North Carolina’s Two Largest Counties Quit ICE Program. Will a Third Follow?

Two large North Carolina counties quit ICE's 287(g) program this month.

December 13, 2018

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

This article is part of a series on 287(g) contracts in states.

ICE’s prized 287(g) program took a hit last week. Two of the nation’s four largest counties with 287(g) contracts quit the program within days of one another; both are North Carolina counties that encompass more than one million residents each.

Gerald Baker and Garry McFadden promised to curtail cooperation with ICE in their successful bids against the sheriffs of Wake County (Raleigh) and Mecklenburg County (Charlotte) this year. And both terminated their counties’ 287(g) contracts shortly after entering office.

The contracts authorize local law enforcement to research the immigration status of people brought to the county jail. Mecklenburg and Wake’s participation led thousands to be deported over the last decade. Its proponents argue that these deportations improve public safety; Wake County’s departing sheriff, Donnie Harrison, described 287(g) as “a valuable tool that has identified some very dangerous individuals.” But Harrison’s participation meant that he was alerting ICE of people who were not yet convicted and who faced minor allegations.

According to Indy Week, one of the last individuals to face deportation in Wake because of 287(g) is a man named Coronilla Loyola who was arrested in November for driving without a license. Harrison’s policies shaped the very circumstances of Loyola’s arrest since Harrison rejected demands by immigrant rights’ activists that he support legislation enabling undocumented people to get driver’s licenses or that he recognize alternative forms of identification.

In addition, Durham County’s new sheriff, Clarence Birkhead, announced that he would stop honoring ICE requests to continue detaining individuals beyond their scheduled release. (Durham was already not part of 287(g).) Birkhead ousted Sheriff Mike Andrews, who defended such detainers, in the Democratic primary in May.

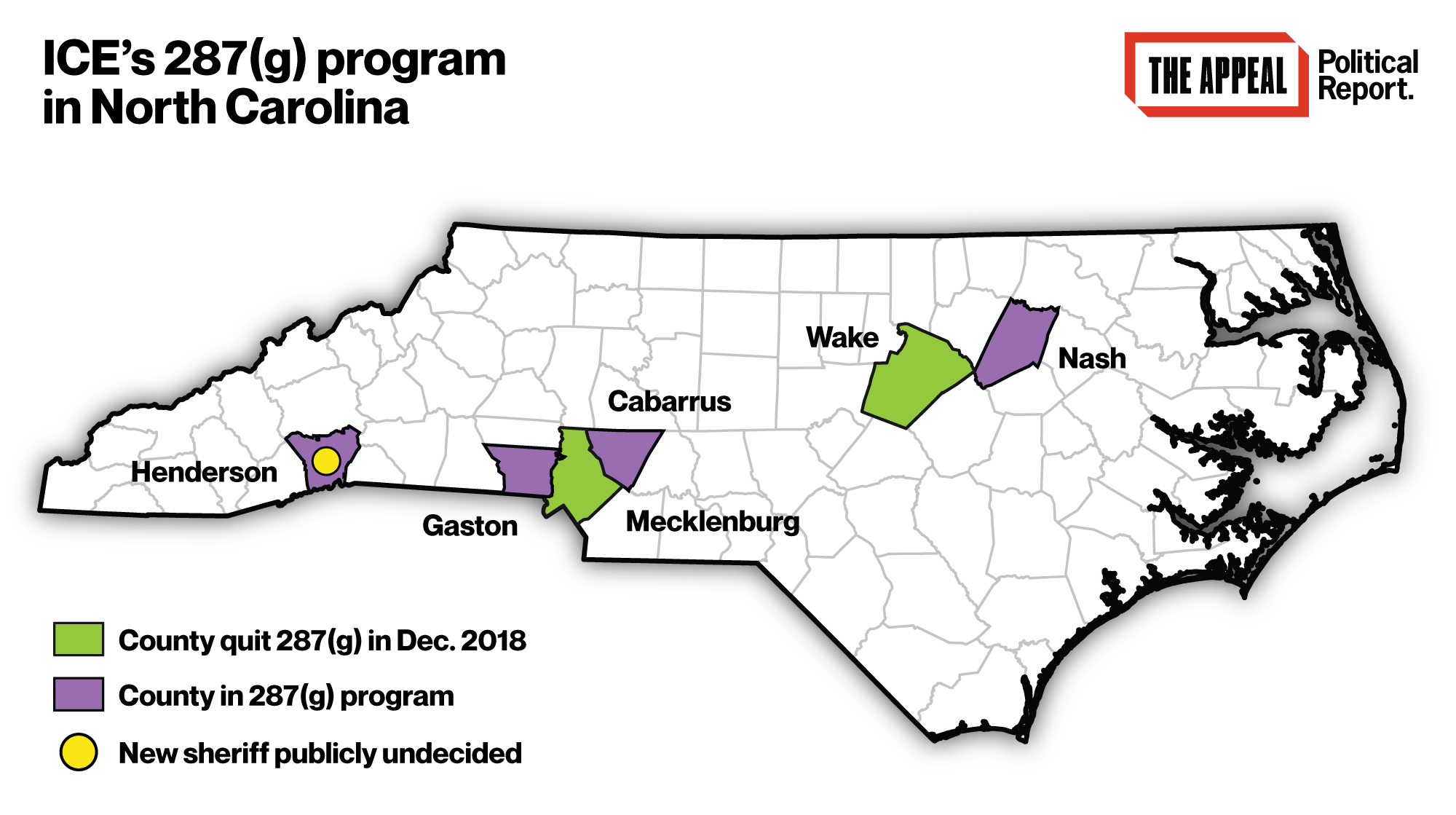

Mecklenburg and Wake’s departures leave four North Carolina counties in the 287(g) program.

One of these four, Henderson County, has a new sheriff who is publicly undecided about whether to remain in 287(g). Lawrence Griffin ousted Sheriff Charlie McDonald in the Republican primary, which took place right after high-profile ICE raids. Griffin expressed ambivalence toward 287(g) during the campaign. “I am going to have to look into [287(g)] in detail,” he told WLOS in May. “We have a lot of folks in this area that have come here looking for a better way of life. They are paramount to the economy of Henderson County as a whole, so I don’t want to use it as a punitive measure to intimidate anyone in the county.” Griffin indicated in November that he was still undecided and he pointed to the current contract’s June 30 expiration as a horizon for his decision. The immigrants’ rights groups Compañeros Inmigrantes de las Montañas en Acción and El Centro have been active in demanding change, and First Congregational United Church of Christ in Hendersonville launched a petition for the county to quit 287(g).

Cabarrus County is yet another 287(g) county with a new sheriff. Cabarrus joined the program in 2008 under the direction of Democratic Sheriff Brad Riley, who retired this year and endorsed Republican Van Shaw, the eventual victor. I found no public statements from Shaw about 287(g), and his office did not answer requests for comment regarding his position toward it.

The sheriffs responsible for 287(g) contracts in the remaining counties are still in office. Both secured new four-year terms in November. In Gaston County, Democratic Sheriff Alan Cloninger joined 287(g) in 2007, and his website boasts of the deportations that the program has enabled. In Nash County, Republican Sheriff Keith Stone joined 287(g) in March of this year. Despite the fact that this county is politically competitive, Stone secured a second term without facing a single opponent in either the primary or general election.

Immigrant rights’ organizers also scored a win in Alamance County, where Sheriff Terry Johnson dropped his application to rejoin the 287(g) program in November. The Obama administration terminated Alamance’s contract in 2012 after a Department of Justice investigation alleged discrimination and racial profiling by Johnson and his deputies.

Groups including Siembra NC and Down Home NC organized numerous protests against Johnson’s bid for a new 287(g) contract this year. Andrew Willis Garces, the organizing coordinator for American Friends Service Committee, the group that launched Siembra NC, told me that this local mobilization was crucial to the sheriff’s decision to back down. “They’ve seen the level of opposition,” he told me. “It’s literally been evident on street corners. That has everything to do with it. This has been an unprecedented year of organizing, with different kinds of people who are not the usual suspects coming out against family separation locally. That is very inspiring.”

However, Johnson is still looking to reinstate a contract to house ICE detainees in exchange for payments. The 287(g) decision “is a victory in the sense that there will not be county employees doing ICE’s job, but there will still be ICE employees nearby,” Garces said of this other potential deal. “It’s still going to undermine public safety.”