New Mexico Officials Block a Pathway to Freedom for Juvenile Lifers Despite Reforms

State lawmakers banned life without parole for juveniles. But an opinion by the attorney general and parole board decisions could keep some from getting a second chance.

| December 22, 2025

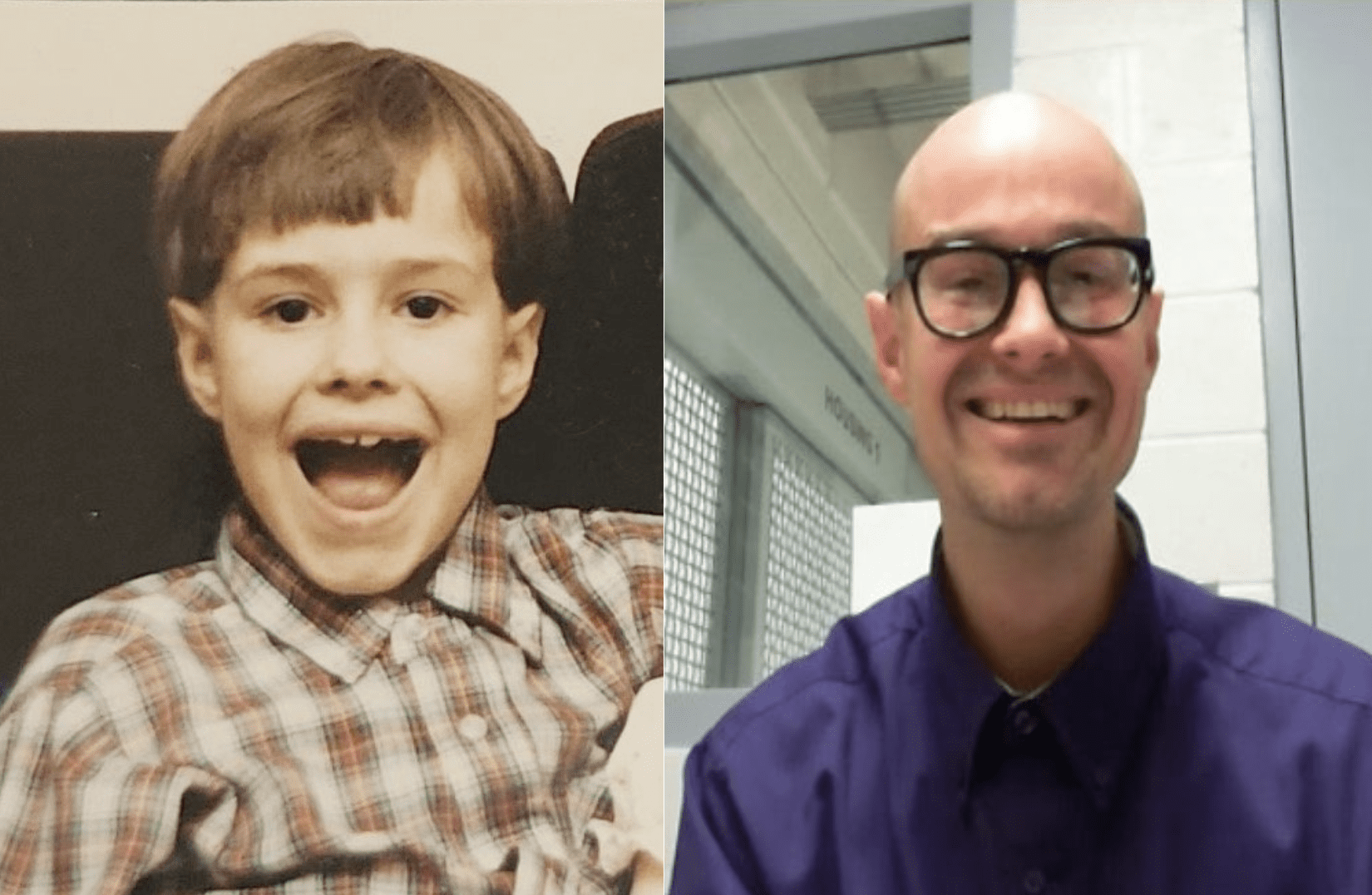

Sarah Htoutou has always been close with her brother, Jesse Tooker. As children, she remembers him comforting her whenever she had bad dreams, or inviting her to tag along to hang out with his friends even though she felt like “the annoying little sister.”

The siblings remained close even after Tooker was sent away to prison for the rest of his life at the age of 17. Then two years ago, after New Mexico lawmakers abolished life without parole for juveniles, creating a pathway for Tooker’s release, Htoutou began planning for her brother to come home after nearly three decades in prison. She made arrangements to purchase a townhouse for him down the street from her and found him a full-time job at a meat packing plant. She talked with a local pastor who agreed to regularly meet with and counsel her brother. She was looking forward to helping him get a driver’s license and bank account.

“We set it up so that he could be the most successful that he could be. It was so exciting to help him build this life and to have our family back together,” Htoutou told Bolts.

At Tooker’s parole hearing this past August, his legal team presented evidence that he had changed behind bars. They pointed to the 35 programs he completed in prison, including welding, a course on brain health, and getting his high school diploma. They also stressed that he has gone to therapy twice a week and has worked as a peer educator and ministry mentor to other prisoners helping them learn skills while keeping a clean disciplinary record. His application included letters of support from prison staff and family members.

The parole board granted Tooker parole on the life sentence he received for murder.

And yet the parole board wouldn’t agree to release him. After the board paroled Tooker for the life sentence he received as a juvenile, New Mexico’s Democratic Attorney General, Raúl Torrez, released an opinion that effectively advocated for keeping him behind bars. According to Torrez, who represents the parole board in his role as AG, people granted parole under the state’s Second Chance Act are still bound by any other consecutive sentences that were tied to the underlying case that resulted in their life sentence. In Tooker’s case, that means the state now expects him to serve out a 22-year sentence for a burglary conviction that was stacked on top of his life sentence for murder in the same case.

Under Torrez’s interpretation of New Mexico’s Second Chance Act, which Tooker’s lawyers say conflicts with the plain language of the reform law passed in 2023, Tooker and others with consecutive sentences could remain in prison even longer. His opinion also threatens to send back some people who have already been released under the law.

“It was just devastating,” said Htoutou of learning of the decision. She backed out of the deal for the townhouse and scaled down Thanksgiving this year. It was the smallest one she’d ever had.

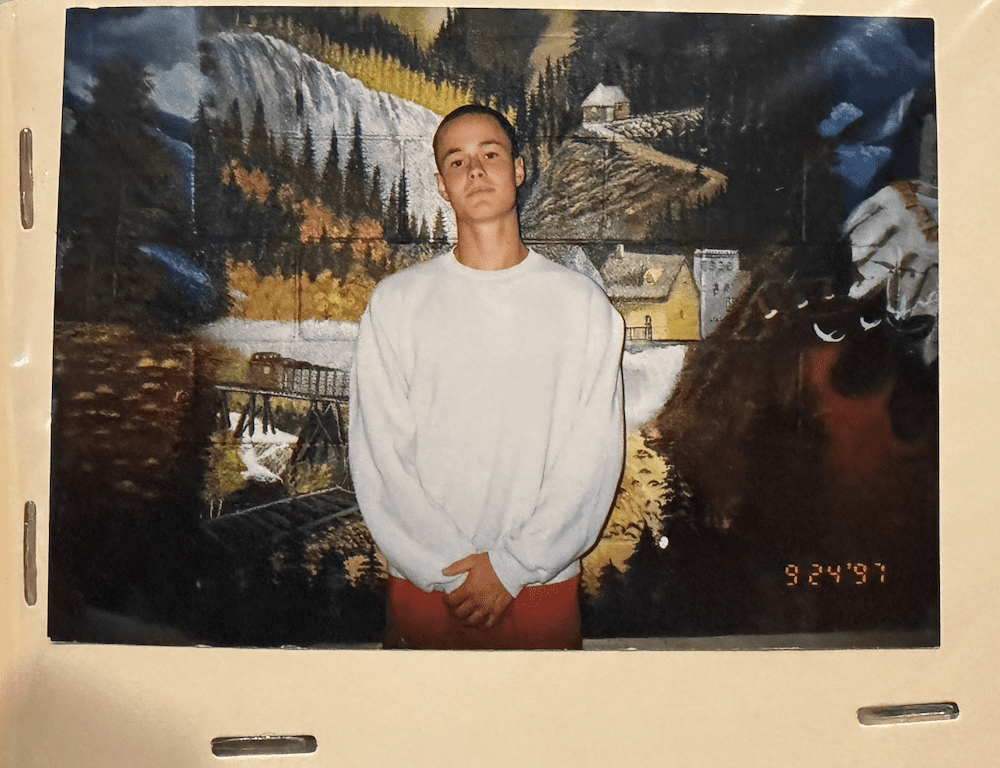

In 1995, Tooker ran away from home in South Dakota and was stranded in New Mexico with five other teenagers and a 20-year old man without any money. He’d gone days without food or sleep and was surviving on meth, alcohol, and cigarettes. Tooker and his friends broke into 63-year-old Martha Murphy’s Farmington home, in the northern part of the state, ransacked it, and stabbed her to death. They stole her pickup truck and drove to Kansas, where police arrested the crew. Tooker pleaded guilty to Murphy’s murder and received a life sentence with an additional 22 years for burglary.

“When he went away, I was in disbelief and angry and upset,” said Htoutou. “The work he’s done since then has been absolutely amazing.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

See more of our reporting on juvenile life sentences

Then in the spring of 2023, lawmakers passed The Second Chance Act abolishing life without parole for juveniles, making New Mexico one of 28 states to ban that sentence for children. The law fell in line with decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court that determined children in the criminal legal system should be treated differently because their brains are not fully developed and therefore more vulnerable to poor decision making.

The law created an opportunity for prisoners convicted of a crime they committed while under the age of 18 to have a chance at freedom via parole after either 15 to 25 years behind bars.

Advocates estimated that around 85 people became eligible for resentencing.

Tooker was denied the first time he appeared before the parole board that November. The board wrote in a letter that his “case was a very difficult decision for [us] that involved a great deal of thoughtful debate.” It recommended that Tooker continue to engage in education and self-reflection, and explore additional therapies and mental health counseling.

At issue in Tooker’s case is the 22 years he was sentenced to consecutively for burglary along with his life sentence. According to the Second Chance Act, “Parole eligibility and a parole hearing shall occur whether the offender is serving concurrent or consecutive sentences for multiple convictions arising from the same case.” People who have multiple convictions for unrelated offenses, however, still have to serve their next sentence after they are paroled.

Yet Torrez’s opinion, issued in October, made no such distinction between stacked sentences for the same underlying offense versus multiple sentences for separate and unrelated cases, stating, “Even if a serious youthful offender is granted parole under [The Second Chance Act] that offender is not thereafter released from serving a consecutive sentence or sentences to which they may also be bound by court order.” Tooker’s lawyers argue that the attorney general misinterpreted the law, which they say was constructed specifically to allow for people like Tooker to be released.

They’ve also filed a separate request to bar the parole board and New Mexico Department of Corrections from sending back at least one woman and an unknown number of others to prison because of Torrez’s interpretation.

In a legal filing on behalf of people already paroled, lawyers argue that the legislative history of the Second Chance Act shows that lawmakers deliberately amended the law’s language to differentiate between people serving time for one case versus multiple cases, and that Torrez’s interpretation of the law is erroneous.

Lawmakers in early November held an emergency hearing to discuss the attorney general’s opinion. State Senator Antoinette Sedillo-Lopez, a sponsor of the 2023 law, said that she and her fellow politicians had already worked to clarify how prisoners like Tooker should be treated under the Second Chance Act.

“It is as clear as we could possibly make it,” she said during the hearing. “I don’t know how we could make it more clear.”

Legislators said during the hearing that they would await the decision from the lawsuits before making a decision on whether to pass a new law to change the language of their 2023 act.

As the courts decide, people already released under the Second Chance Act have said they feel like they’re living under threat of being sent back to prison because of the AG’s opinion. “It doesn’t matter if we change for the better,” one person on parole told The Santa Fe New Mexican in November. “I’ve spent the last two years overcoming the trauma from the institutionalization of doing that much time, and then the thought of going back and being in the middle of it again—it’s frightening, it’s terrifying.”

A spokesperson for the Department of Corrections has said that the agency would not seek to reincarcerate anyone unless ordered by the parole board and that no one has been sent back to prison.

The legal battle over the interpretation of New Mexico’s Second Chance Act could drag on for years. After the Massachusetts supreme court in 2013 banned sentences of life without the possibility of parole against minors, the state continued to hold people with life sentences to serve a consecutive sentence for the same underlying offense—a conflict that the state’s courts didn’t resolve until 2021, after people who’d been kept in prison sued and won.

And after Rhode Island passed its own second chance legislation in 2021, Attorney General Peter Neronha, also a Democrat, fought to keep a man who was sentenced to life when he was 17 incarcerated because he had a consecutive sentence, despite him meeting the criteria under the state’s new reform law. The courts decided in the man’s favor last year.

Julie Casimiro, a Rhode Island representative who sponsored that legislation, wrote a letter to New Mexico lawmakers in November warning of the consequences of the attorney general’s misinterpretation. “Becuase of this interpretive dispute, Rhode Island endured protracted and costly ligation,” wrote Casimiro.

Lynette Labinger, an attorney who represented prisoners in the Rhode Island litigation, told Bolts that she was disappointed that Neronha, who promised to support criminal justice reforms shortly after becoming Rhode Island AG, made it more difficult for prisoners to win their freedom under the reform law.

“One of the few things that people have when they’re behind bars is hope, and everything that crushes it is a heartbreak. So we’re very glad to have resolved that, taken that interpretation off the table,” she said.

Torrez, the New Mexico attorney general, had previously advocated for children in the criminal legal system, signing onto a 2022 letter advocating for federal reforms for prisoners sentenced as juveniles. But some Democrats have turned toward more punitive policies in recent years, and his opinion this year coincides with an increased focus on juvenile crime in the state, with Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham earlier this year criticizing lawmakers for not addressing the issue following a mass shooting at a park in Las Cruces that left three people dead and 15 people injured. Three of the four charged with the shooting are teenagers.

Republican lawmakers this month convened as part of a public safety task force to discuss juvenile crime and tougher laws they say will hold kids accountable.

But the fate of Torrez’s opinion is now in the hands of judges rather than Lujan Grisham. Stephen Taylor, executive director of legal advocacy organization, De-Serving Life, is representing parolees, including Tooker, in a lawsuit against Torrez. He told Bolts of Tooker, “He’s confident we’re going to win, you know, and that the law will become clear for other people to be able to go home, too.”

On Wednesday, a Santa Fe district judge held a hearing on Tooker’s request to reverse the parole board’s decision to keep him incarcerated. The judge ruled against releasing Tooker because of procedural reasons, but Htoutou, who attended her brother’s hearing, said she felt encouraged by the judge’s willingness to hear his case. “For the first time since August it seems I might get my brother back after all.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.