How Illinois Housing Banishment Laws Push People into Homelessness and Prison

Organizers with past sex offense convictions are championing a bill in the state legislature that could end the cycle and roll back residency restrictions.

| January 16, 2024

James Orr was in his apartment in the Austin neighborhood on Chicago’s West Side one Wednesday morning in 2013 when he heard his phone buzz. “James, you have 30 days to move,” an Illinois state police officer on the other end told him. The 62-year-old, who had moved into the apartment with his wife in 2006 after finishing a three-year prison sentence, was incredulous. “What do you mean I have to move?” he asked. He had lived there for seven years.

As part of a previous conviction, Illinois required Orr to appear on the sex offense registry, one of five public conviction registries in the state. The sentence came with a litany of other restrictions that will follow him for the rest of his life. Orr can’t visit parks, forest reserves, schools or playgrounds and must pay a yearly $100 registration fee. He’s also prohibited from living within 500 feet of any school, playground, day care or childcare facility.

That’s why state police came calling in 2013. “You have to move, sir,” the officer repeated. “A day care moved [within] 500 feet.” Orr says he panicked and started calling around, trying to find a place to go. But each time he found an available apartment, police shot down the address saying it wasn’t compliant with Illinois’s dense web of housing restrictions.

Orr estimates he checked on more than 20 places but still couldn’t find a legal place to live by the time his month-long window to move drew to a close. He could continue to stay at an illegal address. But if he were caught, he’d be sent back to prison. He and his wife packed their belongings into a storage unit and moved in with his sister, but when he called police to update his address, they told him it was too close to a school. His only other option was to register as homeless—but in all his interactions with police, he says no one told him he could.

It often plays out like this: A person can’t report their address because it’s not legal. Without a legal address, they can’t register. When they don’t register, police pick them up and charge them with a new crime.

It took police another year to come knocking after Orr failed to find a legal address or register as homeless. A judge ultimately convicted him of failure to report a change of address, a class 3 felony, and sentenced him to seven years in state prison. It was the second time he’d been imprisoned solely because he couldn’t find legal housing; police once arrested him in his home during an address check after determining his apartment was in a banishment zone, despite them previously allowing him to register the address.

“How do you get out of it? How do you get out of the cycle unless you build you a house on a dirt road somewhere?” Orr told Bolts.

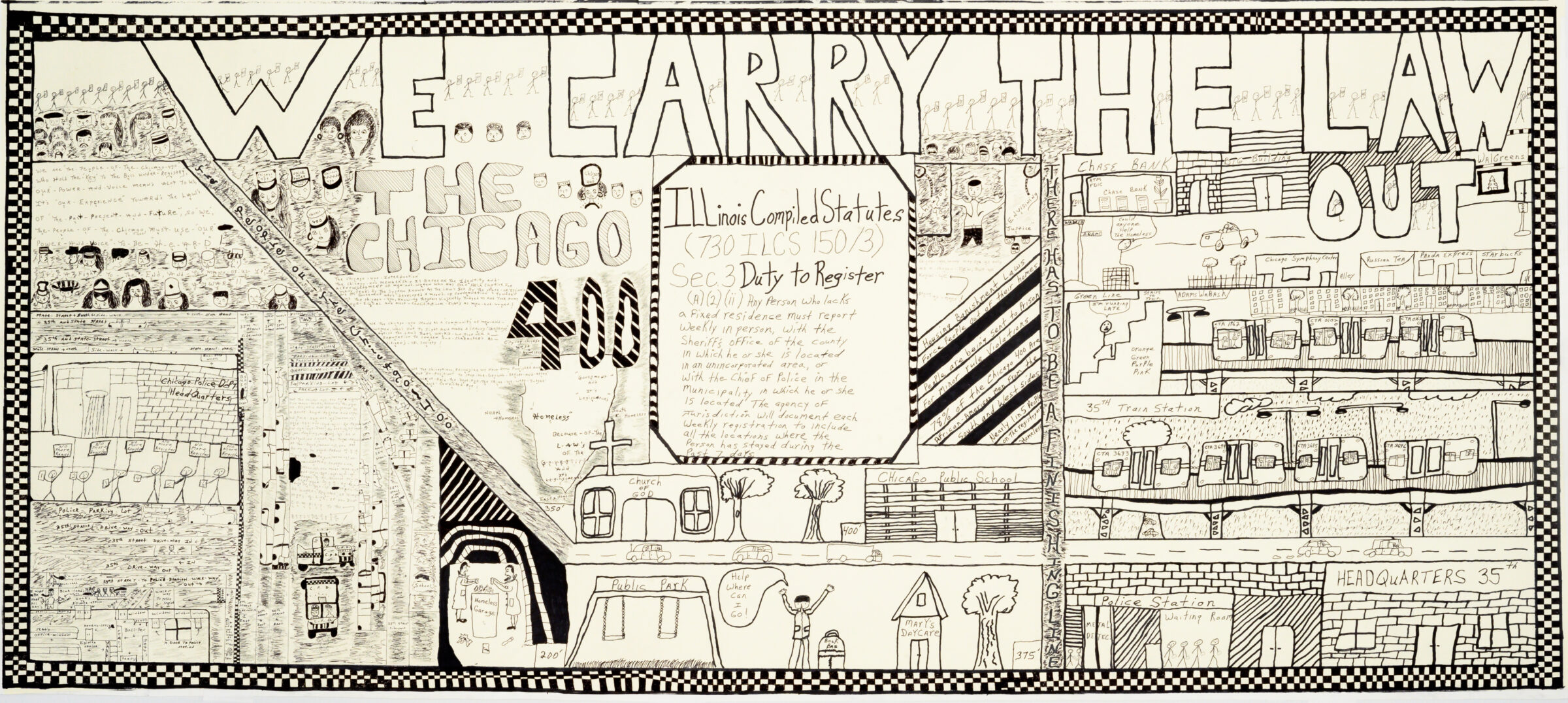

The expansive nature of so-called housing banishment laws in Illinois, in addition to a laundry list of other restrictions, make it nearly impossible for people with past sex offense convictions to find a place to live. Few available housing units exist that aren’t within 500 feet of playgrounds, schools, and day cares. As a result, Orr and more than 1,400 other people like him, predominantly Black men, are forced into indefinite homelessness across the state, cycled in and out of prison and relegated to an underclass with lifelong stigma.

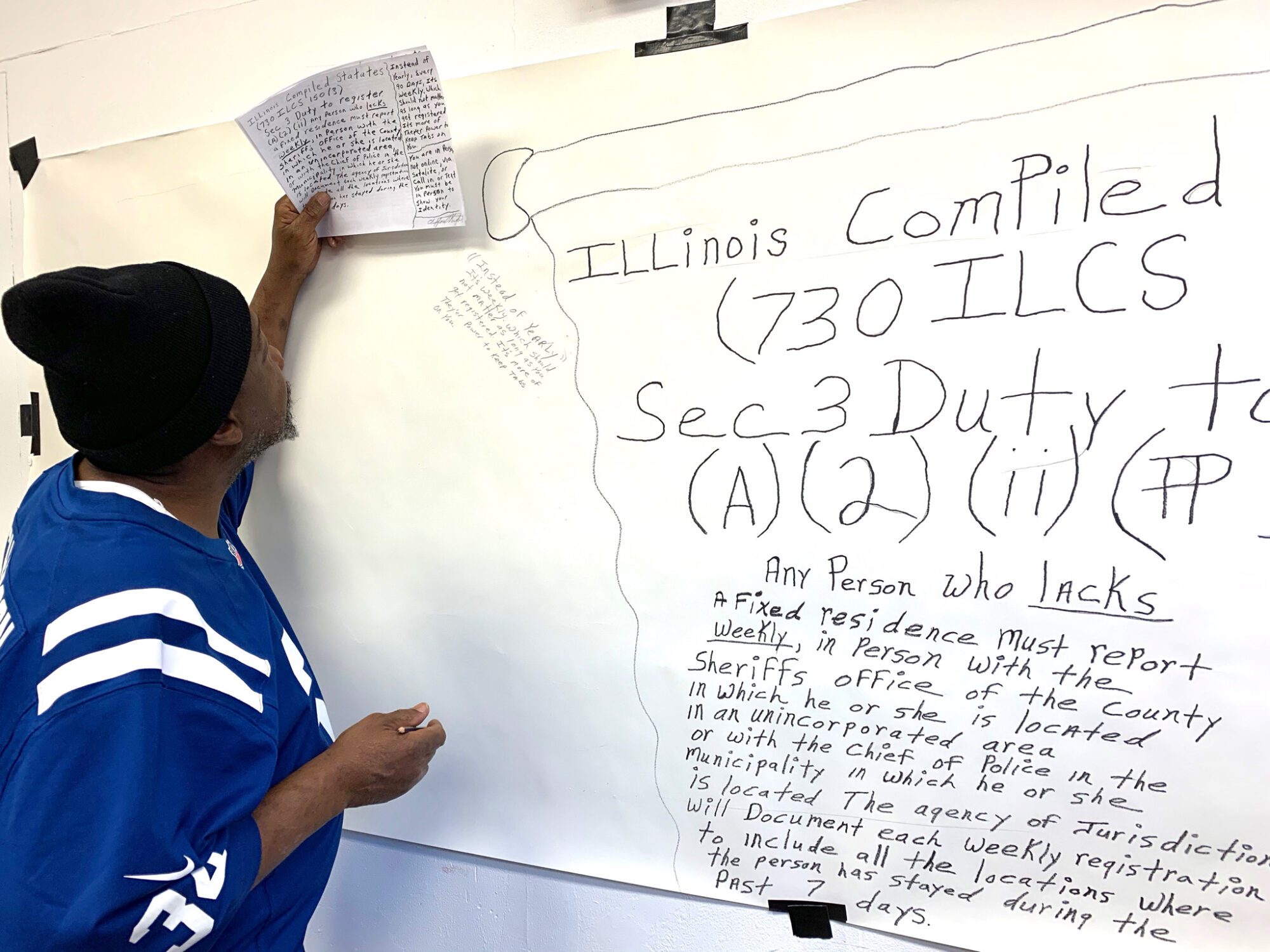

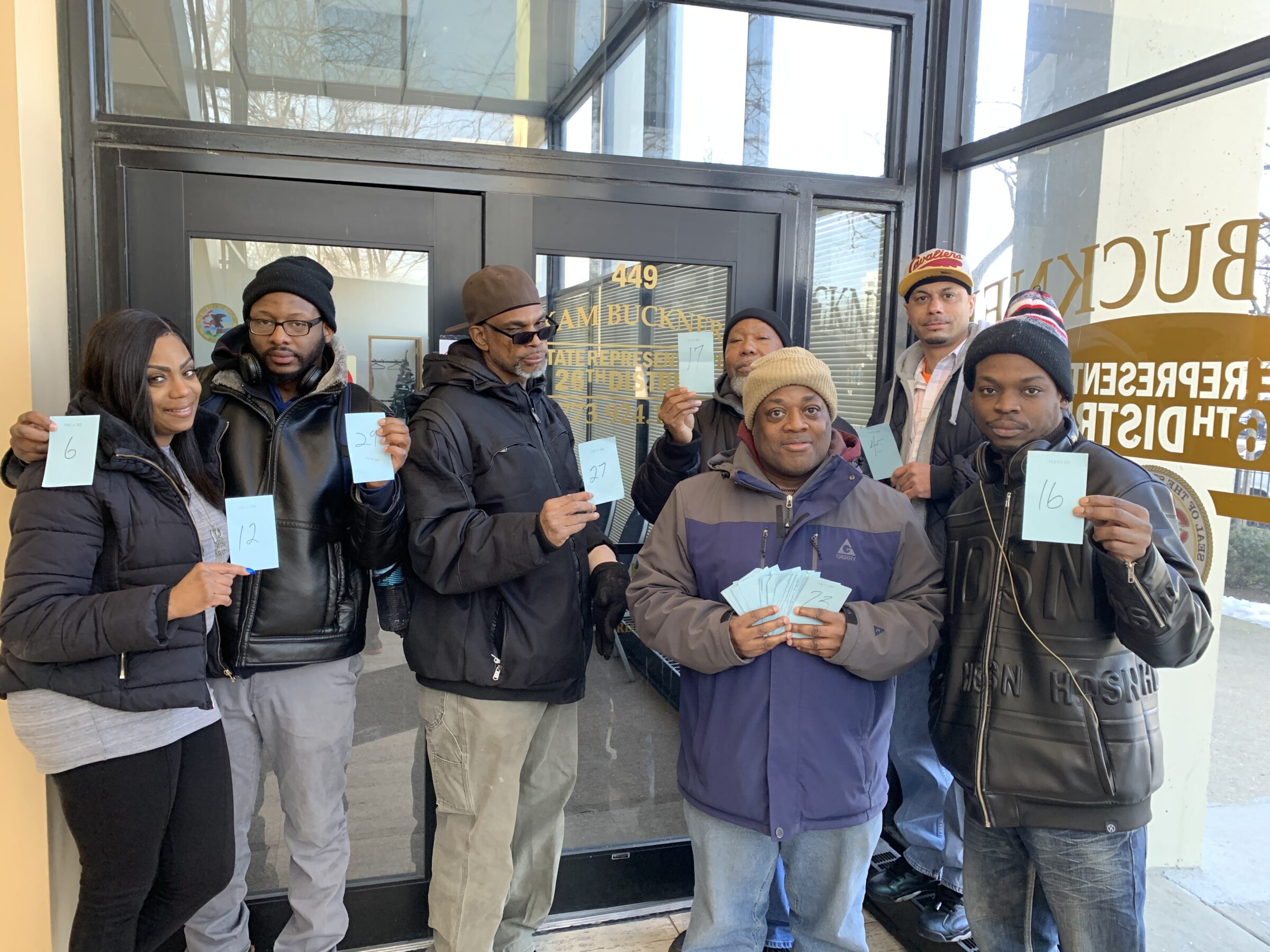

Orr and hundreds of other unhoused Chicagoans with sex offense convictions have spent years organizing against housing banishment laws and registry requirements with the Chicago 400 Alliance, a coalition of housing, reentry and victim advocates as well as social service agencies. The group’s most ambitious challenge to date is a bill pending in the Illinois legislature that would ease residency restrictions and expand housing options. The legislative session, which begins this week, ends in late May.

The bill would shrink banishment zones around schools and playgrounds from 500 to 250 feet and remove home day cares from the list of residency restrictions. Once a person finds stable housing, under the proposal, they also couldn’t be forced to move if their home later becomes part of an exclusion zone.

“The reality is that our current policies are not working,” Senate Majority Leader Kimberly Lightford, who is the bill’s chief sponsor, told Bolts. “They’re not serving who they should serve. It’s creating a crisis of homelessness and it does not make our communities safer.”

As an employee at the state department of corrections in the 1990s, Lightford helped create Illinois’s sex offense registry. But now, after years of enhanced penalties and restrictions, she said, “What we’ve done is disenfranchised a whole population of people.”

Orr still didn’t have housing the last time he got out of prison in 2017. His wife’s apartment wasn’t compliant with state residency restrictions, so at first he tried a shelter a few blocks from a police station. But when he stopped by the station to update his address on the registry, he heard a familiar refrain—no good, it turned out the shelter was too close to a playground.

With no other options, Orr opted to sleep in his wife’s car while he saved for one of his own. Within a few months, he’d scraped together enough to bounce from one hotel room to another. Seven years later, he says it’s an endless cycle. “I’m still doing the same thing I was doing when I first got out in 2017—sleeping in my car, staying in a hotel.”

Orr stays with his wife just two nights a year. He can’t stay anywhere for longer than two days a year, or else it’s legally considered a secondary residence. Orr and others who register as homeless must check in with local law enforcement on a weekly basis. Even if a person on a registry manages to find legal housing, exclusion zones are constantly in flux. People can be forced out at any time, regardless of whether they own or rent their home. Ubiquitous and often impossible to identify from outside, home day cares pose a particular challenge.

If a person’s housing becomes illegal, police generally offer a 30-day window to find a new place within the scope of the law—though that’s a courtesy, not a legal right. Two options exist for people still without housing at the end of that period: live homeless or return to prison.

Steven, who asked that his full name not be used for fear of retaliation, finished his prison sentence in 2007 and moved to Riverdale, a Chicago suburb south of the city. Housing was easier to come by there, since it’s less densely populated than the city. For years, he managed to find a legal place to stay with relative ease.

That all changed in 2019. He and his wife had been living in their apartment for five years. The pair dated in sixth grade, reconnected years later, and have been married for more than a decade. One mid-July day, police arrived to measure the distance between their apartment and a new day care that was opening up down the block. Steven says they told him his apartment was 28 inches too close. “It just got harder, and harder, and harder to find a place where I could stay. So I became homeless,” he told Bolts.

Every afternoon, after he finishes work as a peer counselor at an addiction treatment center on the city’s west side, Steven visits his family’s home. Each evening, after he says goodnight, he leaves again. Sometimes he stays with his mother, sometimes his sister, sometimes a friend—always couch surfing and never staying anywhere longer than two days. When his grandchildren ask why he leaves at night, he tells them he works the night shift.

“It hurts. I want to lay next to my wife,” Steven said. “I want to play with my grandchildren. I want to have fun with my children not just part of the day but, sometimes, all day. I want to wake up to them. I want to hear the noises, and the arguments, and the fussing. That’s what I miss most.”

The impact of Illinois’s housing banishment law extends far beyond people with convictions and shapes generations of families in lasting ways.

As the primary caregiver to an adult son with an intellectual disability who must comply with the abundance of housing restrictions and residency requirements, Cheri worries what will happen when she can no longer look after him. Those rules, coupled with a dearth of skilled nursing facilities with beds available for people with sex offense convictions, leaves her with virtually no viable options.

“It definitely puts pressure on the family,” said Cheri, who asked that her real name not be used to protect her family. “What are we going to do with these people? Just throw them away when their families are no longer able to take care of them? I mean, it kind of feels like they’re throwing all of us away.”

Cheri says the judge in her son’s case gave him three days to move after he was convicted and sentenced to probation, community service, and ten years on the sex offense registry. Her house was 11 feet too close to a home day care, so the family put it up for sale and spent the next ten months searching for a place to live. She says she lives every day “in constant fear that someone’s going to open up a day care, someone’s going to put in a park, wherever you live.”

The conviction, and the stigma that comes with it, creates instability in nearly every aspect of their lives, Cheri says. The punishment is lifelong. “We can’t go to museums. We can’t go to forest reserves, we can’t go to parks. There are family reunions that we can’t attend because he can’t be present.” It creates, she said, “a class of people who, no matter how hard they try to do the right thing, are just pushed down constantly.”

Over the past four decades, Congress ushered in a series of federal mandates that pressured states to vastly expand policies targeting people with sex offense convictions. This includes the Wetterling Act, named for an 11-year-old boy from Minnesota who was abducted in 1989. The measure, part of the infamous 1994 crime bill, required states to establish a registry for people convicted of sex offenses and other crimes against children. Megan’s Law, which followed the murder of seven-year-old Megan Kanka in New Jersey, mandated that states make their sex offense registries public.

Illinois lawmakers, for their part, passed into law a cavalcade of measures targeting people convicted of sex offenses. In 1986, the state began requiring people convicted of two or more sex offenses against children to record their information in a private law enforcement database. Lawmakers expanded the registry to include people convicted of any sex offense against a child in 1993, then again to include anyone convicted of any sex offense in 1996. Later that year, lawmakers made the registry public.

Each year, as legislators returned to Springfield, they tacked on new conditions. By 2013, people on the registries were prohibited from living within 500 feet of any facility “providing programs or services exclusively directed toward persons under 18 years of age,” working at businesses that photograph children, or participating in holiday activities with children outside their families, like handing out Halloween candy.

Every state maintains some form of public conviction registry and 27 have residency restrictions of some kind. But another 23 states have resisted such housing restrictions, which are not recommended by federal agencies and are opposed by numerous advocacy organizations, like the Association for the Treatment and Prevention of Sexual Abuse, the professional organization for researchers and treatment providers in the field.

A large body of evidence shows these measures do little to prevent—or even respond to—sexual violence.

According to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, eight out of every ten perpetrators of sexual violence know the person they harm. In cases with children, that proportion climbs to 93 percent—and the perpetrators themselves are often children. A 2009 U.S. Department of Justice bulletin states that youth under 18 comprise more than a quarter of all people who carry out sexual violence, and more than one-third of perpetrators when the person harmed is also a child. Four of ten survivors under age six are targeted by another child, according to a 2000 Bureau of Justice Statistics study. The report also finds that the most common age of sexual assault perpetrators is 14.

Yet survivors report sexual assaults to police in fewer than one-third of all cases. Police make an arrest in just 5 percent of assaults, and fewer than 3 percent result in a felony conviction. Cases that do make it to trial—and result in a lifetime of punishment—represent only a small fraction of the perpetrators of sexual violence and, reflective of the legal system at large, disproportionately target Black men. In Illinois, roughly one out of every 139 men is on a public conviction registry—which include sex offenses, murder, gun convictions and crimes involving violence against youth. When accounting for race, the divide is even starker: one out of every 39 Black men in the state is on a registry.

Madeleine Behr, policy director at the Chicago Alliance Against Sexual Exploitation, says politicians have long weaponized survivors in order to appear “tough on crime,” all while pushing registries and increasingly restrictive policies that create more harm than they address. “Survivors and victims know who harmed them. It’s something that I think gets so lost in this conversation,” Behr told Bolts.

Studies have consistently shown housing restrictions and exclusion zones don’t make communities safer—and, in fact, can even weaken public safety. When the Minnesota Department of Corrections studied cases in which someone was reincarcerated for a new sex offense after being released from prison during a 16-year period, researchers couldn’t identify a single case in which residency restrictions would have prevented a new crime. A 2012 study from Connecticut’s Office of Policy and Management found that only 20 of the nearly 750 people released from prison in 2005 with sex offense convictions were convicted of a new sex offense. That’s in line with research from the Bureau of Justice Statistics that found people with prior sex offense convictions were far less likely than people convicted of other offenses to be rearrested or to go back to prison.

Even an Illinois task force created to study registration and residency requirements and composed of state lawmakers, law enforcement, policy advocates and state prison officials found that housing banishment laws were ineffective. In a 2017 report, the group said the homelessness and loss of family support caused by housing banishment policies put people at a higher risk of recidivism. “In sum, residency restrictions do not decrease sexual reoffending or the sex crime rates in the areas where they are used,” the task force concluded.

Patty Casey, a retired Chicago police commander who oversaw her department’s registration unit, calls the status quo a “lose-lose situation” for both police and people who have to register. Officers, she says, are tied up verifying the legality of place after place, while people with sex offenses are trapped in an endless loop of homelessness.

Casey singles out the restriction against living within 500 feet of home day cares as “absolutely ludicrous.” Home day cares can pop up practically anywhere—licenses are free and require little more than a background check, an inspection, 15 hours of training and a medical exam. “It creates a large number of homeless registrants,” Casey said. “They’re restricted [from living] almost everywhere.”

Casey told Bolts she plans to testify in support of the bill to ease residency restrictions and expand housing options during the upcoming legislative session. If signed into law, she said, “we would have so many less homeless persons, and it would be easier on law enforcement and easier on the registrants.”

It remains to be seen whether the support from folks like Casey and Lightford, the Senate majority leader, will be enough to muster the legislature to shirk decades of sensationalized, “tough-on-crime” policies. Four other legislators, including two more in Senate leadership, have signed on as bill sponsors and numerous others have committed to voting for it. While supporters expect some GOP opposition, a previous version of the bill even had a Republican sponsor in the House.

Notably absent from the conversation so far is Illinois Governor JB Pritzker, who is rumored to have presidential ambitions and has touted the state’s efforts to make Illinois a national leader in criminal legal reforms. Advocates with the Chicago 400 Alliance have questioned the governor’s silence on the issue. (Pritzker’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.)

“Why aren’t they telling the lawmakers they should pass this bill?” said Adele Nicholas, a civil rights attorney and director of Illinois Voices for Reform, one of the groups advocating for the bill. “I guarantee you that if they did, it would become law.” Nicholas has challenged numerous state sex offense policies in federal courts and before the Illinois Supreme Court, leading to three separate injunctions against the state.

The state’s “own commission looked at the evidence several years ago and concluded that these laws are counterproductive,” she said, referring to the 2017 task force. “The evidence is out there, but they’re not taking any action to stand up for evidence-based policy.”

Chicago 400 members have for months visited Springfield to educate legislators and build support for the bill. Steven says he’s confident they’ll ultimately prevail, but he’s often shocked by how little policymakers know about current law and its impacts on people with sex offense convictions. “You’ve made laws because people are uneducated; they’re afraid,” he said.

For the time being, hundreds of people with sex offense convictions continue to live in precarity, forced into homelessness by a system of the state’s design. “There really is no way of knowing the degree of punishment until you’ve lived it,” said Cheri, the mother of someone on the registry. “There’s no end. You just can’t ever get past it.”

Orr says he’s still trying to rebuild from the last time he went to prison because he couldn’t find a home. His sister died about a week before he was released in 2017. Orr remembers going to her home and finding the freezer brimming with containers of catfish, his favorite meal. “She was gonna throw me a surprise homecoming,” Orr said. “That was like another broken heart.”

The instability, fear and stigma lived day in and day out take a toll. “It can be so scary and shameful at the same time,” Orr said. “There’s so much politics in this particular crime. They break up a lot of families. A lot of people couldn’t survive this.”

“It’s very disappointing and hurtful,” he added. “I try to tell myself it’s gonna get better.”

Stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.