How Pregnancy is Policed: Your Questions Answered

An expert on the criminalization of pregnancy responds to questions from Bolts readers on its long history, landmark cases, and new surveillance realities since Dobbs.

| August 15, 2024

Since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade two years ago, the legal risks that come from merely being pregnant have shot up in the United States.

Alongside the new bans on abortion, laws have popped up to encourage people to snitch on their neighbors and empower prosecutors to file criminal charges. So-called personhood laws are exposing more people to heightened punishment, plus endangering access to other procedures like IVF. The Republican Party has proposed scaling that up further by codifying ‘personhood’ at the federal level.

But pregnancy was policed long before the Dobbs decision came down. Even under Roe, many women faced arrest and prosecution due to allegations over how they handled their pregnancy.

Grace Howard meticulously lays out this history in her new book The Pregnancy Police: Conceiving Crime, Arresting Personhood. An associate professor of justice studies at San José State University, Howard has studied over 1,000 pregnancy-related arrests since 1973, a period that saw the rapid growth of the war on drugs. Her book reconstructs how legal statutes and surveillance tools were used to punish not just abortions, but also stillbirths and miscarriages.

As part of our “Ask Bolts” series, we invited you to ask Howard any question you had about the policing of pregnancy. And once again, you delivered with many thoughtful questions, touching on everything from landmark court cases to new technology. We narrowed your submissions to just nine reader questions to share with Howard, also throwing in a tenth from our own staff.

Howard replies to your questions below, sharing what gravely worries her about the realities of policing and surveillance today, but also finding advocacy to be hopeful about. We’ve organized your questions under four themes—explore at your leisure:

The realities of criminalization today

Read on to learn more about the most consequential legal cases, new tools of surveillance, and a lot more.

Decades of policing

Dobbs galvanized more attention on reproductive rights, but you began your research on the policing of pregnancy long before that decision. What was happening in the decades that your book covers—what has criminalization looked like, besides restrictions on abortion? And what made you start paying such close attention to it? — Bolts staff

In the decades before Dobbs, there was a lot of action in the courts and in state legislatures carving out fetal personhood beyond the scope of abortion. Fertilized eggs, embryos, and fetuses were defined as legal persons in tort law. Pointing to the reality of homicidal violence against pregnant people, pregnancies were defined as crime victims, independent of the people gestating them.

After Roe, criminalization began in earnest in the 1980s, as the “War on Drugs” drove punitive approaches to social issues, and the anti-abortion movement became a more organized political force. Panic over crack cocaine led to a focus on impoverished Black women who tested positive for the drug while pregnant.

Most pregnancy criminalization cases involve a positive drug test, but other arrest cases involve self-harm, car accidents, self-managed abortion or miscarriage, failing to protect a fetus from third party violence, and even failure to take good care of themselves.

Though I had been very passionate about sexual and reproductive health issues, I actually didn’t realize that the criminalization of pregnancy was happening until grad school. We read Dorothy Roberts’ Killing the Black Body and I was forever changed. I was outraged—that it was happening, that so many people either didn’t know or didn’t care. And, there were some great law review articles on it, but not a lot of data. So, I decided I wanted to do something about that.

What are some landmark legal cases related to the criminalization of pregnancy that concerned citizens should be aware of, and what were their implications? — Chrissy T.

This issue has only come before the Supreme Court once, in Ferguson v. City of Charleston, a 2001 case. This case began as a lawsuit against the Medical University of South Carolina, which had adopted a policy of drug testing certain pregnant patients and reporting positive tests to law enforcement. By the time the case got to SCOTUS, it wasn’t about whether we could punish pregnant folks for crimes against their pregnancies, it was about illegal searches and seizures: Can you drug test a patient for the purposes of law enforcement activity alone, without reasonable suspicion or a warrant? The court said no, you can’t.

And yet this hasn’t stopped the practice: The case only ever applied to public medical facilities, and healthcare providers can essentially lie about why a drug test is offered.

Today, drug testing and reporting of pregnant patients and newborns is common and widespread, though most of the time the reports result in family court cases, not criminal ones.

Another notable case is ex parte Ankrom (2013), which is when the Alabama Supreme Court said that a 2006 law passed by Alabama to punish the chemical endangerment of a child could also be applied to pregnancy. Despite the law saying nothing about pregnancy, the court basically defined fertilized eggs as “children” and uteruses as contaminated “environments.” Though pregnancy-related arrests started years before Ankrom, the decision emboldened prosecutors and opened the door to further legal developments.

For example, the Alabama Supreme Court case earlier this year that defined embryos created by IVF as extrauterine children, endangering the procedure in the state, cited Ankrom multiple times as precedent.

What does your research show about the way women of color and low income women have been treated on this front during the period you studied, versus white women and higher income women? — Morgan M., from California

The criminalization of pregnancy is inherently racist. Across the U.S., the drugs that women of color are more likely to use have been treated with more scrutiny and have been uniquely stigmatized than those used by white women, despite comparable rates of substance abuse.

Alabama has been a somewhat different story, in that the racial composition of the arrest pool is much more comparable to state demographics—although this does not mean that it has a racially egalitarian criminal justice system. Alabama’s criminalization period started in 2006, when the big drug panic was related to home-cooked methamphetamine. This focus on meth, and the drug’s association with impoverished white people, led to a wave of them being targeted.

In my book, I explore rhetorical connections between the panic over so-called “meth babies,” to the early U.S. eugenics movement’s focus on impoverished white people—a white supremacist attempt to shore up the strength of the “white race” by eliminating the whites on the fringes. While information on income was not available in all of my cases, I was able to see if a defendant qualified for a public defender. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the vast majority of the people who were arrested in my study were impoverished enough to qualify for public defense.

The realities of criminalization today

When I was pregnant in MA in 2021, I was told that because I had a medical marijuana card prior to being pregnant, I could be drug tested at any point in my pregnancy, even though I reported not using it while pregnant. When I read up on the legality of that, I found out that women testing positive for marijuana during delivery accounted for the largest share of referrals to the Department of Children and Family Services. I would love to know more about how marijuana can be legal in a state but criminalized for pregnant people. — Mae, from Massachusetts

Unfortunately, there are a lot of areas of law where pregnancy knocks a person down a peg, legally. You can lose some of your most fundamental rights, including the right to reject medical treatment, the right to privacy, the right to liberty. And people who are reported to Child Protective Services for using drugs during pregnancy usually lose their children at least temporarily—an inherently traumatizing experience. This has included people who use legally prescribed medications, including marijuana.

A case on this question just came out of Oklahoma. The state’s Court of Criminal Appeals ruled that you cannot be prosecuted for using medical marijuana while pregnant; local prosecutors were trying to charge multiple women with criminal neglect. This does not, however, prevent CPS from getting involved—this would be left up to the discretion of the relevant agency.

I’m in Virginia, the last state in the South with access to abortion, and law enforcement here has advocated for a wide expansion of Automated License Plate Reader (ALPR) technology across the commonwealth. Attorneys general across the country have articulated their desire to access this sort of data to track movements of pregnant people to see if they access abortion care across state lines. What are some of the dangers of expansive surveillance networks, like Flock’s ALPR networks, and how does that apply to access to care? — Shawn W., from Virginia

Some of the key differences between today and the last time abortion was criminalized are that our criminal justice apparatus has expanded considerably, as have our surveillance networks.

All forms of electronic surveillance, from ALPR to credit card transactions can potentially be used as evidence in a pregnancy case. Law enforcement can get clearance to examine your text messages, your search history, your credit card statement, and even GPS data to track your location. I worry that this will frighten people away from using the internet to find safe ways of self-managing pregnancies, to arrange travel out of state, or even to find support in understanding what options and resources are available. This leaves people who need abortions isolated.

That being said, we haven’t found a single case where a person was “caught” because of their digital footprint. Everyone who has been arrested, to date, was found because a person told on them: a neighbor, a boyfriend, a nurse. We need to be cautious about who we talk to.

Is performing an abortion the only situation in which these laws apply criminal liability to men? — Alan M., from Washington

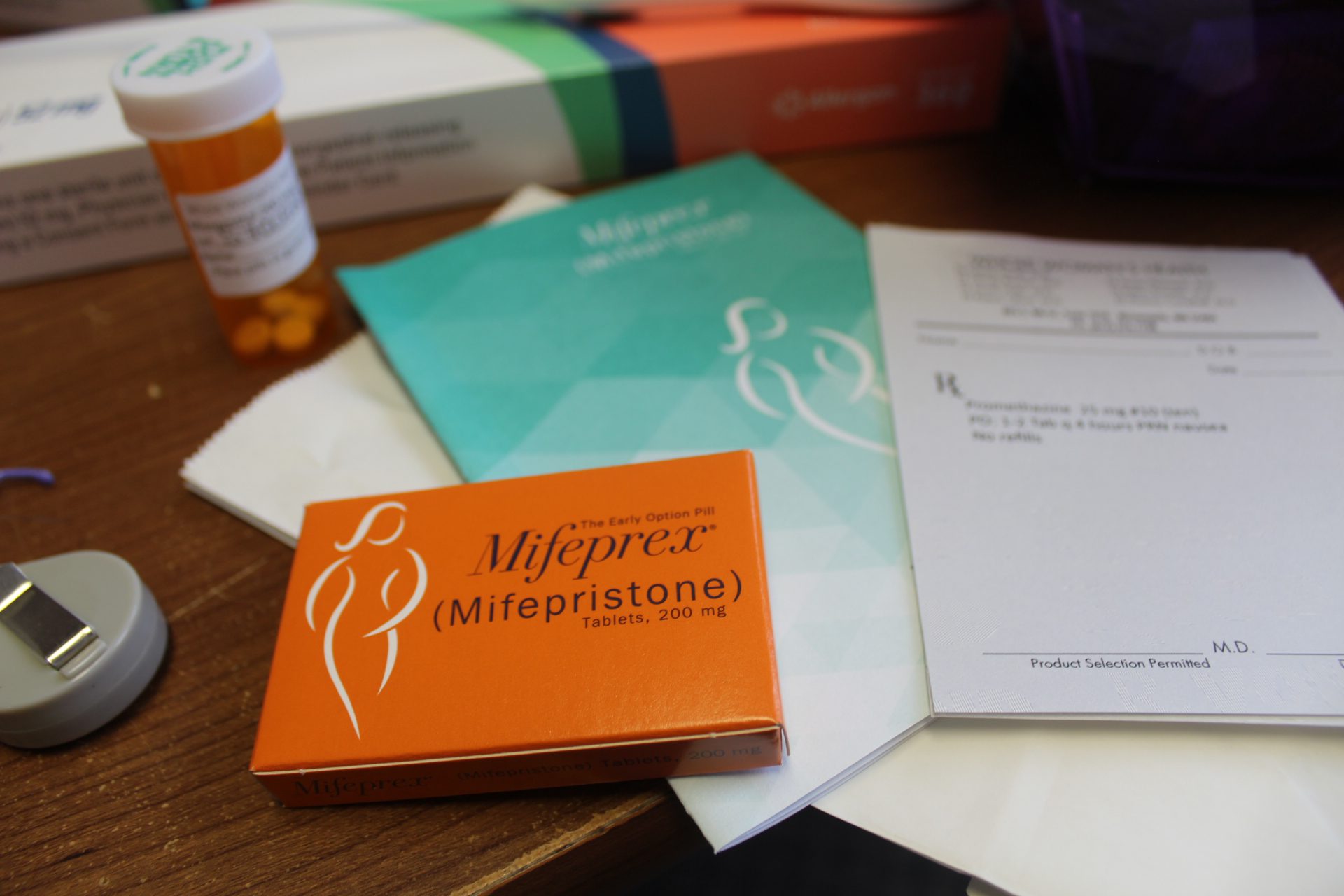

So far, yes, the only situation where cisgender men have faced prosecution is for performing abortions. But some states have also been exploring the criminalization of abortion “helpers.” A new Louisiana law goes into effect on October 1 that will classify abortion pills as “controlled dangerous substances.” Any non-pregnant person found to be in possession of these substances without a prescription has committed a crime–even if that person has secured the medication for their own future use in the event of an unplanned pregnancy.

Meanwhile, in family court, there have been a few cases where men have been targeted; not for using drugs themselves, but for failing to prevent their wives from using drugs. This is reminiscent of the law of coverture, a “olde time” legal doctrine from English common law, that basically treated women like legal dependents of whichever man they were attached to—a father or brother or husband. Men were held responsible for “making” their wives behave.

Standards of care

How do these laws affect women with ectopic pregnancies? My friend had an ectopic pregnancy after her daughter was born; the doctors recommended she have tubal ligation to ensure no additional similar pregnancies. — Kirsten, from Maryland

In case readers don’t know, an ectopic pregnancy is a pregnancy where the fertilized egg has implanted somewhere other than the uterus, most often in the fallopian tube. These pregnancies are never viable, and they are extremely dangerous, as the growing embryo can cause tissues to tear and organs to rupture. These must be treated by ending the pregnancy with surgery or with a medication called methotrexate.

Ectopic pregnancies have been in the news since the Dobbs case, because these medical emergencies bump up against vague laws banning abortions. Healthcare providers are put into a position where they have to wonder: Will offering this life-saving care result in the loss of my medical license, or even my incarceration? For example, in Texas, healthcare providers face 99 years in prison if a prosecutor decides they have violated the abortion ban. In practice this means that emergency medical care can be dangerously delayed while lawyers try to decide whether or not your doctor is allowed to help you.

This is what happened to Kelsie Norris-De La Cruz, a 25-year old woman in Texas who was ordered to go home and wait after she was diagnosed with an ectopic pregnancy, as there was a chance the pregnancy was still “alive.” She was unable to receive care until her fallopian tube began to rupture.

(Editor’s note: A new investigation published this week by the Associated Press identified the cases of 100 pregnant women who were denied emergency service in different states.)

How have healthcare providers become part of this apparatus of criminalization? Are there certain things they have to report if they notice them? — Anonymous | Why doesn’t federal HIPPA protect women from states accessing their medical records? — @cyndtrueme, on X

Healthcare providers are the primary gatekeepers for this whole thing: Of the over 1,000 pregnancy-related arrest cases that I studied, 75 percent originated by a healthcare provider making a report.

There are two federal laws to consider: HIPAA and CAPTA. HIPAA is basically a record-sharing law that places some limits on when medical information can be shared. In general, without your permission, information can only be shared when a person thinks a patient is a direct threat to themselves or others. Healthcare providers have made reports based on their belief that a fertilized egg, embryo, or fetus is a child facing imminent harm.

CAPTA (the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act) provides federal funding for the “prevention, assessment, investigation, and treatment” of child abuse. Many healthcare providers assume (or are advised) that CAPTA specifically requires that states define substance use during pregnancy as child abuse, and mandate reports to authorities, but this is incorrect. CAPTA does not require prosecution, drug testing, or filing abuse reports of babies exposed to drugs in utero.

What lies ahead?

The GOP’s official policy platform adopted at the RNC wants more states to establish ‘fetal personhood’ laws. Can you explain what the impact of this would be? — Anonymous

The GOP platform endorses the idea that the U.S. Constitution defines fertilized eggs, embryos, and fetuses as full legal persons. (Editor’s note: Courts have not recognized this conservative interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment, but there are signs that several justices are open to it.) I can’t overstate how impactful this would be. Anybody with the capacity for pregnancy, or who even looks like they have the capacity for pregnancy, would be suspect at all times, and lose the right to medical privacy. They would be banned from doing anything considered (rightly or wrongly) unsafe for a pregnancy, from a seemingly endless list of foods and beverages that are off limits, to forms of medical care including abortion. They would lose the right to medical privacy, and we would nullify advance directives (legal documents where a person states their decisions about life-sustaining care should they become incapacitated) during pregnancy. They could be fired from jobs deemed unsafe. Pregnant people who are abused by their partners could be charged for failing to protect their “unborn child.”

You can’t have fetal personhood and full legal recognition of people with the capacity for pregnancy at the same time: You are a womb before you are a person.

The bulk of the legal action establishing fetal personhood comes from states. One horrifying reality is that homicide is a leading cause of death for pregnant women, usually at the hands of their intimate partners. Instead of focusing on the factors that make pregnant people more vulnerable to homicidal violence, 38 states have responded by defining fertilized eggs, embryos, or fetuses as potential crime victims. The legislation is sometimes inspired by specific cases that get a lot of press coverage and cause public outrage—most often involving a white victim. For those of us who care about intimate partner violence, this might seem like a great solution to a terrible problem. I argue, however, that these laws are trojan horses, establishing fetal personhood in the criminal code under the auspices of protection. In turn, these very laws have been used as precedent to establish fetal personhood elsewhere in state law, and have been used to punish pregnant women deemed to have endangered or harmed their own pregnancies.

Are there grassroots groups that you see are doing a good job fighting against this? — I’m worried, from Ohio

It is easy to feel overwhelmed when I think about the work that needs to be done. Thankfully, none of us have to do this work alone, and there are many groups and organizations fighting back. There are two legal advocacy organizations worth looking into: Pregnancy Justice provides legal defense, guidance, resources, and education for cases involving pregnancy criminalization and CPS reporting. If/When/How also does amazing work on legal defense in abortion cases, and they operate both a legal help hotline and a Repro Legal Defense Fund to help cover bail and legal fees.

There are also some local and state-specific groups working on this, including Healthy and Free Tennessee, Sister Reach, and Sister Song, which focuses on the South. One of the most powerful things you can do right now is to get involved with your local abortion fund or practical support network. Not only do they help fund abortions and make arrangements for people who need support, but they also support folks who want to continue their pregnancies, give birth, and parent their children. They are the grassroots backbone of the reproductive justice movement.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.