The Republican Nominee to Lead Oregon Elections Wants to Stop All Mail Voting

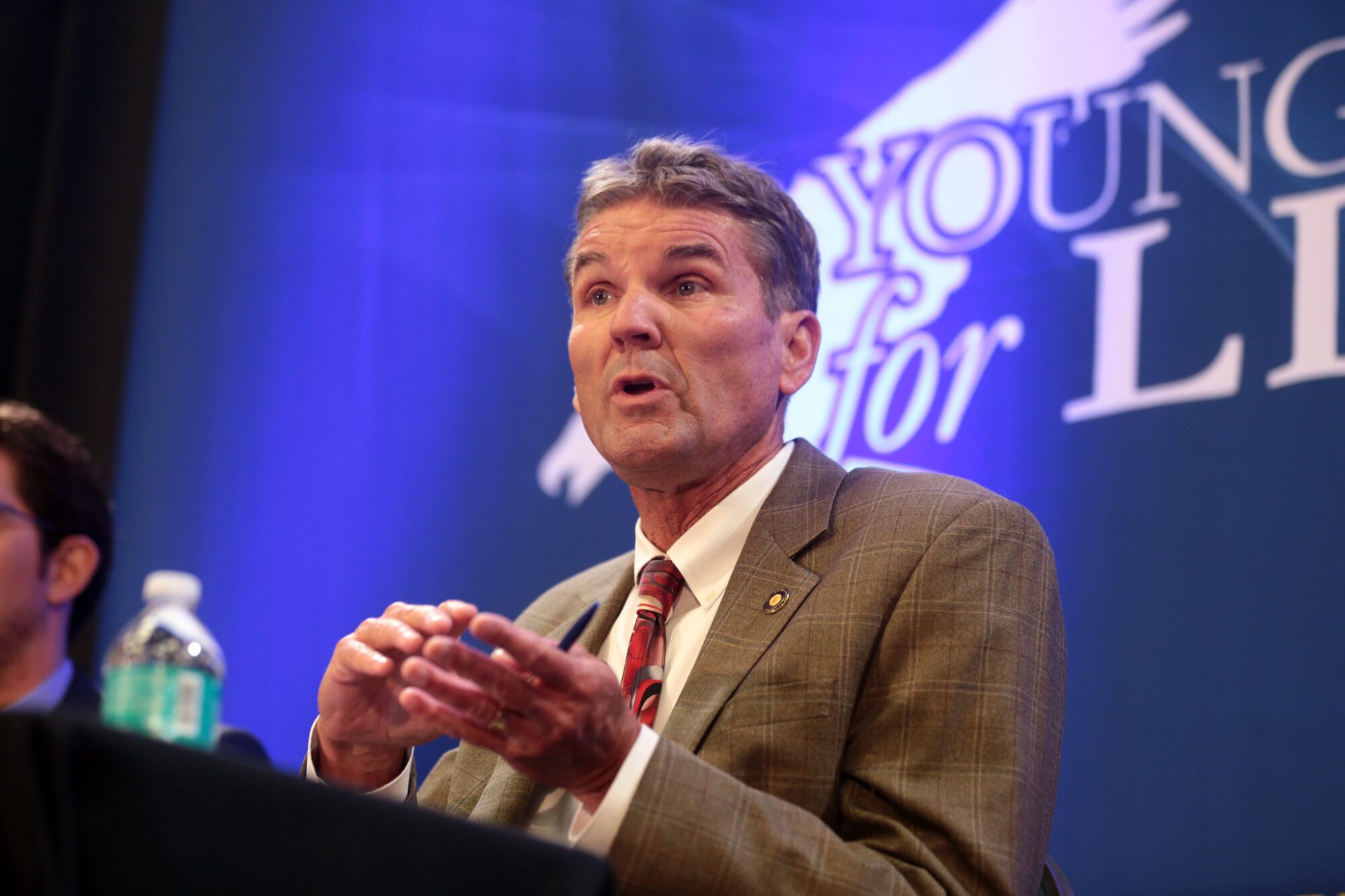

Dennis Linthicum spread unfounded claims about the 2020 election and sued to force Oregonians to vote in person. He’ll face Democrat Tobias Read in November to be secretary of state.

| May 28, 2024

Editor’s note (Nov. 7): Democrat Tobias Read defeated Republican Dennis Linthicum in the November general election.

The moderator of an April candidate forum hosted by the City Club of Central Oregon wanted to know: Could the Republicans running for secretary of state confirm that, if elected, they’d certify the results of Oregon elections, even when their preferred candidates lose?

That would depend, candidate Dennis Linthicum responded. He’d first want to check with citizen activists.

“No detective will ever find a body in the backyard if he doesn’t look,” said Linthicum, who is currently a state senator representing a district in south central Oregon. “So, at some point, the public is the best lookers we have. They’re out there, they’re investigating. You’ve got people doing the math. You’ve got people chasing ballots and understanding how ballot harvesting has been harming the public.”

At no point in the forum did Linthicum provide evidence of widespread voter fraud in Oregon—there isn’t any—but that has never stopped him. He is part of a nationwide network of conservative officials and cultural influencers who have stoked election-related conspiracies for years now. Three years ago, he joined lawmakers from around the country in calling for an audit of the 2020 presidential election in all 50 states based on unspecified “fraud and irregularities.”

Linthicum last week easily captured the GOP nomination to be secretary of state, Oregon’s top elections official. The office oversees voter registration and voting procedures, and is also charged with certifying election results.

In November, he’ll face Democrat Tobias Read, currently Oregon’s treasurer, who won his own contested primary last week. (The sitting secretary of state is not running.) Read is the clear favorite in this blue-leaning state, which hasn’t elected a Republican in any statewide race since the secretary of state election in 2016.

Mirroring many of the conspiracy theories pushed by allies of Donald Trump since his loss in the 2020 presidential race, Linthicum traces his unfounded claims to mail voting. He’s running on a platform of eliminating vote by mail, and forcing people to only vote in-person.

“There’s a giant chain of custody problem that’s associated with mail-in ballots,” he said at the April forum. “Balloting by ID, in a local precinct, where it can be managed by locals within the community, is the appropriate way to go.”

This change would end a system that Oregon pioneered a quarter-century ago, and one that has both boosted turnout in the state and inspired a policy shift in many other parts of the country. Oregon first allowed mail ballots in 1987, and in the 1990s it became the first state to adopt universal mail voting, meaning that every registered voter got a ballot in the mail. Today, most states allow any eligible voter to vote by mail. Eight states have universal mail voting.

Read, the Democrat, told Bolts he’ll work to protect the system if elected. “Oregonians are rightly proud of our long tradition of vote-by-mail elections,” he said. “I will look to strengthen it by making it more transparent and accessible, and protect it from cynical efforts to undermine our elections.”

Bolts reported in April that Read was running on incremental changes that would make it easier for people to vote. For example, he wants to set up a system that would send voters digital notifications of the status of their mail ballot so that they can follow it and feel confident it counted.

Voting by mail has grown to be very popular in Oregon, to the point that only a slim minority of people there vote in person anymore. Paul Gronke, who has been conducting public opinion research on this topic for nearly a decade, told Bolts that prior to Trump, voting by mail was “really overwhelmingly supported” in Oregon, among Republicans and Democrats alike.

“There were really very few questions,” said Gronke, a professor at Reed College and director of the Portland-based Elections & Voting Information Center. “Everybody loved it because we’d really adapted to it.”

But many conservatives soured on mail voting starting in 2020, and circulated widely debunked conspiracies that it enabled mass fraud. GOP-run states adopted new restrictions on mail voting and ballot drop boxes, which are used to collect mail ballots. No state has outright banned mail voting nor has any state with universal mail voting rolled that back, including conservative Utah.

The unfounded claims about mail voting have resonated in parts of Oregon—the May 21 primary saw some protesters gather in Bend to demand an end to mail voting, for instance—even if the state was not competitive in 2020.

Linthicum has had a hand in that. Alongside some conservative allies, the lawmaker filed a lawsuit in 2022 looking to strike down Oregon’s vote-by-mail system.

The lawsuit alleged that mail voting is so unsafe and opaque that its availability violates citizens’ civil rights under the U.S. Constitution. It asked the courts to end mail voting altogether in Oregon, even as it contained no proof about issues with mail voting in Oregon. Relying largely on the debunked conspiracist documentary 2,000 Mules, it argued that “organized criminal” officials may be covering up fraud, and that the public cannot know “whether our elections are indeed safe.”

That suit was dismissed by a federal judge last year, and the U.S. Supreme Court last week declined to take up the case.

Linthicum has still repeated his claims against mail voting on the campaign trail. “Today, people, not necessarily citizens, can vote using a centralized non-transparent black box using mail-in ballots with nothing but a signature to validate the authenticity of the vote,” he wrote in a campaign newsletter in January. (Noncitizens are barred from voting in federal elections everywhere, and studies show these laws are not broken at any significant scale, but Republican politicians have increasingly spread false information on the issue.)

Linthicum did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.

As secretary of state, he would be limited in his ability to force the reforms he envisions.

The daily tasks of Oregon election administration are handled by county-level officials. The secretary of state acts largely as a coordinator, and has no unilateral power to make significant changes to the election system. That work mainly falls to the state legislature, and if he wins in November, Linthicum would very likely have to contend with a statehouse controlled by Democrats, who strongly support mail voting. (Oregon voters are also electing the entire state House, and half of the state Senate, this fall. Democratic governor Tina Kotek, who won by just three percentage points in 2022, is not up for election until 2026.)

The secretary of state may be involved in future litigation around mail voting. The office was named as a defendant in the lawsuit filed by Linthicum and others in 2022, and the state defended the system’s constitutionality. The secretary of state’s responsibility to certify election results may also prompt some chaos if Linthicum wins, given his hints that he could look to stall the process.

In other contexts in which election deniers have refused to certify elections, courts have stepped in, and here, too, Oregon’s liberal supreme court looms as a backstop. But Trump allies have theorized that creating a “cloud of confusion” around results can gain them an advantage.

Election observers also commonly warn that individuals gaining a platform to spread false narratives about election integrity has an insidious effect on people’s confidence in democracy.

“The challenge our system faces in the U.S. is not the reality of election fraud, or weakened election integrity, but the belief that voters have,” said Gronke, the professor and researcher.

He added, of Linthicum, “Having someone with the bully pulpit like that can exacerbate that level of distrust.”

While calling on conservative activists to help prove election fraud, Linthicum has also directly embedded himself within that corps. He was the only sitting elected official to put their name on the lawsuit against vote-by-mail, joining a group of plaintiffs that included advocates with the conservative citizen organization Free Oregon and the Election Integrity Committee of the state Republican Party.

Linthicum has found other allies within the halls of power in some of his endeavors. Two Oregon lawmakers, state Senator Kim Thatcher and state Representative Lily Morgan, joined him in signing the 2021 letter demanding an audit of all states’ presidential results.

Linthicum’s opposition to his state’s government has led him to champion the efforts of some in rural Oregon counties to secede from the state. He filed legislation seeking to force the state to open discussion on a far-fetched plan to join eastern Oregon with Idaho. Thirteen counties have approved advisory local measures to signal support for secession, including Klamath County, where Linthicum lives.

Linthicum’s bid for higher office comes after a tense 2023 legislative session that saw him and nine other Republican state senators stage an extended statehouse walkout in protest of Democratic legislation on abortion, gun rights, and transgender health care. Voters in 2022 had passed a ballot measure to punish absenteeism among lawmakers, and the state supreme court confirmed in March that Linthicum was barred from seeking reelection as a result.

Democrats have used their authority in Salem over the last decade to pass a string of reforms to make democracy more inclusive, extending beyond just mail voting. Perhaps most significantly, the state was the first in the country to adopt an automatic voter registration program for eligible voters, and is now among a handful of states pushing the federal government to let that program grow even further.

Read, who is now running to keep Democrats in control of the secretary of state’s office, says he wants to build on that work, proposing tweaks but no big overhaul, Bolts reported last month.

“Any effort to make it easier for people to vote, to remove barriers, is a good thing,” Read said.

Phil Keisling, who helped champion the creation of universal mail voting as secretary of state in the 1990s, noted that this issue has long been partisan. Initially, he told Bolts, it was Oregon Republicans who pushed to codify universal mail voting in state law, and Democrats, including Keisling at first, who resisted the idea. “Heck, I voted against it. I didn’t know anything about it,” he said. By the mid-90s, he was sold, but, he added, “I was spending most of my time trying to convince Democrats this wasn’t a nefarious Republican plot.”

Keisling, who now advocates for this reform nationwide as chair of the National Vote At Home Institute, said that the program over time became very normalized in Oregon. Of Linthicum’s call to eliminate mail voting, he said, “I think it’s an issue the majority of Oregonians are going to pretty soundly reject.”

“If you ask most in the state what they think of mail voting,” he said, “their response will be, ‘Don’t you dare take it away, we love it.’”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom: We rely on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.