Six “America First” Candidates, Vying to Take Over Florida Elections, Advance to November

Prominent election deniers are supporting a slate of Florida Republicans who are running to lead local election offices. But roughly half of the slate lost in Tuesday’s GOP primaries.

| August 23, 2024

Editor’s note (Nov. 7): Members of this coalition won the general elections in Monroe and Seminole counties, and lost in the other counties in which they were running.

Followers of Donald Trump are pursuing an unusually coordinated effort to capture local election offices in his home state of Florida. Still motivated by his false claims of widespread voter fraud, they have formed a slate of self-described “America First” candidates and they’re running this year to take over as their county’s supervisor of elections for the four coming years.

Jeff Buongiorno, a slate member in Palm Beach County, has called elections in Florida “a conspiracy from the top down,” alleging that the state’s GOP leadership is enabling noncitizens to vote. Chris Gleason, the candidate in Pinellas County, has baselessly claimed that the local supervisor, Republican Julie Marcus, had made Pinellas “ground zero” of mail voter fraud.

The candidates hail from different corners of the state but many have held joint events and press conferences and they’ve appeared on podcasts as a group to air their grievances. “Every single one of them is running because they saw their local SOE not following election law properly or not maintaining their voting rolls, and they got really upset,” Cathi Chamberlain, who is loosely coordinating this coalition of 13 candidates and is the founder of Pinellas Watchdogs, a group that circulates fringe theories about fraud, said on a right-wing podcast in July.

The group hit a wall in Tuesday’s GOP primaries.

Six of its members were defeated by incumbent Republican supervisors, including Gleason in Pinellas County. A seventh candidate trailed in his primary’s initial count.

But elsewhere in the state, six more coalition members, including Buongiorno, are advancing to the general election. They’ll continue their bid to take over supervisor offices into November.

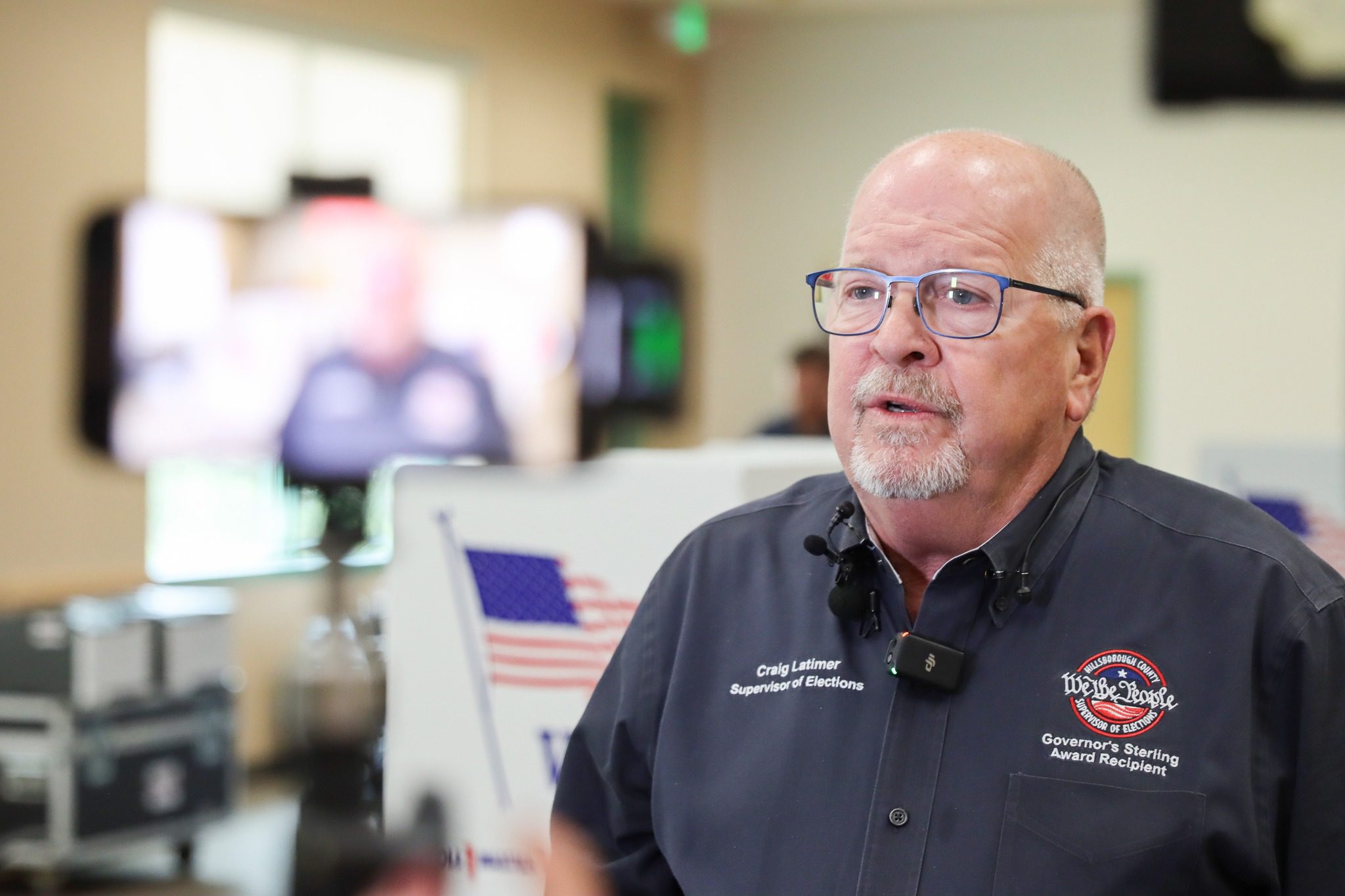

“Many of my colleagues have been worn down by the atmosphere we find ourselves in but it has only strengthened my resolve,” incumbent Hillsborough County Supervisor of Elections Craig Latimer, a Democrat who’ll face slate member Billy Christensen in the fall, told Bolts.

Christensen was unopposed in Hillsborough County’s Republican primary. He’s one of four slate members who moved to November with no intraparty competition, alongside the candidates in Alachua, Palm Beach, and Osceola counties. Alachua is staunchly blue. Hillsborough, Palm Beach, and Osceola all flipped from voting for Democrat Joe Biden in 2020 to voting for Republican Ron DeSantis in 2022.

Two other coalition members moved forward after winning contested GOP primaries in Monroe County and Seminole County. Both will also face Democrats in November.

Slate candidates lost, often by overwhelming margins, in Pinellas, Charlotte, Collier, Lake, Lee, and Santa Rosa counties. In St. Lucie County, a manual recount is expected to stretch into next week; it’ll decide whether coalition member George Umansky, who trailed by just two votes in the initial count out of roughly 25,000 cast, moves on to face Democratic Supervisor Gertrude Walker. (Editor’s note: The recount confirmed that Umansky lost the primary to Republican Jennifer Frey by four votes.)

“We are extremely concerned that people trying to shake the public’s trust in elections are seeking to run our elections,” said Brad Ashwell, the state director for All Voting is Local, a nonprofit organization that works to make it easier for marginalized communities to vote.

“Voters saw through the lies and voted down a lot of these candidates,” Ashwell said of Tuesday’s results. “We are really hopeful the other candidates moving into the general see those losses and realize it is not a winning strategy.”

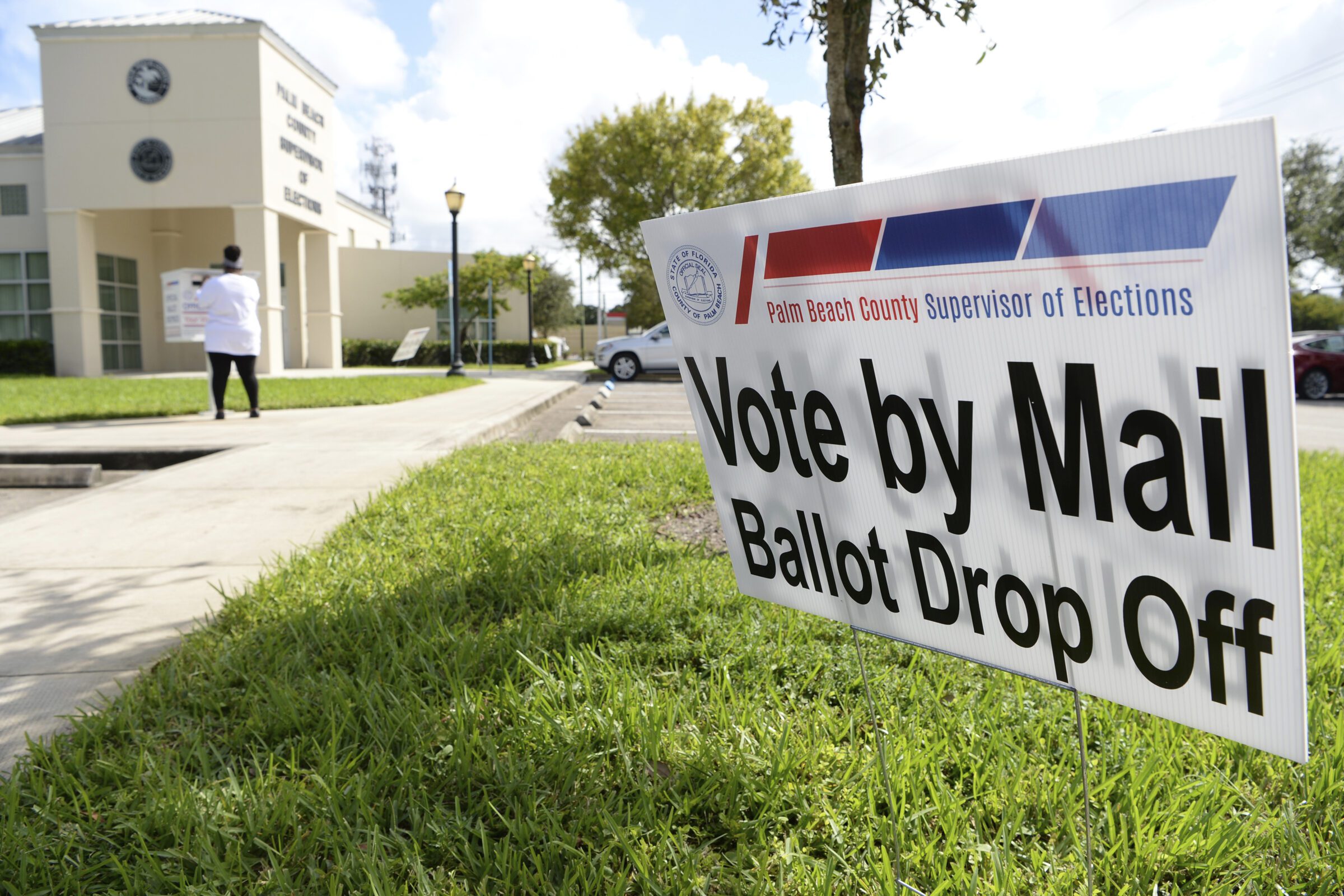

Supervisors of elections in Florida are responsible for running elections within their county; they oversee voter registration, design ballots, conduct voter outreach, and process mail ballots.

They can’t unilaterally change election rules set by lawmakers and the secretary of state. So the slate’s candidates wouldn’t have the authority to execute the changes some of them are proposing, such as ending the use of voting machines or banning all mail voting.

Still, Ashwell warned, county officials would have opportunities to upend the system. They may grow more aggressive in purging registered voters based on minor errors on their forms, rejecting more mail ballots based on technicalities, and using dodgy AI tools to chase down issues on voter rolls. A far-right group has been pressuring local election officials to purge voters based on lists generated by the tool Eagle AI, which scrubs voter rolls to identify inconsistencies with other public databases; the state’s top elections official encouraged local offices to “take action” based on those lists, but voting rights advocates warn that these lists are not reliable.

Counties also have a lot of discretion on how accessible to make voting—how many drop boxes to install, how long early voting locations are open. And some slate members signaled they’d curtail access. “‘Easy to Vote’ MEANS ‘Easy to Cheat,’” their candidate in Lake County, who lost on Tuesday, wrote on his website.

No supervisor can single-handedly refuse to certify their county’s election results, but they all sit on the three-person body responsible for certification.

Some of the slate’s candidates have drawn support from prominent figures who support election denier networks, such as Mike Lindell, the CEO of MyPillow, and billionaire Richard Uihlein.

But not all thirteen candidates align on what took place in the 2020 election, and whether there’s widespread fraud within Florida—or only in the states that Trump lost.

Several slate candidates have asserted without evidence that Florida officials are erasing tens of thousands of votes. Others like Sherri Hodies, who won an open GOP primary in Monroe County, home to Key West, have said they trust Florida but believe there are issues with the count in Michigan or Georgia, states where Trump has denied his 2020 losses.

Meanwhile, Amy Pennock, the slate’s candidate in Seminole County, told the Miami Herald that she does not think the 2020 election was stolen.

Pennock, who did not respond to a request for comment, is the only slate candidate who beat an incumbent in Tuesday’s Republican primary. She ousted Chris Anderson, whose tenure involved major clashes with the county’s other GOP officials. Anderson, who is Black, said last year that he was encountering racial discrimination that was making it harder for him to do his job. And he accused members of the county commission of racism in a social media video. Anderson also faced a complaint this month for allegedly using his role as supervisor to boost his own campaign, but a judge tossed the claim after finding no evidence.

Pennock, a conservative member of the county school board who last year proposed to review and restrict access to some books in public school libraries, will now face Democrat Deborah Poulalion in November.

Poulalion told Bolts that she worries that misinformation about election fraud could weaken the security and accessibility of Florida’s voting system. “One of the worst things that came out of 2020 was losing confidence in the integrity of the system,” she said. “I think the system is still working, but the lack of confidence in the system could lead to making changes that make the system less effective.”

Since the 2020 election, DeSantis and Republican lawmakers extensively restricted Florida’s voting laws, ostensibly to boost voters’ confidence. They toughened voter ID requirements, made it harder to vote by mail, and have set up a new police force to investigate fraud.

Lake County Supervisor of Elections Alan Hays, a Republican who defeated a slate candidate on Tuesday, told Bolts that he is satisfied by the result of his own primary. But he regrets that a lot of harm has already been done to the state’s voting systems.

“I certainly think it is a rebuke of the nonsense that has been spread,” he said of Tuesday’s results. “Unfortunately, we’ve had too many legislators already listen to the garbage that has been voiced by this side of the equation. That’s why some of the election laws have been modified the way they have.”

Hays is part of the Florida Supervisors of Elections, a professional membership organization that lobbies state lawmakers on behalf of local elections officials. The organization has worked to dispel misinformation and fight proposals that risk jamming up the election process. Hays, for instance, has spoken out against proposed legislation that would allow local officials to count votes by hand rather than use machines. This has become a rallying cry for conservatives who doubt election results, despite evidence that hand counting is error prone and expensive.

“Our association has been very active and we have been able to help craft the legislative changes so they are not as offensive as they would have been,” Hays told Bolts.

But Ashwell worries that, if more election deniers took over as local supervisors, they may use the association as a platform to advocate for statewide changes.

“When we have more and more of these election denial candidates winning races, it changes the tenor of the association,” Ashwell said. “If they change the willingness of that association to weigh in on a bill to allow hand counts, then that could become standard in Florida.”

Christensen, the “America First” coalition’s candidate in Hillsborough County, told Bolts that he is eager to change the politics of the statewide association. He thinks the group has a thumb on the scale, and is weakening trust in elections by failing to address issues.

Picking up a key conservative grievance about the 2020 election, Christensen has blamed Latimer, the Democratic incumbent, for accepting a large grant to help run elections that year from a nonprofit organization with ties to Mark Zuckerberg, the founder of Facebook. These grants were distributed to thousands of election offices nationwide, but Trump-aligned conservatives have pointed to them to make unfounded claims that local election offices conducted inappropriate activities that year.

Florida and dozens of other GOP-run states have banned private grants to election offices since 2020. Florida supervisors’ professional association successfully lobbied in 2021 to water down that legislation, fearing that it’d leave them cash-strapped and needing to cut crucial operations.

But Christensen also says it was a local issue, rather than presidential headlines, that led him to run for office. His family was affected by a data breach at the Hillsborough County supervisor of elections office; the county disclosed last year that a hacker accessed the driver’s licenses and social security numbers of about 58,000 residents. Latimer sent notifications to people impacted by the breach: The county’s voter registration database and tabulation system had additional security protections and were not affected, according to Latimer’s office.

Christensen casts the breach as an example of security gaps that make the county vulnerable. “When there are challenges, why is there a resistance to implementing new rules to address those challenges, for the betterment of everyone?” he asked.

He said he’d allocate more of the office budget to security, and that he wants to “run audits locally” of the county’s elections. Following the 2020 election, conservative activists nationwide have demanded audits of local election systems. In Florida, Trump’s allies called for a forensic audit of the 2020 results, but DeSantis refused to organize one, angering the former president; some members of the “America First” slate, like Alachua County’s Judith Jensen, want to organize hand audits of future elections.

Latimer told Bolts that Christensen’s statements about the breach are an “outright lie and a completely irresponsible attempt to instill fear among our electorate.” He said, “It was a basic network intrusion that was discovered and contained quickly, before it could escalate to ransomware or anything more serious.”

On Wednesday, Christensen launched a video pointing out that Hillsborough County’s elections website crashed the day before, on election night. “This incident highlights the urgent need for new leadership to maintain trust in our election processes,” he said in the video.

The websites of dozens of counties crashed on Tuesday night, a widespread outage tied to the fact that many shared the same vendor. The vendor took responsibility, saying that its systems were overwhelmed by the increased traffic of people looking for election results.

“Their technical issues didn’t slow us down or impede the results reporting at all,” Latimer said, “because I had backup plans in place. Our results were uploaded to the state, shared on social media and reported in our public Canvassing Board meeting, just as they always are. And yet my opponent immediately became accusatory once again.”

He continued, “It is absolutely critical that we have the right people in these positions to ensure that our elections continue to be run with actual integrity—and not threatened by those who don’t understand what that means.”

Hays, the Republican supervisor of Lake County who won his primary on Tuesday, agrees with Latimer; he told Bolts that the response to the crash shows how election skeptics fixate on an issue and conflate it with election fraud, with no evidence that any vote was affected.

“It had nothing to do with any malicious activity. It had nothing to do with the local county. It has absolutely nothing to do with our tabulation system,” Hays said.

“These people are blinded by their obsession and they refuse to acknowledge the facts,” Hays continued. “They don’t come up with any concrete evidence. All they bring you is hypothetical garbage. And too many people believe their nonsense.”

Editor’s note (Aug. 28): The article has been updated to include the results of the recount in the GOP primary for St. Lucie County, and a modified characterization of Amy Pennock’s proposals on public school books.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.