Floridians Restricted Gerrymandering. Their Justices Are Retreating on Enforcing That.

Florida’s supreme court blessed the 2022 GOP gerrymander, weakening a key provision of the voter-approved Fair Districts Amendments. Governor DeSantis wants to take advantage.

| August 12, 2025

Just weeks after Florida’s Supreme Court weakened voter-approved restrictions against gerrymandering, Governor Ron DeSantis is already pushing to take advantage of the new ruling.

Fresh off a 5-1 Supreme Court win in his pocket, DeSantis announced plans to redraw Florida’s congressional map again, well before the next census. “Stay tuned,” DeSantis teased at a press conference outside of Tampa in late July.

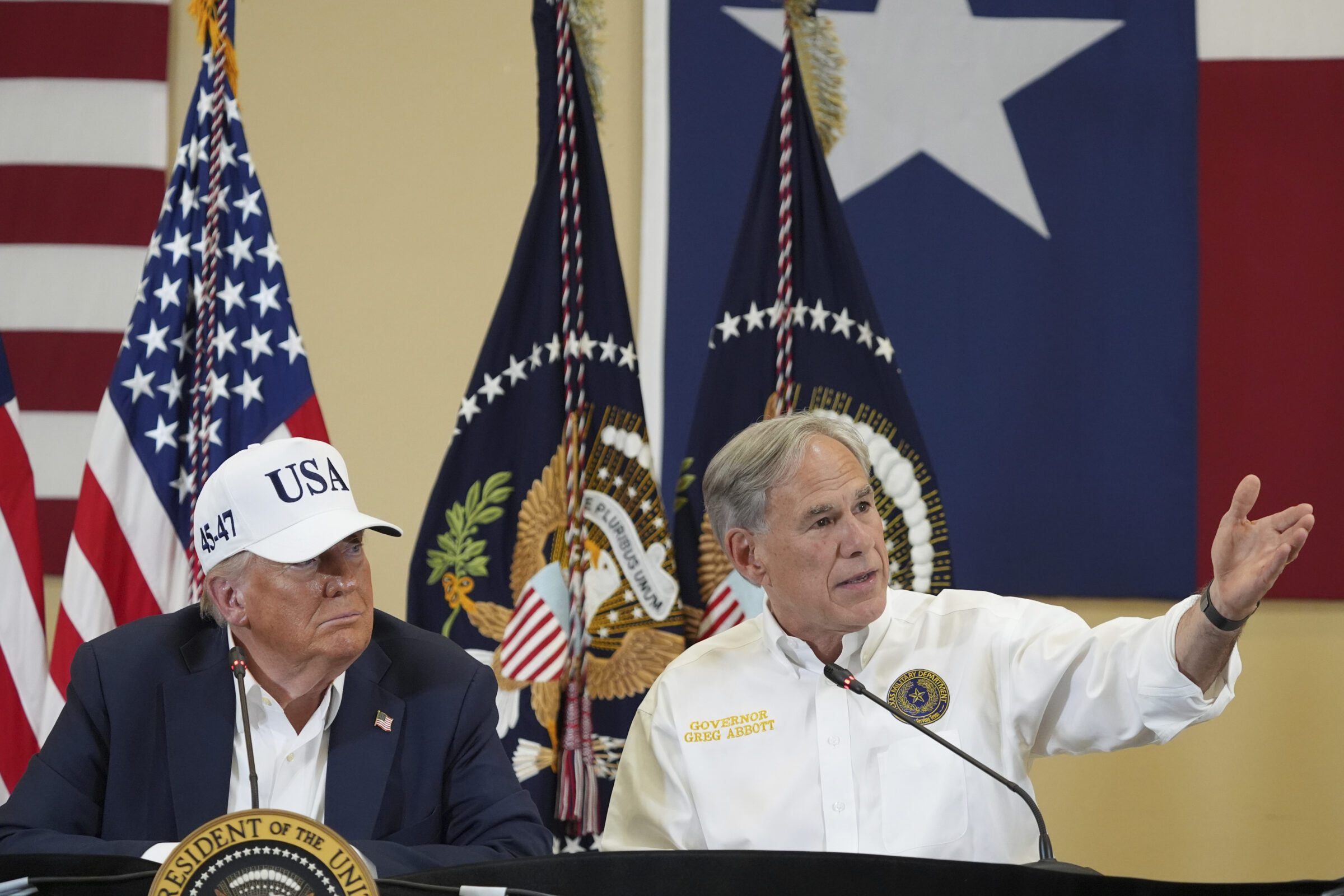

The push is already underway, adding to a national effort by the GOP, in full swing in Texas, to lock in more seats before the midterms. Florida House Speaker Daniel Perez said he will name the members of a new redistricting committee next month.

Even if Republicans forgo a new map this year, the ruling locks in Florida’s existing gerrymander, and it’s likely to embolden the GOP whenever it next redistricts the state.

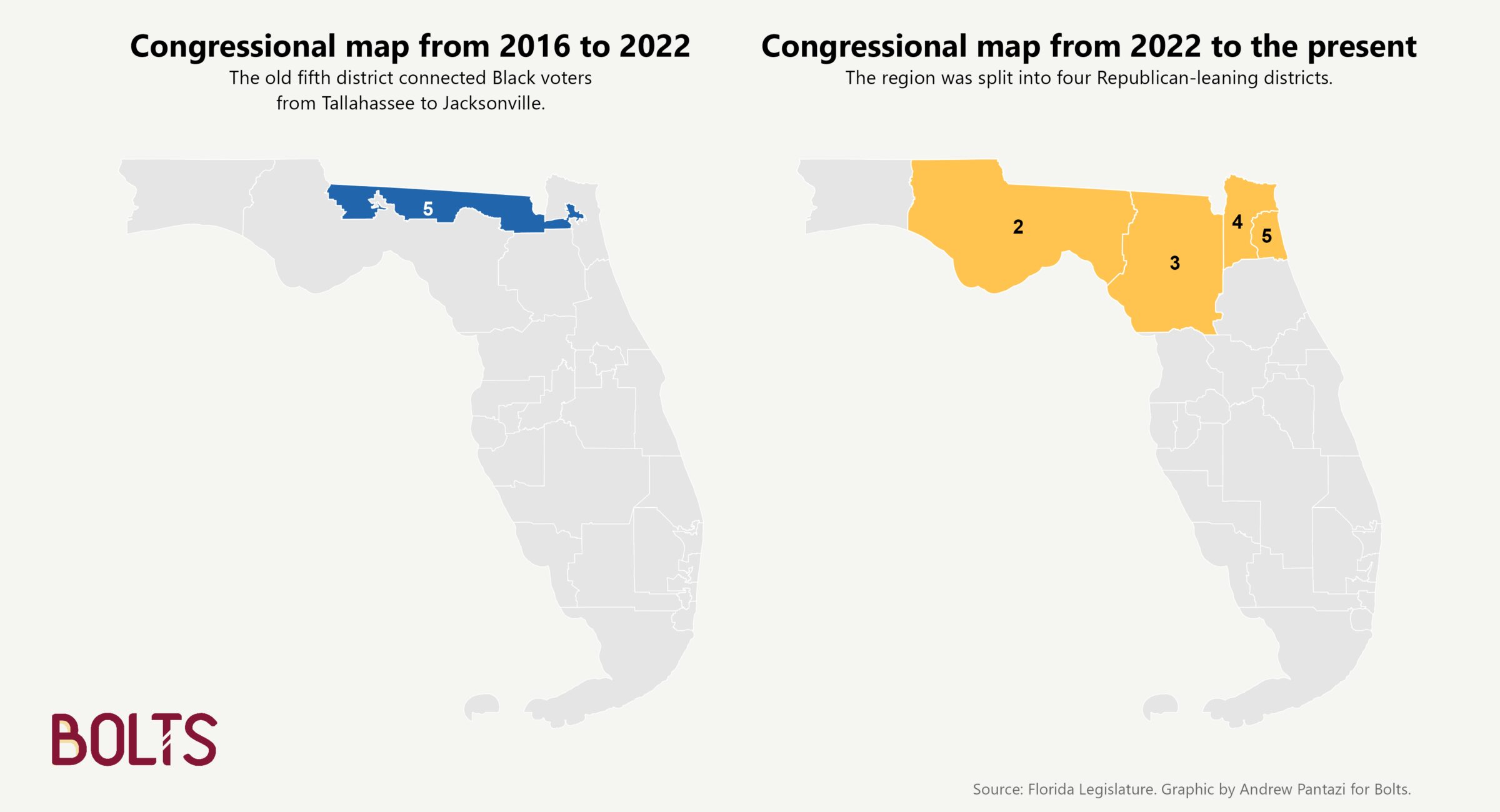

The court blessed DeSantis’ 2022 push to dismantle a North Florida district where Black voters had consistently elected their preferred candidate for three decades.

More than that, the justices signaled a retreat in their willingness to protect Black voting power with the Fair Districts Amendments, a set of standards approved by voters in 2010.

The court’s opinion pared down a key anti-gerrymandering protection, known as non-diminishment, which bars reducing a minority community’s ability to elect its candidate of choice.

“The opinion is not nearly as bad as it could have been,” said Chris Shenton, a voting rights lawyer with the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, who stressed that it preserves some legal paths for plaintiffs to target Florida’s political maps in the future. But, he added, it provides cover for Florida politicians who want to ignore some of the state’s anti-gerrymandering rules.

“It dramatically empowers the Legislature to decide when it wants to be bound by anti-discrimination protections,” Shenton told Bolts.

A court transformed

Championed by a bipartisan coalition and approved by more than 63 percent of voters in 2010, the Fair Districts Amendments were designed to stop politicians from drawing biased maps. They banned partisan gerrymandering and required compact districts that didn’t unnecessarily split cities and counties.

Crucially, this reform also copied two protections from the federal Voting Rights Act. The first, modeled off of Section 2 of the VRA, prevents map-drawers from locking a minority group out of electing their candidates of choice, which can happen when a community that is populous and compact enough to form a majority is instead spread across other districts. The second, non-diminishment, is based on Section 5 of the federal law.

Back in 2015, Florida’s supreme court ordered lawmakers to redraw eight congressional seats, saying they were drawn to favor Republicans. “The court has made it abundantly clear that partisan gerrymandering will not be tolerated,” an attorney for the plaintiffs said at the time.

But this court has transformed since then. Once a progressive check on state policies, the court is now a conservative weapon remade by DeSantis. All seven justices are Republican appointees, five chosen by DeSantis himself.

In challenging the 2022 congressional map, plaintiffs braced for a more skeptical court and narrowed their complaint. They agreed to forgo a trial, dropped partisan gerrymandering claims and focused their lawsuit on what felt like the safest legal ground: that the map violated non-diminishment protections by splitting Black voters from Jacksonville to Tallahassee into four Republican districts, wiping out the region’s only Black-represented seat in Congress.

The gamble failed.

Even though the state admitted it had reduced Black voting power, the court’s conservative majority declared the very district it ordered into existence a decade ago to fix partisan gerrymandering was, in fact, an unconstitutional racial gerrymander.

The majority wrote that “there is no plausible, non-racial explanation for using a nearly two-hundred-mile-long land bridge to connect the black populations of Jacksonville and Tallahassee.”

As a result, Black voters in Jacksonville remain cracked into whiter, more Republican districts, as they have been since 2022.

Drawing a more Republican-favoring map could also invite a new lawsuit under the Fair Districts Amendments’ anti-partisan gerrymandering standards, which remain intact from last decade, though plaintiffs would have to brace for their complaints to be reviewed by conservative justices.

Still, Shenton and others said the Fair Districts Amendments could have fared even worse. The nightmare scenario, Shenton explained, was the court striking down the protections entirely. “I think what a lot of us were bracing for was a holding that the Fair Districts Amendments are facially unconstitutional… that it’s just not enforceable,” he said. “They didn’t do that.”

Instead, the court left the amendments on the books, but created a legal Catch-22 that severely weakens them.

To prove a map illegally diminishes minority voting power, challengers now face a new burden. According to the court, challengers must show they can draw a replacement district without race being the predominant factor.

In other words, to stop politicians from harming minority voters, plaintiffs must first create a fix that wasn’t primarily designed to help them.

The new standard mirrors what some conservatives unsuccessfully sought from the U.S. Supreme Court in the Allen v. Milligan case out of Alabama: protections for minority voters technically exist, but only if you can prove districts weren’t drawn mainly with race in mind, a paradoxical standard that few maps could ever meet.

Justice Jorge Labarga, the lone dissenter in the Florida supreme court’s July ruling, warned that the decision “lays the groundwork for future decisions that may render the Non-Diminishment Clause practically ineffective or, worse, unenforceable as a matter of law.”

The court also suggested the legislature could justify drawing a race-conscious district if it assembled “a fresh evidentiary record” of discrimination, a power it did not extend to plaintiffs.

When Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, it assembled a massive legislative record documenting decades of systematic discrimination against Black voters across the South, with thousands of pages of testimony, statistical evidence, and historical documentation that justified race-conscious remedies nationwide.

Florida’s Supreme Court essentially ruled that lawmakers must assemble a similar record, starting from scratch every single time they want to draw race-conscious districts.

Under this new standard, the legislature would need to compile fresh evidence of discrimination for each individual district, treating every application of the constitutional protection as if it were the first. The court created a system where citizen-passed anti-discrimination protections carry less weight than federal law, requiring constant re-justification of remedies that the amendments were designed to make routine.

“That’s really novel,” Shenton said. “There’s never been an anti-discrimination statute that has required you to assemble an evidentiary record to justify each use of that law.”

The new bar set by the court will likely deter future lawsuits, effectively making the constitutional protection a dead letter, he warned. “If you have to assemble a record every time you want to seek its protections,” he said, “you’re going to end up with a law that’s not used very often.”

How the GOP could squeeze out more seats

While the court didn’t formally strike down the Fair District Amendments, DeSantis has reacted as though Republicans no longer need to bother with the protections. He said the opinion assured him the courts wouldn’t enforce the standards and predicted the courts would eventually find them unconstitutional.

House Speaker Perez wrote in a memo to legislators that the ruling presents an “opportunity” to explore “important and distinct questions” about the “so-called ‘Fair Districts’ provisions of the Florida Constitution.”

Observers expect Republicans to target the Orlando-area seat held by Democrat Darren Soto, as well as several South Florida districts, including those held by Democrats Jared Moskowitz, Lois Frankel, and Debbie Wasserman Schultz, the former chair of the Democratic National Committee.

Yet some experts are skeptical that Republican gerrymanders of Florida can go much further.

A 2023 peer-reviewed study ran thousands of computer simulations and found that Florida’s map is already the second most skewed toward Republicans in the country, beaten only by Texas.

The current plan is so gerrymandered that not one of 5,000 simulated maps gave Republicans a bigger advantage.

“I don’t see where he’s going to carve out additional seats,” said Daniel Smith, the University of Florida’s political science chair.

The more competitive Democratic districts in South Florida are surrounded by even bluer territory, so it could be challenging to draw them to be significantly more Republican. And breaking up the packed Democratic districts could accidentally help Democrats in surrounding seats, Smith pointed out.

Many lawmakers remember the bruising 2015 court-ordered redraw and, if DeSantis calls a special legislative session, they may prefer to “gavel in and gavel out” rather than reopen battles that could backfire, Smith suggested.

The GOP’s most obvious target, the Orlando-area Ninth District, is a fast-growing, majority-Hispanic district. Breaking up that district could invite a tough lawsuit under the Voting Rights Act, since the district is extremely compact and majority Hispanic.

Instead of trusting courts to review lawmakers’ work and enforce anti-gerrymandering protections, said Quinn Yeargain, a law professor at Michigan State University and frequent Bolts contributor, reformers last decade could have pushed for a nonpartisan redistricting commission.

But even that federal protection is under fire, as the U.S. Supreme Court is set to hear a case out of Louisiana this fall that could further weaken the VRA.

He pointed to California where a durable, voter-approved commission has made it more difficult for Democrats in other states to retaliate with gerrymanders of their own. California Democrats are still planning to respond to Texas’ redistricting by asking voters to temporarily overturn the independently drawn map.

“It always really struck me to be political malpractice that nobody tried in earnest with any good amount of money to put a non-partisan redistricting commission on the ballot in Florida.” But Florida reformers counted on the courts to enforce anti-gerrymandering protections. Fifteen years later, Yeargain said, it’s clear that strategy “has failed.”

Florida justices have instead given Republican lawmakers a roadmap for working around those reforms. What seemed like durable constitutional safeguards now depend largely on the restraint of the very politicians they were designed to constrain. That, Shenton said, is “a really perverse result for a constitutional amendment that was designed to take this power out of the legislative hands.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.