As Georgia Returns to Electing Its Utility Commission, Worries over Democracy Linger

A pair of races are crystallizing issues with fair representation in Georgia: officials who stay in their seats years past their term, low-turnout runoffs, and the diluted power of Black voters.

| September 16, 2025

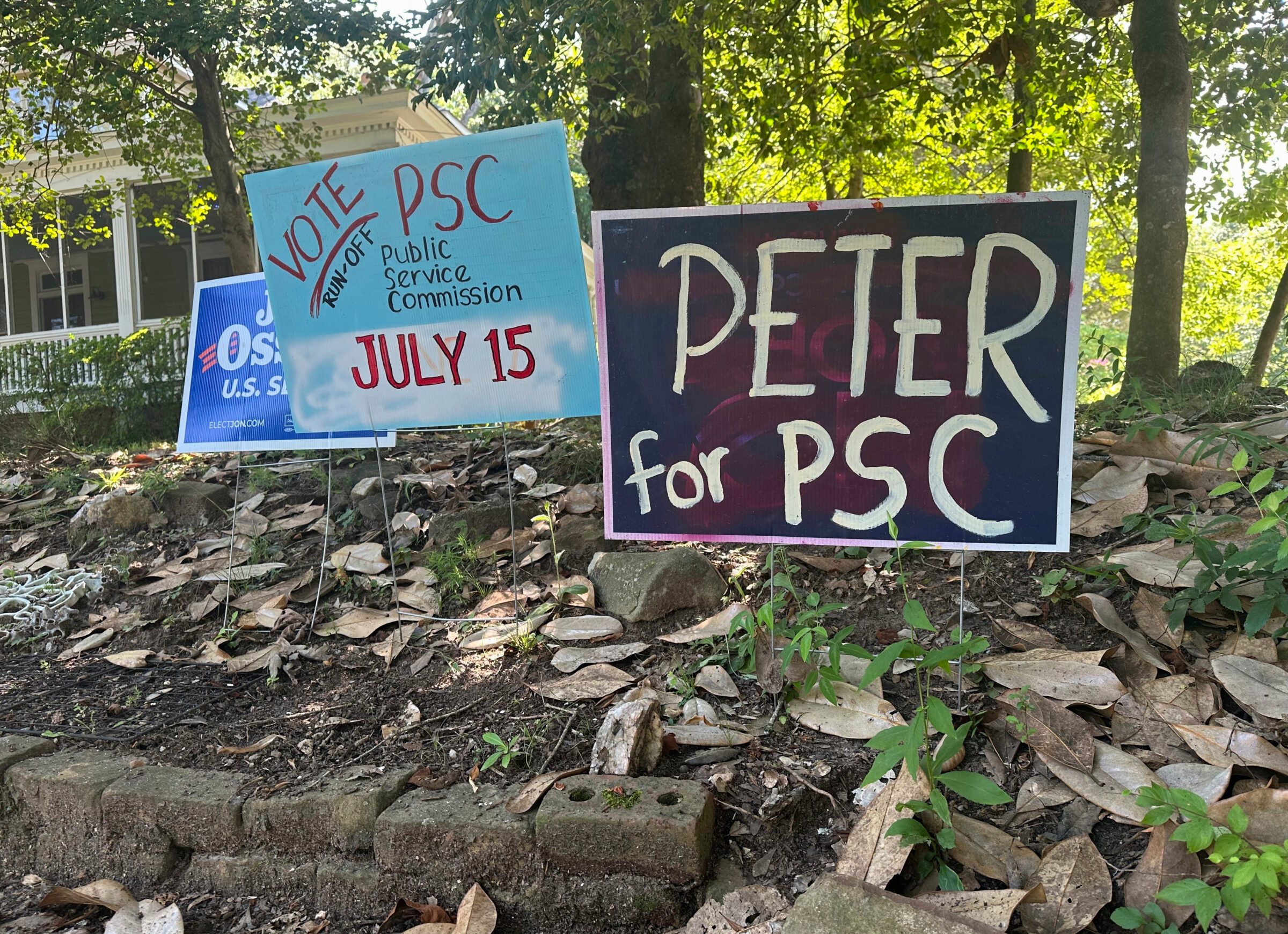

Georgia held a statewide election on July 15 of this year, but in Miller County, where just under 6,000 people live near the border with Alabama, you’d be forgiven for having absolutely no idea.

The race was a Democratic primary runoff for a seat on the Georgia Public Service Commission, the governmental body that regulates gas, electricity and telecommunications in the state, including the state’s largest electricity provider, Georgia Power. The commission approves rates that consumers pay, and it has courted controversy in recent years by repeatedly voting to increase prices for electricity. It also shapes the state’s environmental future, determining its energy mix between clean energy and fossil fuel sources.

And yet, in Miller County, a whopping eight voters turned out for the election.

Election Supervisor Jerry Calhoun wasn’t expecting much turnout. This is an area where the vast majority of residents vote Republican, and there was nothing on the ballot other than this Democratic runoff for an under-the-radar office. Still, eight voters represented a steep drop off from the roughly 160 who took part in Democrats’ last primary for a statewide office.

“The very few [voters] I had was people that came in the courthouse for other business,” Calhoun told Bolts. “They’d see our sign, and say ‘Hey! What are we voting on?’”

Forcing runoffs when no candidate gets 50 percent of the vote has been longstanding practice in Georgia, but also a controversial one, in part because it’s known to suppress turnout. Today, Georgia remains one of just seven states that requires primary runoffs if no candidate clears 50 percent; it’s one of just three that does so for general elections. Coverage of the runoff campaign this summer was widely dominated by complaints from local officials that they had to spend resources to call voters back to the polls for this one election.

And this controversy over low-turnout runoffs is just one of the many problems with fair representation in Georgia—from a pattern of canceled elections, to voting structures that have harmed Black voters—that are coming to a head in the state’s PSC elections this year.

In recent years, efforts to reform those issues have played out in courts, in the legislature, and in public opinion, but the status quo has largely won out; and now they’ve converged in the pair of races on the 2025 ballot, where the rules have angered some residents, and confounded others.

Five years ago, a group of Black voters sued to try and change how the state elects utility commissioners. Although the state is broken up into five districts, each represented by a different commissioner, all five members of the commission are elected through statewide elections. The plaintiffs argued that this at-large voting deprives Black voters from having their candidate of choice on the commission, in violation of the Voting Rights Act.

They demanded that Georgia switch to district voting, with a majority-Black district anchored in Atlanta’s metro region, where they said at-large elections had diluted the voting power of the predominantly Black population.

The multi-year legal battle that ensued ultimately had the effect of canceling all PSC elections for two consecutive cycles, in 2022 and 2024, allowing incumbents to stay in their seats, without having to face voters, long after their terms expired.

The plaintiffs won at a federal trial, but that decision was reversed on appeal, and the case eventually died last summer when the Supreme Court declined to hear it, preserving at-large elections. In the meantime, state legislators passed a law restarting PSC elections on a new schedule.

As a result, voters across the state will vote for two PSC commissioners this November. While all five seats are currently held by Republicans, Democrats could make some inroads if they can oust the two GOP incumbents who are running to stay on the panel.

Connie di Cicco, political director of Georgia Conservation Voters, the group that brought the unsuccessful lawsuit against the at-large structure, is hopeful that the general PSC elections this fall will attract more attention than usual from voters since they’re the only statewide races on the ballot.

“This election represents… an excellent opportunity for voters to have direct impact on their [electricity] bills,” she said of Georgia’s first PSC elections in five years. “When you have two PSC seats out of five come up for election, … that is real and actual hope for change. It’s more tangible than we have seen in a long, long time.”

Still, as the election machinery has now restarted after years of delay, the equity complaints that fueled the lawsuit have not been dealt with.

In fact, while the at-large voting case was still winding its way through courts, Georgia politicians adopted legislation last year to restart PSC elections, effectively ignoring the legal fight. The legislation, House Bill 1312, reset the schedule and postponed elections for every PSC seat, further extending the current commissioners’ terms by one to two years and buying them extra time before they must face voters.

After Republican Governor Brian Kemp signed it into law in April 2024, Georgia Conservation Voters joined forces with other plaintiffs to file a new lawsuit that said the law further deprived voters of choice. It argued that the terms of PSC commissioners couldn’t be extended without a constitutional amendment.

A federal district court judge dismissed this suit in early 2025, allowing HB 1312 to stand.

The law placed two commissioners on the ballot this fall, Tim Echols and Fitz Johnson. Echols represents District 2, which covers East Georgia; he was reelected to a six-year term in 2016 but hasn’t had to face voters in a general election since. Johnson was appointed by the governor in 2021 and has never faced voters; he represents District 3, which covers the Atlanta metro area. (Candidates must reside in the districts they are running for, though elections are held statewide, the unusual structure at the heart of the 2020 lawsuit.)

Echols told Bolts he saw no problem with his extended term. “I am honored to serve the citizens of Georgia as long as they will have me.”

Johnson, his fellow commissioner, said he has “respected the courts and kept [his] head down doing the job.” Now that he’s facing voters for the first time, he told Bolts, “My focus is listening, explaining complex decisions in plain English, and earning trust community by community.”

In November, Echols faces Democrat Alicia Johnson, a community development advocate and health care administrator, who didn’t reply to Bolts’ interview request. The winner will serve a five-year term ending in 2030.

Fitz Johnson faces Democrat Peter Hubbard, a clean energy advocate who has worked in solar energy development. HB 1312 provided that the winner of this race would serve just a one-year term, before facing voters again in 2026 for a full term.

Hubbard says he entered the race even knowing he’d only serve a one-year term due to the new election rules.

“Calling the Republican bluff of overcoming their many voting barriers has affected my race by providing impetus,” he told Bolts in an email.

Over the course of their extended tenures, the commissioners made a number of consequential decisions that’ll affect Georgia’s energy supply and carbon emissions well into the future. They approved a plan for Georgia Power, the utility that generates and supplies electricity for more than 2.8 million residents and businesses across the state, to expand its capacity by constructing new natural gas turbines and buying energy from a coal-powered plant in Mississippi.

More recently, the commission has also approved several new renewable solar energy projects for Georgia Power, though at a rate that even some commissioners have judged insufficient.

Of most immediate consequence for voters, the PSC approved six requests by Georgia Power to increase electricity rates paid by customers between 2023 and early 2025. Commissioners cited as reasons for this increased fuel and electricity costs due to broader inflation.

“No one ever wants prices to rise—not for eggs, toilet paper, cars, bus fares, Netflix, clothes rent or energy,” Echols told Bolts. “Everything went up in our society and power bills could not avoid taking the hit.”

But the hikes have also helped pay for the construction of two new nuclear power generators at Plant Vogtle, a massive project plagued by long delays and a ballooning budget.

The rise in prices approved by the PSC has sparked public pushback and anger. At the start of 2025, the average household was paying $516 more in annual electricity bills compared to two years prior. The commission instituted a rate freeze in July of this year, though rates may still go up next year to pay for storm damage from Hurricane Helene in 2024.

“The messaging coming from PSC, and from the power company as well, is one of residents having to make sacrifices—they should be unplugging their utilities, they should be using less power—rather than one that sees these customers with an eye of humanity, and one that hears what the customers are actually feeling,” di Cicco told Bolts.

Hubbard, one of Democratic candidates, told Bolts that commissioners are currently too deferential to Georgia Power, saying they merely “rubber stamp” the power plans the company puts forward. He says that, if he’s elected, his top priority would be to lower power bills for residential customers. Alicia Johnon, the other Democratic challenger, has said she’d oppose “unchecked rate hikes.”

Hubbard and Johnson are also both running on ramping up clean energy production. Hubbard has published independent models of Georgia Power’s energy plans. He told Bolts, “Without fail, the lowest-cost model solution selected renewable energy, not fossil fuels.”

The at-large setup of PSC elections coincided with another quirk of Georgia election rules that made it harder for advocates to mobilize Georgians around climate and energy issues: mandatory runoffs, which create situations like the eight-person turnout in Miller County.

All Georgia voters can choose to participate in either major party’s primary, but the June primary elections where the PSC commissioners were on the ballot saw a staggeringly low turnout of 2.8 percent statewide. Hubbard and his primary opponent Keisha Sean Waites failed to clear 50 percent of the vote that day, and had to face off in a head-to-head showdown in July, when turnout dropped even lower: Just 1.5 percent of registered voters decided the runoff between Hubbard and Waites. Hubbard won with just 66,140 votes, in a state with more than 7 million registered voters.

Turnout was so low as to make some local administrators question the merits of even holding the election.

“I always try to be careful when I talk about the costs associated with elections, because on the one hand, we’re talking about somebody’s rights, and it’s hard to put a price tag on that,” said Joseph Kirk, the election supervisor of Bartow County in northwestern Georgia. “But at the same time, we have to be fiscally responsible with taxpayer money. And if we know the [turnout’s] gonna be small, we need to take steps to save some money in the general fund as a result.”

His county saw a 1.3 percent turnout for the first round of the primaries, and less than one percent for the runoff. “That’s 285 voters out of 84,000,” Kirk told Bolts.

Calhoun also felt the pressure of organizing a runoff. “I use all retired people to help as poll workers, and I worry about overloading them,” he said.

It’s why the Georgia Association of Voter Registration and Election Officials, where Kirk serves as president, threw its support behind a 2023 piece of legislation to lower the threshold needed to avoid a runoff from 50 percent to 45 percent. Democrat Saira Draper, the state representative who sponsored the bill, told local media at the time, “We have too many elections here in Georgia.”

The bill would have only applied to general elections, not primaries. Still, a Bolts review found that it’d have been enough to eliminate the need for five of the 15 statewide runoffs Georgia has held over the last decade.

Scholars trace the origins of Georgia’s mandatory runoff rule back to Jim Crow-era tactics aimed at blunting the power of Black voters and consolidating the white vote. Originally, Georgia had a “county unit” system that it applied to statewide primaries, akin to the Electoral College in national races, that delivered all of a county’s unit votes to the winner of the popular vote. When that was struck down as unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court, legislators in the early 1960s adopted a majority-vote requirement for primary races.

In his 2020 article for the Georgia Law Review, Graham P. Goldberg, an Atlanta attorney, notes that there were “good governance” arguments to be made for this policy—warding against other election manipulation tactics, and ensuring that a winning candidate really had the support of the majority of the people. But, Goldberg says, there were also racially discriminatory motivations; to consolidate the power of rural white voters and block Black-supported candidates from winning.

One legislator said in 1963 as a bill requiring runoffs was advancing in the legislature: “I do not think that statewide majority vote requirement would have been passed had [House] members not been convinced of the racially discriminatory potential of the runoff system.”

Georgia’s runoff system has been challenged multiple times in court, but today has remained intact. Draper’s 2023 runoff reform bill died in committee, and no successor bill appears to have been introduced since.

If evidence from the first round of voting is to be believed, this year’s general elections for the PSC are likely to fly under the radar once again. But climate advocates are hoping they can focus attention on them.

They point to a “perfect storm” of the new election schedule coinciding with a record-hot summer of heavy energy use and high electricity rates—plus public outcry over the arrival of new large-scale, energy-intensive data centers of processors built to support emerging technologies like AI that are expected to increase the state’s energy demands into the future.

“You see local counties pushing back, because they’re hearing from their constituents, ‘Wait, what does this mean for our air quality? What does this mean for water demands? What does this mean for power?’” said Marqus Cole, organizing director for Georgia Interfaith Power and Light, a faith-based climate advocacy organization.

“They’re hearing about data centers, and then on the back half of the year, here’s a chance to vote for two of the five people that were a part of that process. It’s really an important thing that people are hearing about, and they’re putting those dots together.”

Johnson defended his support of the data centers, saying, “Growth is welcome with guardrails.” He said he’s worked to prevent the burden of data centers from falling on customers.

The November election for Johnson’s District 3, which is the district that includes Atlanta and surrounding areas, will be the first test of Georgia’s odd combination—district representation and at-large voting—since it was challenged in the lawsuit five years ago. Fitz Johnson, the Republican nominee, is Black, and as a gubernatorial appointee he has never had to court voters. Hubbard, who is white, is the Democrat endorsed by most liberal-leaning groups.

The last time Georgia held an election for this seat, in late 2018, Democrat Lindy Miller handily won the counties in District 3 whose interest this commissioner is meant to represent. But she lost the election to Republican Chuck Eaton by 4 percentage points statewide.

What’s more, that election was decided in a December general election runoff, where turnout collapsed by more than half compared to the total number of votes cast in November. It could have fallen even more, but a higher-profile runoff for secretary of state also drew voters.

This year, there’s no other statewide race than the PSC elections to bring Georgians to the polls. But turnout may be helped by the fact that there will be municipal elections on the ballot in some places, including the mayoral race in Atlanta, where Andre Dickens is running for reelection. Hubbard, like all Democrats, will need very heavy support in the Atlanta region.

Kirk, the Bartow County election supervisor, thinks that the commission’s unusual structure may have disincentivized some of his county’s voters from participating in the July runoff for the District 3 seat, which lies hundreds of miles away. “Some of the more savvy voters, who understood where the districts were, chose not to vote in that election,” he told Bolts. “They just didn’t see it be worth their time to come in to vote for someone who didn’t represent them.”

This story was produced as part of the Democracy Day journalism collaborative, a nationwide effort on Sept. 15, the International Day of Democracy.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.