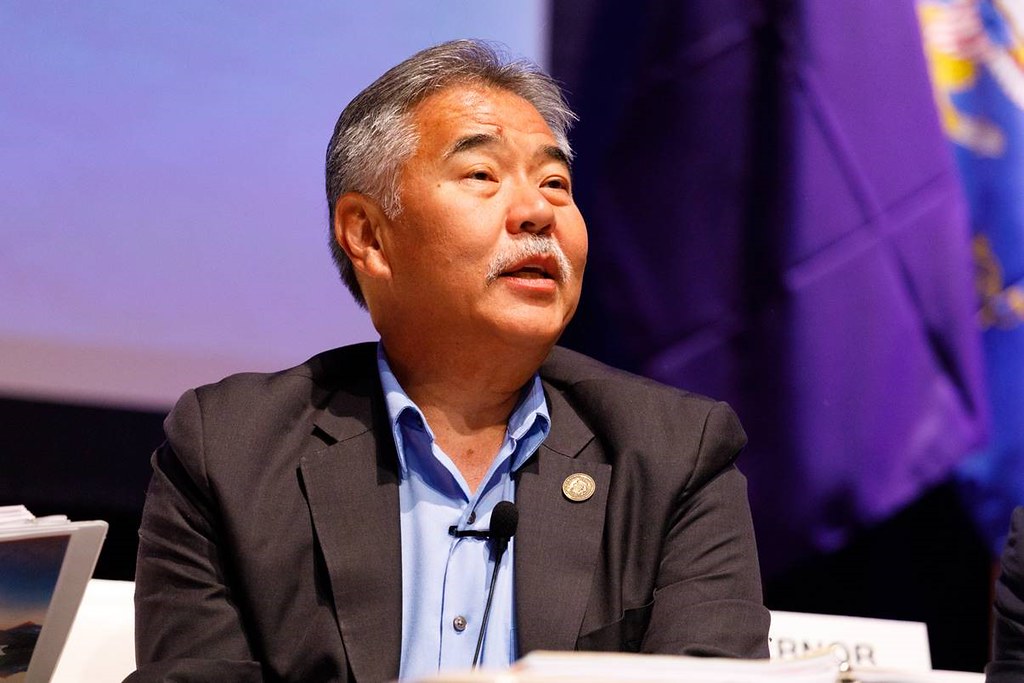

Hawaii Governor Sinks Criminal Justice Reforms, Allows Pot Decriminalization

Governor Ige vetoed bills restricting civil asset forfeiture and enabling the release of terminally ill people.

| July 18, 2019

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

Democratic Governor David Ige vetoed a series of bills reforming Hawaii’s criminal legal system last week. Among other proposals, he killed a measure to restrict the state’s embattled civil asset forfeiture programs and another for terminally ill incarcerated people to be eligible for medical release.

The legislature chose to not hold a veto override session, so the vetoes are final, disappointing criminal justice reform advocates.

“There’s longstanding deference to police and law enforcement in our state,” Mandy Fernandes, policy director of the ACLU of Hawaii, told the Political Report. “So any time we are trying to push across the finish line a bill that would reform policing or reform some of our criminal laws, it can be very difficult to do.”

Ige allowed a bill decriminalizing the possession of small amounts of marijuana to become law without his signature. The bill falls short of reforms other states have recently implemented.

To seize property, law enforcement still won’t need to file charges or obtain a conviction

In Hawaii, as in many states, police departments can seize a person’s property on the suspicion that it is connected to a crime, even if no one is ever charged or convicted. Proceeds go to law enforcement agencies and prosecutors.

House Bill 748 would have required a felony conviction before someone’s property could be seized. Arkansas adopted just such a law this spring. But Ige vetoed it last week. “This was a real heartbreaker as we have been talking to the legislature for many, many years about the injustice of seizing someone’s property without a conviction,“ said Kat Brady, the coordinator of the Community Alliance on Prisons, told the Political Report. She faulted Ige for listening “to law enforcement who are very protective of their slush fund.“ Ige’s office did not answer a request for additional comment on this bill, nor on the medical release one.

In a statement explaining his veto, Ige suggested that restricting civil asset forfeiture would encourage crime. He called it “an effective and critical law enforcement tool that prevents the economic benefits of committing a crime from outweighing consequential criminal penalties and punishment.” But for Fernandes, civil asset forfeiture is not commensurate with what it punishes. “When there were not even charges brought and property is taken, it’s clearly out of proportion with the alleged offense because there was no offense,” she said.

Ige also said during a press conference that he trusted law enforcement agencies to seize property appropriately. Hawaii County Prosecutor Mitch Roth echoed that sentiment, saying he “doesn’t know of a single case” in which the system has been abused.

At least one prosecutor disagrees. “I do think our state civil asset forfeiture process is in need of some serious structural reform,” Justin Kollar, the prosecuting attorney of Kauai County, told the Political Report. “That said, I wasn’t crazy about HB 748 for the simple reason that I don’t want prosecutors to have a financial incentive to achieve a conviction. If we decide that the idea of civil asset forfeiture is immoral then we should do away with it entirely.”

The state auditor’s office reviewed the forfeiture program in 2018 and found significant problems, including a lack of transparency and inadequate paths for people to contest a seizure.

Law enforcement actors say they have since fixed these issues, but Fernandes disputes that claim. “They are not requiring a criminal conviction, the clear profit incentive remains,” she said. Leaving it up to the agencies at fault to reform themselves also raises enforcement and oversight concerns.

Decriminalization survives, unlike other cannabis bills

Hawaii is decriminalizing the possession of small amounts of marijuana because of a bill that Ige allowed to become law without his signature. It removes the threat of jail for possessing under three grams.

That is the smallest amount among all 26 states that have decriminalized or legalized marijuana, according to the Marijuana Policy Project. Possessing less than three grams is still punishable with a fine. The law provides a procedure to expunge past convictions for marijuana offenses that are now decriminalized. But it only allows a past conviction to be cleared if it was accompanied by no other criminal charges. In addition, expungement would not be automatic, meaning that people will need to file a motion rather than the burden being on the state to clear their records. By contrast, Illinois recently adopted a procedure where individuals will not need to initiate the expungement process as long as their offense involved less than 30 grams of marijuana.

Still, the governor signaled that he came close to vetoing even this modest legislation, so bolder reforms may be a way off. Marijuana legalization failed in the legislature this spring.

And Ige outright vetoed other bills pertaining to cannabis, as he had last year. He killed one bill that would have enabled patients to carry medical cannabis between islands, and another that would have legalized the possession and sale of hemp.

Ige blocks compassionate release

House Bill 629 would have provided procedures by which incarcerated people suffering from a terminal or debilitating illness can request a medical release. During the legislative debates on this bill, Brady of the Community Alliance on Prisons reminded lawmakers that a substantial share of the state’s prison population is detained thousands of miles away, in Arizona. Medical problems compound the isolation from their communities. The legislation passed both legislative chambers unanimously. But Ige vetoed it.

He said in a statement that the bill is unnecessary because medical release opportunities already exist. Keith Kaneshiro, the Honolulu County prosecutor, opposed it on similar grounds. He said it duplicated policies implemented by the Department of Public Safety, which runs prisons in Hawaii. But the department supported HB 629.

This tactic mirrors the one on civil asset forfeiture: Ige and the prosecutors who urged vetoes say they favor certain policies while fighting their codification into law.

“It can be difficult to get agencies to follow the law,” said Fernandes. “But it’s much more difficult if we’re just trying to get them to follow their own policies and procedures that they can change at their own discretion. There’s something very valuable in codifying these civil rights reforms in statute.” Fernandes also disputes that the bills were merely duplicating existing policy.

Kollar, the Kauai prosecutor, echoed Fernandes. “Codifying an existing procedure that is working seems to be a no-brainer to me,” he told the Political Report. “Hopefully the legislature will take a fresh look at this one next session.”