Ohioans Reject Redistricting Reform, Protecting GOP Gerrymanders

After legal battles over the wording of the ballot language, Issue 1 lost on Tuesday. It would have created an independent redistricting commission.

| November 5, 2024

Ohioans on Tuesday rejected Issue 1, a ballot measure that would have created a new independent redistricting commission and stripped elected politicians of their power to draw congressional and legislative districts.

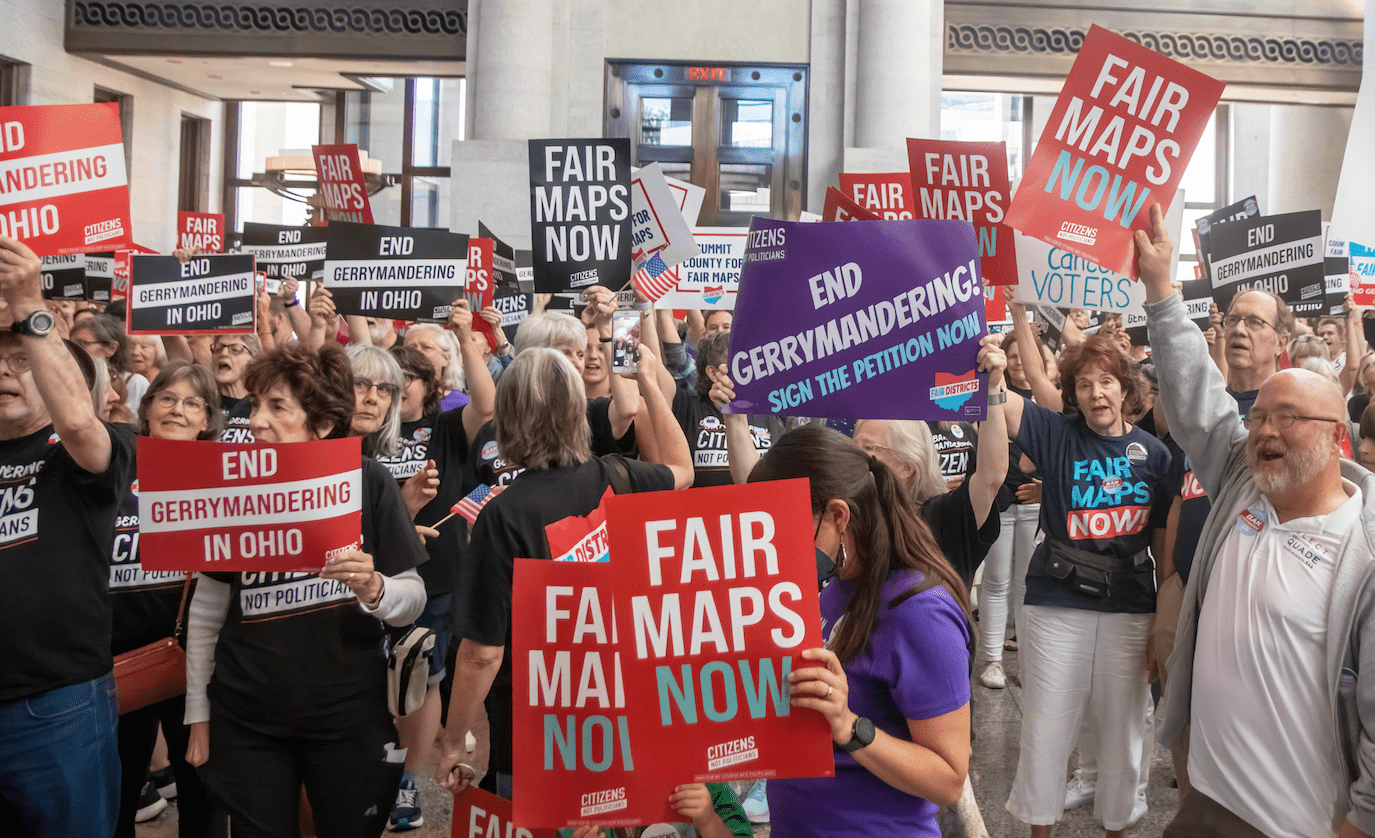

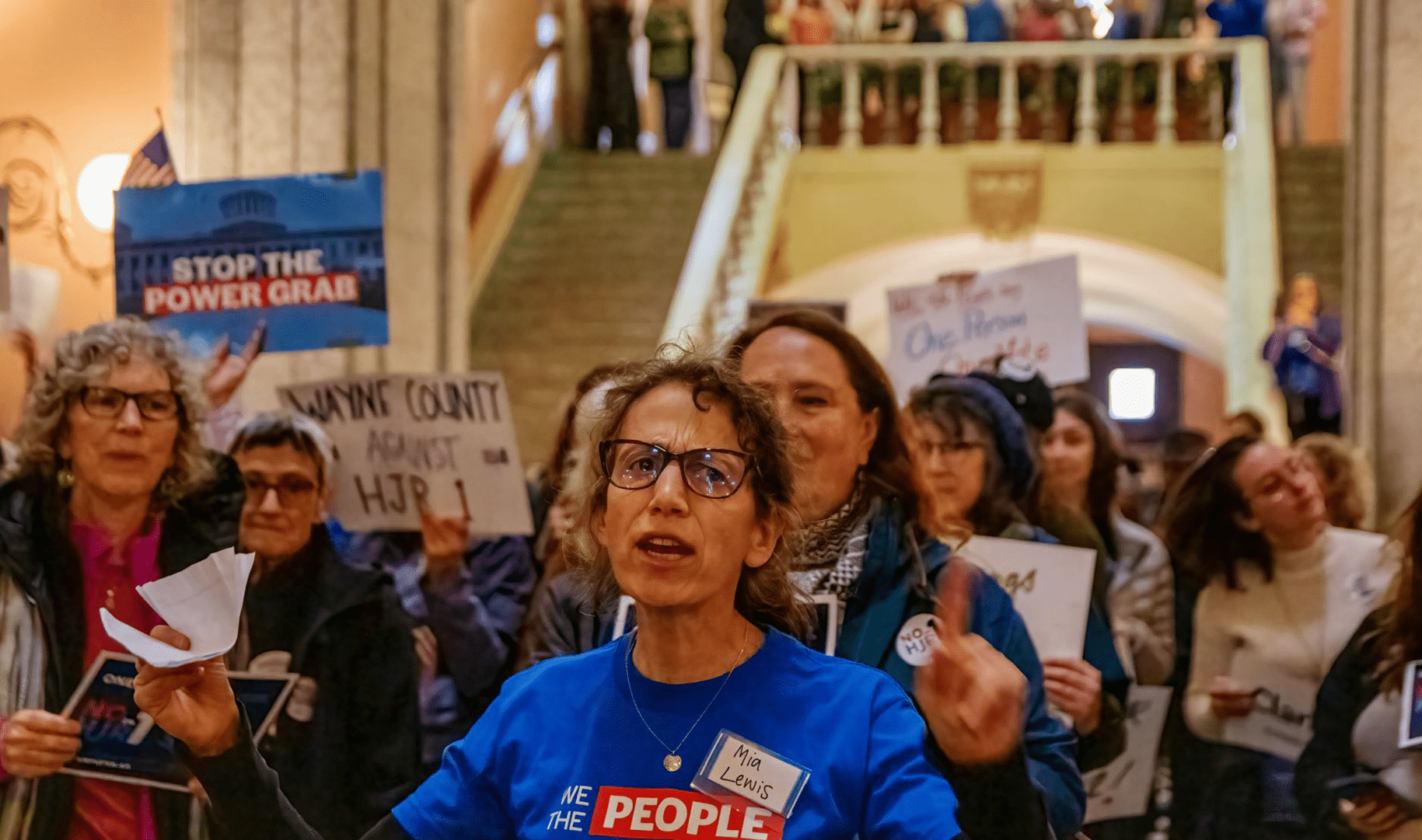

The result is a blow to the democracy organizations that have been combating gerrymandering in the state. They mobilized on behalf of Issue 1 after the lengthy legal standoff with Ohio Republicans in 2022, when the GOP, in a repeat of the prior decade, drew maps that locked in comfortable majorities for their candidates.

It’s also a repeat of two prior defeats for similar ballot measures that would have created independent commissions in both 2005 and 2012.

“It’s incredibly sad, and it’s not clear to me what the next steps are to improve our democracy,” said Catherine Turcer, executive director of Common Cause, an organization that was part of the coalition that collected hundreds of thousands of signatures that qualify Issue 1 for the ballot. “Addressing gerrymandering is so much about holding elected officials accountable and creating fair districts and fair elections so that we can actually have a functional government.”

As of publication, the measure is trailing by roughly eight percentage points, with some ballots remaining to be counted.

While several polls in October showed Issue 1 with very large leads, those surveys were simply asking voters if they wanted to create an independent redistricting commission. The official language Ohioans saw on their ballot was very different: GOP officials wrote an official summary that characterized the measure as requiring gerrymandering rather than restricting it. A rare poll that tested the official language found the race effectively tied.

Voters came forward during the early voting period in October to warn that they felt tricked by the GOP-crafted summary. Songgu Kwon, a comic book writer living near Athens, told Bolts that he meant to support the independent redistricting commission but mistakenly voted against Issue 1 after feeling confused in the voting booth. “I didn’t think that they would go so far as to just straight up lie and use a word that means one thing to describe something else,” he said.

Other media outlets reported similar complaints from other voters who said they only realized after voting ‘no’ that they had meant to vote ‘yes.’ Turcer attributes Issue 1’s failure to the “incredibly deceptive ballot language,” telling Bolts, “elected officials were willing to do anything to stop Issue 1.”

Opponents of Issue 1 defended the ballot language, with Secretary of State Frank LaRose, a Republican who drafted much of it, calling it an “honest explanation.” A spokesperson for Ohio Works, the committee that promoted the ‘no’ vote, said that, “If people go in and intend to vote for Issue 1, read the ballot language and vote no, they are not confused.”

Issue 1 prevailed in Ohio’s urban centers, which are also the regions whose power the GOP’s gerrymanders have undercut, but it trailed in the more exurban and rural areas.

Ohioans on the same day voted for Donald Trump for president, and the county-level results for Issue 1 broadly correlate with the presidential results, with more Republican areas opposing the proposed reform.

Aware that they had to persuade Ohioans who vote Republican in this red-leaning state, the ‘yes’ campaign made the case that stopping gerrymandering should not be a partisan issue.

“When you have a gerrymandered state, whether it’s Republicans or Democrats doing the gerrymandering, what you end up with is legislators who are not responsive to the citizens, and you end up with bad public policy, and it just holds your state back,” Chris Davey, a spokesperson for Citizens Not Politicians, the campaign for Issue 1, told Bolts.

One of the measure’s chief proponents was Maureen O’Connor, Ohio’s former Republican chief justice. O’Connor joined her Democratic colleagues on the state supreme court two years ago to strike down Republican-drawn maps seven separate times, but the GOP leaders ran out the clock until O’Connor retired in December of 2022 and her Republican replacement blessed gerrymanders. O’Connor also featured in advertising for Issue 1 this fall, telling voters that the measure “will restore power to where it belongs—with citizens, not politicians.”

But the state’s Republican leaders, including Governor Mike DeWine, rallied against Issue 1. The ‘no’ campaign appealed to Ohio’s overall red lean, making the case that the measure boiled down to an attempt by the Democratic Party to expand its influence on the state. “Don’t let Democrats rewrite the rules,” one ad for the ‘no’ campaign stated. “Protect Ohio’s voice!”

The ‘no’ campaign also emulated the ballot language in trying to turn the table on Issue 1, with yard signs and other messaging that proclaimed that a ‘no’ vote would “stop gerrymandering.” Opponents of Issue 1 made the case that it would erase constitutional protections against unfair maps that Ohioans approved in a 2015 referendum, but reform advocates complained that the Republican mapmakers basically ignored those criteria when they last redrew districts in 2022.

Issue 1 would have set up a new, 15-member panel made up of citizens selected from a pool of applicants; the body, tasked with redrawing the state’s maps, would have included five registered Republicans, five registered Democrats, and five people who are neither.

This system would have broadly resembled similar commissions set up in states like Arizona, California, and Michigan, which adopted new redistricting processes through successful ballot initiatives. Most recently, in 2018, Michigan voters approved a constitutional amendment that set up an independent redistricting commission by an overwhelming majority, with 61 percent of the vote.

Instead, the failure of Ohio’s measure protects the status quo, which grants the authority to draw districts to a panel of elected officials, including the governor and secretary of state, plus appointees of legislative leaders.

Going into Tuesday, Ohio’s congressional delegation has 10 Republicans and 5 Democrats. The state House is made up of 67 Republicans and 32 Democrats. And the state Senate is made up of 26 Republicans and 7 Democrats.

These splits mask a deeper asymmetry in the current congressional map: All 10 of the GOP-held congressional districts are considered to be safely Republican, meaning that they pack so many voters who reliably vote for the GOP that Democrats are not expected to be able to compete there. By contrast, three of the five Democratic-held districts are competitive and winnable by the GOP. In fact, Democrats may lose one of the seats they hold on Tuesday, as the 9th District remains too close as of publication.

Issue 1 included a requirement that the state’s congressional and legislative maps closely mirror Ohio’s statewide partisan split. It likely would have resulted in maps that included at least one additional Democratic-leaning congressional seat, and at least a dozen additional Democratic-leaning legislative seats. This would not have guaranteed how each district votes on any election day, but it would have likely changed the composition of the legislature and House delegation.

Turcer, of Common Cause, said she is not sure yet what comes next for her and other anti-gerrymandering advocates. “We need to regroup and figure out how we’re actually going to get the job done,” she said. “What I do know is that it is going to take time and effort, and we’re gonna have to be really thoughtful and strategic, and that means it’ll take time to figure out what our next steps are.”

But she also stressed she is determined to find a way to constrain gerrymandering to ensure that voters’ partisan preferences are better reflected in Congress and the legislature. “Their goal is to maximize their power, not to actually create fair elections,” she said of the state’s elected officials.

She added, “We all want to participate in meaningful elections. We don’t want to participate in theater.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.