Michigan Ballot Measure Seeks to Shield State Elections from Trumpian Conspiracies

Proposal 2 would make new strides in expanding ballot access, but the bulk of the measure seeks to defend the state from the shockwaves of the Big Lie.

| October 20, 2022

Michiganders approved a ballot initiative four years ago to expand ballot access. Dubbed “Promote the Vote,” the measure contained reforms that were rapidly spreading around the country, such as automatic and same-day voter registration. It faced little opposition in the run-up to Election Day, and passed handily with 67 percent of the vote.

This November, Michigan residents will decide on another “Promote the Vote” ballot measure, identical in name but introduced under much more hostile circumstances. The constitutional amendment, known as Proposal 2, was crafted in the aftermath of Republican efforts to overturn the 2020 election and the lies that followed about the state’s election systems. Some of its provisions fill in the gaps of the 2018 referendum and further ease voting procedures. But mainly, the initiative is trying to get ahead of the conspiracies—from ballot drop boxes to the funding of local offices—that have taken root in Michigan and surrounding states.

And this time, unlike in 2018, some conservatives are fighting to sink the measure.

“It’s been very frustrating, the general attack on our election process, both ideologically and procedurally,” says Alex Rossman, external affairs director for the Michigan League for Public Policy, an organization that backs Proposal 2.

“There are two facets to the current proposal,” he explained. “One is that proactive piece in continuing to open up voting and make it easier for everyone. But unfortunately there is a defensive piece too.”

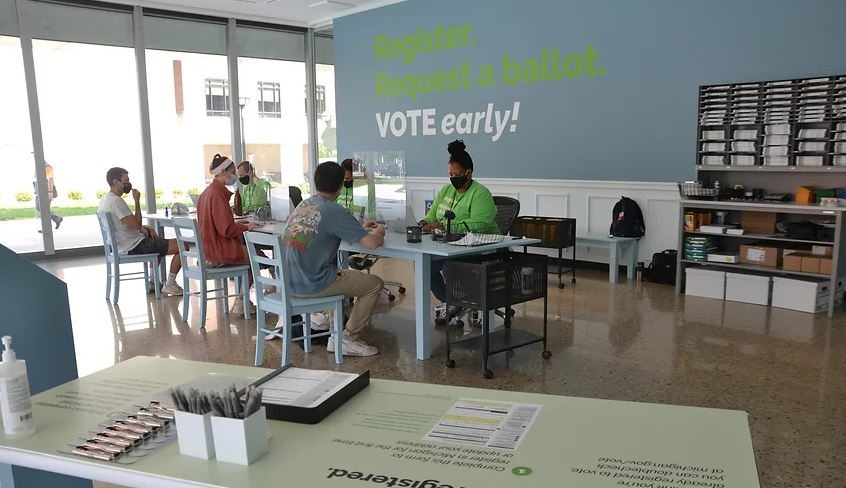

Of the nine key sections in Proposal 2, some would make new strides in expanding access. Most significantly, it would establish nine days of early in-person voting in the state. Right now, Michiganders who want to vote in-person before Election Day can do so in their local clerk’s offices with an absentee ballot, instead of having broader access to polling stations and voting machines. The measure would also supply state-funded postage to vote by mail, and create new mandates for townships to set up ballot drop boxes.

“It’s the role of our government to make sure people have the ability to vote and aren’t bogged down by constructed barriers,” says Branden Snyder, co-executive director of the group Detroit Action, another member of the coalition that backs the measure.

But much of Proposal 2 is driven by a separate goal: to protect Michigan’s election systems from the shockwaves of the Big Lie. The measure contains provisions to protect the process of certifying results to lower the chances that an election is overturned, and to narrow who can audit election results to prevent an Arizona-style spectacle.

Election deniers may gain more power in Michigan this fall as candidates aligned with former President Donald Trump are also running for secretary of state and attorney general. For proponents of Proposal 2, these circumstances make it urgent to strengthen the protections embedded in the state constitution.

Widespread conspiracies about voter fraud surrounding the 2020 election set off a pattern of right-wing attacks on voting access in Michigan that manifested in the legislature and in election-governing bodies practically from the moment votes were tallied on election day.

The afternoon after the election, poll challengers stormed a large polling place in Detroit during the last election in an attempt to halt the vote count. The scene became so rowdy that some had to be escorted away by police. Over the following weeks, the board of canvassers in Detroit’s Wayne County, a Democratic stronghold, nearly failed to certify election results after the two Republican members initially voted not to certify based on imbalances in the poll books, without pointing to evidence of fraud. The board eventually certified the results, but only after hours of uncertainty that riveted the nation.

Even after Joe Biden was declared the winner, Trump continued to falsely allege widespread fraud in Detroit, which led groups loyal to the former president to file a petition for a “forensic audit” of the results in 2021. The petition provided for the audit to be funded privately, with sources remaining anonymous. The independent audit has not happened, but an official audit conducted by the state found no evidence of significant fraud.

Proposal 2 is meant to forestall such scenarios in the future and strengthen the hands of those who would fight back.

One provision would specify that, when they fulfill their role of certifying election results, county and state boards of canvassers are allowed to consider nothing but “the official records of votes cast” and aggregating them. This is their ““ministerial, clerical, nondiscretionary,” the text says.

Election law experts consulted by Bolts said Michigan law already disallows canvassers from doing more, for instance by purporting to conduct their own investigations. But they were mixed on whether adding language in the state constitution about this would make a difference.

Leah Litman, a professor of law at the University of Michigan, told Bolts in September that some Republican canvassers still went rogue in the past and that they may try to bend the law again But John Douglas, a University of Kentucky professor specialized in election law, believes the addition may still be meaningful. “It’s not harmful to lay it out so it’s abundantly clear,” he said.

“I think that makes it even clearer to the canvassers that they can’t choose not to certify,” he added. “It gives them much less wiggle room to try to justify their actions.”

Proposal 2 would also establish that only election officials such as the secretary of state can conduct post-election audits, not private groups. And it would require that all audit funding be publicly disclosed. These reforms would remove the possibility of any “forensic audit” funded of the sort that Trump supporters tried to push for in 2021.

The constitutional amendment would also address some of the voter restrictions championed by Republican lawmakers since 2020. State senators last year introduced a sweeping package of 39 bills that targeted aspects of the 2020 election that became conservative flashpoints.

Some of the bills targeted ballot drop boxes, which have become a heated target of fraud conspiracies in Michigan and elsewhere (they are no longer even available in Wisconsin) despite widespread evidence that they are safe. Another swath targeted the availability of absentee voting; it prohibited local clerks from providing prepaid postage on absentee ballots and from mailing absentee ballot applications to voters who did not request one.

Absentee voting was authorized without an excuse in Michigan by the 2018 constitutional amendment, and implemented in a major election for the first time in 2020.

“Part of the challenge in Michigan is that the 2020 election was when those 2018 reforms took hold,” Rossman said. “So they were unfortunately made into a scapegoat by some individuals questioning the election outcome.”

Michigan Republicans also tried to pass a bill that would have barred local governments from accepting outside donations to help fund elections systems. The bill came out of the right-wing backlash that greeted the 2020 grants made by a national foundation that distributed money donated by Facebook founder Mark Zuckeberg and Priscilla Chan to local offices nationwide, to help them prepare and run elections during a pandemic; close to 500 cities and townships obtained those grants in Michigan alone.

Since 2020, other states have passed such legislation since 2020, including new limitations on mail-in voting and bans on local governments accepting donations. But these bills had no chance of becoming law this past session given Democratic Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s veto power. (Whitmer is up for re-election this fall.) Secure MI Vote, a committee that is backed by a GOP-aligned dark-money group and that has also received donations from the Michigan Republican Party, championed a ballot measure that would have put many of these measures to voters directly, circumventing the governor. But the organization did not gather enough signatures by the filing deadline and their initiative won’t appear on the November ballot.

Instead, voting rights proponents managed to qualify Proposal 2, which aims to put language into the state constitution that would close the door to many of these restrictions.

Proposal 2 would require municipalities to have at least one drop box for every 15,000 voters; the provision also requires that they be accessible 24 hours a day in the 40 days before election day, up to 8pm on election day.

Proposal 2 would also allow local governments to accept outside grants as long as all donations are disclosed, a response to the controversy around the 2020 grants. And it would further ease the availability of mail-in voting: It would require state funding for postage for absentee ballot applications and ballots and also allowing voters to opt-in to a list to receive absentee ballots in all future elections.

Snyder says organizers wanted to create more opportunities for people to vote who may not otherwise. “If I have a disability, if I’m a person who needs more time to review, being able to vote at home, being able to vote absentee, allows more participation,” he said. “We see that as a practical solution to the apathy that people have towards elections.”

But Sharon Dolente, a senior advisor to the Promote the Vote coalition, told Bolts that she has noticed “a lot more opposition this time than there was in 2018. I do think the reason why we saw this is that [voting] has become a more political issue.”

For one, Republicans almost knocked Proposal 2 off the ballot. In August, the Republican members of the state Board of Canvassers overrode the recommendation of state staffers, in a dress rehearsal of GOP efforts to skew election outcomes, and they voted to disqualify Proposal 2 on the basis of the petitions’ typography; they did the same for another amendment that protects abortion rights. The Michigan State Supreme Court intervened in a pair of 5-2 decisions.

Since then, critics like Secure MI Vote have pivoted to campaigning against Proposal 2. With social media posts, yard signs, and mail flyers, the group has made the case that Promote the Vote would compromise election security. Part of their argument is that mail-in voting is unsafe. They also contend that the measure has lax voter ID laws: Proposal 2 includes a provision allowing voters to prove their identity with either a photo ID or signed affidavit. In actuality, this only continues the status quo: State law already allows a sworn affidavit as an acceptable form of voter ID.

At least one text messaging campaign, reported by Bridge Michigan, falsely claimed that Proposal 2 would give people incarcerated in state prisons the right to vote. Michigan law currently prohibits this, and the proposal includes no language to the contrary. Bridge Michigan tied the text messages to a newly-formed political committee run by a conservative operative.

Despite this, Proposal 2 seems likely to pass. A September poll conducted by the Glengariff Group for a local news outlet showed that 70 percent of likely voters supported the measure; the poll also found that Republican-leaning respondents backed it as well.

Snyder finds that when he talks to voters—especially Black voters—about the initiatives contained in Proposal 2, and the opposition it is trying to overcome, people are incredulous that lawmakers would clamp down on their voting rights in the name of rooting out fraud—especially given the activities of the past two years.

“You’ve got people that are angry, saying, ‘You’re trying to say that we’re cheating?’” Snyder said. “You get people that are fired up, saying, ‘you’re not gonna steal my vote.’”