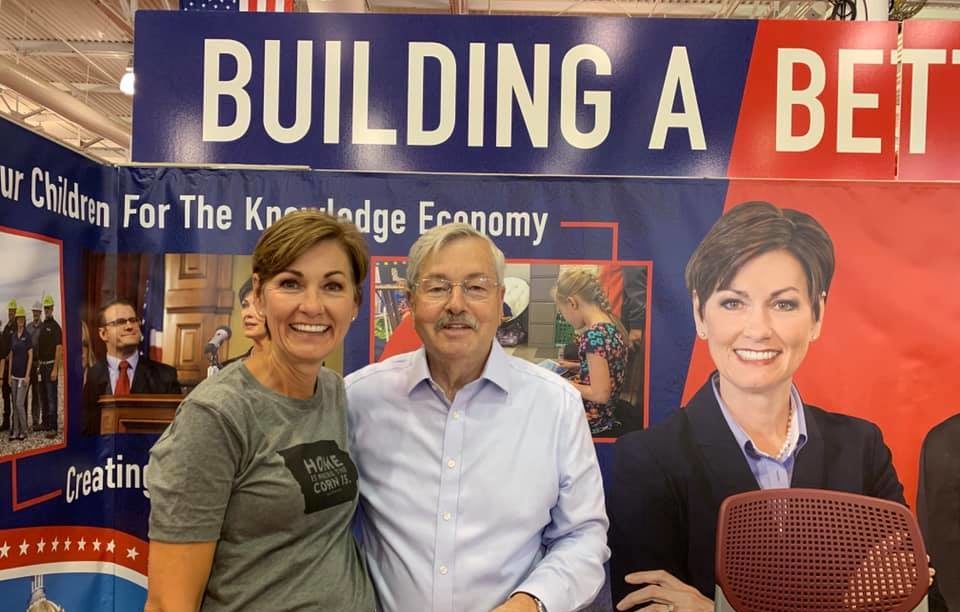

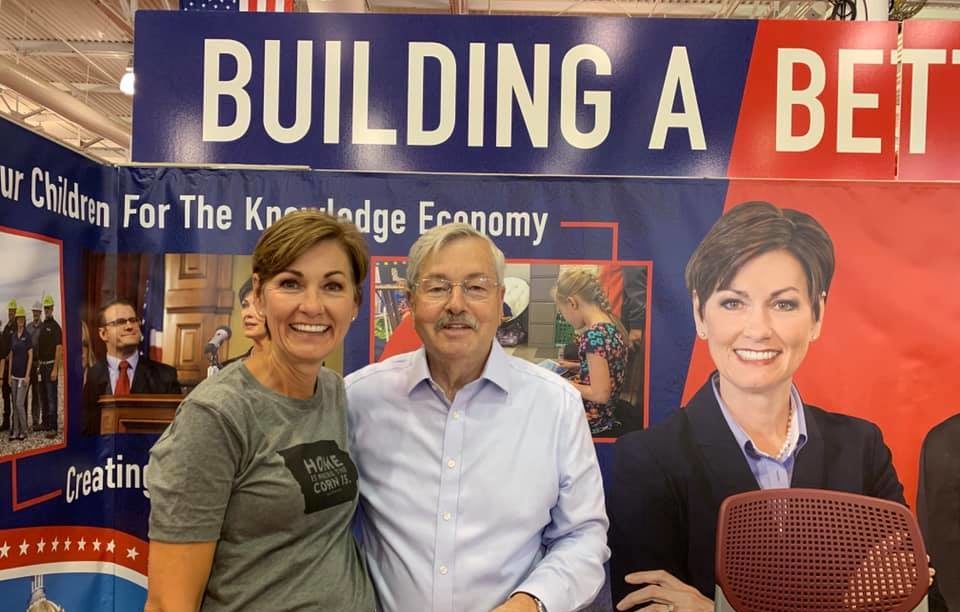

Iowa Governor Expands Voting Rights

Governor Kim Reynolds’ executive order restores the voting rights of tens of thousands of people. But it will also leave many Iowans disenfranchised, and little time remains before the November election.

Kira Lerner | August 5, 2020

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

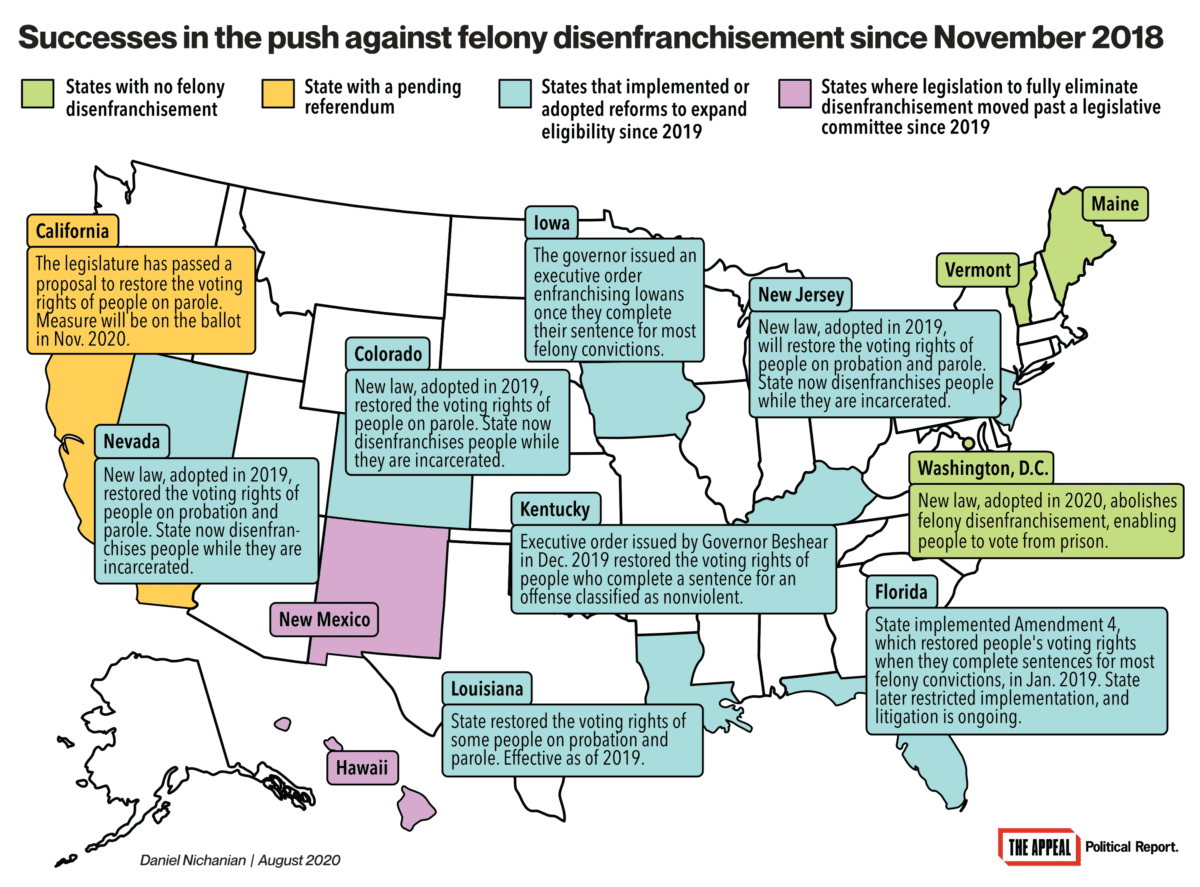

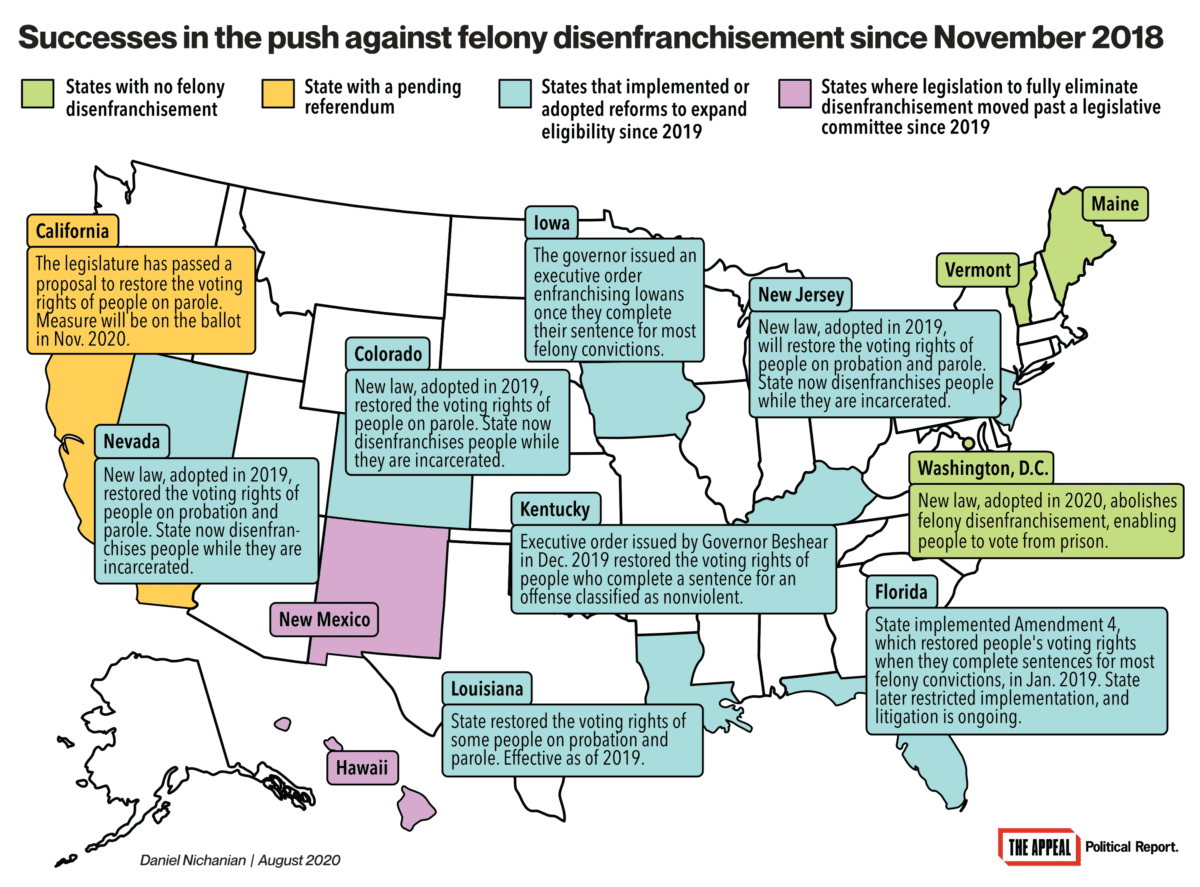

In the latest victory in the movement against criminal disenfranchisement, Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds issued an executive order Wednesday restoring voting rights to most people convicted of felonies who have completed their sentences. The order will enable tens of thousands of disenfranchised Iowans to register to vote by the November elections.

State advocates have long called for Iowa to expand voting rights. In recent months, Black Lives Matter activists protested in the state capitol, urging Reynolds to take action.

The order is a temporary fix since a future governor could rescind it. Reynolds has called on the legislature to adopt a constitutional amendment to expand voting rights, to no avail.

It is also a partial one. The order keeps people convicted of certain crimes disenfranchised for life, a practice the vast majority of states have ended, and it requires people to finish all terms of their sentence, including incarceration, probation and parole, before their rights can be restored.

“When someone serves their sentence and pays the price our justice system has set for their crimes, they should have their right to vote restored automatically,” Reynolds, a Republican, said in her announcement Wednesday.

Before Reynolds’s order, Iowa was the only state in the country that enforced a permanent voting ban on all people with felony convictions. (Other states have lifetime voting bans for people convicted of some, but not all, felonies and disenfranchise large numbers of people.)

The rule disproportionately impacted Black Iowans. Just 4 percent of Iowa’s population is Black, but Black people made up 13 percent of the state’s disenfranchised population in the 2016 presidential election, according to a report by the Sentencing Project.

Wednesday’s order also sets up a process for restoring voting rights to people who meet the requirements moving forward. But the order excludes those convicted under Iowa’s Chapter 707 homicide criminal code section, including manslaughter and voluntary manslaughter, or those with special lifetime sentences for sexual crimes.

Most states have ended all lifetime disenfranchisement rules, but some have exemptions. Reynolds’s carve-outs are considerably narrower than those implemented by Andy Beshear, the Democratic governor of Kentucky, who issued an otherwise comparable executive order in December. (Terry McAuliffe, Virginia’s former Democratic governor, had no carve-outs at all in the executive order he issued restoring people’s rights post-sentence in 2015.)

Other states have taken bolder steps to expand their electorate over the past year. Washington D.C. has abolished felony disenfranchisement altogether, including for people who are in prison, and Colorado, Nevada, and New Jersey have restored the voting rights of anyone who is not in prison, including if they are on probation and parole.

Still, Iowa drew special attention because of its exceptionally punitive statutes.

Previously, all Iowans with felony convictions had to petition for individual restoration from the governor. “That creates the potential for uneven justice,” Reynolds said Wednesday. Moving forward, only those convicted of the crimes excluded in the executive order — homicide, manslaughter, and sexual crimes — will be required to petition for their rights to be restored.

The executive order notably does not require people with felony convictions to pay off their restitution before they can vote.

A bill introduced by the Senate GOP last year would have required that people pay off those sometimes massive bills before regaining their rights. Rick Sattler, an Iowa resident who was ordered to pay $150,000 in restitution for a vehicular homicide, told The Appeal at the time that he would never be able to pay that off, meaning that even under that bill, he would effectively be disenfranchised for life.

In 2019, Florida Republicans adopted such requirements that voters pay off all fines and fees associated with their sentence before they can vote. This significantly shrunk the impact of Amendment 4, a constitutional amendment approved by Florida voters in 2018 that automatically restored voting rights to most people convicted of felonies. That law has been the subject of intense legal battles, and a federal appeals court will hear arguments over its constitutionality on Aug. 18, the same day as the state primary.

In signing the executive order, Reynolds noted that it is not a permanent solution, as a future governor could also change the state’s policy “with the stroke of a pen,” she said. To make the fix permanent, the state House and Senate would have to pass legislation to start the process toward amending the state constitution.

Reynolds’s predecessor, Republican Terry Branstad, did just that in 2011, when he rescinded Democratic Governor Tom Vilsack’s 2005 executive order restoring voting rights to roughly 80,000 Iowans. Advocates have urged Reynolds to reinstate Vilsack’s order for years.

Her order came just 3 months before the November presidential election and more than three years after Reynolds took office, leaving little time for advocates to reach out to newly-enfranchised voters, especially given the pandemic circumstances.

Just last week, Iowa’s county auditors called on Reynolds to act, arguing that the election is approaching and they would need time to put policies and procedures in place to give people with felony convictions the right to vote.