This Pennsylvania County Wiped Out Millions in Jail Debt

After Dauphin County ended the practice of charging people while they’re detained in jail, Commissioner Justin Douglas pushed it to forgive more than $65 million in lodging fees.

| January 15, 2025

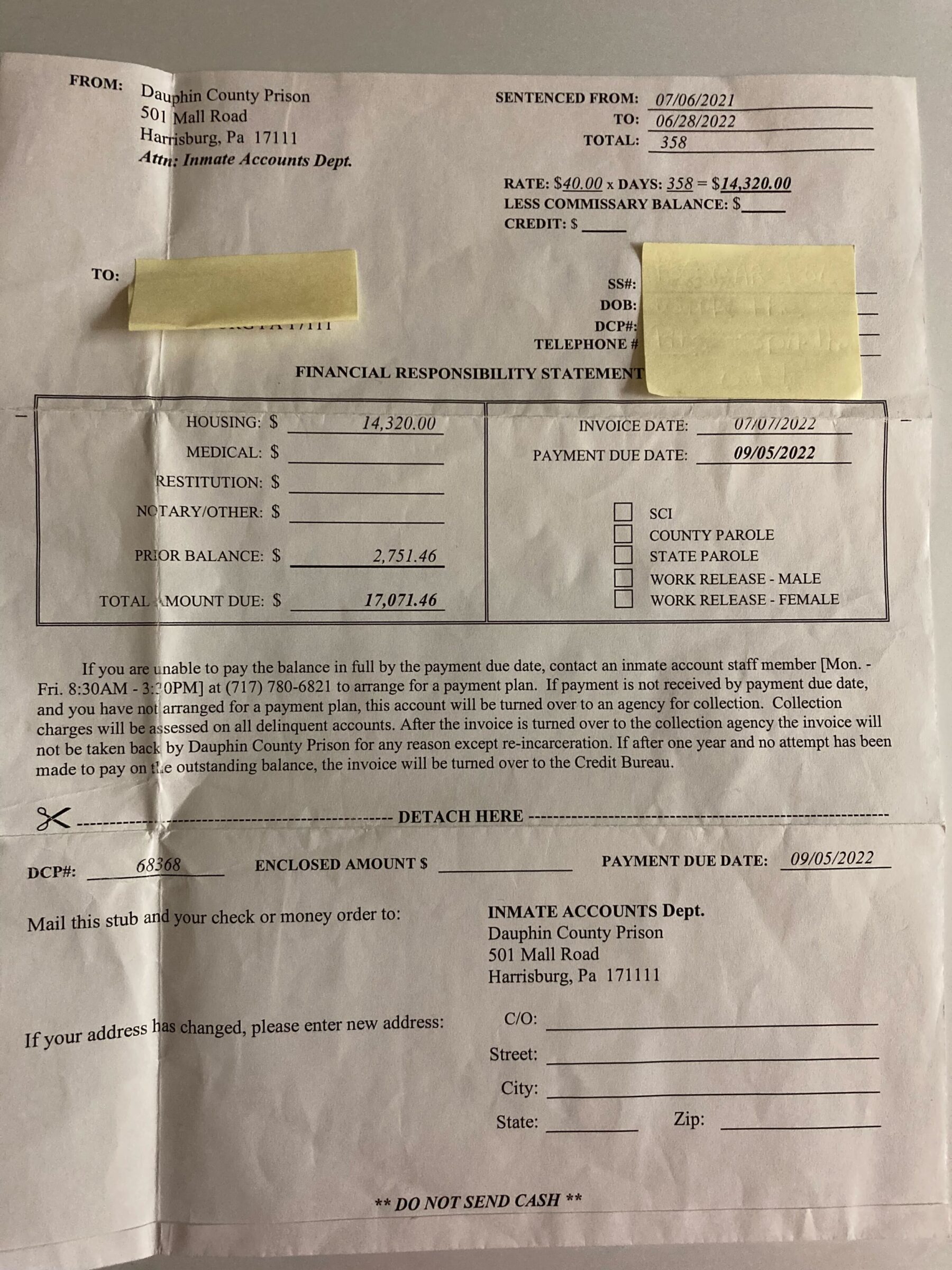

On July 7, 2022, days after Chad LaVia was freed from a year of incarceration at the jail in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, the county sent him a bill for $14,320 in “room and board” fees—$40 for each of the 358 days he’d spent inside. The invoice also reminded LaVia that he owed another $2,751.46 in fees from previous jail stints there, which brought his total debt to just over $17,000.

LaVia had only two months to pay off the debt, the invoice warned, until it would be turned over to a collection agency.

He didn’t have anything close to that amount of money, and even if he did, he was disinclined to pay because the demand seemed ridiculous; a jury had just found him not guilty of the charges that had landed him in the notoriously brutal Harrisburg jail to begin with. After all that time inside, it felt especially insulting for the county to hound him to pay for his own confinement even following his acquittal.

LaVia and his loved ones tried to put the debt out of their minds, but it hampered his chances at successful re-entry, his mother told Bolts recently. “It’s hard to be a productive member of society when you have $17,000 over your head,” Judi LaVia Jones, said. Her son is 50 years old and has long struggled with addiction and mental health issues, and can ill afford the additional burden of state-imposed debt, she added: “Try applying for an apartment with that. Try starting a business. It is always hanging over you.”

In September, Dauphin County’s commissioners voted to forgive the nearly $66 million in pay-to-stay debt looming over formerly incarcerated people and their families. The move, championed by a commissioner who won in 2023 after running on jail reform, followed a 2022 decision by the commission that ended pay-to-stay fees but had not erased people’s previous debts for jail stays.

LaVia Jones said the decision to finally forgive the outstanding jail debt will help her son move on with his life, calling it “a huge relief.”

“The longer you sat in jail, the more debt you incurred, the more debt your family incurred. People sit there pretrial for one year, two years. It’s so wrong,” she said. “So this really helps him to move on with his life.”

Local groups that advocate for incarcerated people in Harrisburg argued for years that the pay-to-stay scheme worked against efforts at successful re-entry for people released from jail, who are typically poor and who are almost always more concerned with basic survival and staying free than with settling debts.

Derrick Anderson of Harrisburg says that after he got out of jail a few years ago, the nearly $3,000 bill the county sent him for his stay seemed unreal and unworkable. “Even just $30 in my pocket felt like a lot,” he told Bolts. “It made the difference between me staying out here and me going back to prison. I could buy me something to eat, catch a bus, catch a cab. Something in my pocket. It makes a difference, and I’m telling you from experience. And they want to take it from you, and release guys with absolutely nothing.”

Lamont Jones, a Harrisburg City Council member who was formerly incarcerated, and who is running for mayor this year, was active in pushing for the county to erase people’s jail bills last year, saying such debts effectively work to encourage recidivism and degrade public safety. “In the scramble for survival, a lot of times, out of necessity, people will turn to a life of crime, not necessarily because they want to be a criminal. How can they figure out another way to pay?” he told Bolts.

Jones, who was released from incarceration in 2008, said it took him 15 years beyond then to pay off his debts to the system. He considers himself fortunate for not having succumbed to what he described as a financial “pressure cooker.”

“These fees, plus probation and parole constantly asking you for your supervision fee, plus the fines you owe, plus you may have child support, plus you need to feed yourself, clothe yourself—there just isn’t enough money in the pot,” Jones told Bolts. “And a lot of people, if they can’t find their way out of it, end up going back to the same thing that got them incarcerated in the first place.”

The jail-debt policy that Dauphin County finally ended last year is hardly unique. Such pay-to-stay schemes exist in some form in at least 43 states, according to Captive Money Lab, a research project of several universities that tracks economic punishment in the U.S. criminal legal system. The Associated Press reports pay-to-stay policies exist in many parts of Pennsylvania.

The practice of charging people for their time in lockup is but one contributor to a vast array of fines and fees that extracts money from people at virtually every stage of the criminal legal system—starting with jail booking and often lingering, through probation and parole, for years or decades after someone has been released, and affecting even those charged as children.

Cities, counties, and states try to collect such fees to fund government operations. But by reaching into the skinny accounts of incarcerated people and the family members who support them, these governments place vulnerable people in financial ruin while often failing to generate sustainable revenue streams.

In Pennsylvania, as in every other state, people dogged by fines and fees in the criminal legal system are disproportionately poor and non-white, a result of persistently classist and racist disparities in rates of arrest, prosecution, and incarceration. (The jail population in Dauphin County is majority-Black, even though the overall county populace is under 20 percent Black.) The fact that so many incarcerated people are poor ensures that pay-to-stay debts, and those for many other fines and fees, are unlikely to yield much return for the governments and collectors that call for them.

“It is unbelievably ineffective,” Dylan Hayre, national advocacy and campaigns director at the Fines and Fees Justice Center, told Bolts. “It’s one of those things where even surface-level scrutiny reveals the fact that this is not a smart thing to do.”

Justin Douglas, the Democratic commissioner who scored a shock upset win in 2023 on an uncommon platform of reforming the Dauphin County jail, and who championed the recent debt forgiveness, says that the county was spending about as much, if not more, on collecting those jail fees as it was taking in.

“This is fake debt to begin with, in that we’re never going to recoup $66 million, and it’s comical to think we would,” Douglas told Bolts.

Even those counties that put in serious effort to recoup criminal-legal debt can still struggle. Bucks County, Pennsylvania, outside of Philadelphia, spent the last four years carrying out a Delinquency Recovery Program that county leaders report has brought in less than 1 percent of the total debt owed there.

It was not any moral calling, but rather frustration over the county’s failure to recoup most jail fees, that first prompted Dauphin County to end pay-to-stay charges at the jail in 2022, when the commission moved to instead charge people a one-time booking fee.

To ensure it actually received money for the booking fee, the county started automatically taking $125 from everyone who entered the jail, at the moment of entry. For those who could not afford that fee upfront, the county would garnish funds that loved ones sent incarcerated people to buy marked-up commissary items and to make costly calls to family and friends on the outside.

The jail has been garnishing funds for other debts for years, pre-dating the booking fee. “If I got $100, they were taking $25. I had a $25 money order come in, they took half of it. You’re essentially being robbed,” Jerome Coleman, who’s been incarcerated multiple times in Harrisburg, and free since 2017, told Bolts. He now runs a small local business at which he employs other formerly incarcerated people.

Even as Dauphin County has now relieved all past pay-to-stay debt, it continues charging the $125 jail booking fee and continues to garnish funds to pay for it. Advocates hope the commissioners will abolish that system as a follow-up act to last year’s debt forgiveness, but they aren’t holding their breath.

Douglas, the commissioner who put debt forgiveness on the county’s agenda last year, said it has been difficult to bring about even modest reforms since his election. In the last year, for example, the county let incarcerated people go outdoors, briefly, for the first time in decades. The county is also putting out a bid for a new medical services contractor at the jail for the first time in almost 40 years, following repeated complaints against the current, longtime provider.

“This year,” Douglas said, “I’ve learned a lot about the lane I live in, and it has certain levers I can pull. I don’t set bail. I don’t determine the length of stay for somebody in jail. The fee is something that does fall under our purview. Building a coalition takes a long time, though.”

He added, “Dauphin County prison has some massive obstacles in front of it. We have earned our reputation, in a lot of ways.”

People formerly incarcerated in Harrisburg agree.

“It’s a shithole,” Anderson said.

Coleman remembered the food: “The meat they used to give us was green and pink.”

“When it got cold, there was ice inside my son’s cell,” LaVia Jones said.

Douglas flipped the board to Democratic control with his 2023 election, but that by no means signalled a progressive turn. Douglas said he finds he and his fellow commissioners have “different value systems” regarding the jail they oversee.

When the three-member board voted on forgiving the pay-to-stay debt, the other Democratic commissioner, George Hartwick, did not support the reform. It only passed, advocates told Bolts, because Douglas and a persistent outside advocacy campaign won over Republican Mike Pries, with whom Douglas is now forging an unusual power-sharing agreement.

In an email to Bolts, Pries said it was “an easy decision” to vote with Douglas on debt forgiveness because the debt was undercutting other county programs meant to reduce recidivism. “We were literally spending money on a good conceptual idea and goal,” Pries wrote, “but at the same time keeping individuals from reaching that goal by making it almost impossible to get credit, unable to get a mortgage, unable to rent an apartment, unable to get a car loan. That then becomes a cycle of despair and many times forces them to make decisions that put them right back where they started.”

Hartwick did not respond to an interview request or emailed questions from Bolts about the debt forgiveness and the booking fee.

Even though Pries described his vote in September as a no-brainer, Onah Ruth Ossai, an abolitionist organizer in Harrisburg, said she’s skeptical the issue would have come to a vote at all had Douglas not joined the board. “Having someone like Justin Douglas in office, at least we start to be able to shed a light on what’s happening. We felt completely in the dark before,” Ossai said.

She believes the booking fee must be the next target. Douglas told Bolts he “definitely” wants to abolish that fee, and that he’s planning a push, but that he does not believe he has support yet from his board colleagues to approve the change. That reform would be even more politically challenging than the debt forgiveness because the booking fee, unlike the pay-to-stay fee before it, actually does generate consistent revenue for the county, as a result of the garnishment policy.

In its most recent annual report, published in May, the county said it took in an average of 17 new detainees per day. That comes out to more than $2,000 extracted daily from people who, with rare exception, are detained pretrial—that is, still presumed innocent because they have not been convicted of the charges that landed them in jail. Cash bail amounts set by judges in the county ensures many are kept in the jail only because they cannot afford freedom.

In his email to Bolts, Pries said he’d be open to eliminating the booking fee, but only if the county comes up with a way to replace the money the fee generates. “If an alternative that does not negatively impact the county can be found, I will certainly consider that,” he wrote.

The organizers who sought the debt forgiveness say they will press now to end the booking fee and that they are encouraged by having an ally on the board in Douglas.

“What a light of hope this has been,” said LaVia Jones, Chad’s mother.

She told Bolts that she spent 27 years working in law enforcement in Pennsylvania, mainly investigating cases of alleged medical fraud. Since retiring and bearing witness to the financial exploitation and general suffering of her son and others in jail in Harrisburg, however, she has had a change of heart.

“I was always proud to say I worked in law enforcement,” she said. “When I got a true picture of what it’s like to be poor and to be incarcerated, I started to say to myself, ‘Boy, this criminal justice is not so just.’”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.