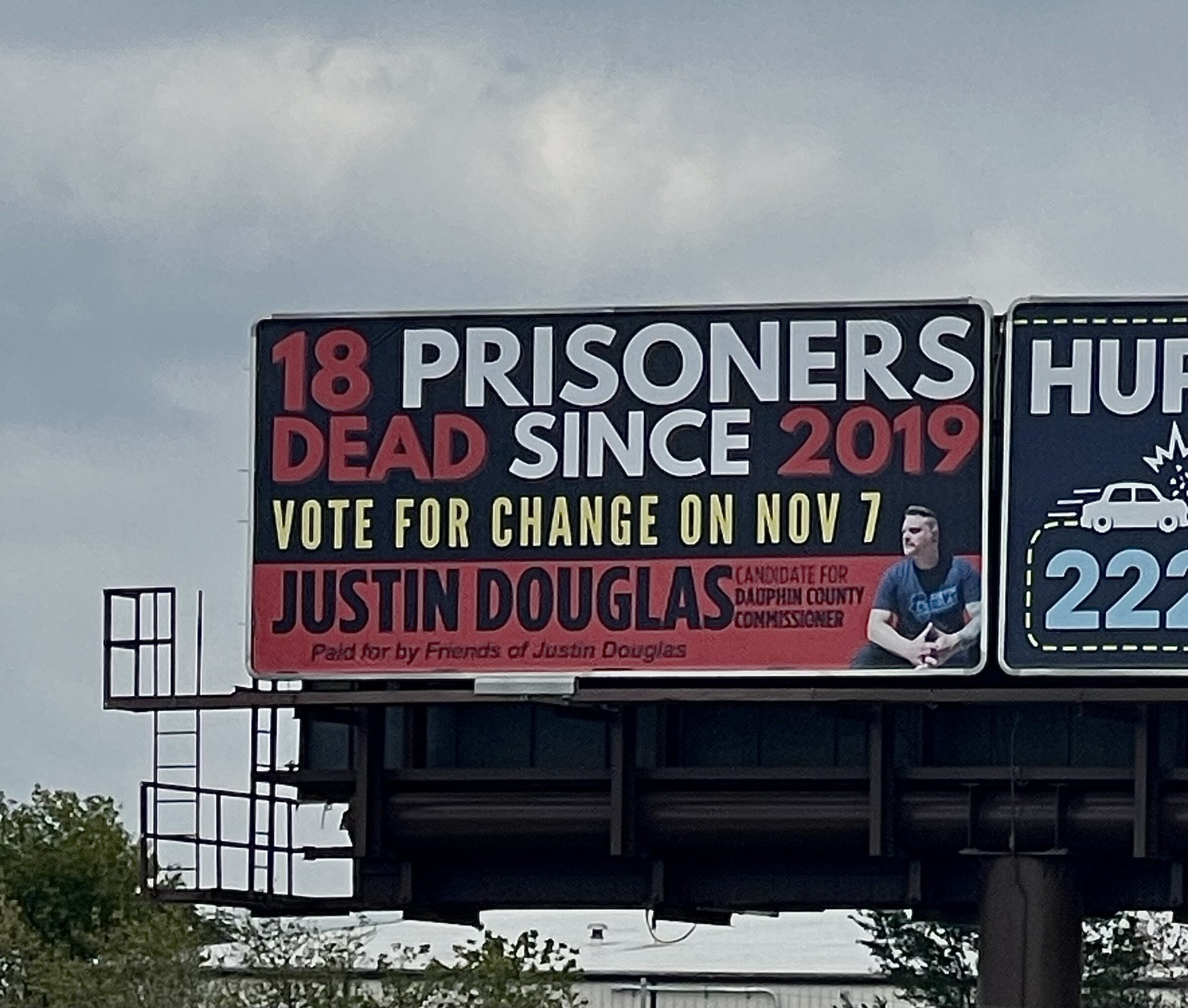

He spent roughly a fifth of the little campaign money he raised on a single, highway-side billboard highlighting the lethal lock-up, which sits between Harrisburg and the Douglas family home near the southeast edge of the county. Dauphin County has admitted at least two jail deaths in each of the last four years, a pace that stands out even by terrible national standards.

“Eighteen prisoners dead since 2019,” Douglas’ billboard read. “Vote for change on Nov. 7.”

In most states, jails are run solely by sheriffs. In Dauphin County, as in most of Pennsylvania, jails are managed directly by local bodies that each feature all three county commissioners, plus some other officials. That gives Dauphin County’s commission a potent vantage point from which to force change, but local advocates have long been angry at what they see as commissioners’ indifference in the face of this death crisis.

Douglas hammered that message relentlessly—on social media, at candidate forums his opponents didn’t bother to attend, and on the few occasions journalists reached out to interview him. The day before the election, Douglas posted on TikTok urging people to vote, a standard campaign move with an atypically specific appeal: “What got me into this race is prison reform,” he said. “Restorative justice is the solution, and we need that throughout Dauphin County.”

The following day, on Nov. 7, Douglas defied all expectations to win a seat on the commission, ousting Republican Commissioner Chad Saylor by just 184 votes. A video captures Douglas’ reaction when he learned his win: “Are you kidding me right now? Oh my gosh. Is this for real?” he says, pacing the parking lot outside of the restaurant where he’d gathered with his team.

His victory flipped Dauphin County’s three-person county commission to Democrats. This is the first time the party has won a majority here since at least the Civil War, and an exclamation point on a strong election night for Pennsylvania Democrats generally. Dauphin County now leans blue in federal politics, with Joe Biden carrying it by 9 percentage points in 2020, but Democrats have struggled down-ballot.

The upset has brought Douglas, who’ll be inaugurated on Jan. 2, a lot more attention. He says his calendar is suddenly jammed with people who’d never looked his way but now want to meet, and that he is invited into rooms he could not previously access. He’s been plunged into a new role, one that he hadn’t imagined he’d actually win, and must now figure out how to shake up the local political establishment from the inside.

When I first talked to Douglas last month, he was still processing his unlikely victory, and planning with his allies how he could turn their newfound clout into better conditions—and a greater voice—for the people detained in Dauphin County.

We met in downtown Harrisburg, early on a frigid Wednesday just before the weekly commissioner’s meeting, which he chose to attend—as a spectator, for now. He’s instantly recognizable as almost anything but a successful politician: he’s got gauge earrings, 42 tattoos, and dresses in jeans, band tees, and Nike sneakers. The morning we met, he’d put on a collared shirt and a blazer because, he said, he’s trying to look the part these days.

When we arrive at the county building, a local NAACP chapter leader joins us in the elevator and gives Douglas a hey–aren’t-you-that-guy look, then asks to grab coffee some time. Douglas takes a seat in the back row of the commissioners’ meeting room, and tells me he feels a bit out of place.

Later that morning, as he readies for an interview with Harrisburg’s CBS station, Douglas confesses that he’s got a lot to learn; that he’s not convinced the Democratic majority will work well together; that he feels icky about attending the inauguration on Jan. 2 at a fancy hotel downtown; that he’s having trouble trusting all the folks who now want to be his friend; and that he isn’t sure how, exactly, he’ll navigate the political terrain to bring about change inside the county prison that was the focus of his campaign.

The TV crew leaves and he asks me how he performed, then ponders how to best articulate his ideas going forward. “I’m figuring it out. I’m figuring out how I’m going to move differently now,” he says. “Not in morals or in authenticity, but if this is a simulation and we’re in a video game, I leveled up and skipped a few levels. I’m the dude off the street.”

Douglas is not alone in navigating these questions. He is brainstorming next moves with Lamont Jones, a like-minded reformer and political newcomer who won a seat on the Harrisburg city council in November. And he is in conversation with other central Pennsylvania advocates who are eager to build on this moment.

Onah Ossai, an organizer with Pennsylvania Stands Up, is watching attentively. She thinks Douglas’s ascent was catalyzed by the protests for social and racial justice in 2020 that, in her words, “primed people” in Dauphin County to view the jail as an everyday scandal.

“There was activism that made a candidacy like this viable,” Ossai, who met Douglas at a Juneteenth rally this year outside the jail, told me. “No one else was running on the prison or talking about it before. Justin put up a billboard, he came to prison events, he came to prison board meetings. I think people really understood that he was someone who was at least paying attention, that he was a real outsider.”

Despite its name, the Dauphin County Prison operates more like a common jail. Most of the roughly 1,000 people detained there on any given month have not been convicted and are held pretrial. Many are there because they can’t make bail, or due to violations of probation or parole. The average length of stay at the jail is 120 days, the county reports.

While the county hasn’t recently published demographic information about the people it incarcerates, many who’ve been inside of it told me the detained population skews disproportionately Black, which is in keeping with the county’s historical trends.

Many Pennsylvania jails are deadly for the people who churn through, but Dauphin County’s jail death rate still exceeds statewide and national averages, PennLive determined in a recent investigation. More broadly, the county’s own numbers show over 2,000 incidents since 2019 in which staff used physical force or deployed chemical agents on people held at the jail.

“You don’t have to live in Dauphin County long to know this is a problem,” Douglas tells me. “It’s hard to miss.”

In addition, local journalists have found that the county has often misreported its jail deaths—in some cases, covering up its own responsibility.

In one such instance, Dauphin County reported the death of Herbert Tilghman as a “medical event,” which, PennLive found, obscured the fact that prison staff failed to take Tilghman’s stomach pains seriously, providing minimal treatment and even accusing him of faking illness shortly before he died. In a separate case, the county initially said Ishmail Thompson died in a “medical episode,” failing to note that officers had placed Thompson in a restraint chair, and a hood over his head, then pepper-sprayed him soon before he fell unconscious and, ultimately, comatose.

A dozen people I interviewed for this story with knowledge of conditions inside the jail spoke of nearly round-the-clock lockdowns, and neglect for people’s mental and physical health needs.

“It’s disgusting,” Harrisburg’s Doniesha Bell told me this month, shortly after she was released. Though she hasn’t been convicted of any crime, she spent six months in jail because she could not make bail. She said she was staying at a local shelter, having no stable place to live.

“You have to sit in a cell and eat where you have to use the bathroom. You’re locked down 23 hours a day, and that’s if the guard feels like letting you out,” Bell said. “I was locked up with people who’d seen people die in there, and I get it: you’ve got to bang on the door because there’s no way to get ahold of the [correctional officers]. … The one day my blood pressure was up, they just told me to deal with it, to wait. And they never called the nurse.”

John Hayden, a local watchdog with a Quaker-led citizen group called the Harrisburg Advocacy Team, said the prison’s running crisis is the result of policy choices—namely, contracts with profit-driven companies Aramark and Primecare Medical to provide food and healthcare.

“The way they make more money is by providing lower-cost food and low-wage employees,” Hayden says. “They’ll go several weeks in a row with bologna sandwiches for lunch every day. Sometimes they’ve had bologna sandwiches for all three meals.”

These stories have spurred deep local activism. Meetings of the jail board are well attended, and some advocates have successfully pushed their way into unofficial oversight roles; the nonprofit Pennsylvania Prison Society takes regular tours of the prison and reports back to the community on what it’s seeing. Destiny Brown, a member of that group, tells me she and others in her advocacy corner were pleasantly shocked that Douglas won, and that they “hope and pray this brings change.” Her Prison Society colleague, John Hargreaves, adds that Douglas winning is “injecting a note of optimism. People feel somewhat hopeful now, whereas they didn’t before.”

Douglas told me, “I’ve moved in activist communities in this area pretty much since I got here, and there are a lot of people who’ve come before me, who are much louder than me, who have educated me on this issue.”

While I was in town to see him, Douglas toured the prison for the first time. He reports back to me following the visit: Certain cell blocks don’t ever go outside, he learned. Rather, he says, they have gym time, which the jail counts as “outdoor” time because air flows in through barred windows. Douglas says he observed in the gym that some of the basketball hoops have no rims, and learned that the jail’s juvenile unit has no working showers. He says he saw leaking water from corroded pipes throughout the kitchen, and a man naked in a cell, defecating on the floor.

He says he met another man on suicide watch, under supervision of an officer who told Douglas she is overworked and was filling in for a colleague on that day’s assignment. Douglas tells me, “That’s not a place I’d want to be in if I were in mental health crisis. That would not aid in my betterment.”

He was escorted during his tour by the county’s director of criminal justice, John Bey, a longtime Pennsylvania police chief who was hired by the county earlier this year to oversee its correctional system. Commissioners touted him as an agent of change, and Bey himself said at the time of his hiring, “My position embodies transparency.”

And so, when we spoke by phone this week, I was curious to hear how Bey feels the county can better communicate what happens inside the jail. He immediately rejected my premise and suggested that the county has been forthcoming about jail deaths, despite thorough PennLive reporting to the contrary. He acknowledged the jail’s poor reputation, but insisted conditions are improving and that “at no time in the history of this place” has accountability been higher.

“I can assure you that as a facility, as an institution, we take the care of our inmates here very seriously and we work closely with PrimeCare to ensure that inmates and those under our care receive at the very least adequate medical care to ensure they’re thriving as much as they can be, given whatever maladies they enter the prison with,” he said.

He added, “They’re not housed in their cells locked down 23, 24 hours a day.” I mentioned Bell’s claim that she had been locked in for that long. “I’m not going to say that that lady is lying,” Bey replied. “We do feed inmates in their cells. They’re very small cells.”

Douglas says he met more than 20 people detained at the jail during his tour, and some knew he’d been elected. He recounts one prisoner saying, “You’re coming in here to fix this place.” He responded, “I’m going to do what I can.”

Douglas will soon have some real power over the jail. When he is inaugurated, he will automatically join the county’s prison board, the facility’s governing body, on which all three commissioners have a seat alongside four other local officials. The board proposes contracts and settles policy questions in the jail, and it regularly holds meetings to take public input.

The three-member commission, as a separate, standalone body, has final say on budget questions and on contracts for health care, food, and other services. Douglas has been critical of the county’s relationship with those vendors, suggesting that local leaders are influenced by campaign donations from potential vendors.

None of the current commissioners—Democrat George Hartwick and Republican Mike Pries, who will stay in office next year, plus Saylor—responded to my interview requests.

Douglas vows that he’ll use his new standing to demand major improvements in detention conditions, from fixing the broken pipes to restricting solitary confinement.

He’s also aware that the best way to keep someone from dying at the jail is to make sure they never get there at all. He insists that focusing on improving economic conditions throughout Dauphin County would have that effect. He thinks the county should detain fewer people pretrial, a reform that other parts of Pennsylvania have adopted, and hopes to partner with the Dauphin County Bail Fund, a local anti-carceral organization, to highlight punitive bail practices.

But Douglas knows change will be difficult. Many of his ideas have gotten little visibility from the local political establishment until now. On the prison board, he’d need to form a broad coalition to force changes; for decisions made by the commission, he’d have to win over at least one of his colleagues.

Douglas is the first to concede that he isn’t anywhere close to functioning majorities in favor of bold jail reforms. While Douglas and Hartwick will form the board’s new Democratic majority, and could shift policy on some issues, like access to voting, Douglas is skeptical this will easily extend into criminal justice policy; the two men have little relationship so far.

“I don’t trust that everything’s better,” Ossai says. “We’ll see if they’re able to work together, and to what end, and we’ll see who holds the power. Justin’s new, he’s outside.”

But Douglas thinks his activist background is an asset and says that he is prepared to use his bully pulpit to disrupt normal proceedings in the county, forcing other officials to reckon with the deaths and the suffering happening under their watch.

He says he’ll frequently and loudly talk about what goes on in the jail. He wants public meetings on that and other topics to be understandable to the public—that is, no more sailing through agenda items without discussion. He wants meetings of the prison board to be events and hopes to invite more voices of activists, including currently and formerly incarcerated people, into those spaces. He says he’ll take journalists on jail tours and that he plans to pop in often for his own tours, sometimes without warning.

He tells me, “The prisoners whose hands I shook—I’m going to get to know their names. They’re going to see me regularly.”

Inside a coworking space in Harrisburg, which serves as Douglas’s office for the time being, he ponders these power dynamics in a meeting with Jones, the incoming Harrisburg city councilor.

Jones, too, overcame tremendously long odds to reach these heights. He’s formerly incarcerated, including two stints inside the Dauphin County jail. He’s Black, was raised in poverty in Harrisburg, and by 15 was selling cocaine. Now 48, he voted for the first time at age 39; like so many in the country, he says, he spent years wrongly assuming his felony record meant he could not vote. He’s got a close perspective on the dangers of the local jail: his cousin, Ty’Rique Riley, died after being detained there in 2019—one of 18 names behind the statistic on Douglas’s billboard.

When Jones decided to run for Harrisburg’s council this year, local Democratic power players conspired to keep him off the ballot, arguing his criminal past should disqualify him. Jones prevailed in court and again on Election Day.

In this heavily Democratic city within this light-blue county, Jones says, he has a hard time talking about his path to the ballot without crying.

“We’re in the era of criminal justice reform, right? Here, I’m someone who has exemplified that enough to be elected into a position to give hope to people who didn’t think they could do anything with a felony, who didn’t think they could get out of the situation. But none of those people who talk about criminal justice reform was willing to stand beside me,” he says.

I listened as Jones and Douglas considered how they can work together to reduce poverty, criminality, and incarceration. They know they’ll need to build consensus in circles that have upheld a status quo that is deeply punishing for communities like the one Jones was raised in.

“We’re going to have to make some relationships with some people that we don’t even care for,” Jones tells Douglas. “We may have to take some losses.”

The two men feel politically lonely and they’re already bracing for blowback, but they’re also focused on building power on the outside. “It can’t stop with just him and I,” Jones tells me. “We’re going to need more people.”

Upon my return from Harrisburg, Douglas contacts me with news of two local developments:

First, another man has died inside the prison. His name was Christopher K. Phy, he was 38 years old, and he hanged himself. PennLive reports this is the county’s 19th jail death since 2019.

Second, the county has agreed to a $4.25 million settlement with the family of Ishmail Thompson, the man who died after jail staff restrained and pepper-sprayed him.

Douglas is disgusted, furious. I ask him how it’ll feel after he’s inaugurated, if and when someone else dies in there, or the county is made to pay for its violence against a future detainee, and reporters or members of the activist base from which he’s risen call him demanding answers. He tells me local officials are already advising him to not talk openly to the media, because too much sunlight could expose him or the county to liability.

“I’m not going to cost the county anything,” Douglas tells me. “What actually happened is what’s costing the county money.”

He continues, “I’ll lose this job and they can sue the hell out of me, if that’s the consequence of being honest and transparent. Let’s be honest: the county just paid a family $4 million because they murdered somebody. If that happens again on my watch, I’m going to want to say a lot.”

Stay up-to-date

Now is the best time to support Bolts

NewsMatch is matching all donations (up to $1,000) through the end of the year. Support our nonprofit newsroom today.