Your Guide to the 2019 Elections, in Six Questions

Will 2019 grow the ranks of decarceral officials? The results will shape bail reform, policing and charging practices, ICE cooperation, voting rights, and more.

Daniel Nichanian | October 31, 2019

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

Will 2019 grow the ranks of decarceral officials? Next week’s results will shape bail reform, ICE cooperation, policing and charging practices, voting rights, and more.

The 2019 elections, which come to a head in Tuesday’s general elections, have brought a newly nationalized sensibility to local races for prosecutor, a year after immigrants’ rights activism did the same for sheriffs.

Incumbent district attorneys and DA hopefuls have used these elections to look beyond their jurisdictions and forge broader decarceral coalitions. They are chipping away at the longtime truism that prosecutorial alliances are among the staunchest foes of criminal justice reform.

Two of the country’s most emblematic reform-minded DAs, Philadelphia’s Larry Krasner and Boston’s Rachael Rollins, have jumped into campaigns far from home this year in a bid to elect like-minded prosecutors. Both endorsed Tiffany Cabán, a public defender who fell just short in June in the Queens Democratic primary. Both have already met with Parisa Dehghani-Tafti, a former public defender who won a June primary in Arlington, Virginia and is unopposed in next week’s general election. And both, alongside Chicago’s chief prosecutor Kim Foxx, now back Chesa Boudin, a public defender who is running to be DA of San Francisco.

Some local candidates in Virginia, meanwhile, have cast themselves as part of a broad effort to reshape statewide practices. Dehghani-Tafti told me she hopes to be elected “with a wave of other reform prosecutors” to “transform” Virginia politics, a sentiment Steve Descano (in Fairfax) and Jim Hingeley (in Albemarle) echoed. Reform-minded candidates are running as well in Chesterfield and Loudoun counties; and some fault Virginia’s existing prosecutorial association for being a “very regressive force,” as Hingeley put it. Similarly, in some New York counties like Ulster, candidates blame their state’s DA association for fighting reform. And in Pennsylvania, within which Krasner has been largely isolated so far, a public defender is running in Allegheny County (Pittsburgh) to “join forces” with Krasner.

The scale of new statewide and nationwide alliances is the first core question to be decided in Tuesday’s general elections. (Louisiana votes on Nov. 16.) Will they add to the ranks of decarceral officials, and if so will enough be concentrated in one state to change its politics?

Virginia may have the most potential to change the game if it scales up the sort of county-level reform seen in recent years to a statewide plane.

Reform-minded prosecutors may also gain allies in other types of officials. Virginia’s legislative races could expand the horizon of viable change just as the politics of prosecution are shifting. In Pennsylvania, Krasner is certain to gain is at least one in-state ally: Rochelle Bilal ousted the Philadelphia sheriff in the May Democratic primary with Krasner’s informal support. Bilal, who is unopposed in the general election, said then that she would would be a “partner” of the “reform effort which is presently active in Philadelphia,” alluding to Krasner’s policies.

Some local races are even drawing presidential candidates. U.S. Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren both backed Cabán in the spring; Sanders also endorsed Boudin this week. One of Boudin’s opponents, Suzy Loftus, has the support of another candidate, U.S. Senator Kamala Harris, whom she used to worked for. Loftus became the city’s interim DA this month when Mayor London Breed appointed her to fill a vacancy; some local groups protested Breed’s decision to bestow incumbency on one of the candidates weeks before Election Day.

Local elections should get more attention still from federal politicians who are fond of talking about reform. After all, criminal justice and law enforcement practices are largely shaped by state and local officials. Discovery and bail, voting rights, ICE cooperation, policing practices, charging and sentencing reform, health care access—all are directly on the line in November’s elections.

—

Voting rights hang in the balance. Where will Tuesday tip?

In each states this article mentions, the people most directly affected by the criminal legal system are barred from voting on Tuesday. These states disenfranchise people who are in prison for felony convictions; most also disenfranchise people on probation or parole, and in a few, these bans are permanent. The rate of exclusion is uniformly higher among African Americans, who are subject to heavier policing and prosecution, with a record 26 percent barred in Kentucky.

In Mississippi, for instance, where many formerly incarcerated people face health issues but do not qualify for Medicaid under current rules, most cannot weigh in on a governor’s race shaped by debates over the Medicaid expansion.

The future of voting rights hangs in the balance in Kentucky and Virginia, two states whose laws provide for lifetime bans, as I wrote in September. Virginia, where Democrats are trying to win control of the government, could eliminate lifetime disenfranchisement, if not guarantee voting rights for all citizens. In Kentucky, Attorney General Andy Beshear, a Democrat, is running for governor on a pledge of issuing an executive order to restore voting rights to Kentuckians “who completed their sentences after being convicted of a nonviolent felony.” This could enfranchise about 140,000 people. Matt Bevin, the Republican incumbent, rescinded just such an order when he entered office in 2015.

This issue even shapes prosecutorial races. Hingeley, the Virginia candidate, told me he would be mindful of the loss of voting rights when deciding whether to charge an offense as a felony. Hingeley, a Democrat, is challenging Albemarle County’s Republican prosecutor Robert Tracci, who joined a brief in support of a 2016 lawsuit to block an executive order restoring the voting rights of people who have completed their sentences. Two other prosecutors who supported that lawsuit were already ousted in the Democratic primaries in June.

This fall also marks the first election in which people enfranchised by Colorado and Louisiana’s brand new laws expanding voter eligibility will get to participate.

—

Will Tuesday’s elections ease the way for pretrial reform?

New York limited cash bail and mandated that prosecutors quickly disclose evidence. But state DAs are now responsible for carrying out those changes, and evidence has surfaced this week that some are undermining implementation. City & State NY reported that an assistant Nassau County DA gave presentations on how to circumvent these reforms. This captures the difference it can make whether a DA supports or opposes their goals. But in Nassau County itself, the incumbent DA, a Democrat who has pushed for punitive change to state law, is facing a Republican challenger who is even more openly critical of the state’s new reforms.

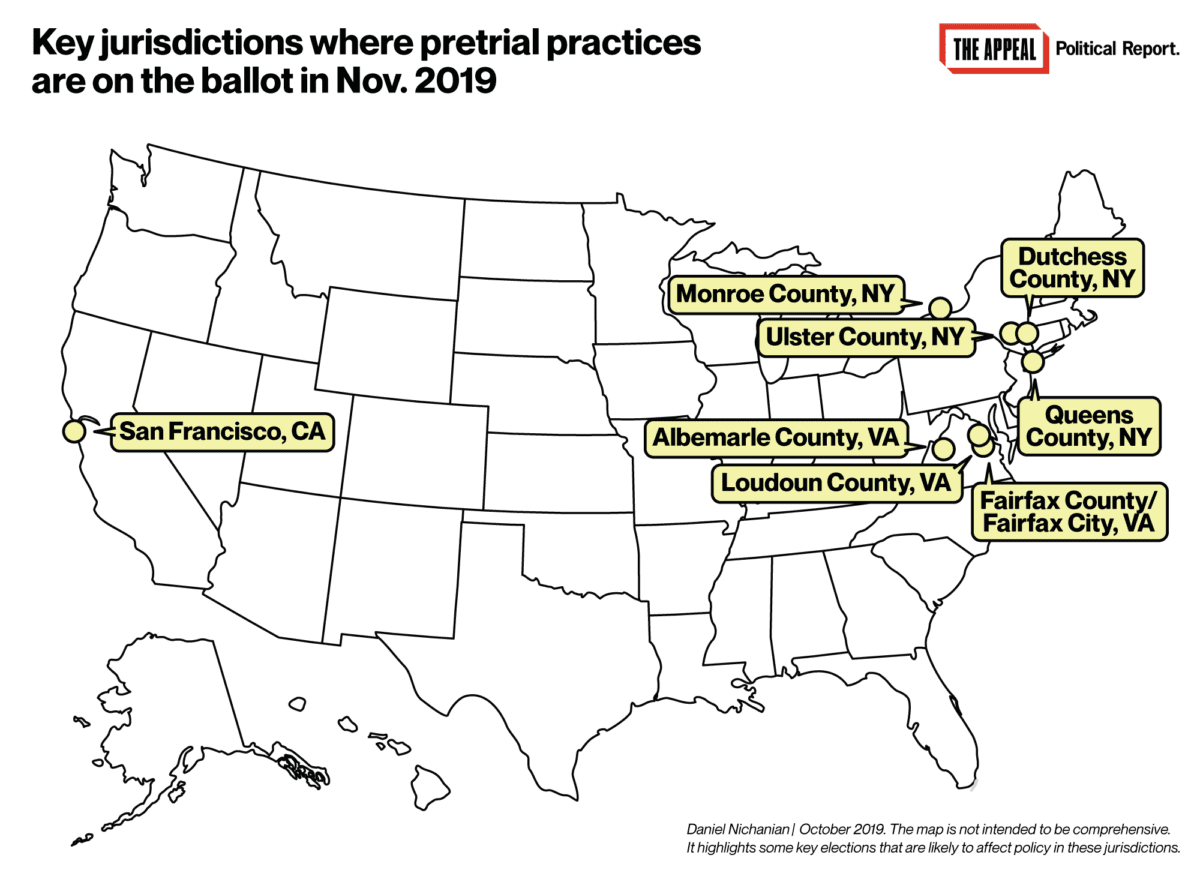

Elsewhere in the state, though, DA races feature significant contrasts on pretrial practices, as I reported in October. In Queens and three upstate counties (Dutchess, Monroe, and Ulster), critics and defenders of the pretrial reforms are facing off.

Monroe (Rochester), the largest of the upstate counties, features a clash between DA Sandra Doorley and Shani Curry Mitchell. Doorley, a Republican, has played a leading role in raising concerns about the reforms as president-elect of the state’s DA association. Mitchell, a Democrat, faults Doorley’s “scare tactics.” In Queens, borough president Melinda Katz, who prevailed against Cabán, committed during the primary to end cash bail and institute open-file discovery; she faces Republican Joe Murray, who opposes both the pretrial reforms.

Discovery rules also loom large in Virginia, where prosecutors face lax requirements to share information, a system critics have called “trial by ambush.” Some reform-minded candidate want to strengthen their jurisdictions’ policies. “We shouldn’t be using the power of information and failure to provide as a means to convict somebody because we think that they should be found guilty,” said Buta Biberaj, the Democratic nominee in Loudoun County.

Virginia may also tackle bail reform. Hingeley said he would never seek cash bail in Albemarle; the Prince William County candidates disagree on the issue; and Descano warns in addition about the possible racial biases of using algorithmic tools to determine pretrial detention. And the issue has played out in San Francisco as well. Boudin touts the initial role he played steering a lawsuit against the city’s pretrial detention practices.

—

Will the 2019 elections reduce charging practices and the volume of prosecutions?

The 2018 cycle’s defining policy proposal was Rollins’s pledge to decline to prosecute a range of low-level offenses. Cabán followed suit this year in promising to decriminalize sex work. Still, most candidates have largely stayed away from declination commitments this year, at least on matters other than marijuana possession (which Dehghani-Tafti, Descano, and Middleman say they would decline).

They have tended to focus on reducing the number of convictions through new pretrial diversion programs, as Scott Miles, the commonwealth’s attorney of Chesterfield County, Virginia, has done to criticism from his general election opponent. In such programs, which are typically targeted at lower-level cases, prosecutors file charges but agree to drop them if the defendant completes a series of steps, such as receiving treatment. Descano and Biberaj, among others, are now running on implementing such policies to ensure that more people do “not have that record that follows them around,” as Descano put it. In San Francisco, however, Loftus pushed back against this diversionary strategy on Wednesday, two weeks after becoming interim DA; she killed a diversion program meant to dismiss first-time DUI charges if the defendant undergoes behavioral therapy.

Some candidates also want to reduce the number of felony-level convictions by prosecuting more cases as misdemeanors. Misdemeanor charges trigger less severe, though still considerable, penalties; Hingeley says this approach would “make it more likely that a person could stay in the community.”

Drug cases get the brunt of the attention when it comes to diversion. Yet the frequent admonitions to approach addiction as a public health issue have coincided with a surge in a punitive practice: Some prosecutors are increasingly treating overdoses as homicides, which often targets people who use drugs themselves. In reporting on this issue, I identified only one DA candidate who pledges to never seek drug-induced homicide charges: Hobie Crystle, a Democrat who is running in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. It just so happens that Lancaster has used this sort of charge more frequently than any other county nationwide, setting up the potential for a major policy shift. This issue also separates DA candidates in Allegheny (Pittsburgh) and Monroe (Rochester) counties, and Delaware County, Pennsylvania.

—

Policing often evades reform and accountability. Can voters bring it via the polls?

Allegheny County (Pittsburgh) votes in the shadow of Antwon Rose II, a Black teenager shot and killed by a police officer who was acquitted in March. A Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article subsequently documented a pattern of inadequate accountability under Stephen Zappala, the county’s longtime Democratic incumbent DA. Lisa Middleman, his independent challenger, says a DA should never have the final word on whether to prosecute a police officer.

Middleman has also committed to not relying on evidence or testimony provided by police officers with a history of misconduct, as have other candidates running this fall such as Descano in Fairfax County, Biberaj in Loudoun County, and Boudin in San Francisco. Local police unions have intervened against a number of them, including in Fairfax and San Francisco. Loftus, the interim DA of San Francisco, is the former head of the San Francisco Police Commission. She is running as a reformer and supports independent investigations into misconduct, The Appeal reported in October, but local advocates have questioned her record on police violence.

Jennifer Riley Collins, Mississippi Democrats’ attorney general nominee, emphasizes a need to change police behavior at the outset. She wishes to train officers to make fewer arrests so as to free up resources for community services. And sheriffs shape policing practices, too: Jorge Amselle, running for sheriff in Warren County, Virginia, told The Appeal that sheriffs can be at the forefront of policing reform given their vast policy discretion.

—

ICE has largely avoided detection in the 2019 elections so far. Will that change Tuesday?

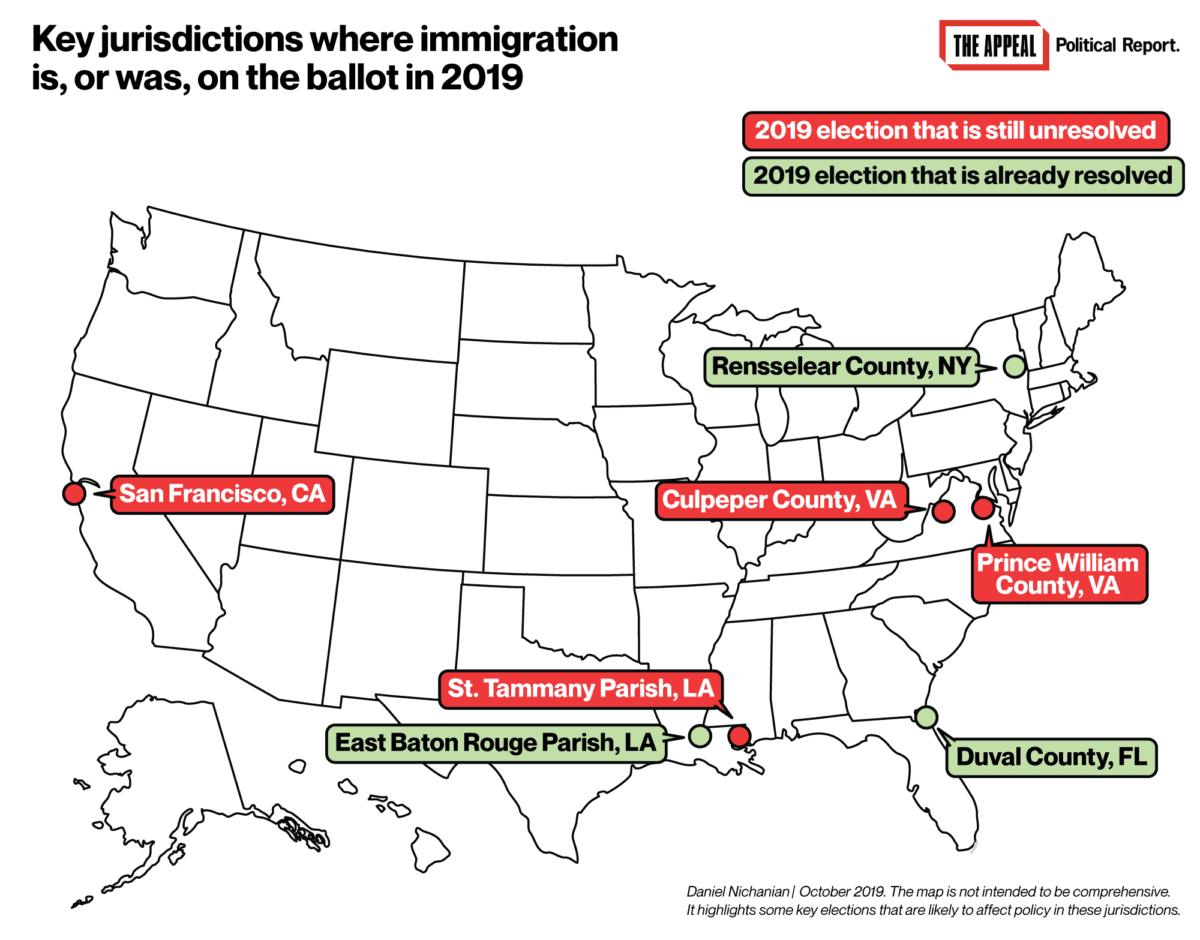

In 2018, longtime sheriffs abruptly lost in elections defined by their cooperation with ICE. That template did not carry over to 2019, though, a mix of absent competition and Democratic Party inattention or indifference.

The only New York sheriff who has joined ICE’s prized 287(g) program, which authorizes local law enforcement to act as federal immigration agents within a county jail, is running unopposed next week; he is a Republican sitting in a swing county. In Florida, a GOP sheriff who joined 287(g) drew a Democratic challenger who did not support leaving the program. In Louisiana’s largest parish, Democratic challengers pledged to quit 287(g) only to have prominent Democratic officials endorse the GOP incumbent, who easily won on Oct. 12. Many other Louisiana sheriffs with ICE contracts also won that day.

That leaves Prince William County, Virginia, as the main sheriff’s race where ICE cooperation is on the ballot on Tuesday.

In this populous Northern Virginia county, the 287(g) program has led thousands to be deported since 2007 in this county, and has been fought by immigrants’ rights advocates, I wrote in June. Josh King, a Democrat, is challenging GOP Sheriff Glenn Hill. He has said that terminating this agreement would be a priority. County rules are unusually complicated, though; to achieve that goal, King would need to win alongside 287(g) critics who are running for other offices.

Also in Virginia: The sheriff of Culpeper County, the state’s only other county with a 287(g) county, is up for re-election, and a candidate running for Loudoun County sheriff is pledging to minimize ties with ICE. Elsewhere still: New Jersey sheriffs friendly to ICE face challengers in campaigns that mostly did not take off; and the sheriff of Louisiana’s St. Tammany Parish was forced into an all-GOP runoff with a challenger critical of a local ICE contract.

Sheriffs have no monopoly over immigration policy, far from it. Boudin has said he would create a unit in the San Francisco DA’s office to inform defendants of the immigration effects of plea offers, and help prosecutors avoid triggering deportation proceedings. Middleman also told me she would add staff to advise on such consequences in Pittsburgh. Louisiana, conversely, could end up with a more restrictive landscape after 2019; Eddie Rispone, the Republican candidate in the gubernatorial runoff, has touted his desire for tougher immigration policies.

—

This guide only scratches the surface of Tuesday’s elections.

In Mississippi’s Hinds County (Jackson), Jody Owens is the only DA candidate on the ballot. Owens, the former managing attorney of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s state office, won a competitive Democratic primary on a platform of fighting mass incarceration. He faces a series of allegations of sexual harassment, Kira Lerner reported in an exclusive Appeal investigation in October.

There are also questions regarding sentencing reforms, mental health resources, Medicaid access, the death penalty (multiple Virginia candidates have pledged to never seek it), and private contractors: DA candidate Jack Stollsteimer wants to deprivatize the Delaware County jail in Pennsylvania, and a local jail’s private health-care provider is at issue in Virginia.

No matter how those issues are now settled by those permitted to vote, the 2019 elections have already shifted the politics of mass incarceration.

Cabán came within 55 votes of the Queens Democratic nomination after committing to draw her policies from “community members that are directly impacted by them.” Other candidates are now showing one can mount a viable bid for prosecutor while, or by, confronting the realities of incarceration. Hingeley talks of incarceration as “family separation.” And Boudin tweeted this week, “Incarceration means putting a human being in a cage. … We need to stop normalizing our system of mass incarceration.” The new coalitions for decarceration signal that the system already looks anything but normal for a significant section of the public.