In New Orleans, a Police Veteran Will Take the Helm of a Jail Marred by Abuses

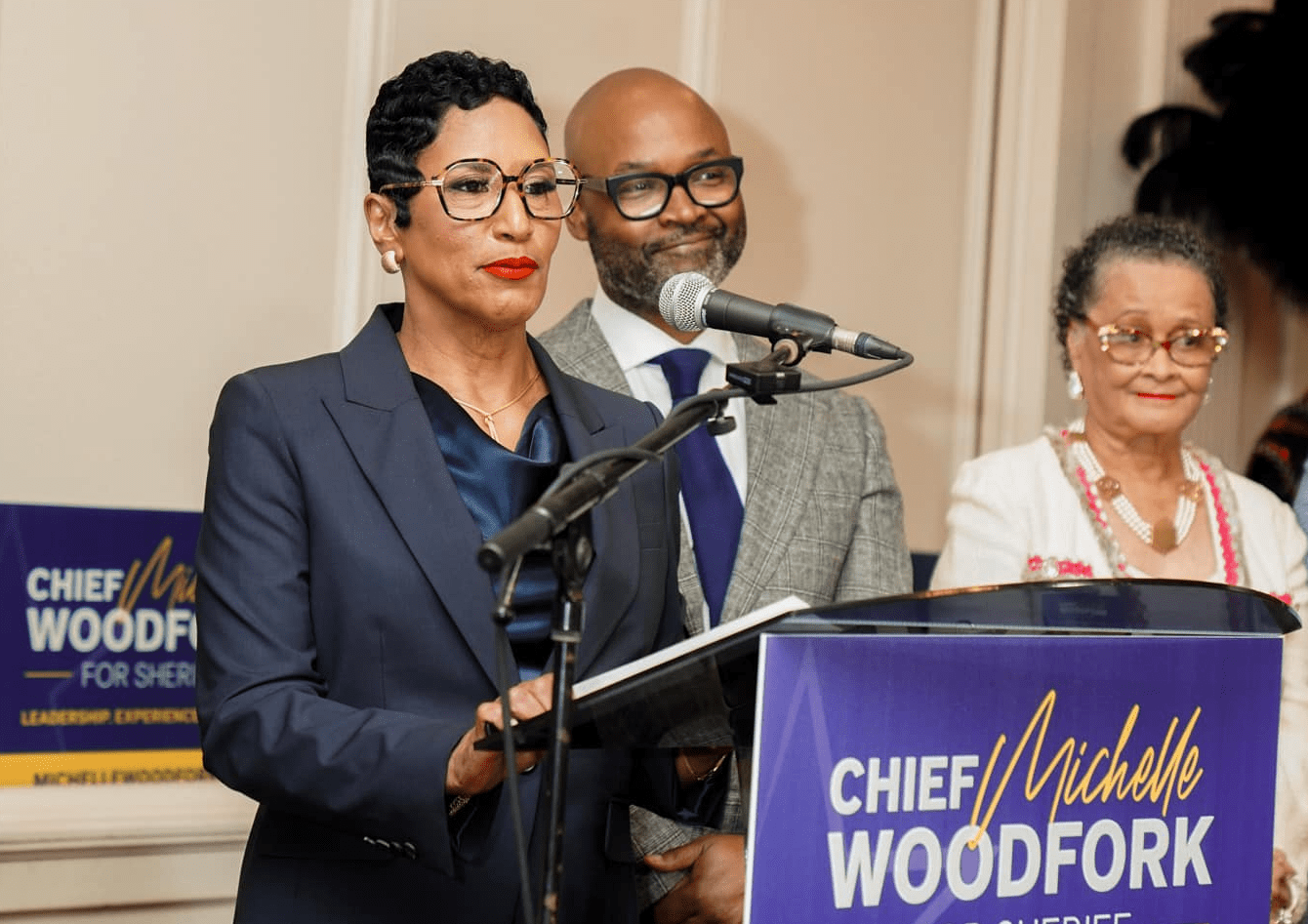

Michelle Woodfork unseated an outsider sheriff on Saturday, at a time when federal consent decrees barring ICE collaboration and lifting detention conditions may be ending.

| October 15, 2025

New Orleans voted on Saturday to change its sheriff at a fraught moment for law enforcement in the city. Michelle Woodfork easily unseated incumbent Susan Hutson, who came into the office four years ago as an outsider promising reforms but struggled to form robust alliances in New Orleans’ government and suffered intense fallout from a sensational jailbreak earlier this year.

Woodfork, a career law enforcement officer, spent much of her career at the New Orleans Police Department, including briefly serving as its interim superintendent, and currently serves as the director of forensic intelligence in the local district attorney’s office. She could preside over the end of a decade-long consent decree that has mandated federal oversight over the conditions at the troubled local jail, as well as the construction and rollout of a new psychiatric jail opposed by community advocates who are concerned that it will double down on treating mental illness as a carceral issue.

And she takes office at a moment of increased pressure on immigration enforcement from both the federal government and state leadership. Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill is hoping to force local cooperation with ICE and is seeking to terminate another consent decree that bars the New Orleans sheriff’s office from helping with immigration enforcement.

Woodfork, who is a Democrat like Hutson, says that she doesn’t want to take the office “backwards.” She shares Hutson’s preference for not assisting with immigration enforcement and says she’ll continue to implement the changes to jail conditions demanded by the federal court. Still, she expressed support to Bolts for ending the immigration consent decree, and local jail advocates have expressed some wariness about how she’ll run the office due to some of her campaign rhetoric.

Sign up to our newsletter

And learn more about sheriffs

In 2021, Hutson, an attorney who came from a police oversight background and had never worked in a sheriff’s department, ran an insurgent campaign against 17-year incumbent Marlin Gusman. Gusman had for years presided over a deadly and dysfunctional jail, leading to a damning DOJ investigation in 2012 and a federal consent decree aiming to improve conditions the following year. Hutson won on a progressive platform, pledging to support a reduced jail population, make detention conditions safer, and oppose the proposal for a new psychiatric facility, which was a change ordered by the judge presiding over the jail conditions consent decree.

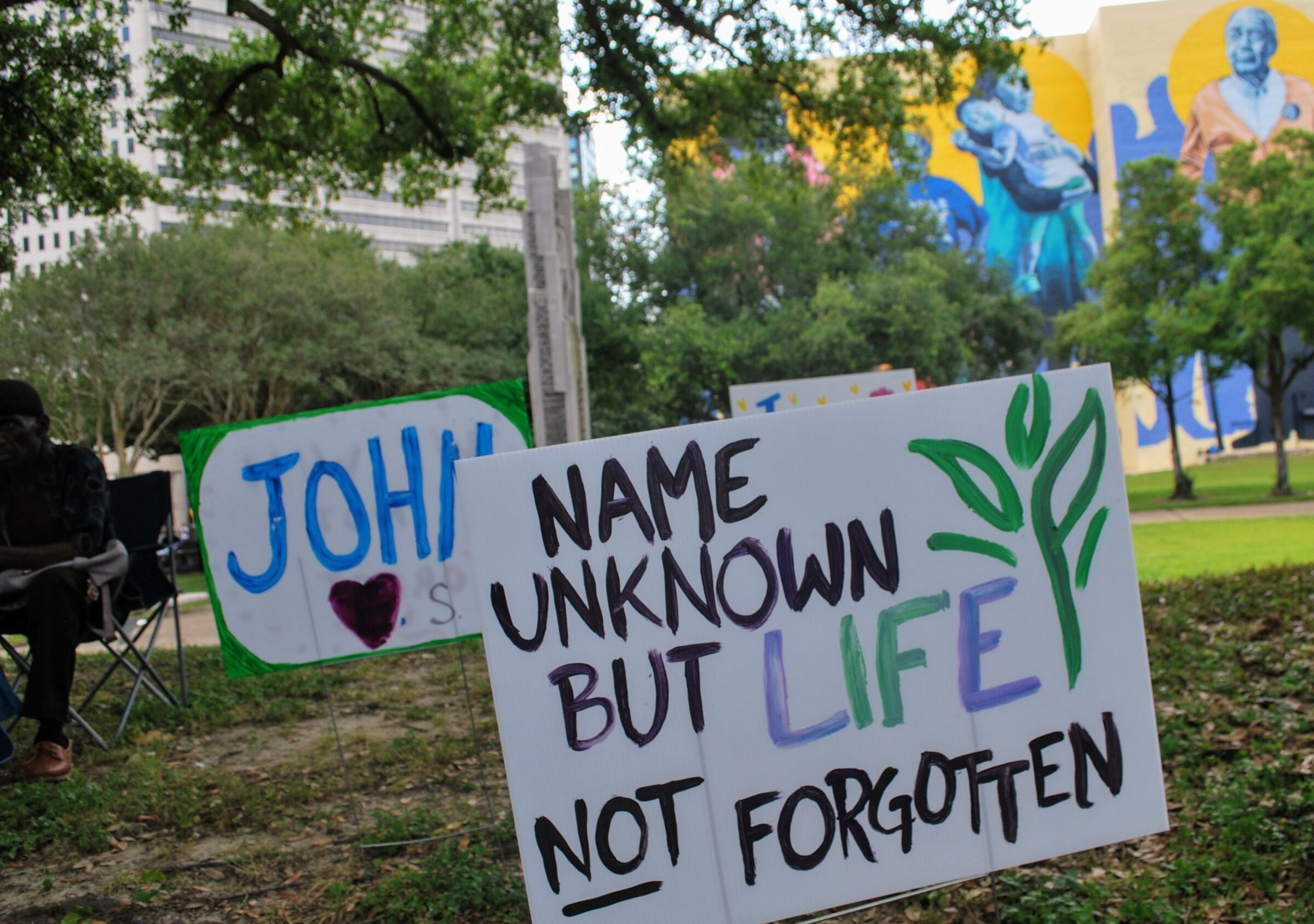

Jail deaths went down during Hutson’s time as sheriff: Five people have died during her four-year tenure, compared to 18 people over the prior eight years, according to data obtained by Andrea Armstrong, a law professor at Loyola University New Orleans who tracks jail deaths. Earlier on in Gusman’s tenure, before the consent decree, the death rate was considerably higher: six people died in 2007 alone, for instance. “The number one measure of success for me personally, is fewer people dying in that jail,” said Sade Dumas, former director of the Orleans Parish Prison Reform Coalition, who helped recruit and support Hutson in 2021.

Hutson also enacted other reforms to establish better treatment for those in her custody, such as instituting 15 minutes of free phone calls a day to fight against the exorbitant phone costs that incarcerated people face nationwide. She set up more options for mental health treatment, as well as a new program to provide medication-assisted opioid treatment to people.

But the jail remains plagued by violence, and Hutson struggled to secure the political alliances she needed to finance some of her initiatives, with the city council rejecting her bids for more funding. She also failed to convince a federal judge to stop the construction of the new psychiatric jail.

She split with a key early ally, Orleans Parish DA Jason Williams, who came in office on a reform platform himself in 2020 and then endorsed her challenge to Gusman in 2021. Williams this year supported Woodfork, who worked in his office.

Last year, the state forced Hutson to open a new unit to detain minors after a new law moved all 17-year olds to the adult system; Hutson spoke up against that law at the time.

The race this year was largely dominated by the May escape of 10 prisoners from Hutson’s jail, the last of whom was only recaptured two days before the election—a humiliating saga for the sheriff. Woodfork ran on making sure something like the jailbreak never happens again, framing it as the result of longstanding problems endemic to the facility and organizational culture.

Woodfork talked about needing to ensure proper levels of staffing and pledged to increase deputy recruitment. She highlighted her leadership role in the police department, which is also supervised by the federal government, as evidence that she’s best equipped to navigate oversight, telling Verité News, “I am the only candidate for Sheriff who has successfully advanced reforms under a federal consent decree.”

Local reform advocates are concerned that the escape will be used as a justification to undo reforms and implement more punitive measures in the jail. Woodfork told Bolts this wouldn’t be the case: “I’m absolutely not going to take it backwards.”

In an interview last month, Woodfork didn’t articulate clear policy differences from Hutson or the other four candidates in the race on how she’d manage the jail. She mentioned creating clearer disciplinary procedures for guards and establishing an internal affairs unit with expertise in investigations. “I don’t know what they have currently inside,” she said. (A Hutson advisor said the office “of course” has such a unit, which are standard in law enforcement agencies across the nation).

The jail conditions consent decree has been broadly unpopular, owing to the high costs and restrictions it has placed on local control, and advocates told Bolts they expect courts to phase it out. Woodfork told Bolts she wants out of the decree while keeping the reforms it outlines in place.

Dumas also supports ending the decree, in part due to her opposition to the psychiatric facility, but noted that she has concerns about regression without it. “It was a long fight to just get in that jail and figure out what was happening,” she said. “The biggest advantage was knowing what was happening on the inside, having more eyes on it, and having someone [to] whom the sheriff had to answer.”

Bruce Reilly, deputy director of Voice of the Experienced, or VOTE, a Louisiana justice reform organization run by formerly incarcerated people, told Bolts that a priority of his going forward will be to get the city to adopt an ordinance that’d establish a community oversight commission—as a mechanism to prevent backsliding once the consent decree ends.

The city government will be led next year by a new mayor, Helena Moreno, who is known as one of the more progressive members of the current city council. Moreno was critical of continued issues with jail conditions in the aftermath of the jailbreak.

The issue that most clearly distinguished Hutson from other candidates was immigration enforcement.

Since 2013, following the settlement of a lawsuit that alleged civil rights violations, the sheriff’s office has largely refused to detain people for ICE. This policy has put New Orleans at odds with law enforcement in the rest of Louisiana, which has rushed to help the Trump administration step up deportations.

This year, the state government adopted a law, Act 399, that requires local law enforcement to assist ICE and establishes criminal penalties for local officials who refuse. Hutson has maintained her department’s policies, saying she’ll do so as long as she is protected by the federal decree.

When Louisiana’s attorney general, Murrill, filed a legal motion in February to dissolve the consent decree, saying it was causing the “obstruction of lawful federal immigration enforcement,” Hutson responded in court that Murrill’s brief lacked factual basis.

Woodfork has said she wants to protect immigrants’ rights and ensure that the office “does not engage in blanket cooperation with ICE.” But in an interview with Bolts, she also said she wouldn’t fight to keep this consent decree in place. “I don’t have any problem getting out of the decree,” she said. “I’m going to commit to still putting some of those reforms, because I think they’re needed.”

When asked how she’d be able to maintain the restrictions on assisting ICE without the federal decree’s protections, given the state’s recent passage of Act 399, which mandates cooperation, Woodfork didn’t acknowledge any tension. She said, “Whatever the State law says, I have to adhere to it.”

Woodfork would not comment on whether she would consider a more affirmative form of collaboration with ICE, like the 287(g) program, which hands some of the authority of federal immigration agents to sheriffs deputies or police officers. Scores of Louisiana parishes have entered the program since Trump’s return to office.

“If the jail of New Orleans were to begin to collaborate with ICE, it would feel like a death sentence to immigrants in New Orleans based on what we’ve already seen happening,” Rachel Taber, an organizer with the New Orleans-based group Unión Migrante, told Bolts, citing rampant detentions and deportations in places like nearby Kenner, where the police department has a new 287(g) agreement.

Taber acknowledged that definitive statements on immigration could open Woodfork up to retaliation from state leadership, but urged her to sit down with immigrants’ rights groups. “I both understand why our next sheriff might be walking a fine political line, and yet immigrant advocates…need to be assured that our next sheriff is going to stand by these policies, and at least maintain them as long as we are able to,” she said.

Dumas noted that the federal government’s ramped-up immigration enforcement goals could dovetail with the new psychiatric facility, citing ICE’s frequent repurposing of other buildings as detention sites: “Once a carceral facility is built, there’s no control over what bodies are put there,” she said.

Back in 2021, when Hutson won, Dumas cheered the news but also warned that the movement to reduce Louisiana’s record level of incarceration wasn’t just about electing a single official, even if that official is a powerful sheriff. Four years later, she told Bolts, her feelings haven’t changed. “No one person can be our salvation,” she said. “We have to continue building power over years, over time—talking about the economic and moral impact of over incarceration and creating alternatives.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.