New Mexico Is Making It Easier to Vote

The state adopts a bill to restore voting rights to thousands on probation and parole. It will also strengthen ballot access for Native voters and further automate voter registration.

| March 13, 2023

Editor’s note (March 30): The governor signed House Bill 4 into law on March 30.

Adam Griego, who has battled trauma and addiction for most of his life, felt he was treated as subhuman when he was in prison. Over three months in solitary confinement, he recalls, he was forced to drink water out of his hands because he wasn’t given a cup. He labored eight-hour days in a recycling yard, rifling through trash, for $10 a week. When he was released in 2020, he had only $125 to his name and couldn’t find a job despite 20 years of experience as a car technician.

“Once you commit a crime and you’re convicted, you sort of are defined by your choices and the fact that you’ve been convicted,” he told Bolts. “It makes your return back into society extremely difficult.”

To this day, Griego is not allowed to vote. He resides in New Mexico, a state that withholds voting rights from people while they are in prison, on probation, and on parole over a felony conviction, and Griego isn’t set to finish probation until the fall. Now sober, on staff at a Subaru dealership, and an adjunct professor at a technical college, he’s proud of what he has accomplished.

“So for any politician to look at me then and say I haven’t completed my sentence, I don’t deserve the right to vote, is absurd,” Griego said. “Some people want to keep the formerly incarcerated population exactly where they’re at. That’s why the voting rights issue isn’t a political one; it’s more of a human rights issue.”

Griego now volunteers with OLÉ, a civil rights group in New Mexico that for years has called on the state to expand voting rights, alongside other local organizations. Lawmakers answered their call this week.

The state legislature on Monday adopted House Bill 4, an omnibus voting rights bill known as the New Mexico Voting Rights Act, sending it to the governor’s desk. Among many provisions, HB 4 enables people to vote while on probation and parole. This would immediately restore the voting rights of roughly 11,000 New Mexicans like Griego; and going forward, many others would regain the franchise upon release, though the bill would not help people while they are incarcerated.

“I can’t stop crying,” Griego texted after the state Senate passed the bill last week. The House first passed the measure in February and it concurred with the Senate amendments on Monday.

HB 4 now heads to Democratic Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham, who supports it and is expected to sign it.

When she does, New Mexico will become the 26th state, plus D.C., where at least anyone who is not in prison can vote. Minnesota took this same step earlier this month.

Proponents of the move made the case that it will give people more of a stake in the places they live. “When people have a sense of belonging in the community, they’re less likely to inflict harm on themselves and others,” Justin Allen, a New Mexico advocate who is himself formerly incarcerated, told Bolts. “This legislation is about welcoming people back and allowing them to participate in a functioning society.”

HB 4 was championed by Democratic lawmakers, and every voting Republican lawmaker in both chambers opposed it. All but two Democrats who took part in the vote supported the bill (House Democrats Ambrose Castellano and Joseph Sanchez opposed its initial passage, though they each supported it when it returned to the chamber on Monday).

It contains a flurry of other measures that are meant to strengthen voting rights in the state, including the establishment of Election Day as a state holiday and the expansion of ballot access on Native land. Native people living on reservations in New Mexico did not gain the right to vote until 1948, and HB 4 addresses continued hurdles by requiring language translation at the polls, reducing the distance people on reservations must travel to cast a ballot, and allowing input from tribes on where voting precinct boundaries are set.

“This is a huge step in the right direction,” said Ahtza Chavez, executive director of NM Native Vote, an organization that advocates for the rights of Native people. “Tribes, Pueblos, and Nation will now have a Native American Voting Rights Act section in the [New Mexico] election code to build upon.”

The bill would also further automate the state’s registration system. Under the new program, the state would automatically register eligible New Mexicans when they interact with the Motor Vehicle Division, for instance while renewing a license; these new voters would later receive a mailer at home enabling them to opt out if they choose. Currently, people are asked to decide immediately, while they are still at the MVD.

Colorado made this same switch in 2019—delaying the stage at which people are asked if they want to opt out—and that resulted in a dramatic jump in the number of registrations.

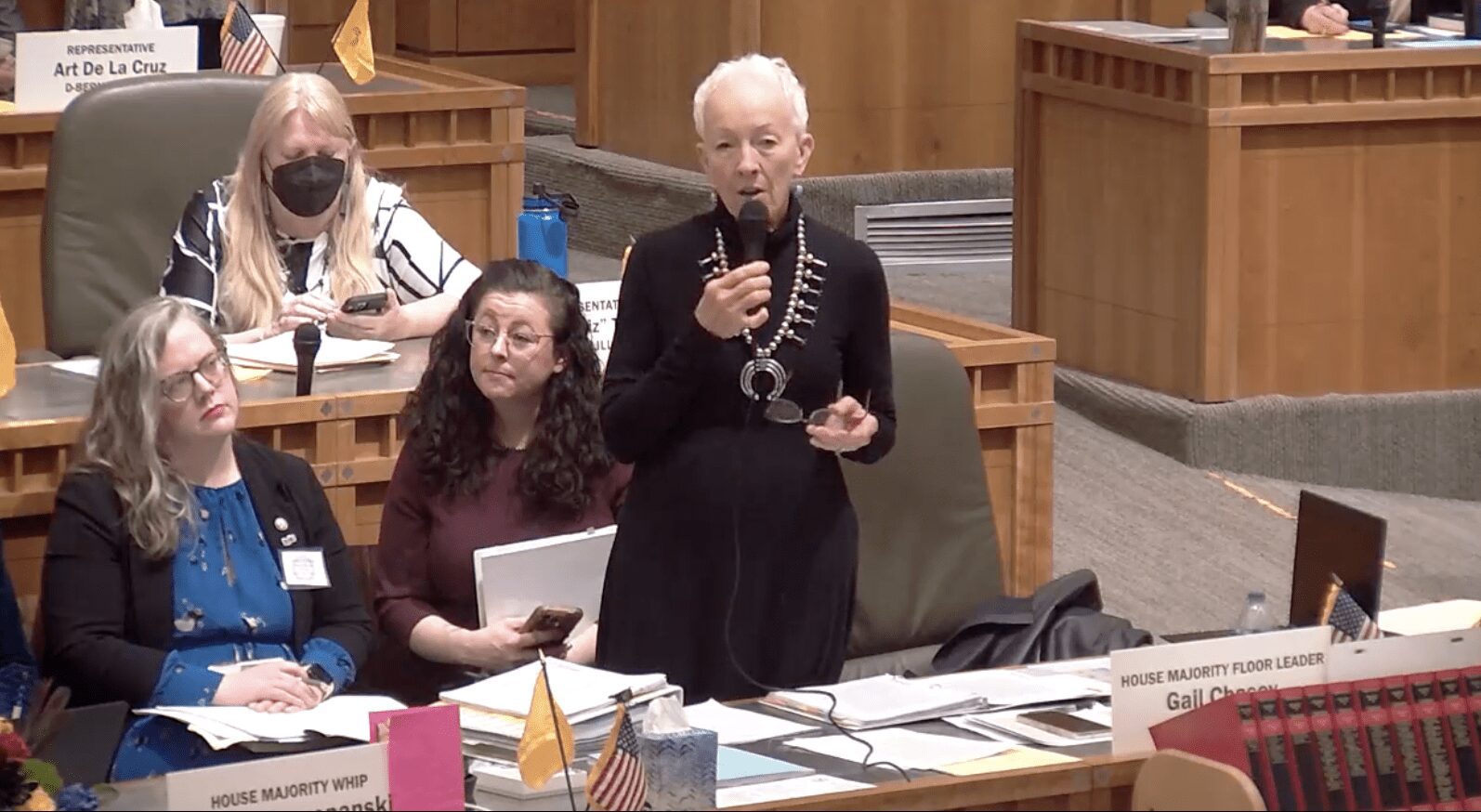

The lawmakers who have championed HB 4 are eager to emulate Colorado and other places that adopted this system, known as “back-end” automatic voter registration. “If other states’ experiences are instructive,” said Democratic state Representative Gail Chasey, one of the bill’s chief sponsors, “we’ll have only five percent [of new registrants] who choose not to stay engaged.”

State Democrats had pushed similar voting reforms for years but repeatedly hit a wall. Last year, another package containing many of the same provisions derailed at the finish line because it was filibustered into oblivion by Republicans, though voting rights advocates also told Bolts that they blamed the intransigence of a Democratic senator who slowed down the bill and opposed automatic voter registration.

But Democratic lawmakers shed some of their farthest-reaching proposals along the way. Last year’s iteration would have lowered the voting age to 16 in local elections, a step that HB 4 does not take.

HB 4 will also continue disenfranchising the roughly 5,000 New Mexicans who are imprisoned over a felony conviction. When Chasey first introduced a bill targeting felony disenfranchisement in 2019, she went for a bolder reform: abolishing it altogether.

Her proposal, filed shortly after Democrats won full control of the state government, would have let every citizen vote, including while they are incarcerated. At the time, only Maine and Vermont allowed people with felony convictions to vote from prison (Washington, D.C., joined them in 2020), and those two states are largely white. In New Mexico, communities of color are consistently criminalized at elevated rates and thus are disproportionately deprived of the right to vote.

During the state’s most recent elections, according to the Sentencing Project, Latinx people in New Mexico were nearly twice as likely to be barred from voting as white people. For Black New Mexicans, the rate was four times higher.

Chasey quickly found many of her fellow lawmakers weren’t on board with enabling all citizens to vote. “They were like, ‘You mean you’re going to let them vote, too?’” she recalls them saying. “As if it’s a privilege, which it’s not. It’s a civil right.”

Allen, who supports expanding the ballot further to include incarcerated people, says he expects that HB 4 will move the conversation forward. “It’s a big step towards universal suffrage,” he said. “These things take time.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Our weekly newsletter on the local politics of criminal justice and voting rights