As Illinois Votes for Its Prosecutors, Defense Attorneys Say to Not “Just Go with the Flow”

We preview the 2020 races for prosecutor in the biggest Illinois counties, starting with the high-stakes election in Cook County (Chicago).

| December 12, 2019

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

The Political Report previews the 2020 races for state’s attorney in Illinois’s 21 biggest jurisdictions, starting with the high-stakes election in Cook County (Chicago).

When they launched their campaigns for prosecutor, the two Democrats running to replace the retiring Madison County state’s attorney both touted their experience working in his office as a core element of their appeal. “I was a prosecutor for almost 40 years, working in all departments through those years,” one said. “I have successfully prosecuted everything from traffic cases to murder cases” since starting “out in the office 15 years ago,” said the other. The sole GOP candidate in this southwestern Illinois county cites his background as a military prosecutor and assistant U.S. Attorney.

This is a frequent template for prosecutorial elections. Candidates compete over who has the longest or broadest experience prosecuting cases, glossing over the question of how they are prosecuting cases—and how their vast discretion shapes who is charged and with what severity.

But Junaid Afeef, running in populous Kane County, in the Chicago suburbs, instead put forth his work as a former public defender and civil rights attorney as a sign he would approach the job of state’s attorney differently.

“By having actually worked with the individuals who are brought into the system, usually people of color, you get to see the realities of the individuals that are fodder to the system,” he told the Political Report. “It provides you with a sense of perspective, compassion, that if you’ve never represented somebody like that you would never understand.” Asked how this affects how he views the prosecutor’s role, Afeef said it makes him want to “look upstream and say the reasons people engage in antisocial behavior has a lot to do with the trauma that they have experienced in their lives, and that trauma is the result, in many experiences of poverty and a broken system. If we want to create real reforms, we need to look upstream and address those problems.”

In neighboring DeKalb County, candidate Anna Wilhelmi told the Political Report that as a former public defender and defense attorney, she witnessed the criminal legal system’s racial patterns—it’s the “new Jim Crow,” she said—and that this primes her to not “just go with the flow” of how prosecution has conventionally looked.

“Why are we incarcerating all these people? The only reason is institutional racism,” Wilhelmi said. She faulted, for instance, the felony-status of many drug charges, an issue some states tackled this year.

Further north, in Lake County, candidate Eric Rinehart volunteered in his communication with the Political Report that he has never worked as a prosecutor. Asked how this would shape his approach to the prosecutor’s role, he said in a written message that it attunes him to “everyday failures.” “For many years, economic and racial characteristics have determined how victims and defendants are treated in the courthouse,” he said. “We have accepted this systemic failure for too long, and expected too little from our prosecutors when it comes to seeing the structural failures of the system.” He focused his comments on lower-level offenses specifically; he has also criticized his opponent, incumbent Michael Nerheim, for overcharging in a case in which five minors were charged with felony murder after their companion was killed by a homeowner during an alleged burglary.

Of course, having no prosecutorial background in no way guarantees that a candidate reforms the office, nor does such a background preclude changes. But in expanding what credentials are considered relevant for a state’s attorney, these candidates can at least fuel the conversation on what that office is for.

In 2019, a number of candidates with backgrounds as public defenders or defense attorneys won elections for prosecutor by running on platforms that emphasizes reform and decarceration, including Chesa Boudin in California, and Buta Biberaj, Parisa Dehghani-Tafti, and Jim Hingeley in Virginia.

Afeef, Rinehart, and Wilhelmi all said they were inspired by the recent nationwide wins by reform candidates. And Afeef and Wilhelmi both affirmed that they view reducing the incarceration rate as part of their platforms. None provided a specific metric of how much they would reduce prison admissions.

A neighboring example that may offer a useful pointer is Cook County (Chicago), where the number of people sentenced to jail or prison dropped by nearly by 20 percent in 2018 under State’s Attorney Kim Foxx, with a concurrent decline in the county’s crime rate. Cook County, which is home to more than 5 million people, also votes this year.

The largest of the three other counties is Lake, with more than 700,000 residents. Rinehart is running as a Democrat against Nerheim, the Republican incumbent. DeKalb will also come down to the general election; Wilhelmi, a Democrat, faces GOP State’s Attorney Rick Amato.

In Kane County, home to more than 500,000 people, Republican Joseph McMahon is retiring. The only GOP candidate is Robert Spence, a former prosecutor and judge who casts himself as a continuity candidate. The two Democrats running are Afeef and Jamie Mosser, who works as a prosecutor in the state’s attorney’s office and says she would set up new diversion opportunities for people with mental health or addiction issues.

—

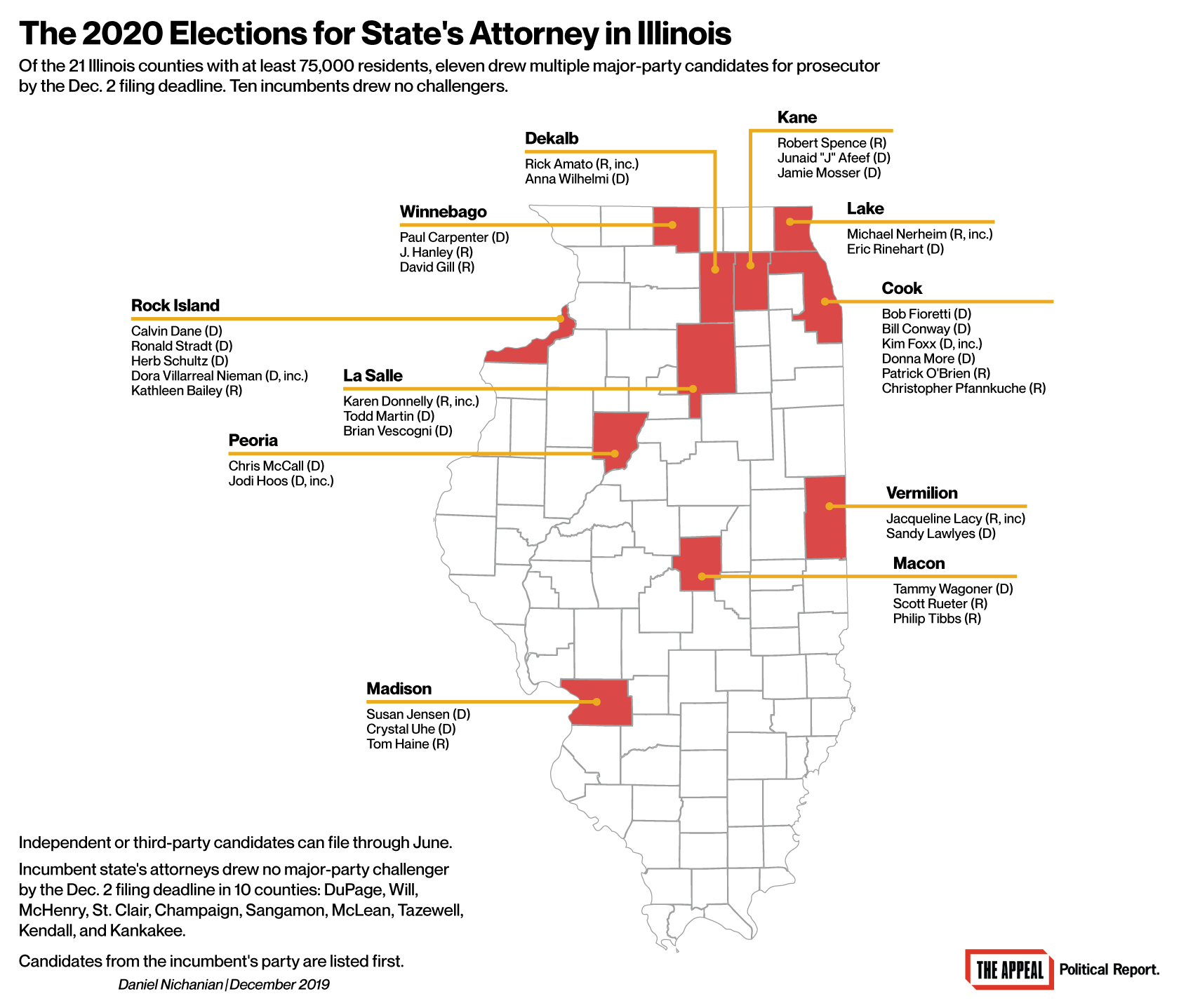

These are just a few of the 102 Illinois counties with prosecutorial elections in 2020. The filing deadline for candidates to run as a Democrat or Republican passed last week, and so I looked at the electoral landscape across the 21 counties with at least 75,000 residents.

A bare majority of these counties—11 of 21—drew more than one candidate.

Primary elections are on March 17, and the general election is on Nov. 3.

In the remaining ten counties, only the incumbent filed by the Dec. 2 major-party deadline. This most likely cuts short electoral debates about their record and policies before any campaign has gotten underway. Still, independent and third-party candidates can enter the race through June. DuPage, a Cook County neighbor, is the largest county with an unopposed incumbent; Bob Berlin, a Republican, has fought many criminal justice reforms during his tenure.

All candidates across these 21 counties can be found in our master list here. This map shows the candidates in the 11 contested elections:

Below are some additional preliminary stakes in these largest jurisdictions. The Political Report will return to many of these races in more details throughout 2020.

—

Kim Foxx faces re-election in Cook County: In 2016, after Chicago activists organized to protest Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez’s handling of Laquan McDonald’s shooting, Alvarez lost to Foxx. Foxx brought changes like diversion for drug possession writ large, and her policies encouraged fewer prison sentences. The Marshall Project found she has declined felony charges in more than 5,000 cases that her predecessor would have likely charged at that level.

A recent report by local organizations showed Foxx could do more to reform, for instance by ensuring that all prosecutors are following her less punitive guidelines. And yet, the three candidates challenging her in the Democratic primary have focused their messaging on attacking her perceived leniency.

Will Tanzman, executive director of The People’s Lobby, a progressive Chicago organization that has endorsed Foxx’s re-election bid, described his view on the race as defense against the “reaction” of “people who are invested in the racist system of police violence and mass incarceration” and are looking to “fight back against criminal justice reforms.”

In launching his bid, former alderperson Bob Fioretti built a broad “tough on crime” case off of Foxx’s highly-visible decision to not charge actor Jussie Smollett. Her “coddling of violent criminals, shoplifting felons, and campaign contributors show a jarring and unacceptable disrespect for victims, business owners, taxpayers and police officers,” he said. Another candidate, former prosecutor Donna More, assailed Foxx in a Chicago Tribune commentary for having “lax” sentence recommendations and for not being sufficiently aggressive against “repeat offenses. “Foxx seems to see herself as a reform politician,” she wrote.

Bill Conway, a former prosecutor, has done more to integrate talk of reform into his bid. He has said the problem with Smollett’s case is that some don’t access such outcomes. And he proposes diverting more people with addiction and mental health issues from incarceration. But Conway too depicts Chicago as a place where some people are not sufficiently punished, and he has built messaging around that picture of lawlessness. In an ad, he regrets that people who are arrested on gun charges are not staying in jail but are “back on the street by Monday afternoon.”

The Marshall Project’s article on declining in felony prosecutions found that gun charges are an exception, and Foxx herself has touted her office’s aggressive prosecution of gun offenses. This is all despite the limits of using incarceration and extended sentences to control gun violence.

—

Four open seats, seven challenged incumbents: Kane, Macon, Madison, and Winnebago are sure to have a new prosecutor since incumbents are not seeking re-election.

And incumbents face challengers in Cook, DeKalb, Lake, LaSalle, Peoria, Rock Island, and Vermillion counties.

Outside of the jurisdictions discussed above, the largest of these counties is Peoria, a county with some punitive practices where newly-appointed incumbent Jodi Hoos will face Chris McCall, a former prosecutor, in the Democratic primary. McCall cites his belief in criminal justice reform over “more of the status quo,” whereas Hoos has used a more conventional characterization of the office’s role. But McCall strongly qualifies his reforms as applying to nonviolent offenses. “I strongly believe that violent crime cannot be forgiven,” he said. Rinehart centered his platform on a similar distinction in his remarks to the Political Report. Advocates warn, though, that this is an overstated distinction and that changing approaches to all levels of crime is crucial to significantly reducing mass incarceration.

—

Judicial elections are under the spotlight, too: Cook County is also hosting a hotly-contested election for the Illinois Supreme Court, a body that is empowered to shape the rules that govern the state’s judiciary and criminal legal system. (This court’s members are elected by district.) Appointed in 2018, incumbent P. Scott Neville Jr. faces multiple challengers in the Democratic primary. At least one of them, Daniel Epstein, is running on using the court’s power to change the state’s prosecutorial and sentencing practices, such as the use of forensic science.

And that’s just one election. In Cook County alone, voters need to decide whether to retain dozens of judges in up-or-down retention elections. Last year, Matthew Coghlan became the first Chicago judge in 28 years to lose a retention election after a local coalition targeted him over his harsh sentencing record.

“This is the first sign of the new changes we plan on pushing through Chicago over the next decade,” Maria Hernandez, a Black Lives Matter Chicago organizer, told The Appeal at the time.