Minnesota’s Voting Rights Act Preserves This Key Protection A Federal Court Has Erased

Minnesota ensured that voters and private groups can sue over VRA violations, restoring a longstanding right that federal judges had gutted last fall.

| September 4, 2024

Conservative judges on the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals last fall dealt a near-fatal blow to the Voting Rights Act, the landmark federal law, in the seven states the circuit covers. Breaking precedent, the court ruled that advocacy organizations and private citizens can no longer file lawsuits alleging violations of the VRA. Instead, only the U.S. Department of Justice can do so.

The ruling is certain to deter voting rights litigation within the Eighth Circuit, and advocates worry that the U.S. Supreme Court could take the rule nationwide. Since the 1980s, outside organizations have pursued the vast majority of VRA cases since the DOJ doesn’t have the resources, and in many cases the political will, to pursue many lawsuits on its own.

But lawmakers in Minnesota looked for a remedy this year, and Minnesota has now become the first state within the Eighth Circuit to enshrine a private right of action into state law. Governor Tim Walz in May signed the Minnesota Voting Rights Act, which spells out protections for voters and allows private citizens and outside organizations to bring lawsuits in state courts.

For David McKinney, an attorney at the ACLU of Minnesota who supported the law, the reform “honors a tradition and sets a value under Minnesota law that individuals, when their rights are violated, they’re the ones that are best positioned to assert it.”

“They are the folks who, under the theory of their case, can’t vote, right? They’ve been unlawfully discriminated against, and so they’re in the best position to assert their rights,” McKinney continued.

The Minnesota Voting Rights Act was adopted as part of a package that contains other voter protections, like an end to prison gerrymandering. Voting rights advocates told Bolts that the Eighth Circuit’s ruling supercharged their push, and ensured that enshrining a private right of action would be part of the bill. Several other states have passed similar laws in recent years to shield voters from voting rights’ federal erosion.

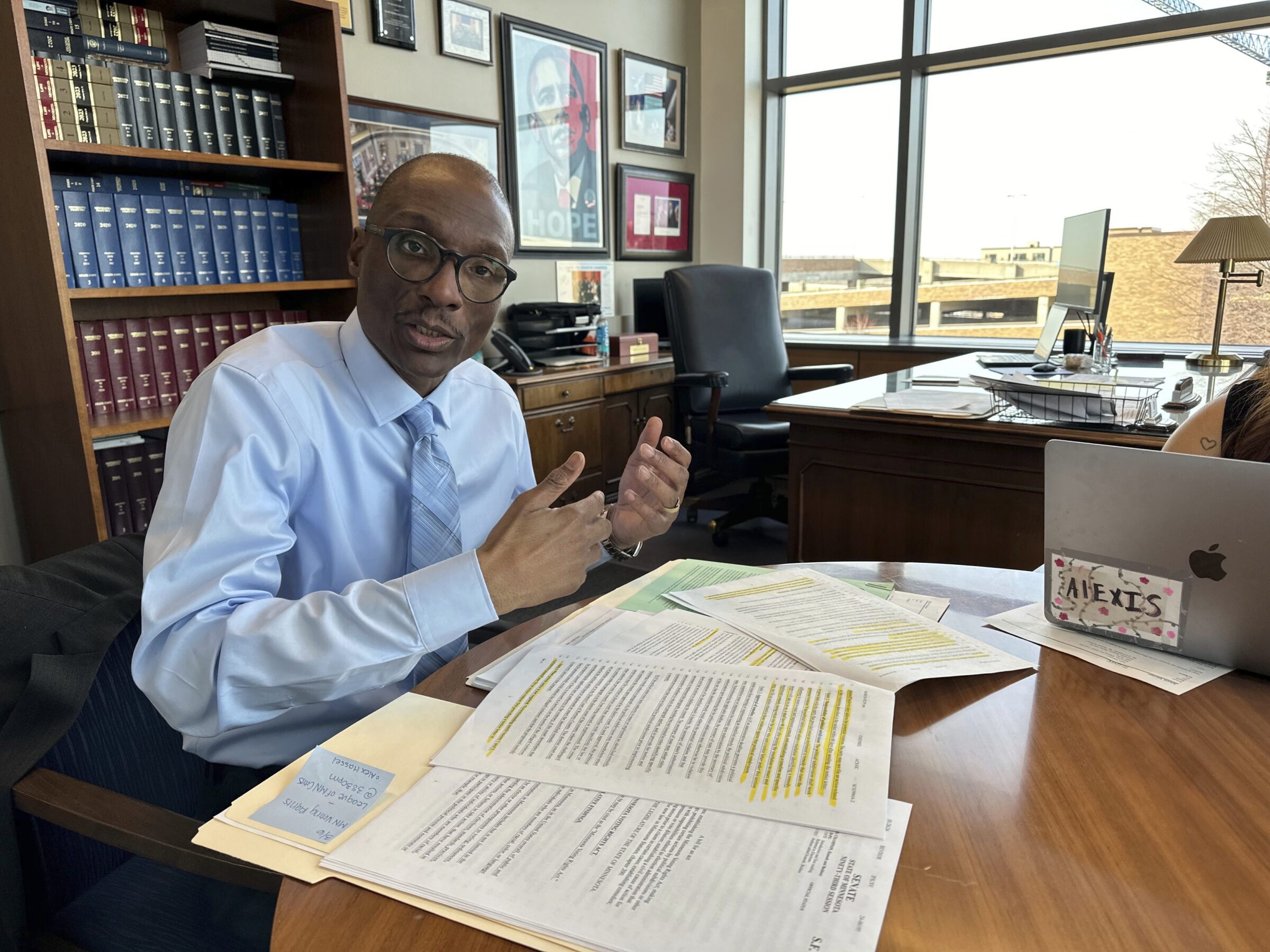

“It was the Eighth Circuit decision that added the urgency by taking away the ability of Minnesotans who have been discriminated against to go to court and enforce their rights under federal law,” explains Emma Greenman, a state Representative who co-authored the bill, along with Minnesota Senate President Bobby Joe Champion. Greenman pointed to the fact that two thirds of Voting Rights Act cases are brought by private plaintiffs or organizations. “The U.S. Attorney General is a piece, but not a big piece, of the way that the federal rights are enforced.”

Often, individuals or groups that are being discriminated against are represented in court by organizations such as chapters of the ACLU or NAACP. “Litigation is expensive, and so you do require a fair amount of resources to successfully bring a case. And I think a lot of these organizations do have resources that individual citizens might not have,” said Justin Erickson, general counsel in the Minnesota secretary of state’s office. “A lot of these organizations are doing this work throughout the country, so they have a really good grasp of the trends that are out there, the different work that’s being done, the best practices that different agencies have undertaken in order to protect voting rights.”

The Eighth Circuit, in a ruling authored by Judge David Stras, a former Minnesota justice who was nominated to the federal bench by President Donald Trump in 2017, has threatened to halt a lot of that work.

Before the decision came down, the Minnesota bill’s crafters had been weighing whether to include language codifying a private right of action. While the federal VRA doesn’t include a provision saying explicitly that private citizens can sue for violating the law, Americans have for decades sued under Section 2 of the VRA; in 1996, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed this right for private individuals and organizations alike. Greenman says there are also many aspects of federal voting rights law that aren’t explicitly mentioned in the VRA but have been affirmed by courts, which can make legal proceedings complicated.

But given the current conservative majority on the U.S. Supreme Court, Greenman and her allies wanted to be more proactive in protecting rights. “What was a simple and very eloquent bill has been made more and more complicated, especially since we’ve had a Supreme Court that has really been hostile to its protections,” said Greenman.

They looked to these federal court precedents, as well as to VRAs that were popping up in other states, championed by well-known national organizations like the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, the Campaign Legal Center, and the Brennan Center for Justice. Greenman described the thought process as, “How do we provide strong protections in light of what’s happening to the federal Voting Rights Act?”

Lilly Sasse worked on Greenman’s state House campaign, and now works for We Choose Us, a coalition of groups that support stronger voting rights protections in Minnesota. Sasse said that the coalition began in 2021, but the campaign became much stronger after the Eighth Circuit decision. “In order for people to have those protections from voter suppression, vote dilution, their day in court, we needed to have something in Minnesota that explicitly stated that.”

Eight other states have adopted their own Voting Rights Acts—California, Connecticut, Illinois, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Virginia, and Washington. Greenman said she and her colleagues looked to these existing laws and to other states still considering their own state-level VRAs, including Michigan and Maryland, as they drafted their own bill. “It’s always impossible to use a specific model, because all states are so different,” she said.

In part, these laws are a way for a state to go beyond the floor of federal voting protections, and enshrine more specific rights relevant to its particular communities. New York’s VRA, for example, guarantees ballot access in languages other than English.

But they’re also a reaction to worries that courts could further erode federal voter protections. “In recent years, federal courts have been spending some time stripping the VRA of critical components and creating a body of case law that can make it extremely difficult for plaintiffs to win their cases,” said Lata Nott, of the Campaign Legal Center.

Last year’s Eighth Circuit decision came out of a dispute over a redistricting plan in Arkansas. Liberal groups in that state, including local branches of the ACLU and NAACP, announced in July that they won’t appeal the circuit court’s ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court, and will instead seek redress under other laws, even though they believe it was wrongly decided. An adverse ruling by the Supreme Court could end a private right of action nationwide. But in the meantime, the right to sue in federal courts has virtually ended across the Eighth Circuit, which besides Minnesota covers Arkansas, Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska, and the Dakotas.

“With the Eighth Circuit now having significantly curtailed private causes of action under the Voting Rights Act, and who knows what the Supreme Court’s gonna do on this one, what at least happens in Minnesota now is that voting rights are protected under state law, and individuals now have this ability to enforce their own voting rights,” said David Schultz, a professor of political science and law at Hamline University in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Another key protection of the federal VRA gutted by federal courts is Section 5, known as the preclearance requirement. Under it, jurisdictions with a history of racial discrimination had to get federal approval before making changes to voting rules. But the U.S. Supreme Court’s Shelby County v. Holder ruling struck down Section 5 in 2013, giving the issue greater significance at the state level.

New York and Connecticut have both added preclearance provisions into their state VRAs, requiring that jurisdictions with a history of discrimination get approval, either from state officials or courts, for proposed voting changes before they can be implemented. Nott said her organization has pushed for preclearance requirements in state VRAs, but this didn’t make it into the Minnesota law.

“We’re hoping, actually, that next session, that’s something that we can try to push forward,” she said. “With the Eighth Circuit decision, there was some emphasis on being able to pass a bill that could protect the rights of Minnesotans to assert their own rights in court.”

Experts also point to Minnesota’s particular racial disparities in voter turnout as a reason why the state law is necessary. Today, slightly more than a fifth of Minnesotans are people of color, roughly double the population of 30 years ago, according to Schultz. “Minnesota remains a state with enormous racial disparities in criminal justice, education housing, et cetera, but one of the other major racial disparities in the state of Minnesota,” Schultz said, “is voter registration and turnout.”

“A lot of people say the state of Minnesota is usually the north star when it comes to voter turnout. But I also think that we need to stop and ask, for who? For who is the state of Minnesota the number one in voter turnout?” said Annastacia Belladonna-Carrera, executive director of the Minnesota chapter of Common Cause. Belladonna-Carrera and her organization helped campaign for the Minnesota VRA. “Most of the categories where the state of Minnesota does outshine the rest is in the disparities,” said Belladonna-Carrera.

In part because of how recently the law was enacted, no lawsuits have yet been filed under the Minnesota Voting Rights Act. Belladonna-Carrera said that Common Cause Minnesota is “entertaining a couple of potential cases” but nothing is definite yet. Nott, of the Campaign Legal Center, said that even in the other states with their own VRAs, there’s “not a huge number” of cases yet. “People fear that passing one of these will lead to a torrent of litigation. That’s not the case,” she said.

“These cases are not easy,” acknowledges Greenman. “They have a very high burden of what you have to prove.” But that’s why she believes it’s important for voters to know it’s a right they may exercise.

“Without a private right of action,” she continued, “what it would mean is you would have to wait for the discretion of a government official to decide whether to bring that case or not, and it would just depend on the resources that the attorney general had.”

Correction: This article has been updated to include a mention of New Mexico’s Voting Rights Act.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom: We rely on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.