A Ballot Measure Targets Mail Voting in Maine

Question 1, on the November ballot, would set up a barrage of new restrictions on absentee ballots. This would considerably affect older voters and people with disabilities.

| August 27, 2025

Editor’s note (Nov. 4): Mainers rejected Question 1 at the polls on Nov. 4.

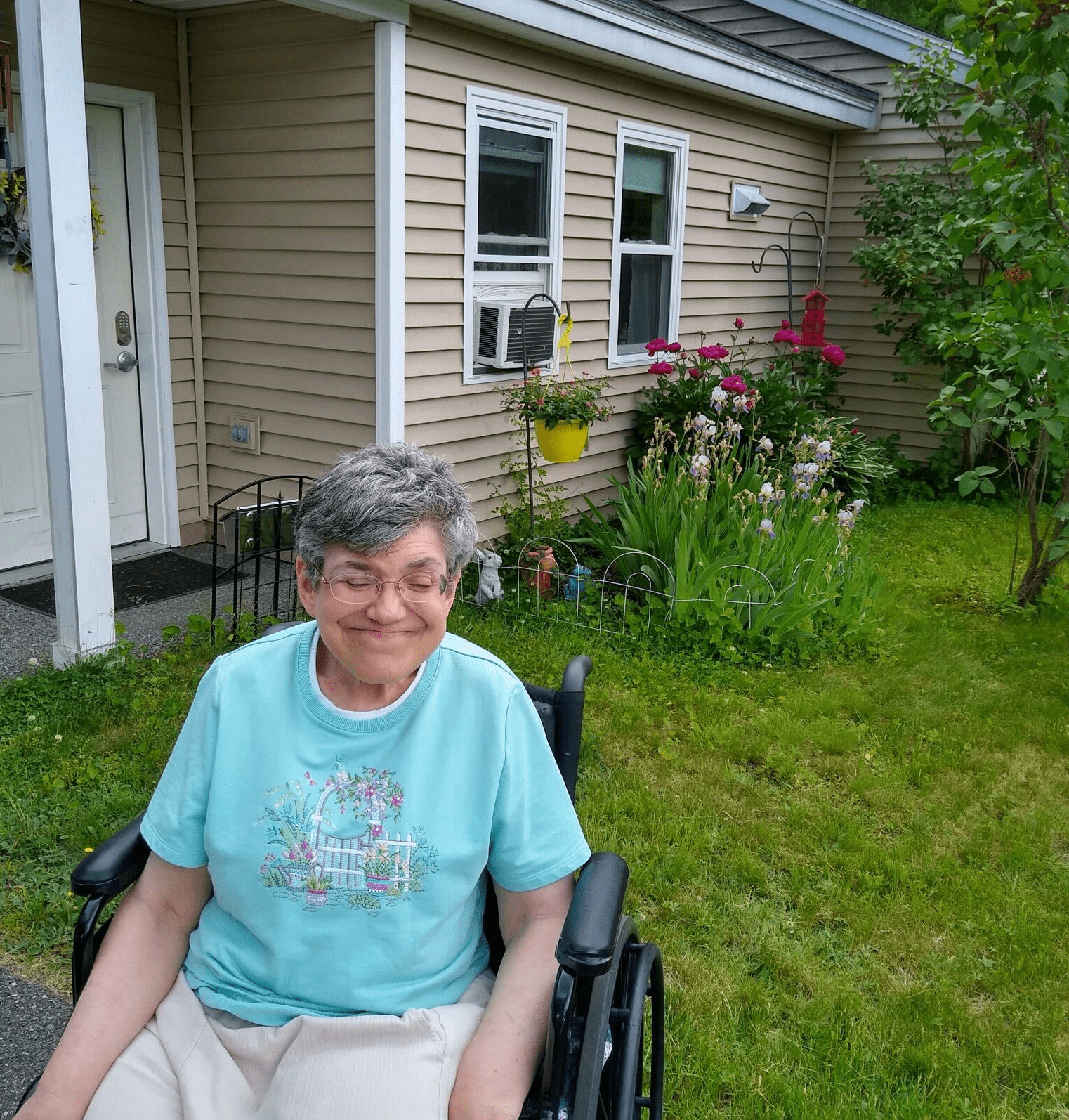

Sarah Trites, who is approaching her 60th birthday, has made a point to vote in every federal election since she turned 18. She worries her streak will end soon.

That’s because of Question 1, a conservative-backed ballot measure this November that proposes a series of barriers to voting, and particularly to voting by mail, in her home state of Maine. The measure would roll back key voter conveniences, forcing new burdens to ballot access on huge swaths of the state electorate.

Trites lives a 10-minute drive from her local elections office, an easy trip for some, but she is disabled and cannot drive a car, and there is no public transit in her town. That local office, she said, “might as well be miles away from me.” Her vision is also impaired, and so for years she has been requesting her mail ballots by phone—an accommodation that has helped her handle voting affairs from home.

Question 1 would repeal the option to request a mail ballot by phone, requiring all voters to visit an elections office in person or to submit an application, physically or online, in order to receive one. In another change, Question 1 would require all mail voters, of which there are many in Maine (nearly half of the state voted that way last fall), to repeat this process for each election.

“What a pain, to have to do that every single time,” Trites told Bolts. She says activities that might be easy for most—like traveling to an elections office, or applying for a ballot—are more complicated for people with disabilities.

These proposed new requirements figure to be especially relevant in Maine, where the average age is the highest of any state in the country, coinciding with a high incidence of disability.

“This would affect a lot of people,” Trites said. “People who cannot drive, who are physically unable to read for whatever reason.” She added, “I know people like that on both sides of the aisle, and this will be a big burden on all of us.”

Sixty-one percent of Mainers over 65 who voted in 2024 did so by mail, according to an analysis of state voting data by the Save Maine Absentee Voting Coalition, a group of 27 organizations in the state that oppose Question 1.

Want updates on the 2025 elections?

Sign up for our newsletter.

To help older folks and those with disabilities vote, Maine last year established a specific accommodation to allow anyone over 65 or with a disability to make a one-time request to receive a mail ballot without needing to ask again for all future elections. This policy, which the state calls “ongoing” absentee voting, would also be repealed by Question 1.

“We’re not even a voting rights advocacy organization, but we’ve had to become one,” Jess Maurer, executive director of the Maine Council on Aging, told Bolts.

Maurer is also concerned about other provisions of Question 1 that’d require all voters, including those voting by mail, to present a state-issued ID before casting a ballot. Maine does not currently require voters to show ID when voting.

National studies show that elderly voters and voters with disabilities are more likely than others to not have a state ID, in part because they may no longer keep an up-to-date driver’s license. Maurer says research shows Mainers very often stop driving altogether by the time they turn 80, and that a third of people in Maine over 65 have a disability.

“Ageism and ableism walk hand in hand,” she said of Question 1. “There will be people who, a year after this passes, if it passes, will go to vote and they won’t be able, and then they’ll be really mad. Or they’ll request an absentee ballot and get denied and not understand how they’re going to be able to vote.”

Question 1 comes as President Donald Trump renews his call to eliminate mail voting, and as many red states, including Utah and Kansas this year, have passed various measures to restrict the accessibility of mail voting. Trump earlier this month was open about his motives: If the country bans mail voting, he said, “you’re not gonna have many Democrats get elected. That’s bigger than anything having to do with redistricting.”

Question 1 follows this broad trend. It’s a citizen-initiated measure backed by a conservative PAC called The Dinner Table, which says its mission is to elect a Republican majority in the Maine House.

The PAC was co-founded four years ago by a Republican activist named Alex Titcomb, whose work is funded in part by Leonard Leo, the architect of the right-wing takeover of federal courts, and by Republican state Representative Laurel Libby, who was recently censured by her colleagues for doxing a transgender student and who has floated running for governor of Maine in 2026.

“My question to naysayers,” Libby said of Question 1, in an interview with Bolts, “would be: What’s the downside to ensuring our elections are as strong as they can possibly be and as secure as they can possibly be?”

Libby, who offered no evidence of fraud or misconduct to suggest Maine elections are insecure, said that “ongoing” mail voting—the service that allows Trites and others to automatically receive mail ballots each cycle—cannot be trusted.

“People move or they die, and this will ensure that only folks who have requested a ballot will receive a ballot and then vote in that election, rather than automatically sending ballots out when someone could no longer be at that address, for whatever reason,” she said.

The official campaign for Question 1, Voter ID for ME, has—as its name makes clear—emphasized the parts of the measure that specifically concern voter ID.

Voter ID laws, though proven to reduce turnout, are often popular with voters, and rarely fail when put on the ballot, though Arizonans rejected such a proposal in 2022. The most recent such measure, in Wisconsin in April, passed by about 25 points.

Opponents in Maine are concerned about the voter ID aspects of Question 1; besides the effects on older voters, the measure does not allow voters to use student IDs, even when they’re issued by a state university, or tribal IDs. But they tell Bolts they’re even more worried that voters will miss the fact that the measure contains so many other barriers.

In addition to forcing new burdens on how would-be mail voters can request ballots, Question 1 also proposes to limit towns and cities to one ballot dropbox apiece; to move the deadline to request a mail ballot from three business days before an election to seven; and to prohibit towns and cities from covering the cost of postage on mail ballots.

“Your voting rights are actually on the line,” said Jen Lancaster, spokesperson for the League of Women Voters of Maine. “This is far from just a very restrictive voter ID law; it will do so much more.”

Changes to absentee voting would affect not just older and disabled voters; overall, 43 percent of Mainers voted by mail in 2024.

If Question 1 passes, its changes would be implemented by the 2026 midterms, when Maine will elect a new governor and every seat in the state legislature will be up for election. Republican U.S. Senator Susan Collins is also up for election in 2026, in a race that could determine the balance of power in Congress.

For conservatives, Question 1 is the culmination of several years of work in the legislature to try to tighten voting rules. Republican Maine lawmakers, facing a Democratic trifecta in the state government, have failed repeatedly in recent years to enact new voter ID requirements.

By qualifying their measure for the ballot, proponents skirted that trifecta. They submitted 170,000 petition signatures, more than double the amount required—a strong statement, given Maine has only about one million adult residents. “In a small state like Maine, that’s pretty much a mandate,” Libby said. “Folks want to see voter ID as the law of the land.”

In an interview, Maine Secretary of State Shenna Bellows—a Democrat who opposes Question 1, is running for governor in 2026 and may end up facing Libby in a general election—told Bolts she hopes people will consider the entire measure, not just the voter ID angle.

“Question 1 is a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” she told Bolts. “Reasonable people can agree to disagree on the merits of voter ID. But if Maine voters understand everything that this measure will do, they will reject it.”

“Eliminating the convenience of absentee voting,” Bellows said, “would make it far more difficult for working people, seniors, and people with disabilities to participate in our elections.”

Bellows and other opponents of Question 1 have noted how it happens to come at a time when Maine is excelling at voter turnout, ranking second among all states in the 2022 midterms and fourth in last year’s presidential election. And officials are hopeful that the state can keep improving; the program allowing “ongoing” mail ballots for older and disabled voters, so they don’t have to request a new one each cycle, only went into effect in February 2024.

Sarah Trites thinks this has been a critical change. “I was having to call up every single time and request a ballot,” she said. “That was becoming very difficult to do, to have to remember when every election is and to make a call every single time. To have it sent automatically has been great, but now that could go away.”

Question 1’s proponents have downplayed the changes to mail voting while professing outrage at the wording of the measure, which Bellows approved: The official language that voters will see on their ballots notes five different policy changes proposed by Question 1 before mentioning voter ID, the issue that proponents think should lead the description of the measure.

Titcomb, the co-founder of The Dinner Table, has called this ballot language “a partisan editorial” from Bellows. The Voter ID for ME campaign argues that the secretary should have approved a ballot measure that specified the voter ID aspect and referred to everything else simply as “other changes.”

Bellows defended the ballot language as faithful to the measure, and said that it’s important for voters to understand Question 1 completely.

Maurer, of the Maine Council on Aging, said she fears the November outcome if the electorate misunderstands the measure as being strictly about voter ID.

“We have to make this real for people,” she said, “and we don’t have much time.”

That article has been corrected on Sept. 3 to reflect that Question 1 would allow Mainers to request mail ballots online; an earlier version misstated the options to request a ballot under the measure.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.