Six States Are Voting on Legalizing Weed or Psychedelics

Your guide to drug referendums in the 2022 midterms

Alex Burness | October 13, 2022

It’s only been ten years since voters in Colorado and Washington State legalized recreational marijuana. Those were national milestones at the time, but others quickly followed; recreational marijuana is now legal in seventeen more states, and the November midterms could expand that map further, potentially bringing legal marijuana deeper into conservative areas.

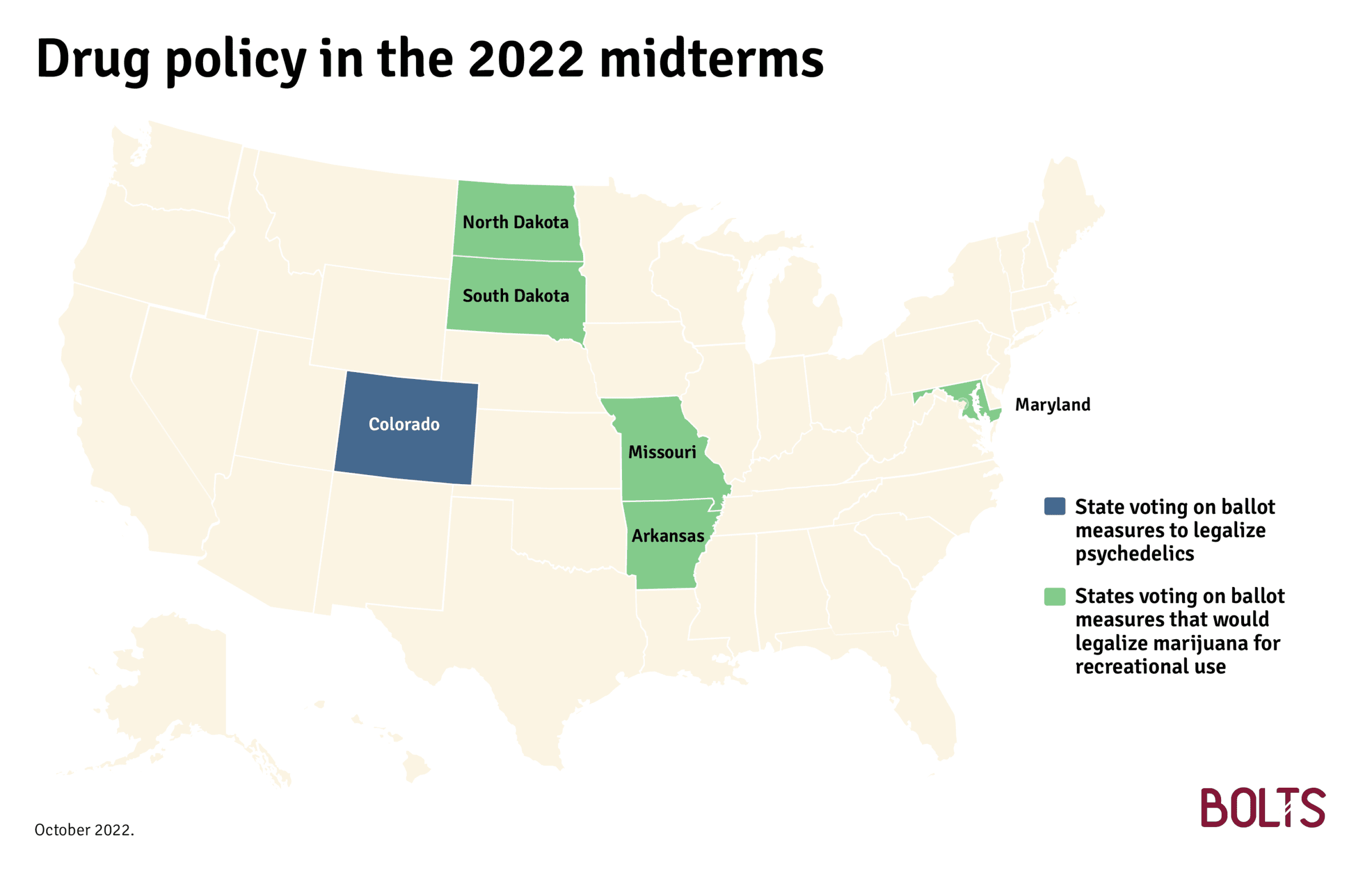

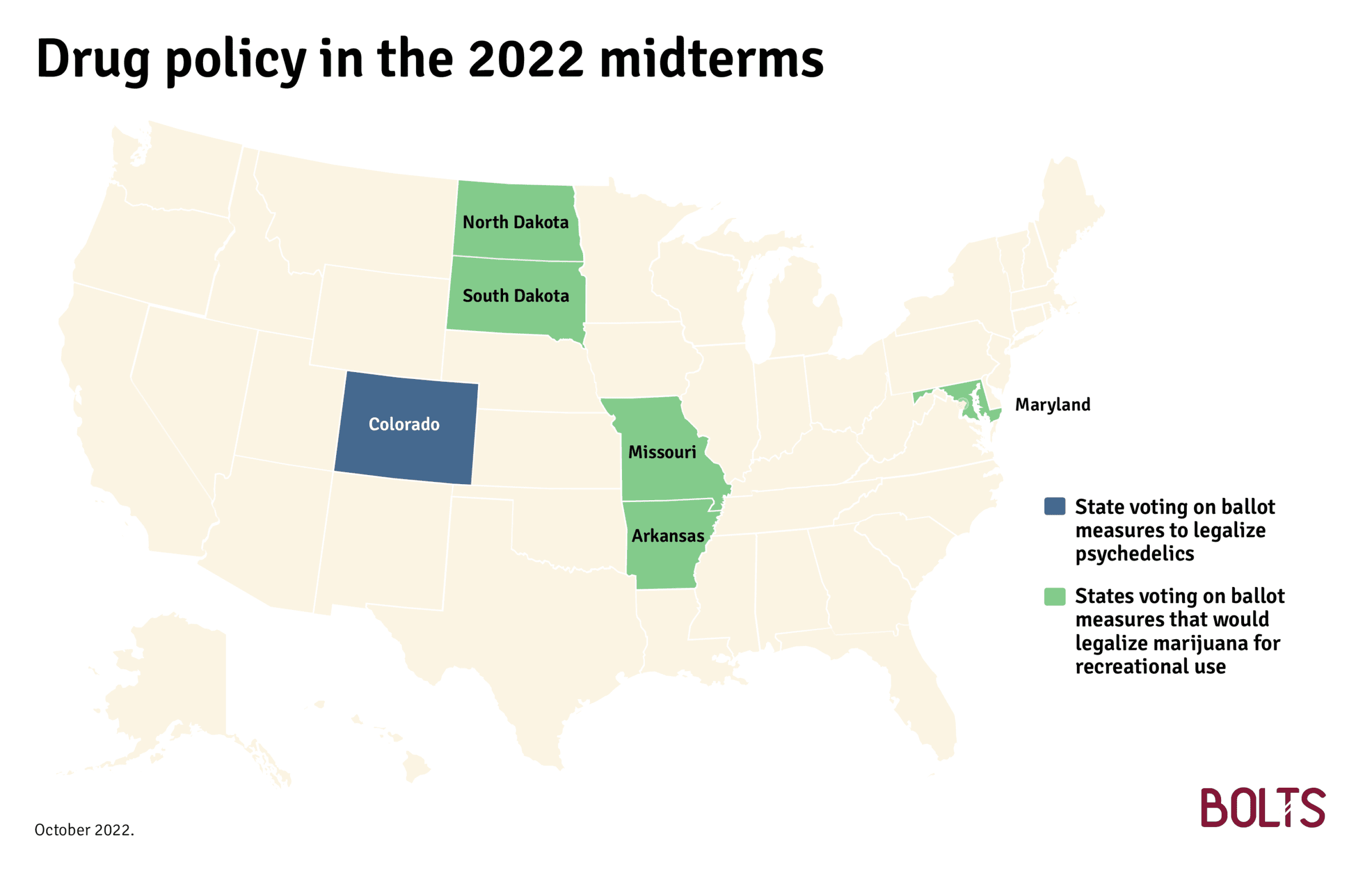

Five states are voting on legalizing recreational marijuana, and most are staunchly Republican. The issue has long drawn support across the political spectrum, and these elections will again test the sense of a growing national consensus against marijuana prohibition.

Even President Biden, who was a dedicated soldier in America’s war on drugs while a senator, is coming around. Last week he ordered a federal review of marijuana’s classification as a “Schedule 1” substance, defined as having h “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse,” and he pardoned an estimated 6,500 people with federal convictions for marijuana possession, plus thousands more convicted in the District of Columbia.

The national debate over the war on drugs is also shifting past marijuana. Colorado, which helped launch the wave of weed legalization a decade ago, is now considering a measure that would legalize psychedelics, emulating a reform adopted by Oregon in 2020.

Bolts looks at the six state referendums, plus some intriguing local measures, that may affect drug policy this fall.

Most measures would establish new state-regulated systems for the sale of marijuana or, in the case of Colorado, psychedelics, likely bringing in considerable new revenue into public coffers.

But there is wide variance as to how they would handle people who have already been convicted over behaviors that could soon become legal. A review by Bolts shows that only two of the five marijuana referendums would set up expungement of past criminal records, which considerably saddle a person’s access to jobs and housing.

Arkansas | Issue 4: On legalizing marijuana

Arkansas could become just the second state in the South, after Virginia, to legalize marijuana for recreational use and sales. Issue 4 qualified for the ballot after a petition drive organized by the group Responsible Growth Arkansas, just six years after another citizen-initiated measure legalized medical marijuana. A September poll found wide support for the measure.

But Issue 4 is also raising concerns about inequitable design. The Arkansas Advocate found that Arkansas would have the strictest rules among the 19 states that have legalized recreational marijuana: It would be the only one to both prohibit home-grow operations and keep a hard cap on cultivation and dispensary permits, which experts predict would limit supply and competition, leading to higher prices at retail stores. A more exclusive market could also perpetuate race and class disparity in who has access to the substance, and who is policed over it.

Moreover, unlike in some of the other states with marijuana measures this year, Issue 4 does not provide for wiping clean the criminal records of people already convicted over marijuana.

Republican lawmakers are angry that organizations are using the initiative route to champion issues that they oppose, including the 2016 medical marijuana vote. They have placed another measure on the ballot that would make it harder for ballot measures to pass in the future.

Missouri | Amendment 3: On legalizing marijuana

Just north of Arkansas, Missouri has also legalized marijuana for medical use, and may now do the same for recreational use.

Amendment 3, which also qualified for the ballot through a petition drive organized by the group Legal Missouri, would end existing state prohibitions on the possession of marijuana, set up a regulated sales system by distributing licenses via a lottery system, and allow home growth. Polling shows a closely divided electorate.

Missouri borders eight states, only one of which (Illinois) has legalized recreational marijuana. Based on the experience of other states, that would presage an influx of out-of-state customers looking to buy legal marijuana in Missouri. But this could also cause new legal problems as these customers would be breaking the law the second they crossed back into their home states, where marijuana possession may be punishable by jail time. This has been a long-documented problem for people traveling into Kansas with weed from Colorado.

The Missouri amendment creates a path for people with marijuana convictions to expunge their records. But many marijuana advocates believe the ballot measure does not go far enough and are raising alarms. They stress that some people would be excluded from automatic expungement due to carve-outs or because they’re still serving time; they also note that the initiative would keep in place some criminal penalties, including for smoking marijuana in public. The chair of Missouri’s Legislative Black Caucus opposes Amendment 3 on these grounds. Organizations that support criminal justice reforms such as ACLU of Missouri and the Missouri Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, are supporting it.

Maryland | Question 4: On legalizing marijuana

Going off of the results of the last presidential election, Maryland is the bluest state in the country that has yet to legalize marijuana. Question 4 would end that distinction and legalize the possession and retail sale of marijuana.

Maryland lawmakers placed it on the ballot as a constitutional amendment that does not need the governor’s signature. (Republican Governor Larry Hogan has vetoed bills related to marijuana in the past.) Lawmakers also passed implementing legislation earlier this year (House Bill 837) that would be triggered by the passage of Question 4; Hogan allowed the bill to become law without his signature.

The legislation would automatically expunge the records of people who have been convicted of offenses that would be newly legal under the law. It would allow people who are presently incarcerated for marijuana possession to petition for immediate release.

If Question 4 passes, lawmakers would still have a lot of blanks to fill in the next session, as HB 837 did not flesh out the regulatory details of marijuana sales. Progressive advocates and lawmakers have already signaled that building an equitable retail system is a prime concern and that they want dispensary licenses and tax revenue to be distributed in a way that helps the Black communities that have been disproportionately affected by the prohibition of marijuana. A report released by the Baltimore prosecutor’s office in 2019 found that Black residents of Baltimore were six times likelier than white residents to be cited for marijuana possession.

North Dakota | Measure 2: On legalizing marijuana

North Dakotans overwhelmingly rejected a measure to legalize marijuana just four years ago. But proponents of legalization are hoping for a different outcome by highlighting a broad alliance: Measure 2 qualified after a petition drive organized by a coalition called New Approach ND, whose chair is a member of the Libertarian Party and whose treasurer is a police officer-turned-defense attorney. The measure’s sponsoring committee features lawmakers from both parties.

The Republican-run state House already passed a legalization bill in 2021, though the bill later died in the Senate. Measure 2 picks up where that bill left off: It would legalize the possession and sale of marijuana, and also allow home growth of up to three plants.

The measure would leave a lot of regulatory rulemaking for the legislature to take care of, but it does stipulate that only 18 retail licenses would be granted to start. That may limit the circulation of marijuana in a very vast, if sparsely populated, state.

Measure 2 would not allow for expungement of criminal records, unlike the 2018 measure that provided for automatic expungement.

South Dakota | Measure 27: On legalizing marijuana

South Dakotans already said what they think about marijuana in 2020: 54 percent of voters approved a ballot measure to legalize its recreational use. But after a lawsuit championed by Republican Governor Kristi Noem, that measure was invalidated by the South Dakota Supreme Court the following year for breaching the state’s requirement that initiatives only pertain to one subject.

Advocates returned this year with a drive to qualify a new proposal for the ballot. Measure 27 takes a simpler approach than the 2020 initiative. It would not change the state constitution, for one. It would allow for the purchase and possession of marijuana, plus home-grows of up to three plants for personal use, but it would leave questions of taxation and regulatory structure to the state legislature.

And it would not set up a process for people to expunge their past convictions.

The marijuana debate has seeped into the governor’s race, as Democratic nominee Jamie Smith has denounced Noem’s efforts to overturn the 2020 initiative. Another South Dakota election that touches on drug policy is the ballot measure to expand Medicaid access to tens of thousands of people; enhanced health insurance can improve paths to treatment over substance use issues that are otherwise funneled into jail, which played a role in other recent referendums over Medicaid.

Colorado | Proposition 122: On legalizing psychedelics

With Proposition 122, a voter-initiated measure once known as Initiative 58, Colorado may add to a new trend: Building off of a 2019 ballot measure in Denver, and a 2020 ballot measure in Oregon, the measure would remove criminal penalties for use, possession and home-grow of psilocybin (commonly known as “magic mushrooms”) and some other psychoactive substances.

It would also set up a legally regulated system for state-regulated providers to sell psychedelics for a range of treatment and therapeutic purposes.

Denver, the state’s capital city, did a version of this, and a government review panel that included law enforcement found no resulting threats to public safety. Some of the organizers of the Denver reform are now opposing Initiative 58 because they fear the measure would specifically benefit a small handful of profit-seeking interests. “It’s opening the floodgates for corporations to come to Colorado to open their bougie life and healing centers,” one advocate who worked on Denver’s decriminalization effort told The Denver Post.

Local elections matter to drug policy, too

Under the hood of state statutes and prohibitions, localities retain vast powers to decide how aggressively to pursue the war on drugs. That, too, is at stake this year all around the country.

Colorado, for instance, is a home-rule state, meaning that towns and counties still have the authority to ban the sale of marijuana. Colorado Springs, the state’s second-largest city and the anchor of a historically arch-conservative region, has long resisted legal weed; residents cannot purchase it within the city, which misses out on all the local sales tax that other municipalities get to collect. Colorado Springs voters this year will decide Questions 300 and 301, which would enable recreational marijuana sales and tax them.

In Texas, where marijuana is illegal but where some liberal-leaning cities have asked the police to not enforce the statute, some towns like Killeen will weigh in on decriminalizing marijuana.

And the war on drugs is also on the ballot in many elections for the law enforcement offices that have the power to make arrests or press charges over drugs—or refuse to do so. In many places, the debate still revolves around marijuana. The Democratic incumbent in Indiana’s Marion County (Indianapolis), for instance, has stopped prosecuting low-level possession but his Republican challenger is taking issue with that. “I do not want Indianapolis to become a San Francisco, to become a New York City, to become a Los Angeles,” she said at a recent forum.

Other candidates are promising to at the very least avoid jail time over drug offenses. And some reformers want to go further and keep the criminal legal system out altogether. Rahsaan Hall, running for prosecutor in Plymouth County, Massachusetts, says he won’t prosecute drug possession. “Those are not law enforcement issues,” Caitlin Sepeda, a nurse who narrowly lost the primary for sheriff in another Massachusett county in September, told Bolts last month. “Those are nursing issues. Those are social service issues.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.