On His Way Out, North Carolina Governor Expands Support for People Leaving Prison

An executive order directs state agencies to improve reentry services and fix a broken system that failed me and thousands of others released from prison into homelessness each year.

| July 17, 2024

After I served 14 months in prison for petty crimes, the state of North Carolina released me into homelessness on Dec. 30, 2000 with only the prison clothes on my back, a paper identification card, and $3.36 in my pocket. Rebuilding my life wasn’t my primary focus. I needed food and a warm place to sleep. On my first night of freedom, a friend who still lived with his parents snuck me in to sleep on his bedroom floor. His mother found me the next morning and made me leave. Alone, I trekked miles through the frigid cold wearing a borrowed jacket and boots, desperately seeking another place of refuge.

Desperation defined my reentry to society as I struggled to find stability. Obtaining necessary items, like a state identification card through the Department of Motor Vehicles, proved nearly impossible because I’d left prison without a social security card, which I applied for after release. Weeks passed before it arrived at a friend’s house by mail, preventing me from working during that time. I relied on friends to feed me because I could not work to feed myself. After a string of poor decisions and a drug deal gone bad, I was arrested for murder—just 60 days post-release. A jury sentenced me to life without parole at the age of 24. I have always taken responsibility for my actions; however, I wouldn’t be here if I had been offered reentry assistance—shelter, clothes, and food—upon release from prison.

Thousands have left prison as hopelessly as I did in recent decades. According to reporting by NC Newsline, around 3,000 of the roughly 18,000 people who left North Carolina prisons in 2023 were homeless—that’s about one in six people.

How many recidivists could have remained free if more schools had been available in prison, if they had left prison with a state ID, or if they had been guaranteed a place to sleep their first night out? People need help to survive after prison. I needed help.

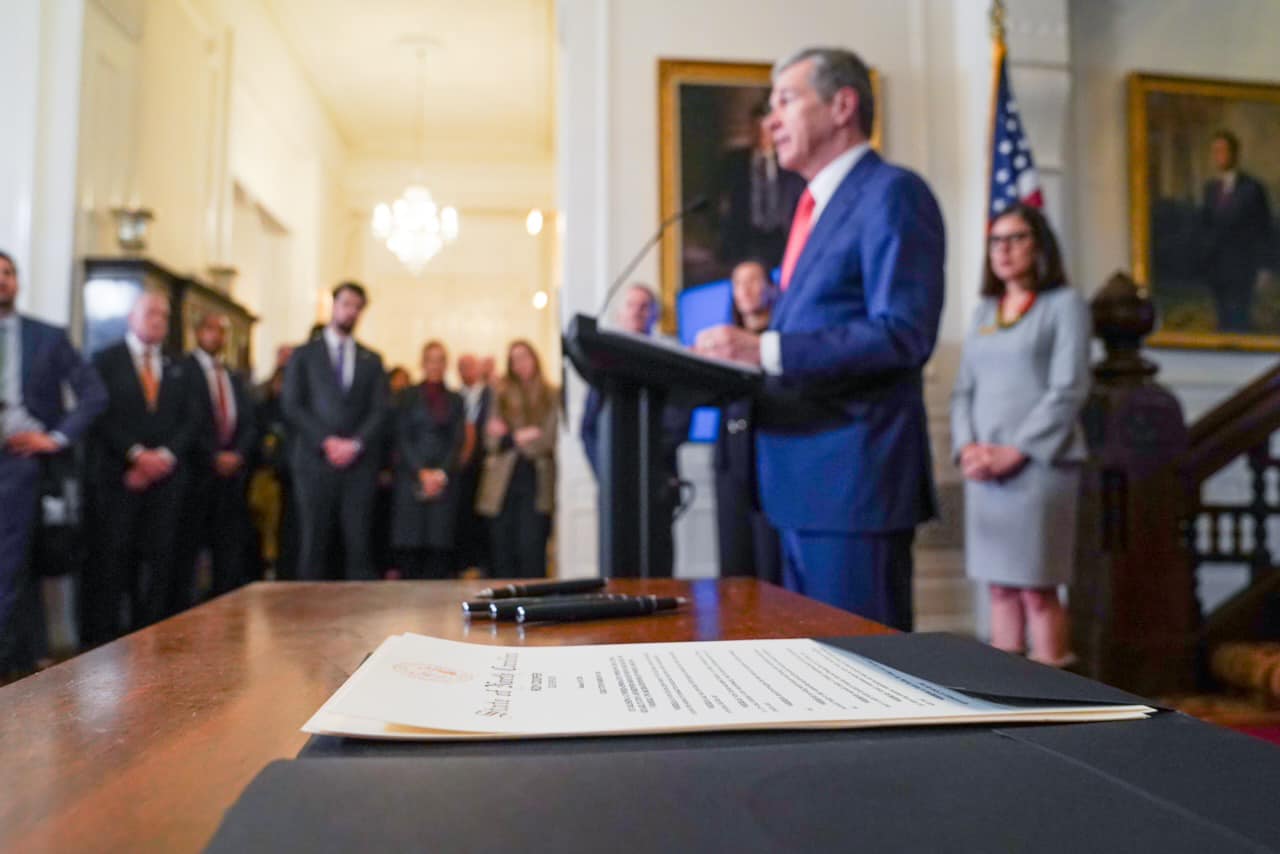

This year, North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper took steps to fix this broken system that failed me years ago. On Jan. 29, Cooper issued an executive order directing the North Carolina Department of Adult Correction (DAC) to lead a coordinated effort with all state cabinet agencies to improve reentry services.

“This is not only the right thing to do, this is the smart thing to do,” Cooper said in a press conference after signing the order. “Our state’s correctional facilities are a hidden source of talent: People with diverse experiences and skills who really want to change their lives.”

Among the list of directives to state agencies, Cooper’s order tasked the Department of Health and Human Services with helping connect returning citizens to Medicaid, food assistance and other government services as they prepare for release. The order also directs the state Department of Transportation to increase availability of state ID cards to people preparing for release and expand work release and other employment opportunities to incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people.

His order also directs the DAC to “increase access to and completion of educational programs in state correctional facilities” and help incarcerated people “communicate with justice system partners to resolve outstanding warrants, tickets, investigations, obstacles to driver’s license restoration, and other unresolved legal issues prior to release.”

Cooper’s directive made North Carolina one of four states to join Reentry 2030, a national initiative spearheaded by The Council of State Governments Justice Center to improve access to resources for newly released people and remove barriers that lead to recidivism. Missouri, Alabama, and Nebraska have also adopted the initiative, which asks states to set specific goals to improve reentry.

When Cooper issued his order in January, he listed a series of benchmarks that he wants North Carolina to hit by the end of the decade—such as increasing the number of incarcerated students earning high school and post-secondary degrees by 75 percent, and reducing the number of people released from prison into homelessness by 50 percent.

When I was released in 2000, reentry services in North Carolina had been stymied by the repeal of parole in 1994. The state’s new mandatory minimum sentencing scheme did not require post-release supervision. When a prison sentence ended, the state released most prisoners without ensuring they had means of survival, such as housing.

To address deficiencies in reentry, the North Carolina legislature passed The Justice Reinvestment Act in 2011, which mandated that people with felony convictions serve the final nine to twelve months of their prison sentence on post-release monitoring out in the community. However, unlike parole, this new post-release mechanism did not require a showing of rehabilitation before early release, nor did it incorporate more reentry services to curb recidivism; measures under the Justice Reinvestment Act only ensured that newly-released people would be monitored.

Brian Scott, executive director of the North Carolina-based reentry nonprofit Our Journey, attended the signing of Cooper’s executive order at the governor’s mansion earlier this year. Scott, who was released in 2021 after serving 20 years in prison, applauded Cooper’s effort to improve reentry services. But he also raised concerns about how much it might actually change.

The governor’s executive order, set to expire at the end of 2030, earmarks no new funding to improve reentry services, and could end if a new governor opposes it; Cooper, a Democrat who is term-limited from running again, will be replaced next year by whoever wins this November’s competitive governor election.

“It’s an executive order, not legislation, which means that while it reflects Governor Cooper’s priorities, it might not for the next governor who takes office in 2025,” Scott told me in a text message. “Until [Cooper] can get the North Carolina General Assembly to fund it, not everything can move forward. But this is still a very significant moment.”

Cooper’s order established a statewide reentry council composed of staffers from each cabinet agency who have been tasked with devising a plan on how to improve reentry. That plan, according to the order, should lay out strategies and metrics for agencies to improve economic mobility for people leaving prison, expand access to behavioral health and substance abuse services before and after release, and increase housing opportunities for formerly incarcerated people.

The council is supposed to release its recommendations by the end of July. That will leave a short window for the governor’s office to move forward before the end of Cooper’s term.

Kristie Puckett, senior project manager for Forward Justice, an advocacy group that advocates for racial and economic justice in the South, told me she believes that Cooper issued the order too late in his tenure.

“It’s political,” Puckett said in a phone interview, noting that reform advocates have been asking for provisions in this year’s executive order for at least a decade. “He’s been in office for eight years. He could have directed his cabinet to do this long ago. That’s not progress. It can be repealed as quickly as he signed it … It moves the needle closer to where we need it, but we want real legislation that will last, not a temporary executive order.”

Cooper’s order expands on some steps the state has already taken to improve reentry in recent years. The statewide expansion of Medicaid in 2023 extended those services to newly-released people. Last year, the state DMV and prison system also started working together to issue state IDs to incarcerated people slated for release who expressed interest in obtaining them, however there remained limitations. It’s unclear what additional features of Cooper’s order can move forward or when without more funding.

Puckett says the biggest benefit from the reentry order could wind up being data from studies that the new statewide reentry council is supposed to conduct on the current state of services for people leaving North Carolina prisons. “We want to know what programs are available. How do incarcerated people access them? How often? What is the white versus Black ratio for successful reentry programs? We can use that data to trace harmful and helpful trends,” Puckett said.

If North Carolina had prioritized reentry assistance when I left prison in 2000, it is likely I wouldn’t be serving a life sentence today. No one wants to return to prison, but desperation after release can activate the revolving door by compelling someone to rely on crime for survival. A state sentencing commission report in 2022 estimated that 36 percent of people released from North Carolina prisons are re-incarcerated within two years.

Even if it’s too late for me, Cooper acknowledged in his executive order that giving more people a fresh start after prison could improve public safety, saying that “successful reentry of formerly incarcerated people into their communities leads to a safer North Carolina by reducing crime and breaking the cycle of violence.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.