Illinois Bans ICE Program. But This Reform Is Not Yet Taking Off Elsewhere.

Illinois prohibition against 287(g) contracts comes two years after California’s ban.

| September 5, 2019

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

Governor J.B. Pritzker signed a law that bans county governments in Illinois from contracting into ICE’s prized 287(g) program, which deputizes some local or state officers to act as federal immigration agents.

“Illinois is traditionally a welcome state for immigrants,” said Fred Tsao, a senior policy counsel for the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights. “We and many of our allies have done a pretty good job organizing immigrant communities to have a voice in state level policy.” Tsao added that the 287(g) program stretches the duties of local law enforcement, and harms residents’ trust in and ability to turn to local authorities.

Immigrants’ rights advocates have made a similar case elsewhere, to some political success, from Arkansas to Maryland. “It creates a climate of fear, particularly for the Latino community and communities of color,” Jose Perez, the deputy general counsel of LatinoJustice PRLDEF, told the Appeal: Political Report in October.

There was already no Illinois county with a 287(g) contract when the law (House Bill 1637) passed. But the program has rocked local politics in Illinois in the past, and a county was on its way to joining: Sheriff Bill Prim of McHenry County (a GOP-leaning area north of Chicago) applied for membership last year. The law effectively interrupts that application.

Prim already detains people arrested by ICE in the county jail he runs. In 2017, he faced multiple lawsuits for not releasing individuals based on ICE’s requests not to; the lawsuits were later dismissed. Illinois had just adopted the Trust Act, which prohibits local authorities from honoring ICE detainers, which are warrantless requests.

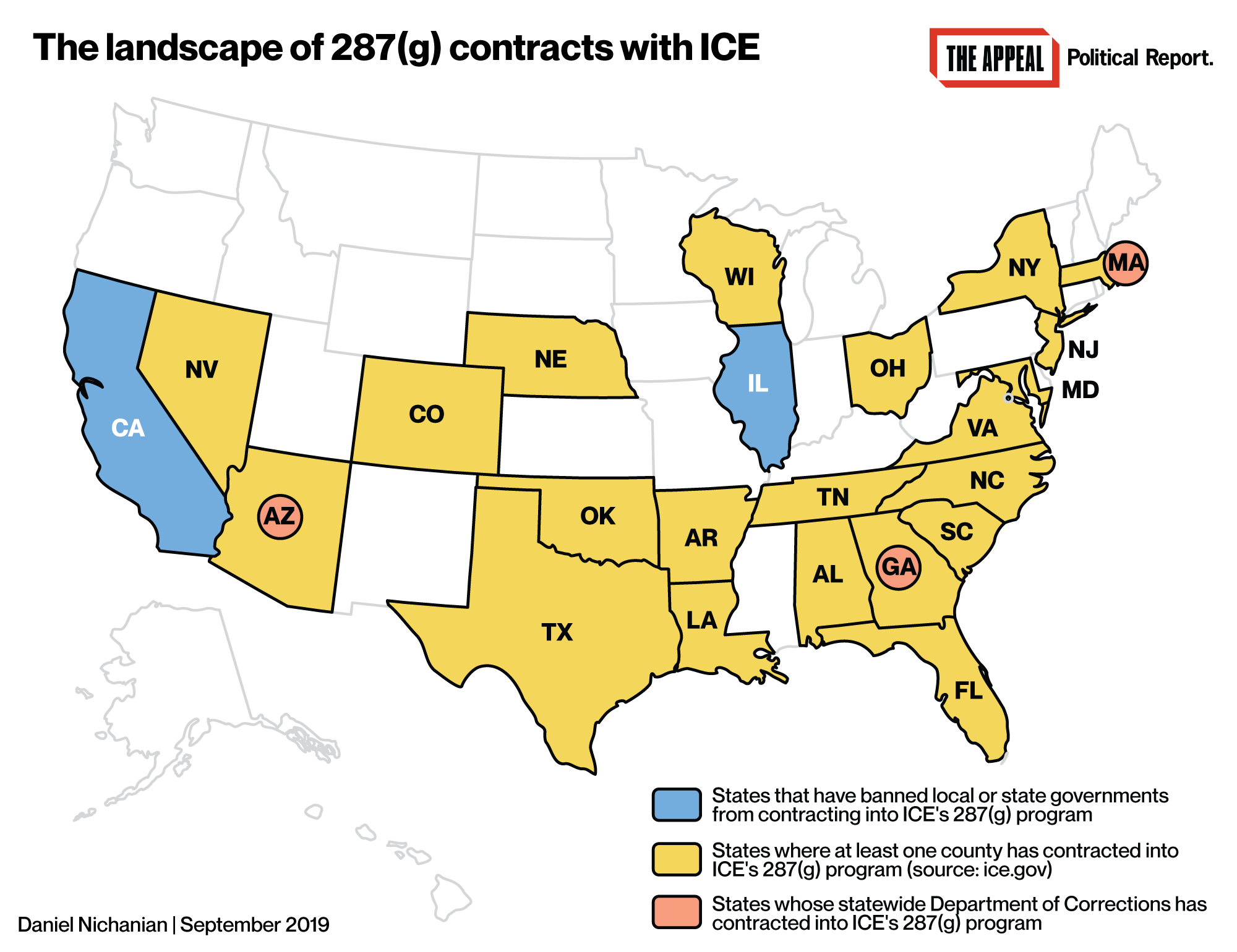

The state’s new legislation extends the Trust Act by prohibiting another form of cooperation with ICE, 287(g) contracts. Less than 3 percent of all counties nationwide have joined the program—a decision that is often, but not always, in the hands of county sheriffs—so membership remains an unusually tight relationship.

California adopted a ban against these contracts in 2017, soon after President Trump’s election. But the reform has not taken off since as a staple of lawmaking in Democratic states, let alone in states under divided or Republican control, at least not until this Illinois law.

This year, Colorado Governor Jared Polis threatened to veto a bill this year unless its sponsors removed a ban on 287(g) contracts; the final bill he signed did contain other restrictions on cooperation with ICE. There was no legislative movement elsewhere. In New York, the Democratic legislature did not pass a proposed ban this year, and the Republican sheriff who signed the state’s only 287(g) contract is coasting to re-election unopposed this fall.

And in Massachusetts, where Democrats enjoy a veto-proof legislative majority, lawmakers have repeatedly ignored or killed the Safe Communities Act, which includes a measure that would ban 287(g) within the state. “As long as the Massachusetts legislature continues to punt, they are being complicit in Trump’s racist deportation agenda,” said Jonathan Cohn, the chairperson of the issues committee at Progressive Massachusetts, a group that advocates for this bill. “Inaction is the result of a legislature and leadership that is unrepresentative of the diversity of the state.”

Massachusetts is one of just three states (alongside Arizona and Georgia) with a statewide 287(g) contract through its Department of Corrections, which runs state prisons. The DOC, which is run by an appointee of Republican Governor Charlie Baker, renewed its contract this summer. In addition, three sheriffs have partnered their counties (Barnstable, Bristol, and Plymouth) with the program. All three are Republicans who represent jurisdictions Hillary Clinton carried in 2016, and all are up for reelection in 2022.

Opponents of 287(g) agreements also focus on county-level politics. In the 2018 elections, candidates for county executive and for sheriff in Maryland and North Carolina ran successfully on ending their county’s membership, and they followed through upon taking office. The program is at issue again in elections this fall.

Obtaining a statewide ban can enable immigrants’ rights organizations to shift more of their attention to the other ways in which ICE enjoys the assistance of state and local governments.

Advocates are working for Illinois to implement more restrictions on cooperation with ICE. The initial version of HB 1637, filed in January by state Representative Emanuel Chris Welch, contained measures that were later discarded to limit the information public agencies could collect, and barred local law enforcement from inquiring into people’s birth country.

But the state adopted a separate bill, besides the ban on 287(g) contracts: House Bill 2040 prohibits privately run immigration detention centers. “We will not allow private entities to profit off of the intolerance of this president,” Governor Pritzker said in June.

Tsao of the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights called for broader action against detaining immigrants. “Our view is that people shouldn’t be detained, period,” Tsao said. “Let’s allow people to be in the community if they’re asylum seekers with no place to go, let’s provide them with communities of care where they can be better integrated, if they have families to go to let them stay with their families. We should not be doing this, and especially not for profit.”