Long Lines, Short Windows: How Georgia’s New Restrictive Voting Law Complicates the Senate Runoff

In the first runoff election since Georgia Republicans passed a sweeping 2021 law restricting ballot access, voters are facing hurdles to early voting and absentee ballots.

Anoa Changa | December 5, 2022

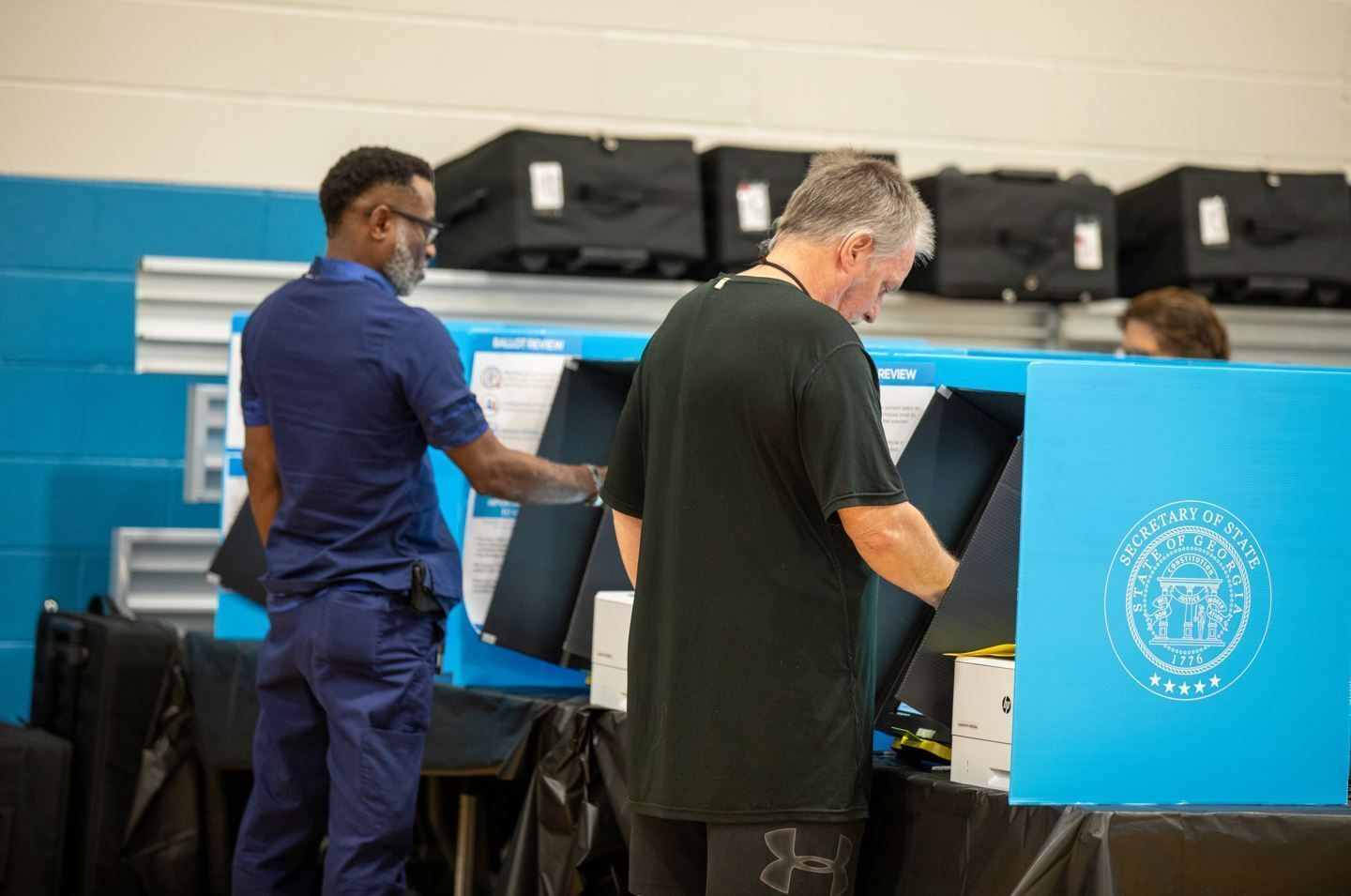

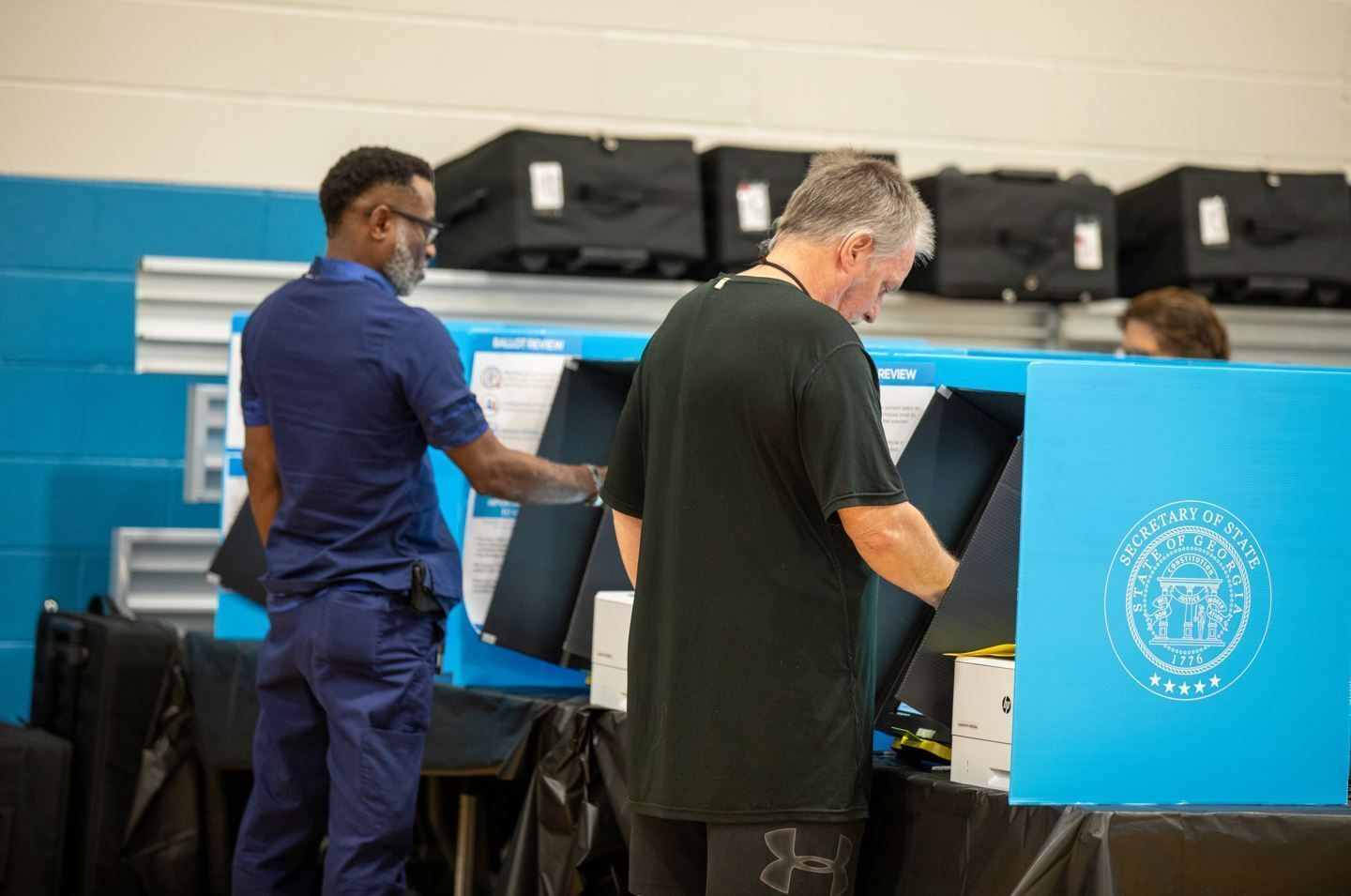

With voting underway in the 2022 Georgia Senate runoff, voters have taken to the polls en masse, but are having to overcome significant logistical hurdles to make their voices heard at the ballot box.

From the very first days of early voting, voters queued in long lines all around the state waiting to cast their ballots in person. Some polling sites in the Atlanta metro area had estimated wait times of two to three hours.

A handful of counties offered Saturday voting on Nov. 26 after Thanksgiving, despite objections from the state’s Republican leadership, such as Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger. The majority of the state opened the polls on Monday Nov. 28, which saw a record 300,000 people turn out. According to the secretary of state’s website, more than 1.7 million votes have been cast in early voting so far.

Speaking with Bolts, Crystal Greer from Protect the Vote GA, a grassroots group formed to combat voter suppression, said the current scramble to turn out voters was exactly what voting advocates worried about after the passage of Senate Bill 202 shortly after the 2020 election and Senate runoff.

“We knew that what we’re seeing right now is what that bill was pretty much created to do,” Greer said. “The lines you’re seeing right now are not a good sign. A form of voter suppression.”

Just as they did two years before, Georgians are turning out to decide an open Senate seat in a runoff election after no clear winner emerged in the contest between Republican Herschel Walker and Democrat Raphael Warnock, the incumbent Senator. Control of the Senate is not at stake this time, but Democrats are looking to expand their majority.

But unlike the 2020 election, where the runoff period lasted nearly two months, this cycle there’s approximately four weeks with only five days of mandated early voting. Republicans tightened the runoff election period with a provision in SB 202 last year, a move that advocates at the time worried would make voter turnout more difficult.

The bill, signed into law by Governor Brian Kemp in 2021 with support from Raffensperger and other Georgia Republicans, created myriad new obstacles for people who want to take part in the runoff. It has meant, for one, that people could not register to vote after Nov. 8 because there isn’t enough time for them to get on the voter rolls, unlike in the run-up to the 2021 runoffs.

It also shortens the window to vote by mail, a procedure that Democrats have rushed toward since the pandemic; voters had less time to request a mail-in ballot (that deadline was Nov. 25) and must mail it back by the deadline of runoff Election Day. It also limited the use of secure absentee ballot drop boxes to only during the early voting period. Ballot drop-off was further restricted to the times early voting polling stations are open, versus 24-hour availability in 2020.

That change has added pressure on the state’s in-person voting facilities, as already short-staffed polling places have had to simultaneously certify the results of the general election and prepare for the runoff election. Capacity has been a factor in the serpentine lines voters have had to contend with.

Most contentiously, the shorter window threatened the viability of weekend voting. Raffensperger’s office originally interpreted the law to prohibit early voting on Saturday, Nov. 26, due to an existing law saying that voting cannot be held immediately following a state holiday. A lawsuit filed before Thanksgiving challenged Raffensperger’s determination, leading upwards of 22 out of 159 counties to open locations for Saturday voting.

All of these restrictions have impacted students home for the holidays and full-time workers unable to wait in line during the week, for whom the importance of weekend voting—along with these other alternative methods of voting—cannot be stressed nearly enough.

During a press briefing, Vasu Abhiraman, senior policy counsel at the ACLU of Georgia, spoke about the challenges the tight timeline and confusion around Saturday voting caused for many voters, including students.

“We had short lines on Election Day two years ago, for both the general election and the runoff, because there were robust early voting opportunities and opportunities to vote by mail,” Abhiraman said. “What do we see here for the runoff? Well, we see absentee by mail, nearly an impossible proposition. We have been contacted by so many out-of-state students who are worried about voting absentee by mail.”

Abhiraman said he waited an hour and 45 minutes to vote at a library in DeKalb County in metro Atlanta.

Besides the confluence of issues during this runoff that stems from SB 202, Raffensperger’s actions as secretary of state have fueled challenges. Raffensperger gained national attention for opposing then-President Donald Trump’s subversion effort in 2020, but he then channeled that reputation to defend the GOP’s changes to voting laws.

“The cries of ‘voter suppression’ from those on the left ring as hollow as the continuously debunked claims of ‘mass voter fraud’ in Georgia’s 2020 election,” he said in 2021.

But Raffensperger has a history of fanning the flames of suspicions about election integrity; in the 2020 primary he created a criminal task force to investigate alleged absentee ballot fraud after mailing all eligible Georgia voters an absentee ballot application. (Nearly two years later, the group’s investigation found virtually no fraud.) After the general election, Raffensperger created a process with the Georgia Bureau of Investigation to conduct a signature audit of absentee ballots in Cobb County, something he previously had indicated was not possible.

In the run-up to the runoff, he issued guidance claiming the provision of Saturday voting after a holiday ahead of the Dec. 6 runoff was prohibited by a state statute, even though he had not challenged Saturday voting after a holiday ahead of the Jan. 5, 2021, runoff. Even after Saturday voting was allowed to proceed, Raffensperger’s office signaled to the state legislature it should address “the confusion.” That could result in an outright ban on Saturday voting in future runoffs. Georgia Republicans retained control of the state government on Nov. 8, so they have the ability to further restrict voting laws in their next legislative session.

Meanwhile, students like Madeline Berns are already experiencing challenges trying to vote. Berns told Bolts that she lives an hour south of where she currently attends school. Planning to vote in the 2022 general election, Berns said she applied for an absentee ballot on Sept. 23. She said the ballot was issued on Oct. 11 but never received it.

“On Election Day, I had to skip school and leave a medical appointment early to vote at my assigned polling place,” Berns said. “It took about three hours out of my day and 80 miles worth of gas. The poll workers hadn’t filed a provisional ballot before, so they were confused. We got it worked out, though.”

Reflecting on the 2020 election, Berns said she voted absentee without issue. With the tight turnaround for the runoff election, she planned to drive home on Election Day.

“I don’t want to risk that again, so I didn’t apply for another absentee ballot,” she said. “My county didn’t have early voting when I was home for Thanksgiving. It’s unfortunate because I’ll be in the middle of finals season, but I think it’s important.”

Voting rights advocates and engagement organizers say the secretary of state should have done more to ensure voters had the best information available about polling locations and voting options. County election boards, which in the 2020 election took advantage of donations from voting-focused non-profit organizations such as the Center for Tech and Civic Life to fund election administration, were banned from directly receiving such funding under SB 202. The secretary of state’s office has the power to step up its assistance, but so far has not, leaving non-profit organizations to stand in the gap.

During a press briefing at the start of early voting, Stephanie Ali, policy director at the New Georgia Project, said the coalition reached out to officials in each of the state’s 159 counties to get the correct information out to voters. According to Ali, the secretary of state’s site had little to no information going into the weekend early voting.

“We did the legwork,” said Ali. “This is work that shouldn’t have to be done by nonprofit organizations. It shouldn’t have to be done by political entities. It should be done by our counties, especially our Secretary of State.”

Greer said that some polling locations around the state needed more workers on site, resulting in long lines during early voting. She attributed the poll worker shortage partly to the increased attacks on poll workers in the aftermath of the 2020 election.

“You have this bottleneck happening in these lines because there’s only two people working or something like that,” she said. “There’s no incentive to hire new poll workers. And also make them feel safe.”

The various accounts of workers being doxxed, harassed and threatened created a chilling effect for some who might otherwise sign up. Greer also said proper training was an issue.

“We’re still evolving with these voting machines, and so if something goes down, there’s just not enough adequate training for that person to reboot it,” she said. “The line literally stops. Nothing’s happening until that gets fixed.”

Greer said the voter protection coalition would continue fighting for improvements in election administration and expanding ballot access. Georgia voters have remained resilient and continued to vote regardless of wait times and tight deadlines, right up through the final hours of early voting.

Berns believes schools could do more to help students engage in the electoral process, like having Election Day as a school holiday.

“I don’t even think it’s an excused absence here,” she said. “It would be better, though, to just make sure absentee ballots are approved, sent, and received in a timely fashion.”

Joanna Louis-Ugbo, a student at Emory University and organizer with the Georgia Youth Justice Coalition, echoed the importance of making voting accessible for students.

“We had to fight to keep our precinct on campus because a lot of these students do not have cars or transportation to go to a precinct that will be a little bit further out,” Louis-Ugbo said. “It’s very important to have precincts on these campuses.”