With 17 Candidates and Unusual Voting Rules, Memphis Mayoral Race Gets Jumbled

Memphis is a rare city to hold its elections in just one round, however low the winner’s share—an anomaly that’s decades in the making, from a court ruling enforcing racial equity to GOP preemption.

| September 29, 2023

Editor’s note (Oct. 5): Paul Young was elected mayor of Memphis on Oct. 5, receiving 28 percent of the vote in this 17-candidate field in the city’s first and only round of voting.

Memphis residents who head to the polls next week will face a dizzying ballot for mayor. With Mayor Jim Strickland term limited in this city of 600,000, there are 17 candidates running to replace him in this nonpartisan race—a crush of local businessmen and politicians, including a former reality TV judge, two different life coaches, and a former mayor. Despite the crowded field, Oct. 5 will be the only round of voting: Whoever finishes first becomes the next mayor of Memphis, however small their share of the vote.

Memphis is by far the most populous city in the nation to elect its mayor this way, in a one-round, first-past-the-post election. There is no primary, no runoff, no ranked-choice voting to cull the herd, encourage consolidation, or help clarify the stakes. All other U.S. cities with at least half a million residents have some such mechanism to ensure that the field narrows, or that the winner gets broader support.

This rare voting procedure was set up when a court eliminated runoffs more than 30 years ago to prevent white residents from coalescing to block Black candidates. But the white share of the population has declined considerably since then, rendering that original purpose more obsolete. Voters in this now majority-Black city tried in recent years to change their election rules and adopt ranked-choice voting, a system that could produce winners with wider appeal. But Tennessee Republicans who run the state government adopted a law in 2022 that banned the use of ranked-choice in the state.

This has left Memphis with a system that risks diluting voters’ power, making it harder for them to elect leaders who represent the preferences and priorities of a large share of the population.

“There’s still a whole lot of battle fatigue, angst, frustration, anxiety,” says Reverend Earle Fisher, director of the Black Clergy Collective of Memphis, about voters’ mood. “If there’s one thing I’ve heard a million times over the last few months that I wish I had a nickel for every time I heard it is: ‘There’s too many people in this race.’”

He says the danger to democracy is that public officials are getting elected without a mandate, without “50 percent of the people participating saying, ‘I want this person because I believe this person is gonna do the things that the majority of us want to be done.’”

Whoever wins the mayor’s race in Memphis will have to contend with concerns over public safety and economic disinvestment, a shrinking population, and a GOP-run state government that has increasingly interfered in the decisions made by its cities. The election also comes in the wake of Tyre Nichols’ death and other high-profile police shootings that have rocked the city recently, which puts a spotlight on the next mayor’s relationship with the police department and appointments of a police chief.

But in a field that’s this crowded, and where nearly all mayoral contenders say they share the same broad priorities—reduce crime, promote economic investment, and improve housing—it’s been exceedingly difficult for the conversations to go beyond sound bites or to really air out any policy disagreements between any two candidates.

“Voters don’t really create their own messages. They choose between the alternatives that are put in front of them,” says Jack Santucci, who studies electoral systems as a political science lecturer at Queens College, CUNY. “Especially in a nonpartisan local election, voters are going to have trouble differentiating among the candidates.”

Local media has made decisions about which of these 17 candidates to invite to debates based on how much money they’ve raised and the available polling.

By those metrics, the leading candidates include Shelby County Sheriff Floyd Bonner, who is touting support from police unions and his long experience in law enforcement, while also drawing criticism for the high number of deaths in the local jail he oversees. They also include Paul Young, president of the Downtown Memphis Commission, a newcomer to electoral politics who leads the race in funds raised; state Representative Karen Camper, who voted against the law to ban ranked-choice voting while in the legislature; and Shelby County Commissioner Van Turner, a former Memphis NAACP president whose left-leaning platform has earned him the endorsement of Justin Pearson, a lawmaker representing part of the city who was expelled from the state House (and later reinstated) by Republicans earlier this year over a protest for gun control.

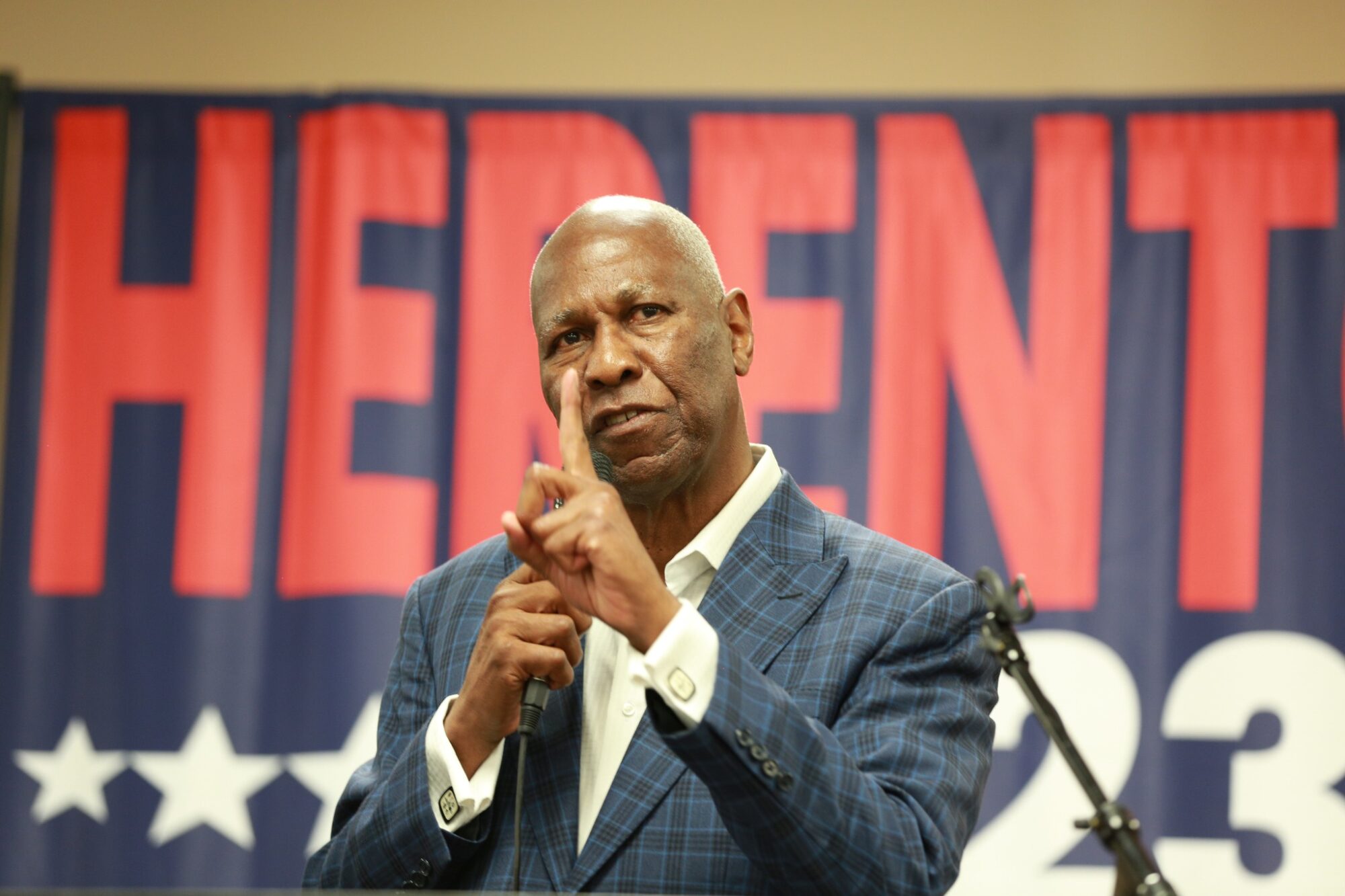

Also running is Willie Herenton, who has made fewer appearances at public events, skipped debates, and raised a lot less money. But as the former mayor from 1992 to 2009, the name recognition he garnered over his five terms makes him a frontrunner: In an August poll conducted by Emerson College, Herenton received 16 percent—enough to put him in the lead. A plurality of respondents, 26 percent, remained undecided.

Even in smaller debates organized by the media, candidates have had limited time to state their cases and have struggled to distinguish themselves. The dynamic has heightened competition, incentivizing attack ads and even jockeying among the candidates over who has the best Christian faith credentials.

Every possible advantage counts: The next mayor is likely to win with less than 30 percent of the vote, if not less, hardly a mandate from voters to carry out a particular policy vision.

“What we’re facing right now, with so many candidates in the way, is that we could possibly have the next mayor of Memphis elected by 20,000 or fewer votes,” Martavius Jones, chair of the city council, told Bolts.

Tennessee’s other largest city just held its own mayoral race this summer under different rules: Nashville holds runoffs for its local elections, giving the race a much different shape.

There were 12 candidates for mayor during Nashville’s first round of voting on Aug. 3, and the top two vote-getters, Freddie O’Connell and Alice Rolli, received 27 and 20 percent of the vote, respectively. In Memphis, this would have been the end of the road, but in Nashville it paved the way for a 6-week runoff campaign. O’Connell touted his progressive bona fides while Rolli ran with conservative support, a contrast that gave voters a clear choice. During the runoff, O’Connell rallied support from progressive advocacy groups, labor unions, as well as several of the candidates he beat in the first round, and on Sept. 14, won the mayorship with a decisive 64 percent of the vote.

Republicans in the legislature floated a bill earlier this year to ban runoffs in municipal elections throughout the state. Democrats denounced it as an attempted power-grab in the run-up to Nashville’s election, warning that it would allow a single Republican to beat out a crowd of Democrats in the decidedly blue city. Had the bill passed, the summer’s result would not have changed since O’Connell won both rounds. Still, Rolli, the sole Republican among the major candidates, would have been 7 percentage points from victory rather than the 28 percentage points by which she lost the runoff.

Memphis too used to have runoff elections for its mayoral and city council contest, a system it adopted in the mid 1960s. Because of the city’s racial makeup at the time—63 percent white and 37 percent Black—runoffs worked to preserve white political power and ensured that Black candidates almost never took office. Runoffs were used not only to consolidate votes around just a couple of candidates, but also to shore up racial voting blocs.

“Blacks could not hope to win citywide races given the traditional level of white polarization and bloc voting,” explains Marcus Pohlmann in his book Racial Politics At a Crossroads, a history of Memphis electoral politics. “Without a runoff, Blacks could have run single candidates in races in which there were several white candidates, and, by giving a candidate a plurality of the vote, have some reasonable possibility of winning.”

Elections continued on this way until in 1991, when a federal judge struck down the runoffs rule, saying that it violated the Voting Rights Act. U.S. District Judge Jerome Turner said the city had to adopt a new plan to “eradicate the minority vote dilution.”

Mere months later, Herenton was elected as the city’s first Black mayor—by a hair, with only 142 more votes than his opponent, white incumbent Richard Hackett. The contest was decided in one round, and a runoff very well could have reversed the results, Pohlmann writes.

The racial makeup of Memphis has changed considerably since then; the U.S. census’ 2022 estimates show that 63 percent of the city’s population is Black and 24 percent is white. This has largely eliminated the concern of “minority vote dilution” that the 1991 ruling was intended to address. Still, the no-runoffs rule has remained.

Memphians have devised other informal ways of consolidating the field in intervening years, including holding an unofficial mock election called the Memphis People’s Convention, also known as the People’s Primary. The event was originally put on ahead of the historic 1991 race, and had the effect of galvanizing Black voters around Herenton.

After a long hiatus, the event was brought back in 2019 by the Black Clergy Collective of Memphis as a way to engage and inform voters, give candidates an opportunity to make their case, and signal who the leading candidates might be.

“It’s been important for us not to concentrate on individuals or politicians as much as we concentrate on issues and policies that the majority of the people want to see enacted,” says Fisher of theBlack Clergy Collective.

This year, only six candidates registered for the event, which took place in August, and only two candidates—Young, the president of the downtown commission, and Turner, the former Memphis NAACP president—showed up in person. Young won the mock election, though Fisher stresses that many Memphians remain undecided.

Lexi Carter, chair of the Shelby County Democratic Party, agrees that the People’s Convention this year is less of a political bellwether compared to the first convention in 1991.

“That was effective then, but I think as the years passed the dynamics changed,” Carter told Bolts. She says that people engaged in 1991 “because it was the first time a Black mayor was ever going to be elected. Whereas now, there are African Americans that fill most of the elected positions [in city government.]” The leading candidates in the race this year are all Black and have some attachment to the Democratic party.

The Shelby Democratic Party has largely stayed out of this race, as they have a policy of not endorsing candidates in non-partisan races such as this one, where most candidates are registered Democrats or have Democratic affiliations. “It’s really a very close race and difficult to predict,” says Carter.

As an alternative to the current system, Memphis has tried to adopt ranked choice voting. This voting method, in which voters rank all candidates in order of preference instead of choosing just one, helps ensure that whoever wins has at least some level of support from most voters.

Memphis residents first approved ranked choice with 71 percent of the vote in a 2008 referendum. The city didn’t move to implement it until 2017, though, when Shelby County Elections Administrator Linda Philips announced plans to use it in the 2019 elections. But members of the city council raised concerns about whether voting equipment could handle the change, and Tennessee’s election director Mark Goins halted Philips’ plan, issuing an opinion saying that ranked-choice voting violated state law. The Memphis city council put another referendum on the ballot for 2018, this time asking voters whether they wanted to repeal ranked-choice voting, but that referendum failed when 54 percent of voters rejected repeal.

In 2022, the legislature stepped in to ban ranked-choice voting throughout Tennessee with a law sponsored by Republican state Senator Brian Kelsey, who represents parts of Shelby County. Many Democratic lawmakers who represent portions of Memphis voted against the ban, including Camper, the state Representative who is now running for mayor.

“I voted against the bill because the people of my community were for ranked choice voting. We chose it for ourselves,” Camper told Bolts in an email.

“The legislature likes to lean on and meddle in the affairs of Memphis and Nashville,” she added. “I believe that this is one more way to override the will of Memphis and Shelby County.”

Fisher, who has supported the adoption of ranked-choice voting in Memphis, says he was disappointed to see the option removed.

“I wanna do whatever we can do to ensure that whoever is elected to office, the probability of them representing the will of the majority of the citizens is high and not low,” he told Bolts.

With the path to ranked-choice voting now blocked, one prominent local Democrat is proposing another path to reform: introducing partisan primaries. Jones, the city council president, recently introduced an ordinance that, if passed, would put a popular referendum on the ballot in 2024 to set up a system that would have parties nominating candidates before they face a general election. Mayoral elections in Memphis are currently nonpartisan.

Jones says his ordinance is motivated by the size of the mayoral race, though in a city that is as staunchly blue as Memphis, a one-round Democratic primary could still reproduce some of the current system’s crowding issues. Jones says a partisan primary setting would still help condense the field and encourage candidates to adhere to party values.

He also says it’s less complicated and uncertain than petitioning a court to allow them to bring back runoffs. “Some of the feedback that I’ve received from people has been that there are just way too many people in the race,” said Jones. “So just by doing a partisan basis for selecting the mayor, we avoid having to go to court.”

The Shelby County Democratic Party has endorsed the measure. “We would much prefer to have the opportunity to choose our candidate,” Carter told Bolts. “When we have a nominee in advance, we can really get behind one individual and put all of our resources there, instead of dividing our resources between 16 or 17 people.”

Jones’ proposal has not yet been brought up for discussion by the full city council. It’s not likely to come up until after this election is over.

“It’s a beautiful thing that we have the freedom that anybody who meets the qualifications can get in the race,” said Jones. “I don’t have a problem with that. But when it comes down to making that mayoral decision, let’s make it simple.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.