Court Watchers Prepare For the End of Cash Bail in Illinois

Advocates who lobbied for the landmark reform, which finally takes effect next week, are organizing to monitor detention hearings and make defendants aware of their new rights.

| September 13, 2023

On Sept. 18, Illinois will make history by becoming the first state to get rid of cash bail.

That’s when the Pretrial Fairness Act, which bars judges from making defendants pay money for their pretrial freedom, will finally go into effect. The act, which also creates a new process for prosecutors to petition to keep defendants behind bars, was part of a larger reform bill, the SAFE-T Act, that Illinois lawmakers passed in early 2021 and that sheriffs and prosecutors sued to block, delaying its original implementation date earlier this year.

But the state Supreme Court found the law to be constitutional in July, paving the way for cash bail to disappear from Illinois courts next week.

For the advocates who lobbied in favor of the law, some of the hardest work now begins to make sure that it actually reduces jail populations.

Matthew McLoughlin, an organizer with the Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice, said organizers held court-watching training sessions for activists throughout August to monitor implementation and gather information so they can defend the reforms from vociferous critics. He said the group plans to have between 20 and 30 people ready to court watch in nine counties starting next week, including Cook County and Winnebago, which have the two largest county jails in the state, with the goal of observing 75 detention hearings and 100 initial appearances in the first month of the law’s implementation.

“I really think the advocacy begins now,” McLoughlin told Bolts. “What we’ve found is that if the community doesn’t stay involved, we don’t actually get the outcomes we fought for.”

In all other court systems across the country, judges can require defendants to pay money as a condition of being released pretrial under the pretense that it will ensure they return for future court dates, a system that keeps people locked up when they are too poor to pay. Such pretrial detention can have lasting consequences, such as costing people their employment and housing—harms that fall largely on defendants of color who face significantly higher bail amounts.

For the Illinois activists who have been pushing to end this system, the ultimate goal is not eliminating money bond per se, but reducing the number of people jailed before trial. Court watching is a way to make sure the numbers actually decline. While judges can no longer set money bond after next week, they may still reach for other punitive measures in its place—electronic monitoring, for example, or simply deciding to detain people rather than release them.

“We are concerned with the spirit of the law being implemented and not just the letter of it, and that’s where court watching comes in,” said Briana Payton, senior policy analyst for the Chicago Appleseed Center for Fair Courts.

Once the law is in effect, if prosecutors want someone to be detained, they will have to file a petition and prove in a hearing that a defendant poses a “real and present threat” to a person or community’s safety or that they are likely to engage in “willful flight” from court dates to avoid prosecution. The hearings must be “individualized and robust,” explained Sharlyn Grace, senior policy advisor for the Law Office of the Cook County Public Defender. People accused of a crime have to be represented by “meaningful” legal counsel, Grace said, which means the accused and their lawyers have to have an opportunity to actually discuss the case together before the hearing. Their counsel must have the opportunity to present evidence and rebut the state’s evidence and case for detention or, in the case of a release decision, against any pretrial conditions like electronic monitoring or drug testing.

Electronic monitoring or home confinement, according to the law, can only be imposed if there are no other less restrictive conditions that would ensure people come to their court dates and don’t harm others.

The law allows counties to continue using algorithmic risk assessment tools that purport to rate people based on the risk they pose of committing more crimes or dodging court dates by comparing their characteristics with past court data. These tools are riddled with racist biases, but under the law, the assessments and what goes into them must be shared in open court and counsel can challenge the recommendations. The law says these risk assessment tools also cannot be used as “the sole basis to deny pretrial release.”

A judge must then make a finding about why a person should be detained or, if released, why restrictive conditions are necessary. The judge’s decision “is transparent and reviewable and can be contested,” Grace said; it can be appealed to a higher court.

These hearings will be substantially different from what currently happens when someone is assessed for bail. “Right now a lot of bond hearings in Illinois last minutes or even seconds,” Grace said, adding that some have been done over the phone or even email. Those who are represented by legal counsel often meet them for the first time in front of the judge, with little opportunity to explain their side or compile evidence.

The law requires detention hearings to happen in person except for when operational challenges or public health emergencies make remote hearings necessary, although advocates worry the exception will be used too broadly, especially given that the state supreme court recently announced that it will have to use remote hearings to deal with the increased volume of cases when it goes into effect. This new process will also require enough lawyers to represent all of the people going through these hearings. Some counties, Grace said, are under-resourced, but her office, which covers Chicago, created a new division and increased staffing to handle the hearings. “We’re ready,” she said.

The law also limits who will have to go through these hearings. The Pretrial Fairness Act requires that people charged with offenses other than felonies or Class A misdemeanors not be arrested and taken into custody at all, but instead given citations on the spot. It also specifies that people accused of misdemeanors and the lowest level of felonies can be arrested but should then be released from police stations with a court date. Grace said that will mostly apply to offenses like driving on a suspended license, retail theft, and drug possession. Only the moderate or more serious classes of crimes, including domestic violence misdemeanors like simple domestic battery or violations of protective orders, will go through the hearing process where the state can seek detention.

People currently in jail because they haven’t been able to pay a money bond handed down by a judge, meanwhile, will have the option to request a rehearing where they can ask a judge to, under the new law, release them without conditions. At that point the state can file a petition seeking their detention, but it will go through the same hearing process. It’s impossible to know how many will choose to request a rehearing, but “many” of the people in Illinois jails “will be entitled to release because they’re not in there for serious cases,” Grace said—they’re there because they can’t afford to pay bail.

In addition to fielding a team of court watchers to observe these hearings, advocates are also preparing for the law by raising awareness for people currently in jail who will be entitled to a rehearing starting next week. The Cook County Public Defender’s office recently held a training for all of its attorneys and staff going through the options for people with pending cases. The Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice has designed and printed know your rights guides the size of a business card with information about the new law and, crucially, the new rights people will have when they go through the system. Advocates are planning to distribute the guides to people most likely to be arrested, getting them out at legal aid offices, mental health providers, and harm reduction clinics. “We’re trying to get those in front of as many people as possible,” McLoughlin said, so “people are getting their full rights under the law.” They’re also lobbying for government agencies to send information to people in jail directly.

It recently became clear that advocates have their work cut out for them after the Illinois Office of Statewide Pretrial Services launched an electronic monitoring program in 70 counties on Aug. 20 as part of its preparations for the Pretrial Fairness Act, despite the law stating that such monitoring should be a measure of last resort. “There is no reason for Illinois to expand its use of electronic monitoring in response to ending money bond,” the Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice said in a statement responding to the ramp-up in electronic monitoring programs.

Electronic monitoring “defeats the purpose of being released,” Payton told Bolts. “It’s another form of incarceration.”

Through court watching, if advocates see that judges are veering from the purpose of the law by penalizing people who should simply be released, they can raise the alarm with the courts themselves and other people who are responsible for implementation. Community members can protest. Civil rights attorneys can bring litigation. Judges, many of whom are elected, may feel pressure from being watched. Such efforts have been successful before. In 2016, after two people held in the Cook County jail brought a lawsuit challenging the cash bail system for discriminating against poor people, the county’s chief judge instructed judges in July 2017 not to set money bonds that defendants couldn’t afford to pay. But the order had virtually no enforcement mechanism.

“Right off the jump we knew we needed to be watching the courts like hawks,” McLoughlin said. With the help of roughly 100 people trained to watch courts, his organization exposed several judges who weren’t following the order.

Court watching will also allow advocates the opportunity to gather insights and data on what happens in courtrooms after the reforms as a way to push back on misinformation and any campaigns to roll them back. Opponents of the Illinois reform, including state Republicans and law enforcement unions, have raised fears that ending cash bail will increase crime, and they unsuccessfully campaigned on the issue during the 2022 midterms. Their efforts, filled with incorrect information, got media outlets to run with the nickname “Purge Law,” after the movie franchise about a 12-hour period when all crime is legal, even using screenshots from the movie in stories.

A similar reaction greeted passage of a reform in New York in 2019, which barred judges from setting cash bail for most misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies. Studies of New York released this year found that the state’s bail reform, which the GOP and some Democrats have severely criticized, did not increase crime.

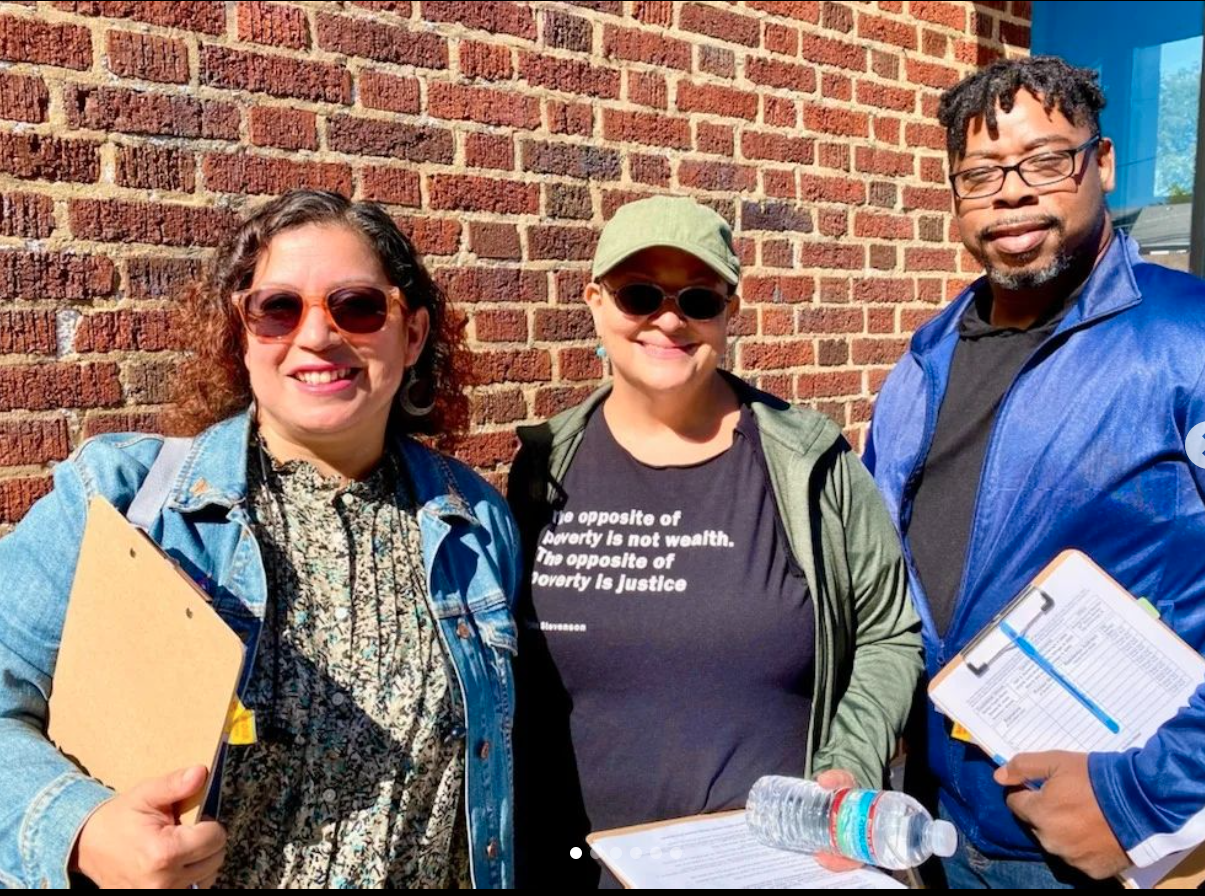

People who court watch in Illinois can report back to their neighbors and communities about what really happens after the law goes into effect. Activists also are planning on canvassing to get the word out about what the law actually does. In late August, they hit local farmers markets to hand out fact sheets and talk to people. They also plan to go door to door, hoping to speak to thousands of people directly.

All of that organizing could become important very quickly. The Illinois legislature reconvenes in October and November for a veto session, and McLoughlin expects “some half-baked proposals” to roll the law back. He expects to have to defend the law in future legislative and budget sessions as advocates have had to do in New York, where bail reforms have been rolled back twice since 2019. “I think we’re going to be juggling implementation and defense for the foreseeable future,” McLoughlin said.

“We are under no illusions that our biggest fight is behind us,” Payton agreed. “We know that our biggest fight is ahead of us.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.