“Time Is of the Essence”: How States Can Shore Up Mail Voting

An expert in election procedures unpacks how states should scale up mail voting, and how they should make sure no one is left behind.

Daniel Nichanian | March 24, 2020

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

Tammy Patrick unpacks how states should navigate the challenges of scaling up mail voting, and how they can make sure no one is left behind.

As many states postpone primaries due to the coronavirus outbreak, Oregon still plans to hold its May elections. “Because Oregon votes by mail, we do not have to be concerned about social distancing issues at polling places that so many other states are struggling with,” Secretary of State Bev Clarno said last week. “Many states are looking to implement our vote by mail system as a safer way to conduct elections in November.”

Oregon adopted a vote-by-mail system in 1998, and four other states have followed since (Colorado, Hawaii, Utah, and Washington). In these states, all registered voters receive a ballot; they then mail it back or drop it off at a designated location.

Calls to expand vote-by-mail nationwide are now ubiquitous in the face of social distancing.

California is moving in that direction. Officials in Arizona and New Mexico want authorization to send ballots to all voters. Advocates and scholars made the case for universal mail voting weeks ago. And some federal bills would help states get there.

In many states, though, implementing vote-by-mail would require a lot of work. It is a shift that raises challenges ranging from logistics and capacity to concerns about voter access and safeguards against suppression.

To unpack these challenges, I talked to Tammy Patrick, a senior adviser at the Democracy Fund who in 2016 co-authored “The New Realities of Mail Voting” with the Bipartisan Policy Center. A former elections administrator in Arizona, Patrick was appointed to the Presidential Commission on Election Administration by President Barack Obama.

We discussed how states should navigate the logistics of expanding mail voting and ensure that no one is left behind. Our wide-ranging conversation is transcribed below.

“Time is of the essence,” she said. “Each individual state is going to have to look at exactly what their capacity is to get this stuff out.”

That’s largely because states are starting from vastly different rules. Some states such as Arizona would have little trouble implementing all-mail voting since mail voting is already widespread there. But many others, such as New York, have little experience processing large numbers of mail votes. In fact, in 17 states voters must still provide an excuse when they request an absentee ballot — a basic obstacle to scaling up the availability of mail voting that Patrick called on states to lift. (In one of them, Virginia, lawmakers passed a bill ending this requirement in February; it now awaits the governor’s signature. Pennsylvania took that step last fall.)

Patrick laid out basic logistical building blocks that states must promptly work through if they are to increase the availability of mail voting, let alone move toward Oregon’s system.

Who will print the ballots? How will instructions be designed? Will the return postage be prepaid? Who will process applications, stuff envelopes, and open them upon return, especially in small offices that lack elaborate equipment? Will voters be able to confirm that they sent ballots on time? And how will counties make sure to reach out to voters about mismatched or missing signatures before throwing away a potentially valid ballot?

Addressing these questions is crucial to ensuring that all eligible voters access and cast ballots. In 2018, Georgia’s populous Gwinnett County drew headlines and lawsuits for rejecting a high number of mail ballots, predominantly from people of color. Onerous requirements, missing resources, insufficient assistance, or a failure to check in with voters about potential issues could end up excluding many voters. Conducting such check ins is also important to guard against fraud, Patrick noted.

Advocates have also warned that even vote-by-mail systems need to retain in-person voting centers and in-person services, which some people need and others are likelier to use. Those must now also be retooled due to the pandemic, as the Brennan Center laid out in an extensive report last week.

Patrick agrees. “States that have all-mail elections have offered some level of voter-servicing to cover eligible voters who may need personal attention,” she said. “You would just want to always make sure that there is still… some in-person solution for voters so they don’t fall through the cracks.” As examples, she pointed to Native voters with non-traditional addresses and to more transient voters who may need to update their registrations.

Voter registration also still largely rests on in-person interactions at motor vehicle departments and other agencies and by nonprofits that step up in places where public authorities do little outreach. Many states are behind when it comes to letting people register to vote or update their registrations online.

“There are a variety of solutions out there,” Patrick said. “It’s just we all are going to have to be really creative and I think everyone’s head is reeling right now with the implications of what we’re facing.”

The Q&A was condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

—

As some states postpone their primaries, there are growing calls for states to ramp up vote by mail. States have very different rules at the present in terms of the availability and scope of mail voting. What would it take for states to move to a vote-by-mail system?

Right now you have two extremes. There are five states that already do all vote by mail, and where everybody gets their ballot mailed to them.

There are other states, like California and Arizona, where large percentages of voters are already voting by mail, 70 to 80 percent of them. It would be easier for them to scale up.

But then when we look at the 17 states that require an excuse in order to vote absentee, numbers are very low; maybe single digit percentages of their population are voting by mail currently. It would be the most difficult for those 17 states to really ramp up in the same kind of way. [One of those states, Virginia, has passed a bill removing the requirement. It is on the governor’s desk.]

So there’s really a tiered approach: If this were to roll out, it would be easier for some states, and far more difficult for others.

What about the states between these two ends of the spectrum, between those states where all or most people receive a mail ballot and those states that still require an excuse to vote?

That interim is really a mixed bag. In most cases, voters have to still put in an application each time they want to vote by mail. What happens then is that more and more voters send in applications. When a tipping point happens and local elections offices can’t physically process applications in time, states establish a permanent list: When I lived in Arizona, I said I permanently wanted to get my ballot in the mail. Now in Arizona and California, they have 65-75 percent of voters getting their ballots by mail. At some point, it doesn’t make sense to have a polling place in every precinct if few of your voters are showing up in person. That’s when Colorado, Washington and others went to all vote by mail, but still have some in person options if we need to get a ballot replacement or need some additional assistance.

When you have everyone on a permanent list, that gives you the efficiencies in both time and resources to be able to put it towards getting the ballots out. For instance, in Georgia, they just moved their primary date; if they decide everyone has to mail in an application to get their ballot by mail, those local offices are going to have thousands if not tens of thousands, and in the large areas hundreds of thousands, of applications to have to process. That’s going to take a lot of time and resources and energy, as opposed to just mailing everybody a ballot to begin with.

So that argues for sending every registered voter a ballot, rather than waiting for applications. How should we keep the huge range in current practices in mind when thinking about what states should prioritize, given the time left until the remaining primaries and until November?

A lot of it is going to have to do with timing. Time is of the essence. It’s going to be difficult for the low participation-tiered states to ramp up and have voters make a request for the ballots and get the ballots mailed out and processed in time. Many of these small offices, it’s one election official (and they don’t just do elections, they’re also the clerk of the court and the assessor). For that person, they very well may be taking the ballot, folding it up by hand, putting it in the ballot envelope, hand-addressing it and mailing it out because now they may have a dozen or two dozen. If they suddenly have a few thousand of them, there just aren’t enough hours in the day.

Each individual state is going to have to look at exactly what their capacity is to get this stuff out. Do they have the print vendors and the industry support set up?

You’re describing very practical challenges, that this is about figuring out basic building blocks, like who prints these ballots and stuffs the envelopes.

Places like Nevada where they’re using a touchscreen voting system for their early voting, they actually haven’t been printing up ballots for those voters. That further complicates the challenge to moving solely to vote by mail for states that have a lot of voters that vote early in person and are not using paper ballots. For the states that are already used to printing up paper ballots, the challenge will be actually getting ballots mailed out. That’s where you run into challenges with buying envelopes by the millions, and it’s not like these are just regular old envelopes that you can go down to Home Depot and buy or to Office Depot.

If a state that now has 3 percent of their voters vote by mail decides we’re going to go all vote by mail, if they have poorly designed envelopes that have a lot of statutory requirements on all the language that has to be on there (the affidavits and all these things that we know can be a problem in going through the Postal Service mail stream), if they are just going to ramp up their existing program that doesn’t follow best practices, they’re going to have a lot of problems. Bad design is one of our biggest issues right now. If, however, states look to the other states that have already done this and have learned their lessons, we’re going to be far better off.

You’ve talked about challenges with processing applications (which can be reduced by sending a ballot to all) and with sending out the ballots. What about when voters return them?

The one good thing in all of this is that we don’t have to worry about whether or not the postal service can service that volume, because they can. Even if they had an influx of 300 million pieces, it’s nothing like their peak season, which is the holiday season. If the pandemic slows down delivery standards, there could be a slowing of the process; that’s where we need to make sure best practices are in place.

I think best practices in the return of the ballot is, one, prepay to postage if you can (that’s what Maricopa County does, what the state of Washington does).

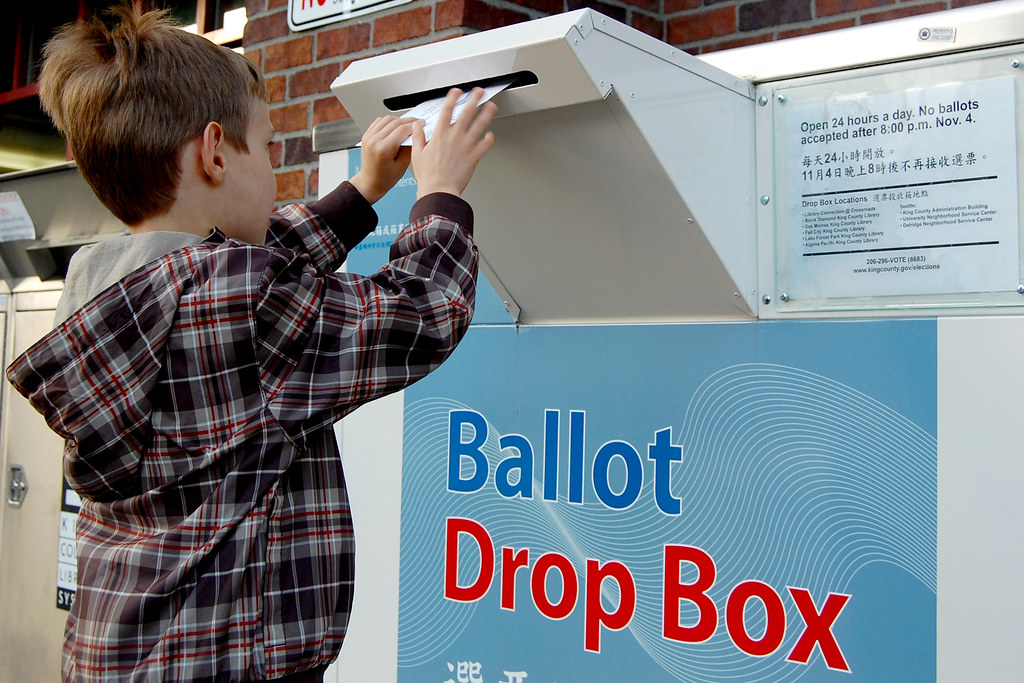

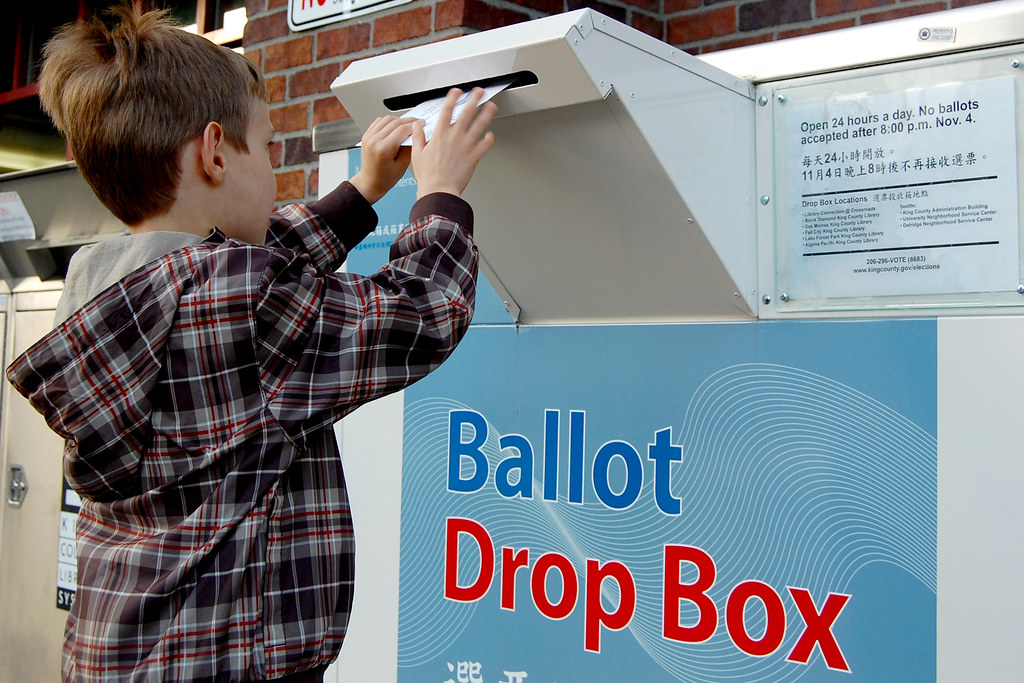

Allow for the ballots to come in after election day with appropriate documentation that they were mailed on time: Voters can mail back their ballot and have a postmark or other postal service data to make sure that their ballot was mailed by the close of the polls on Election Day, and that we’re not rejecting a ballot that comes in on Wednesday for Tuesday’s election. And also making sure that there are dropboxes to return them.

It’s also that states have a process in place for voters to remedy any issues. Some people call it the curing of the ballot: If a signature doesn’t match, election officials are reaching out to that voter in order to find out, did they really sign it and their hand was in a cast (which is what most of the answers were when I called voters), or is the voter going to say that I never signed my ballot, I haven’t voted. The curing is both making sure that an eligible ballot isn’t disqualified because the signature doesn’t match, but it’s also a security measure to identify if there was someone intervening on that voter’s ability to participate.

If more and more states move to a vote by mail situation, results will be delayed, because people will take longer in getting their ballots back in, and then they have to be processed. I think that no matter what happens in November, everyone’s just going to need to be patient and make sure that all the eligible votes that are cast have time to be processed and counted accurately. When you talk about places like New England or Michigan, Wisconsin, elections are conducted at the very localest of levels. It’s in the village, in the town, maybe a township, and very rarely at the county level. When you have those very small units of government conducting the election, they don’t have central tabulation equipment to count ballots quickly. They would have the ability to do it if they’re given the amount of time it takes in order to do that kind of tabulation.

—

You just mentioned dropboxes, and earlier you talked about all-mail states retaining in-person options. Alaska’s Democratic Party has announced it is cancelling all in-person voting for their primary, and replacing it with all-mail voting. So why do you think it’s important to maintain ways to vote in person?

Offering an in-person alternative has traditionally been important for voters who may need assistance in making certain that their registration is current and correct so that they get the correct ballot, or in overcoming obstacles they may face based on limited English proficiency or a disability. States that have all-mail elections have offered some level of voter-servicing to cover eligible voters who may need personal attention.

Voters need to have an opportunity to come in person if they need to to remedy any problems that might arise, and to drop off their ballot. In Arizona, the majority of voters tend to not mail it back, they tend to drop it off on election day at the polling places. Solutions may look more like drive-thru voting than what we consider a polling location looks like. I don’t see cancelling all in-person options as a possibility in November.

What other safeguards are needed in the mail voting system itself to ensure it leaves no one behind? Besides people who may need in-person assistance, as you mentioned, I’m thinking of people who may have trouble accessing mail. What have we learned from states, and what should new states be thinking of, in terms of guaranteeing everyone’s access to the ballot?

We know that in rural America and in Indian country non-traditional addresses can be a challenge for mail delivery and for addressing for voter registration purposes. Those are some known challenges that are being worked on. And so if a state were to move more to vote by mail, they would just want to be very conscious of that and work with both tribal leaders and their rural communities to make sure that it’s well defined where voters get their mail, whether it’s at a PO Box, or a cluster box like we have in in some areas.

We also know that homeless populations, individuals that are in shelters and things of that nature are also an additional challenge. And so just making sure that the already identified populations are being taken care of. Another one are care facilities and nursing facilities, which are not going to be polling places because we don’t want to send in the general population when we have the vulnerable population living in those facilities. Following some of these best practices that states that have done this have worked through is going to be really, really important.

One specific example of ballot access is that many people in jail and prisons can vote, for instance if they have not been convicted yet, which typically though not necessarily involves absentee voting, but often people aren’t able to access ballots. The Intercept just reported on this in Arizona. To what extent is shoring up mail voting, and putting in place this strong infrastructure, helpful for people to exercise their rights in spaces like prisons and jails?

For the last couple of years, felony re-enfranchisement has gotten a lot of attention. For me, it’s just as important and critical that voters who are awaiting trial have the capacity to interact. They haven’t had their rights taken away, they have every right to participate. I think that when there is a more robust system in place for absentee voting or vote by mail, all elements of the population would benefit, as long as everyone still has a focus on those populations, like incarcerated individuals, like voters in Indian Country, like voters in nursing facilities, that might need some additional attention to make sure that their rights are being equally represented.

Another challenge is that in-person interactions are central to how we think of registration, not just voting. Sme states don’t even have online voter registration. Even those that have people going to DMV or other government agencies, and automatic voter registration still often depends on those interactions. There are grassroots registration drives. If you deemphasize in-person interactions, what then can be done to protect registration?

I will tell you this is one of my big concerns. Currently, for those places that don’t have automatic or automated voter registration, we rely very heavily on our third party groups and nonprofit organizations and the political parties to help with voter registration. Because so many of those rely on that in person interaction (standing in front of the library, being at the county fair), those sorts of things are really not going to be happening right now. So my concern is exactly that states that don’t have an automatic or automated process will not get as many people registered to vote.

If the end goal is making sure that every eligible voter is registered and that their registration is current, how do we do that on the social media platforms and through other electronic means, if we’re not going to be able to have those in person interactions with people? Everyone is having to rethink all of the activities that we’ve done in the past.

Some states have not implemented online voter registration. Can they do that by the fall? What else should states be looking at?

With everything in elections it all kind of depends on the state. There are some states that have updated their systems with a vendor that has an online voter registration module, those states are more uniquely positioned to be able to do it quickly than a state that’s using their 20-year old statewide voter registration system; they will not be able to get it stood up in time. And that’s where we need to try and be creative and think through what are the best ways in which we can get people registered and whether that’s having a state make sure that they join ERIC and can identify unregistered voters on their DMV rolls and reach out to those voters proactively.

There are a variety of solutions out there. It’s just we all are going to have to be really creative and I think everyone’s head is reeling right now with the implications of what we’re facing.

There are many reports in recent years of voter suppression, poll closures, disenfranchisement laws, which is to say about public authorities actively making it difficult for certain groups to vote. Now, a lot of what we have discussed would require good faith efforts on the part of state and local governments, lawmakers to change the law, and administrators. So there’s an asymmetry here between some of what’s been happening with voter restrictions, and what is needed at the moment. How do you think about this concern that some people may have that public authorities in many places are not good faith actors when it comes to voting laws?

I think, in the last five to seven years, there has been a lot of changes in election laws and policy across the country. More states have online voter registration. More states have automatic voter registration. More states have no-excuse absentee by mail. More states have in-person early voting. So opportunities for voters to vote and register, thankfully, I think are growing. That’s not to say that there aren’t specific strategies in some states to implement really strict voter ID, or other methods that would curtail certain people from participating. We now are all finding ourselves in a place and time where I understand that we need to think critically about the changes that people are implementing. I know for myself, I can only move forward with good faith efforts and try to speak on behalf of the voters to policymakers and policy implementers. There tends to be a blurring of the lines between the people who are making the laws and the ones who have to implement the election under those laws, and sometimes those two get conflated, and that’s not always necessarily fair. And that’s why I think a lot of election officials in some places are very happy when friendly litigation comes along.

In many states what we talked about would require changes in law. How much can be done, then, do you think, without needing a statutory change?

First, is there the legislative political will to be more expansive and remedy some of the ways in which voters are able to interact with the franchise? If there isn’t, under emergency powers, what can a governor’s office do? And what can a secretary of state or a state board of elections do with their administrative powers? We’ve seen in the past secretaries of state issue directives to the county boards with the local officials on how to manage certain things. It’s all going to be a question of what is the action that’s being proposed, and then who has the responsible statutory authority to make that decision.

—

In that spirit, I’d like to return to specific groups of states and how they can confront these challenges. For states that already have significant mail voting, like Florida, Texas or Arizona, but that do not send ballots to every registered voter, what would it take to put in place an Oregon-like universal mail program by November?

Arizona, 60 to 80 percent of their voters are already getting their ballot by mail. States like Arizona are positioned to go all vote by mail, they have the infrastructure, the local county governments are already processing large volumes; the county I was in [Maricopa], we had one and a half million ballots that we would send out, so adding another 500,000 to that is nothing.

If the states that already are close to 40 or 50 percent of their voters are voting by mail, I think that they could move to a full vote by mail system by mailing out ballots to everybody and then offering the in-person solutions or in-person assistance for voters before election day.

I think that Florida would probably be able to do it if they’re given enough time and resources. They also have a lot of early in-person voting, so it would be a little bit harder for Florida, but because they do have a third of their electorate voting by mail, the large jurisdictions have the right kind of central tabulation of equipment; they have the procedures and protocols set up to be able to expand. So I think they would be able to pull it off if given enough time and resources. But in some of these jurisdictions, people are literally hand opening up every single ballot envelope, and when you have a few hundred thousands of them, it takes a while.

Let’s move to the states with the smallest amount of mail voting, states such as Virginia, which is now in the process of enabling no-excuse absentee voting, and other states that have not even done that. Let’s say they do in coming months. Still, you suggested it may be difficult for them to go all-mail by November. So what is it that you think they should think about in terms of how to protect voting?

I think those states should all remove the excuse requirement; if they don’t have the legislative support to do that, they should be designating which reasons voters can use for this pandemic. So is it they need to check the box for 7a, or what is it on the application?

They also need to make sure that applications can be done online or by the telephone. I think that the recent [U.S. Senator Ron] Wyden bill that said applications can be sent electronically is really helpful, as well as making sure that voters could call in and request a ballot be mailed to them. and then making sure that they are implementing best practices like the design of the envelopes to make sure that they’re clearly marking their envelopes with the official mail logo so that the postal service knows these are ballots and can handle them appropriately.

So all of the practical questions you talked about come into play the most in those states since they have not done anything approaching the scale of a significant mail program.

Yes, it really comes into play in all the states that aren’t currently using best practices in their design. Virginia has had some major changes in the last couple of years, and they actually use ballot tracking systems, so they’re not as far behind as they were three or four years ago. But a lot of the New England states that haven’t seen a lot of vote by mail, and quite frankly, New York—the state of New York has very little vote by mail. Michael Ryan in New York City would have a very difficult time ramping up all vote by mail for all the boroughs by November.

So then what does expanded mail voting look like in New York?

It is the case that you could mail out a ballot to everyone in New York City: They have other mailings that they do, they mail out other materials to all of their voters.

But you would want to make sure that you still had some in person activity being offered because the population, one, is so vast, two it moves very frequently. So there are things that could be done, but you would just want to always make sure that there is still, particularly in New York State, some in-person solution for voters so they don’t fall through the cracks.

What is the role of the federal government in all of this? We’ve mostly talked about states, but you also mentioned Ron Wyden’s vote-by-mail bill.

There are a couple of things that the federal government can do. One is to recognize that any bill that puts additional onus on the states and localities to move to a vote by mail situation needs to have some support monetarily and some resources. I don’t think there are counties out there that have the capacity or the ability to stand up full on vote by mail on their own.

If they are going to contemplate putting forth some legislation on vote by mail, that it should be promoting the best practices, even saying they should use ballot tracking and full service through the postal service. We already pay for the postage for military and overseas voters, so that is certainly something that could be contemplated for all vote by mail. I don’t foresee this Congress doing that, but I throw that in there.