To Boost Turnout, Ballot Measure Proposes Moving New York City Elections to Even Years

When cities hold their local elections on off years, they tend to see terrible turnout. Many are rescheduling their contests when many more people go to the polls. Will New York be next?

| September 5, 2025

Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass had to win over a far larger electorate than her predecessors; more Angelenos took part in choosing their mayor in 2022 than in the two prior mayoral elections combined. San Francisco saw the same astounding growth last year, when more people voted in the city’s mayoral race than in its two prior regular elections combined.

Both cities owe this surge to the same reform, which moved their local contests from odd-numbered years to even-numbered years. Advocates for the change pointed to persistently low turnout for elections held on so-called off years, aiming to improve participation in their elections by syncing them to the presidential race or midterms.

“In even-numbered years, we’re just going to have more voters, more people paying attention, more resources put towards pamphlets and forums,” Alison Goh, who championed San Francisco’s reform as head of the local chapter of the League of Women Voters, told Bolts. “We want more people to be participating and having a direct say in who’s going to represent them.”

The nation’s most populous city may soon follow suit. On the New York City ballot this November, tucked far below the mayor’s race, voters are asked whether they want to change the timing of future municipal elections to even-numbered years.

The measure, which will appear on the ballot as Proposal 6, would align mayoral elections with the presidential race and reschedule contests for other offices like city council seats, which are up every two years.

Want updates on local elections?

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

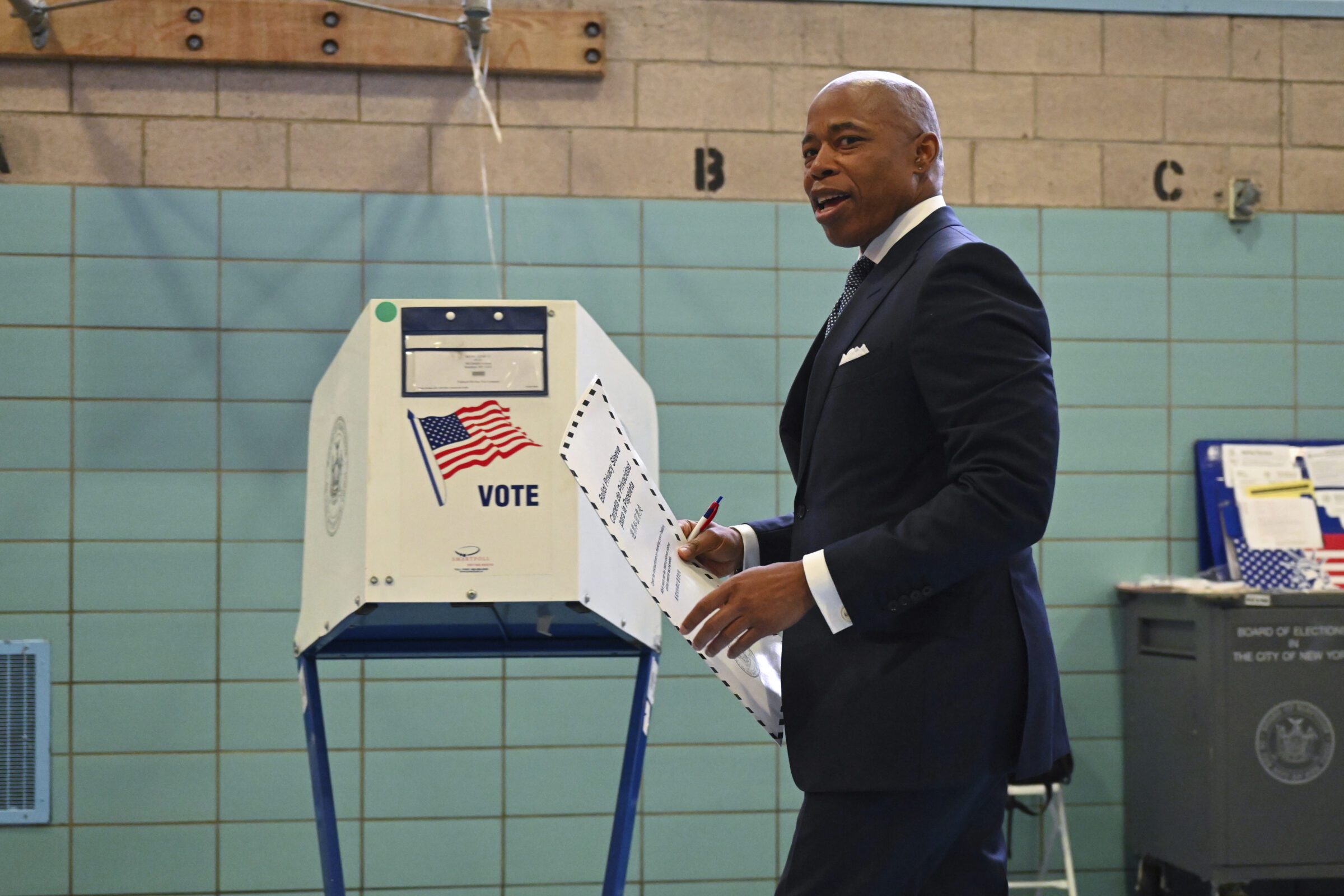

It was placed on the ballot by the city’s Charter Revision Commission, a 13-member body convened in December by Mayor Eric Adams to brainstorm possible changes. Empowered to review any issue, the commission largely focused on housing by advancing three controversial ballot measures meant to fast-track development projects. Another measure would instruct NYC to create a new, consolidated map of the city. Proposal 6 is the commission’s only measure that touches on how the city runs its elections.

Ben Weinberg, public policy director of Citizens Union, a New York-based group that has long pushed this reform, says the measure isn’t just about increasing the number of voters. “Holding local elections during even-numbered years will elevate local issues,” he says. “This is the time where folks are more tuned into electoral politics, the time where most people follow political news.”

After watching Los Angeles and San Francisco roll out this approach in recent years, plus a wave of other cities, Weinberg says he is now eager to bring the reform to New York City.

Even if voters approve Proposal 6, New York lawmakers would still need to amend the state’s constitution, which currently does not allow cities to hold their local elections on even-numbered years. And since constitutional amendments must pass in two consecutive legislative sessions, and then be ratified in a statewide referendum, that process takes at least two years.

But political will to reform this issue exists in Albany, where legislators have previously supported aligning local elections with national contests that generate higher turnout, passing a law in 2023 to reschedule local elections in New York’s towns and villages; that reform did not address city elections, since those require revising the constitution.

Senator James Skoufis, a Democrat who sponsored the 2023 law, has already introduced a constitutional amendment to realign city elections. He says he expects lawmakers will advance it next year if New York City voters pass Proposal 6 in November. “We want as many New Yorkers participating in local elections as possible,” Skoufis told Bolts. “When we have more people voting in these local races, the outcomes will be more reflective of the people that local leaders then serve, it’s as simple as that.”

Skoufis says it’s too early to know whether he’d want to push the legislature to place a constitutional amendment before voters in November 2027—the soonest the change could make it on the statewide ballot if New York City voters approve it this fall—or November 2028, which would delay the reform but set the statewide referendum during an even-year election that draws more voter participation.

But if the state’s voters were to ratify the change by 2027, Proposal 6 would kick in soon enough to change the timing of New York City’s next mayoral race, moving it from 2029 to 2028.

That means the mayor elected this November could potentially end up serving a term of just three years, instead of the usual four, before having to run for re-election.

The campaign of Democratic nominee Zohran Mamdani—the frontrunner for mayor this fall who, as a state Assemblymember, voted in favor of the 2023 law that rescheduled the state’s town and village elections—didn’t respond to requests for comment on his position on the referendum, nor did those of his opponents Andrew Cuomo, the former governor, or Adams, the current mayor. A spokesperson for James Walden, an independent candidate, said he supports the measure; a spokesperson for Republican nominee Curtis Sliwa said he opposes it.

If Proposal 6 and the state constitutional amendment end up passing fast enough to truncate the winner’s term, they’d get a major consolation prize: That term wouldn’t count for term-limit purposes (New York mayors can only serve two terms). If Mamdani or Cuomo win this fall and then end up serving only three years, for instance, they could still run in 2028 and 2032 and stay in City Hall for an additional eight years.

To many reformers who have called for this change, scheduling elections on off years—when it’s so obvious that turnout will be dramatically lower—amounts to voter suppression. They describe it as a way to gatekeep local democracy, leading to the selection of unrepresentative city leaders via an electorate that doesn’t look like the population as a whole.

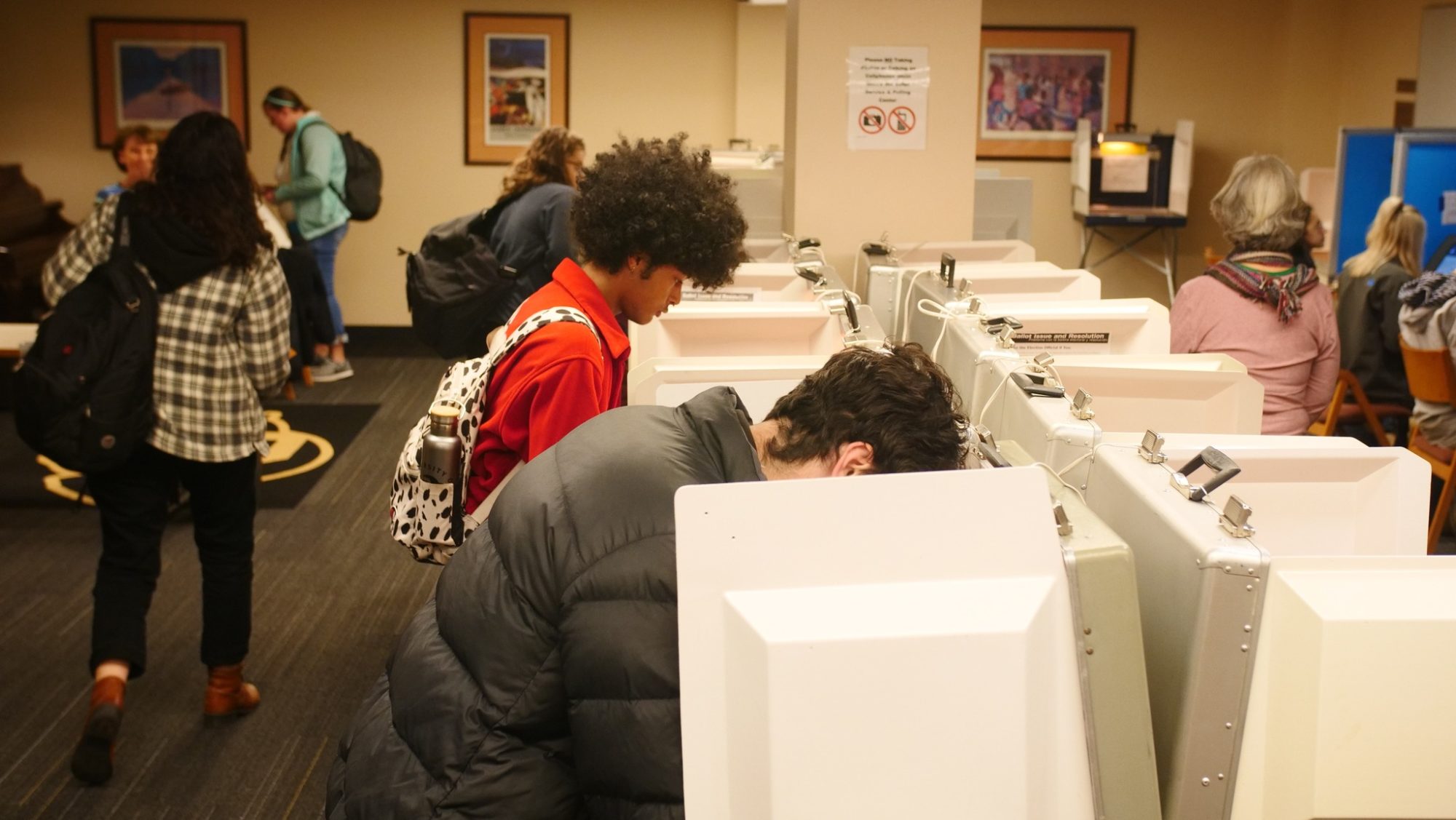

White voters, and higher-income and older voters, tend to be overrepresented in off-year elections, giving them outsized influence on local governments; meanwhile, turnout tends to drop disproportionately in lower-income areas and among voters of color compared to even-year elections. Local candidates who have run in odd-year elections have told Bolts that it’s challenging to campaign on policies that favor communities that are less likely to vote, such as housing policies that’d help renters.

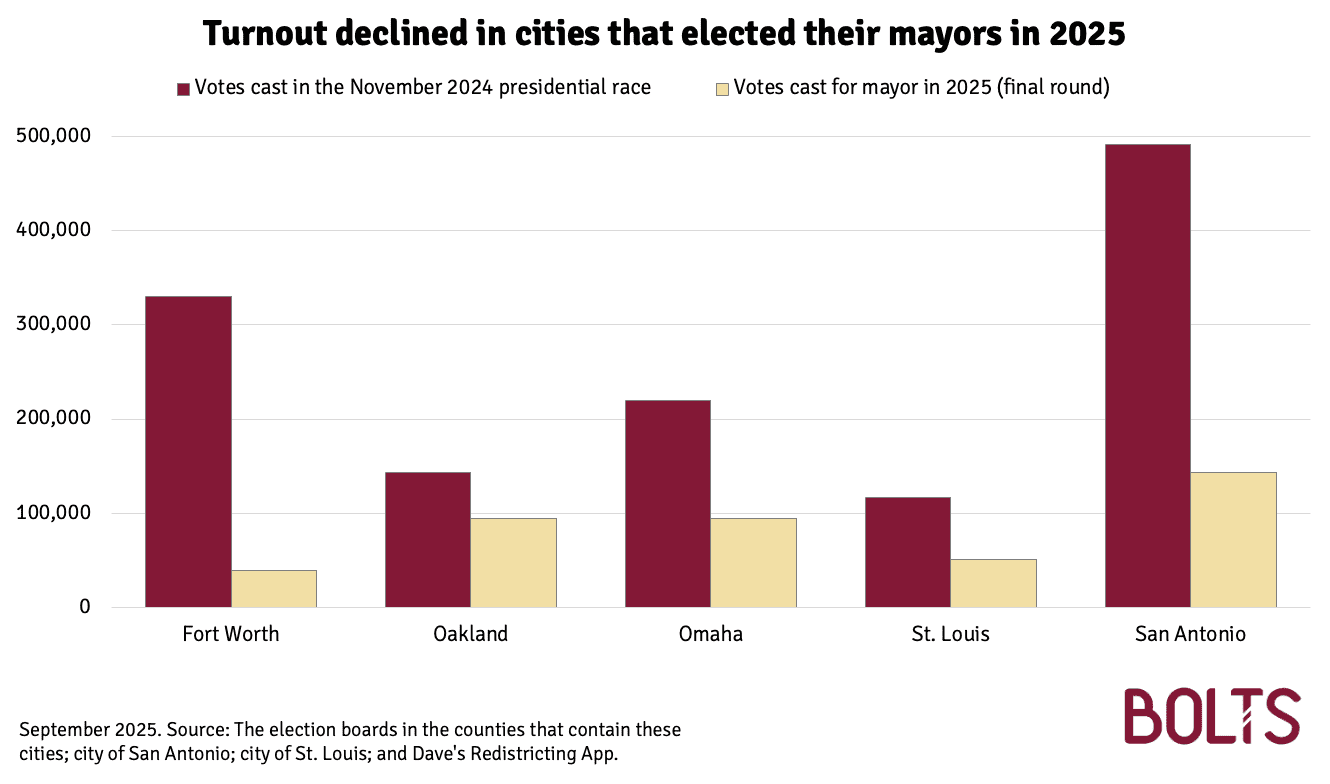

Bolts reviewed available data from the five cities of at least 250,000 residents that have elected their mayors in contested races so far in 2025, and predictably found that turnout cratered as compared to November 2024.

When Fort Worth elected its mayor in May, less than 10 percent of registered voters showed up, in line with past cycles. San Antonio’s expensive mayoral race in May saw 17 percent turnout, a drop of roughly 70 percent since last fall.

When the St. Louis and Omaha mayors were ousted this spring, the electorate was cut in half from 2024; turnout for those municipal races reached 26 percent and 32 percent, respectively. In Omaha, the biggest decline was in the city’s lower-income southeast corner. Similarly, in St. Louis, turnout dropped most in the poorer wards in North St. Louis, according to Bolts’ analysis.

In Oakland, the only city among the five that automatically mailed all voters a ballot, turnout reached 38 percent in April—down about 30 percent compared to the presidential election, though a smaller dropoff than in the other cities. Even then, less than one in five registered voters supported the winner, Barbara Lee.

Turnout declined throughout Oakland, but significantly more in parts of the city that have a higher share of Black and Latino voters.

New York City also sees greater disparities in voter turnout during off-year elections, compared to the major even-year cycles. According to a study that was commissioned by the city, disparities are especially pronounced between white and Hispanic voters. In 2021, turnout among white voters was five times higher than among Hispanic voters, whereas the gap was far less stark, though still significant, in recent presidential cycles, when white turnout was roughly twice as high.

A separate study, by the Harvard Law School Election Law Clinic, found a similar disparity by age.

“We know that youth turnout is especially bleak in New York City’s odd-year elections,” says Randy Frazer, executive director of YVote, a New York organization focused on youth engagement that supports the measure on New York’s 2025 ballot. “Youth voices are significantly underrepresented.”

Frazer says younger voters tend to gravitate toward the presidential race, and so syncing local contests with the presidential election will help teach them that all different levels of government matter. Much of his organization’s work involves “showing them the importance of local elections, and how much their voice matters at a local level,” he told Bolts. “Changing the cycle only strengthens the case.”

Opponents of scheduling local contests on higher-turnout, even-numbered years argue that the noise of more prominent federal or statewide campaigns will distract from local stakes and races—leading, they say, to less informed voters.

In 2023, when New York adopted the state law rescheduling town and village elections, the New York State Association of Counties, or NYSAC, strongly opposed the change. “The critical issues that actually impact New Yorkers daily lives will get drowned out by the mudslinging of national and state politics,” Albany County Executive Daniel McCoy, a Democrat who served as the NYSAC president, said at the time. “The residents of our communities deserve better. They deserve to hear substantive debate about the issues that matter.”

NYSAC also argued that the 2023 legislation was illegal because the state was mandating that localities change their election schedules, which critics of the law said violated the state’s home rule provisions. (State Republicans sued on those grounds and got a judge to strike down the law, but that decision was overturned by an appeals court in May.) In an interview this week, NYSAC executive director Stephen Acquario told Bolts that New York City is going about it the proper way by asking city voters to make the decision themselves. “We believe that’s the correct path,” he said.

On the merits, Acquario said neither he nor NYSAC have taken a formal position on New York City’s ballot measure, but added that he still worries about the effects it could have. “We hear concerns that it buries the local issues versus the national issues” he said. “Affordability, housing, food insecurity, public safety, gun violence, drug epidemic—those are concerns locally in the city of New York, and if you tie it up with other concerns of international issues, you could wash away local issues.”

Skoufis, the lawmaker who sponsored the legislation to realign more local elections, rejects the criticism that changing the timing of local elections will prove confusing, calling the idea “insulting to voters” in an interview with Bolts. “I happen to have more faith in voters, and believe that they are capable and intelligent enough to be able to discern the differences between voting for mayor and voting for president, and making judgment calls in each,” he said.

Weinberg, the Citizens Union policy director and a leading proponent of this reform, told Bolts it’s dangerous to reject a system where many more people vote based on assumptions about how informed those people are.“We don’t qualify the rights of voters based on their knowledge or familiarity with issues or candidates or officials, thank God,” he said.

Even if Proposal 6 passes this November and is later implemented, that won’t necessarily mean that elections with the highest turnout determine local races.

In this overwhelmingly blue city, most municipal elections would continue to be decided in summertime Democratic primaries, which see much lower turnout than November general elections, especially in presidential cycles.

Some cities that have boosted turnout for municipal elections by moving them to even years have also eliminated primaries entirely: San Francisco, which passed a ballot measure in 2022 that aligned its municipal races with the presidential cycle, uses a one-round system with ranked-choice voting—so that the city picks its leaders during the election with the highest possible turnout. (New York City uses ranked-choice voting as well, but only to decide the results of primaries.)

Some voting advocates had hoped NYC officials would advance a proposal to adopt so-called open primaries, which would allow all registered voters to participate in the primary of their choice.

Currently, only voters who are registered as Democrats can participate in the city’s Democratic primaries. Young New Yorkers are more likely to not be registered with a political party, meaning they are disproportionately kept out of the city’s closed primaries.

The city’s Charter Revision Commission said in a report that throughout its public hearings, it “heard more testimony on open primaries than any other subject.” While the commission concluded that “the need to reform the closed primary system is crystal clear,” it declined to propose a ballot measure changing to open primaries this year, but recommended a future commission explore the issue further ahead of the next municipal election cycle.

The commission also noted that “this year, with hotly contested local elections on the ballot, may create an inhospitable climate for discussion about an election reform of this magnitude.”

Weinberg says he’ll keep advocating for open primaries in the future, telling Bolts, “We should not continue to exclude over one million unaffiliated voters, who are shut out of our closed primary system, from this critical stage of the electoral process.”

Editor’s note: This ballot measure was initially known as Question 5 when the commission advanced it. This story was updated in late September to reflect the fact that it will appear on the ballot as Proposal 6.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.