“A Betrayal in Slow Motion”: Maryland Democrats Forgo Banning ICE Contracts

Maryland’s GOP sheriffs are rushing to join the 287(g) program and expand ICE’s reach, and a push to halt them failed in the Senate. Democrats said they worry about Trump’s threats.

| April 24, 2025

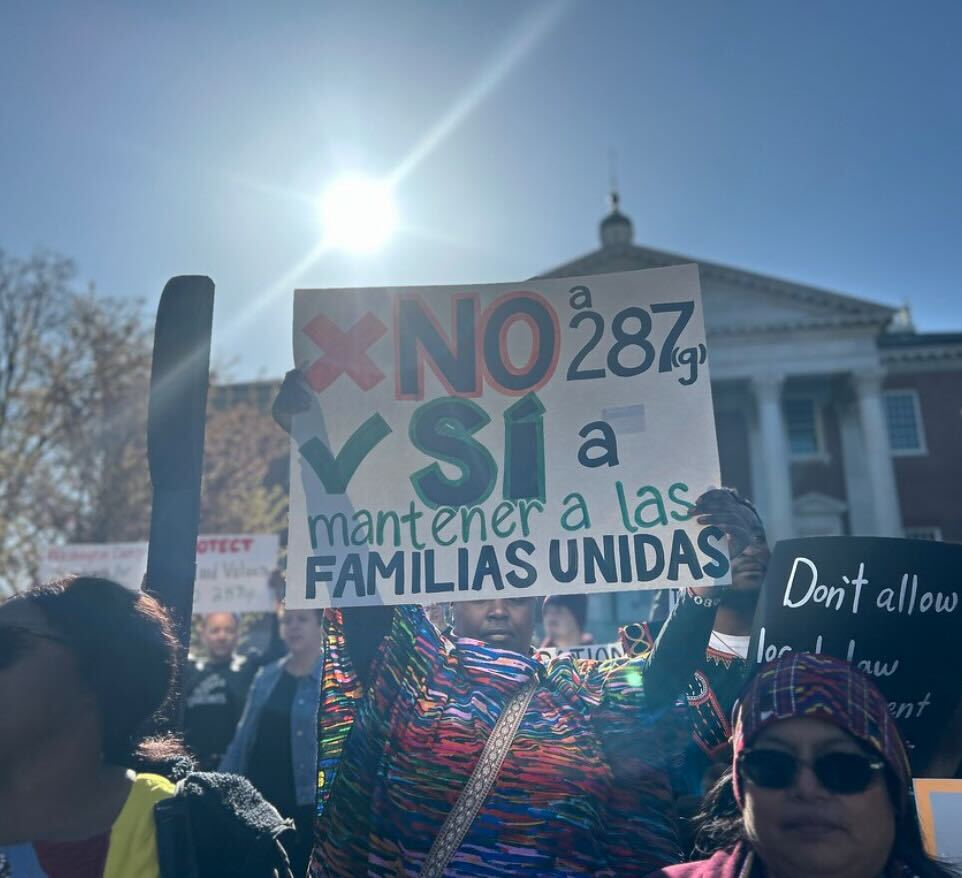

The clock neared midnight on Monday, April 7, the final day of Maryland’s 2025 legislative session, and immigrant rights advocates, who’d been at the statehouse all day, and for many long recent days before this one, held fading hope that their top priority would yet pass.

They were pushing the legislature, with its Democratic supermajorities, to ban Maryland sheriffs from participating in the federal 287(g) program, which empowers local law enforcement to arrest and detain people they suspect are undocumented on behalf of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The program has drawn in conservative sheriffs nationwide who are eager to assist ICE. Several blue states have already banned it, but Maryland has not.

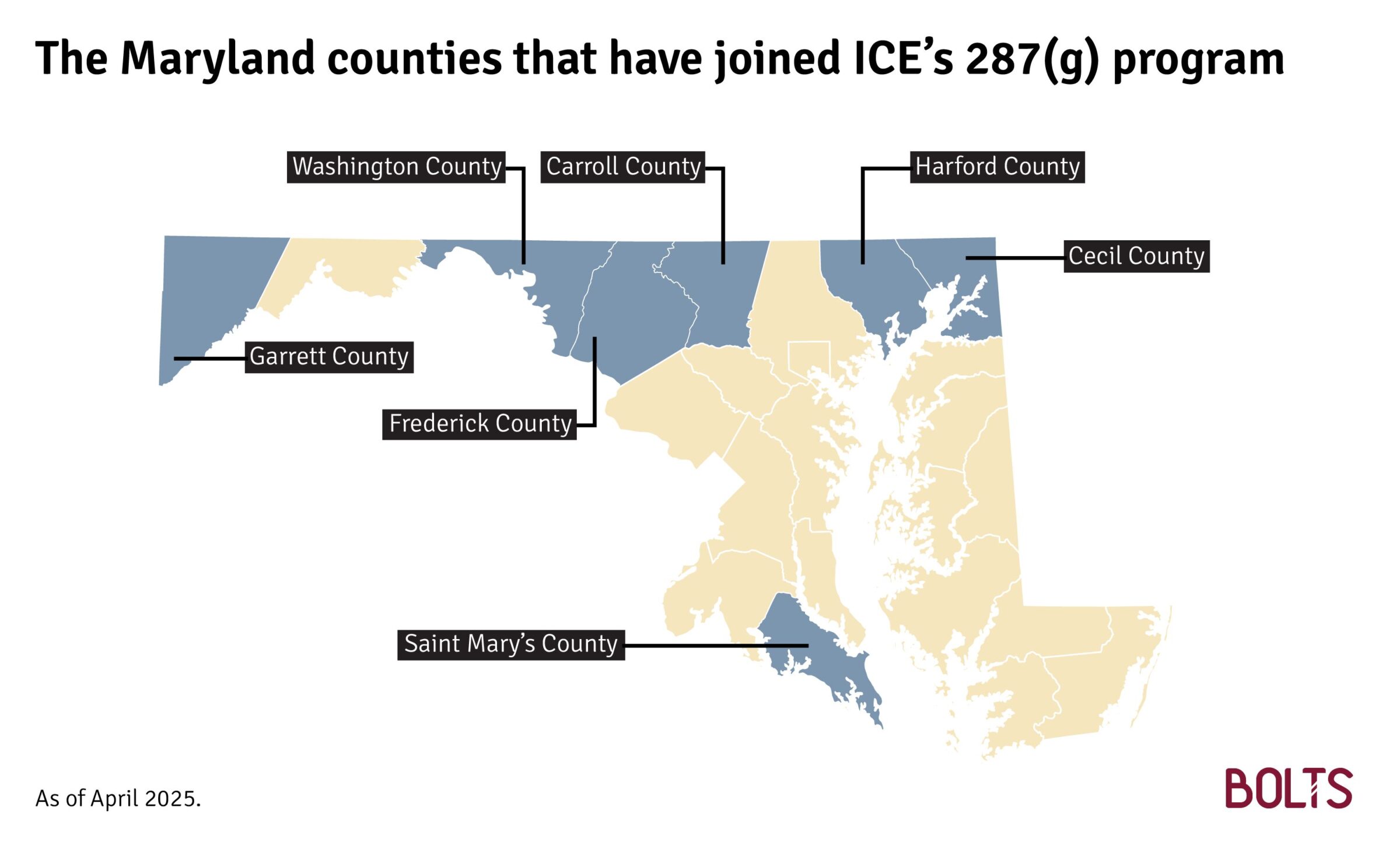

In fact, amid President Trump’s return to office on a promise to deport millions, Maryland’s Republican sheriffs have rushed to join the 287(g) program: Four of the state’s 24 sheriffs have contracted into it just in the last eight weeks, bringing the total state participants to seven. More than 1.1 million Marylanders, nearly a fifth of the state, now live in 287(g) counties.

Immigrant rights advocates urged Maryland’s Democratic lawmakers to respond with equivalent swiftness and halt those contracts. The 287(g) program “is the most clear, direct funnel into the deportation machine,” Cathryn Jackson, public policy director of the immigrants’ rights group CASA, told Bolts. “It boils down to whether we want to help Trump right now, or help stop him.” Her plea proved successful at first: The Maryland House passed a ban on 287(g) in March through House Bill 1222. But the Senate then let the bill languish for weeks, amid negotiations and opposing pressure campaigns.

In the final hour of the session, it became official: There would be no 287(g) ban this year in Maryland. The Senate gutted HB 1222 at 11:38 p.m., removing the ban on 287(g) contracts and replacing it with less ambitious protections to limit ICE access to public facilities and to immigrants’ personal data. The House adopted the amended bill at 11:56 p.m.

At midnight, to mark the end of the session, balloons and confetti in black, yellow, and red—Maryland state colors—rained down on lawmakers. Taking in this scene from the public gallery were a few dozen devastated immigrant rights advocates, many of whom have been agitating for a 287(g) ban for years, and many of whom are themselves immigrants vulnerable, either personally or by extension of family members, to ICE. They supported the protections that did pass, but saw them as poor consolation.

“Legislators are a little drunk on the floor, playing with balloons,” recalled Jackson. “And this big group of immigrants are stunned and silent. They’re crying. … It felt like an abandonment.”

It was the culmination of a session that Jackson characterized as “a betrayal in slow motion.”

Two days later, the state Republican Party cheered Democratic lawmakers’ killing of the 287(g) ban: “MAJOR WIN,” the party posted on X.

This was at least the third year since 2020 that a proposed 287(g) ban had failed to pass Maryland’s legislature, but this one particularly stung supporters, because lawmakers knew well before the session began that Trump was looking to reinforce the cooperation between local law enforcement and ICE.

And the debate within Maryland grew more heated in the the final weeks of the session, as a Maryland resident, Kilmar Abrego Garcia, involuntarily became an international symbol after he was deported to a Salvadoran mega-prison despite having a legal order protecting him from removal.

Trump’s Department of Justice has confessed this was an “error” but has refused to try to correct itself. On the final day of Maryland’s session, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ordered the Trump administration to “facilitate” the return of Abrego Garcia, but the administration has continued to defy that order. Lawmakers told Bolts they were tracking the case at the same time they were holding last-minute talks on 287(g).

“I think what happened with the kidnapping kind of heightened things,” said state Senator Karen Lewis Young, a Democrat who represents Frederick County, a 287(g) jurisdiction, in reference to Abrego Garcia’s case. She told Bolts that she supported the proposed ban. “I think if that had happened earlier in session, the 287(g) bill might have moved, because I think it gave everybody a much more realistic awareness of how dangerous that program can be.”

Abrego Garcia is not imprisoned today because of 287(g); he was arrested, in fact, in a county that does not participate in the program. But, advocates say, the lack of due process in his case is very familiar to those detained under 287(g): “The heart of 287(g) is to undermine due process,” said Jackson, the CASA policy director. “People come in, get charged with whatever they get charged with, and they get deported without ever seeing a judge, without making their case.”

The 287(g) program can take various forms, but, as of now, the Maryland counties that have joined it are using a version that only takes effect within county jails: Once someone is booked in a participating Maryland jail for any reason, including a minor offense such as a traffic violation, sheriff’s deputies have the authority to interrogate them and research their status, and to keep detaining them on immigration grounds unrelated to their initial arrest.

Stephanie Wolf, director of immigration services for Maryland’s state public defender office, said 287(g) agreements can “turn the criminal legal system into a big scoop for easy, convenient ICE arrests.”

“As ICE tries to boost its numbers, as it tries to meet the pressure to produce more and more arrests, they’re going to use that tool aggressively,” she told Bolts.

The Trump administration in February revived another version of 287(g), known as the “task force” model, which empowers local officers to conduct immigration enforcement in the course of everyday policing, like during a traffic stop, before the point of jail booking. No Maryland county has yet joined the “task force” program.

The expansion of local-federal immigration enforcement sends a dangerous signal, said Neill Franklin, a retired Maryland State Police major. “If you’re in the immigrant community, if you’re not documented, if you’re working and you’re trying to support your family and now you hear about this, now you are really going to be less likely to interact with the police if need be, be it as a victim or a witness,” said Franklin, who spent decades working on criminal investigations in the state and who testified in favor of the 287(g) ban in February. “It isn’t difficult for people to understand now, ‘I could be next.’”

While three populous blue states—California, Illinois, and New Jersey—have banned their counties from joining 287(g), Maryland Democrats are leaving the program to the discretion of local sheriffs.

The sheriffs of Carroll, Garrett, St. Mary’s, and Washington counties have all signed contracts with ICE since Feb. 28. They joined the sheriffs in Cecil, Harford, and Frederick counties.

All seven of these sheriffs are Republicans, and all but one of them represent very conservative counties.

Frederick County, the most populous of the seven with nearly 300,000 residents, stands out as Maryland’s only 287(g) county that voted against Trump in November. Its sheriff, Chuck Jenkins, is a longtime ally of Trump’s team—an “American patriot,” says Tom Homan, the former ICE administrator who is helping lead Trump’s efforts this year. According to a legal brief by the ACLU of Maryland, Jenkins once claimed that “the immigration problem” was the nation’s “single biggest threat,” declaring a mission to “shoot them [immigrants] right back out of Frederick County.”

Jenkins’ stance on immigration was a focal point in his last contested, successful re-election bid, in 2022. All Maryland sheriffs are up for election in 2026.

Jenkins opposed the legislature’s proposed ban this spring: “The passing of this legislation and termination of these immigration enforcement agreements will only serve to make our streets more dangerous, embolden violent criminals, and place our families at greater risk of being a crime victim,” he wrote in a letter to lawmakers.

In a letter of his own, Washington County Sheriff Brian Albert wrote, “If this bill is passed and I am required to release a known criminal back into my community and they kill or injury (sic) a member of the public, the community will not be asking questions of the senators or delegates here in Annapolis the will asking (sic) me the local sheriff.”

These and other sheriffs were echoing ICE’s arguments that so-called sanctuary policies are a threat to public safety, and that 287(g) is an important tool to apprehend immigrants who are committing crimes. Evidence shows that immigrants in the U.S. commit crimes at lower rates than U.S.-born citizens do.

Plus, people who are detained due to the 287(g) program are typically not yet convicted of a crime; they’re likely to have been booked in jail before any trial. According to data compiled by the state’s public defender’s office, from 2016 to 2023 in Maryland, 445 of the 771 people detained under 287(g) had been convicted of no crime at all. Most of the rest had been convicted of minor misdemeanors—that is, the least serious crimes.

Several lawmakers who talked to Bolts since the session ended pinned the failure of the 287(g) ban primarily on a general fear that the Trump White House could seek to punish Maryland if it passed the ban—that is, make life even harder on immigrants in the state than it is today, as retribution for anti-287(g) reform.

State Senator Will Smith, a Democrat who chairs a committee that reviewed immigration bills this session, said that while he supported the ban, “I’m also clear-eyed as to the likely retaliatory actions that would be forthcoming from the administration if we were to do so.”

“Do you venture in and live your values, with the understanding that repercussions could hurt thousands or hundreds of thousands of Marylanders?” Smith continued. “It’s a terrible and unfortunate intersection to be at as a lawmaker.”

Smith’s committee advanced the 287(g) ban to the Senate floor. Smith then helped broker the final-hour plan to pass limited immigrant protections without the 287(g) ban.

The most powerful figure in Smith’s chamber, Senate President Bill Ferguson, has mirrored Smith’s comments, telling WYPR radio days before the session ended, “All of us in Maryland look towards our immigrant communities and understand how much pain and suffering is being felt and fear, and we have to recognize the very true reality that there are consequences that have been issued from the federal government about what happens with states that do not comply with certain immigration orders.

“So this is the value judgment that we are trying to navigate through,” added Ferguson, who did not respond to a request for an interview from Bolts.

In recent months, the Trump administration has targeted the states that have banned local cooperation with ICE, including by suing Illinois and New Jersey, and by investigating the governor and attorney general of New Jersey.

Democratic leaders in those states have embraced the fight: “We’re not in the immigration business,” New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy said this month. Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker vowed at the onset of this presidency to “stand in the way” of the mass deportation program.

Maryland’s Democratic governor, Wes Moore, did not respond to a request for comment from Bolts.

House Delegate David Moon, a Democrat who voted for HB 1222 back when it contained the 287(g) ban, said the House knew that the Senate would want to move cautiously, which is why the House watered down its own legislation early in the session to try to facilitate its passage: Besides banning the 287(g) program, the House version of HB 1222 would have required local jails to notify ICE before releasing people already convicted of felonies and certain other offenses. (Maryland experts said most counties are already doing this, though some have adopted measures to limit interaction with ICE.)

“We pre-compromised on coordinating for convicted felons, violent criminals, so we could get this thing moving,” Moon said. “We had gotten a bad feeling at the start of session that we weren’t going to have alignment to just straight-up repeal the 287(g) agreements.”

The final version of HB 1222—the one lawmakers adopted minutes before midnight on April 7—did not contain this requirement, nor the ban on 287(g). Instead, it empowered certain “sensitive-location” public facilities, including libraries, state hospitals, and public schools, to deny warrantless entry by ICE agents. Lawmakers hope this will help preserve access to basic government services for people who might otherwise avoid those services out of fear of ICE contact.

It also included a “data privacy” reform meant to prohibit state agencies from handing ICE personal identifying information about immigrants living in the state. Like the “sensitive-location” measure, this is also meant to reassure immigrants that they can access public services without fear of ICE referral.

Those changes are important, said Jordy Diaz, an immigrant rights activist close to many people vulnerable to deportation. But, he continued, they’re not what the immigrant community mainly needed from the legislature this year.

Diaz, who resides in liberal Montgomery County, has friends who live in parts of the state that are covered by 287(g) agreements. He said that people he knows have long hesitated to spend much time in those areas, and that they’ve completely stopped doing so since Trump retook office.

“We’re just scared of that interaction, of what might be asked,” Diaz, who is a citizen, told Bolts.

Like others interviewed for this story, he said he does not view a ban on 287(g) as a cure-all for those living in the kind of fear that’s lately taken over his circles. But, he said, the ban would have represented a meaningful severance of formal cooperation between Maryland counties and ICE, and it would have meant that thousands of Marylanders would be less likely to enter the deportation pipeline in coming years.

Senate leaders’ argument that passing the ban might not have been worth angering the White House rings hollow to Diaz, seeing as ICE is clearly on a warpath whether or not Maryland takes up a reform. “Look at what’s happening across the country,” he said.

“I’m very disappointed,” Diaz added. “We feel like right now is when we need Democrats and those in leadership to really stand up for us, like they’ve said they’d do for so long. They really dropped the ball.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.