Pennsylvanians Are About to Decide Who Will Oversee the 2024 Elections

Where you live shouldn’t determine if your ballot counts, but in Pennsylvania county officials have wide discretion over drop boxes and mail voting. They’re on the ballot on Nov. 7.

| October 26, 2023

Bob Harvie was thrust on the national stage in late 2020 when Donald Trump, in an effort to find any angle to cling to the presidency, unsuccessfully sued Bucks County, a populous suburb of Philadelphia, demanding that thousands of mail ballots be thrown out.

As one of the two Democrats on the three-member county commission, Harvie was responsible for the county’s voting procedures and he wanted people to vote safely during the pandemic. With his support, Bucks County installed ballot drop boxes and notified roughly 1,600 voters that they had made a clerical mistake on their mail ballot such as forgetting to date their envelopes, giving them the opportunity to correct it—a common procedure known as ballot curing.

“The Republican Party and the Trump campaign wanted things done a certain way, we didn’t do things the way they wanted to, so they sued us. Clearly we’d followed the law because we won all these suits,” recalls Harvie, who is running for reelection in two weeks. The race will determine what party controls Bucks County’s commission during the next presidential election.

Democrats gained control of the commission in 2019 for the first time in decades, one of five flips in eastern Pennsylvania counties with more than 2 million residents combined. The results gave Democrats near total control of the ring of counties around Philadelphia. Their new majorities approved relatively expansive voting procedures, and in late 2020 they effectively created a suburban firewall against Trump’s efforts to get officials in blue counties to throw out ballots and resist certifying the results.

Pennsylvania leaves county officials with a lot of discretion to decide how to run elections. They have tremendous leeway in particular when it comes to deciding the modalities of voting by mail. The state provides little binding guidance on whether a county needs to have a ballot drop box, let alone how many drop boxes to have or how accessible they should be. County officials also decide whether to notify voters whose ballot risks being rejected because of a minor mistake.

This has produced a disconcerting patchwork of policies. “You can have boards of elections that are 15 minutes apart and yet the rules are so different,” says Kadida Kenner, executive director of New PA Project, an organization that focuses on boosting voter registration and turnout.

In the lead-up to the 2020 and 2022 elections, many counties adopted more restrictive rules, including not installing drop boxes and not letting voters correct mistakes on their envelopes. The decisions did not always fall neatly on partisan lines, and voting rights organizations have targeted Democratic boards for tossing out too many ballots, including in the city of Philadelphia. But, by and large, Republican politicians since 2020 have been more likely to oppose procedures that facilitate mail voting. Even Dauphin County (the bluest county under GOP control) has not allowed ballot curing, offering a glimpse into what the voter-rich suburban ring around Philadelphia would have looked like had Democrats not made major gains in 2019.

Harvie points to the rules in place in other parts of Pennsylvania to lay out the stakes of his county’s Nov. 7 elections.

“If Republicans are in control of the board of elections in 2024,” he told Bolts, “I don’t have any doubt that a lot of the things we put in place will be gone.”

If the county reversed its approach on curing, he says, officials would likely reject thousands of mail ballots without first reaching out to voters to say there was an issue with their ballot. “The dangerous part is that people won’t know that their votes aren’t counted,” he says. “You’re gonna think, ‘Oh, I guess I voted, I didn’t do anything wrong.’ You wouldn’t even know that you had been denied.”

Voters in other counties will also be deciding the shape of their county governments on Nov. 7, which means that they’ll also be choosing who will run next year’s elections in this critical swing state—and under what policy.

Republicans could flip closely divided counties like Bucks, but they’ll also test Democratic gains in counties like Chester that have swung dramatically blue since 2019 after staying faithful to Republicans for decades in local elections. Democrats, meanwhile, have some opportunities to gain ground, for instance in Dauphin and Berks.

The results will shape how easy it is for millions of Pennsylvanians to vote—especially by mail—and the odds that their ballot will be rejected.

“If newly elected county governments in Pennsylvania remove drop boxes, if they remove the ability for voters to cure their ballots, they’ll make it even harder for eligible voters to have the votes counted,” said Philip Hensley-Robin, executive director of Common Cause Pennsylvania, a nonpartisan organization that promotes wider access to voting.

“That could impact tens or hundreds of thousands of voters in the 2024 election and change the result of the election,” Hensley-Robin added.

The results will also inform which counties are susceptible to not certify next year’s elections. Plenty of commissioner candidates who’ve amplified Trump’s false claims of widespread irregularities advanced past the GOP primaries, often in staunchly red counties, Bolts reported in May.

Among them are Christian Leinbach and Michael Rivera, the two Republican commissioners who run Berks County, a jurisdiction of more than 400,000 people located 50 miles west of Bucks County. Last year, they refused to certify their county’s election results because they wanted to exclude some valid mail ballots from their counts; a state court ultimately forced them to certify the results.

Leinbach and Rivera are now facing Democratic challengers Jesse Royer and Dante Santoni, who told Bolts in separate interviews that they’re worried about 2024: They think the GOP incumbents, if they remain in control, could once again placate election deniers next year and try to toss out results.

“The most important thing is that we have a board of commissioners that endorses the winner of a campaign,” Santoni told Bolts. “When the election is over, we accept the results. We think that that distinguishes us from our opponents. We talk about a lot of issues—roads, economic development—but without democracy, all those issues don’t mean a whole lot.”

Leinbach and Rivera did not reply to requests for comment. GOP commissioners are also running for reelection in Fayette and Lancaster counties after similarly stalling certification of the 2022 primaries.

Royer and Santoni, the Democratic challengers in Berks, also laid out how they would ease mail voting. Both want to notify voters if their ballots have an error; Berks County’s Republican commissioners defeated a motion earlier this year for the county to provide such information to voters. “We need to make sure that people who are trying to cast their ballots are given every opportunity to do so,” Royer said.

Both Democrats also want to increase the number of ballot drop boxes set up in the county; Royer pointed out that it’s critical to make them widely accessible given that the county has poor public transportation. Both also oppose the county’s current policy, unusual in this state, of stationing armed sheriff’s deputies at ballot boxes; they warn that this may intimidate some voters, a position that Common Cause and other civil rights groups share.

Unlike in Berks County, voters in Bucks County currently do not have to interact with armed law enforcement to cast a ballot. Harvie, the Democratic commissioner, says he wants to keep it that way.

Harvie also worries that Bucks County could go the way of Berks County in terms of objections to election certification. He stresses that the Bucks County Republican Party is chaired by Pat Poprik, who became a false presidential elector for Trump in December 2020 and has clout over local GOP politics. Conservatives have recently taken the county by storm with major upheavals to local public schools via book bans and restrictions on LGBTQ+ students, and Democrats are tying these far-right gains on local school boards to the commissioner race.

The Republican candidate who is vying to join and flip Bucks County’s commission, County Controller Pamela Van Blunk, did not reply to a request for comment.

Voting rights attorneys in Pennsylvania told Bolts that they are less anxious about counties not certifying results than they are about thousands of mail ballots being tossed, since state courts are likely to intervene in the former scenario. County officials are not meant to have discretion to reject valid results, says Marian Schneider, who works on voting rights policy at the ACLU of Pennsylvania. She says that their task is merely “ministerial,” but that the ACLU will be vigilant.

Still, Hensley-Robin of Common Cause is worried that Trump, should he be the GOP’s presidential nominee in 2024, would seek to weaponize delays and confusion in a replay of 2020. “When we see individual counties delaying certification or messing with voting machines, that spreads distrust in the election system, and that builds misinformation, which can result in moving to overturn an election,” he says.

Another fake Trump elector, Sam DeMarco, is currently a county commissioner in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania’s second most populous county. He holds an at-large seat that’s effectively reserved for the GOP, which makes it certain he will win a new term on Nov. 7. Should Republicans also win the unusually heated race for county executive, this would give them control of the county’s board of elections, which is made up of the county executive and the two at-large members.

The Republican nominee for county executive, Joe Rockey, has distanced himself from Trump. But any small voting policy change in this populous county—where Biden won 150,000 more votes than Trump, double his statewide margin—would have important ramifications in 2024.

Pennsylvania in 2019 enacted Act 77, a bipartisan law that greatly expanded the availability of mail voting, but it did not set statewide guidelines for how counties should approach vital questions related to mail-in voting, including how to deal with clerical errors made by voters. Schneider regrets, for instance, that “there really is nothing in the election code that addresses what happens if a mistake has been made on the outer envelope.”

State courts have stepped into this void since 2020, but in ways that have only compounded the importance of what county officials decide with regards to ballot curing.

For one, Republicans have won legal battles ensuring that mail ballots with small errors will get tossed if they aren’t fixed in time; in the lead-up to the 2022 midterms, the supreme court ordered officials not to count a ballot if the voter forgot to write a date, even if the ballot arrived on time. “There are new things that can disqualify you,” Hensley-Robin warns. Due to this higher standard, he says, thousands of ballots risk being tossed in 2024 that would not have been in 2020—unless voters get to cure them first.

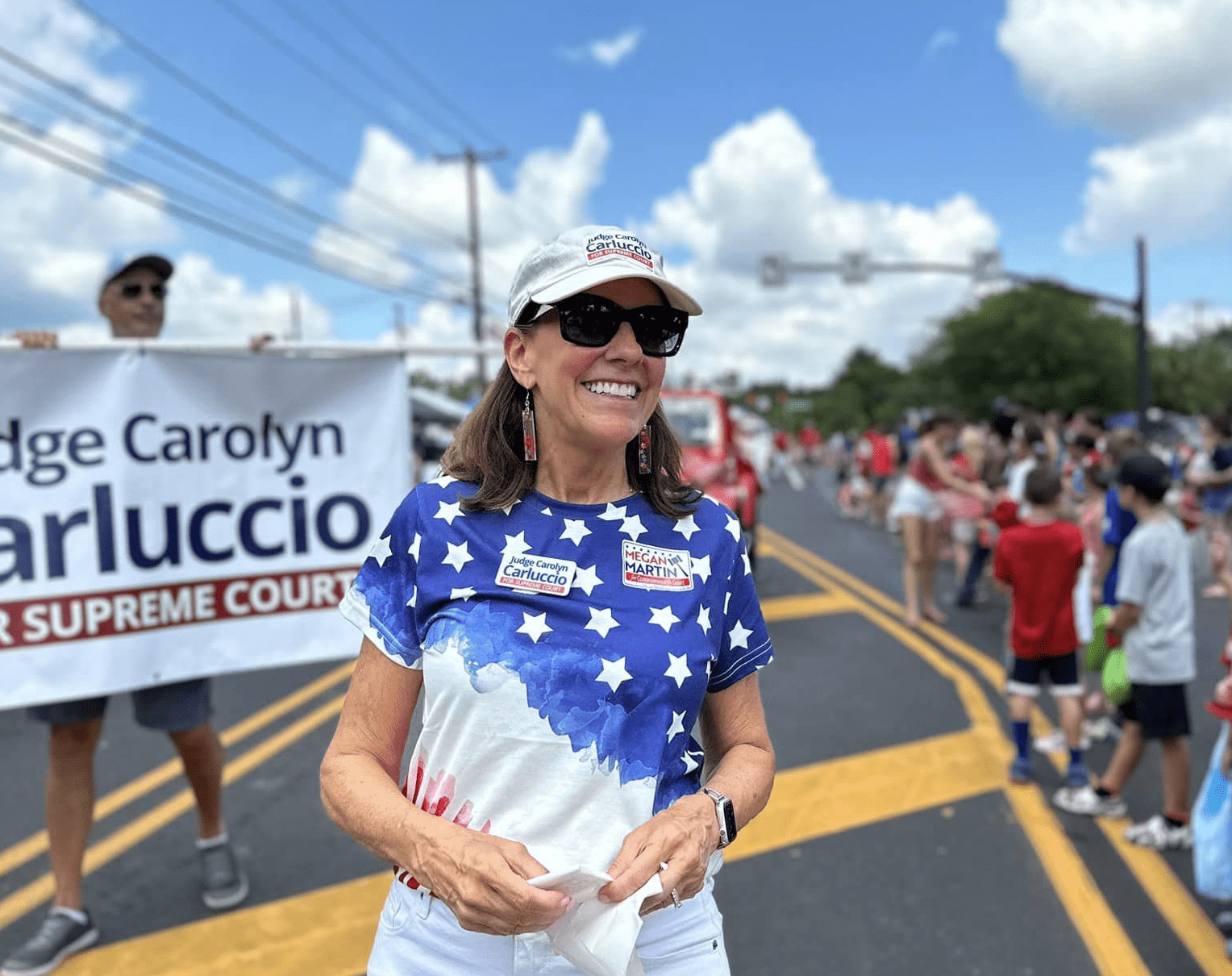

Pennsylvanians are also electing a new state supreme court justice this fall, with the two candidates staking very different opinions on how permissive courts should be toward mail voting.

Moreover, courts have confirmed that there is no statewide rule regarding whether counties must help voters correct their mistakes. In 2022, they rejected a Republican lawsuit demanding that all counties stop the practice of ballot curing altogether. The decision was a relief for voting rights advocates since it meant boards could still choose to let voters cure their ballots, but it also entrenched the current status quo that leaves the matter entirely to counties’ discretion.

Advocates for ballot access are deeply frustrated that the state has been reduced to this mosaic of disparate policies. Policies should not differ so starkly from one county to the next when it comes to the ease of mail voting, they say. “This patchwork from county to county really confuses voters and makes them unsure of the rules in the system,” says Hensley-Robin.

Kenner, of New PA Project, says this fragmentation also stands as a big obstacle for organizations like hers that are working on the ground to drive up turnout.

“It gets very confusing for a statewide organization to be able to subscribe to the various rules that board of elections have in each county,” she told Bolts. “As we’re preparing to do our GOTV efforts, we have to make sure that all scripts are different for each county… It also makes it tough when we’re doing voter registration, and we’re dropping off completed voter registration forms to various boards of elections and they all have different rules.”

For Hensley-Robin, the remedy cannot just be persuading individual county commissioners throughout the state of Pennsylvania to ease ballot access. He is advocating for the state to adopt House Bill 847, which would impose new statewide mandates, for instance when it comes to guaranteeing that counties give all voters a chance to correct their ballots.

“Ballots should not be disqualified for failure to meet a clerical or technical standard,” says Hensley-Robin. “If voters make a small mistake in terms of failing to date a ballot or put a signature or have a secrecy envelope, they should have an opportunity to fix those. There needs to be a requirement for all counties to notify voters actively within 24 hours of receipt about one of these defects so that they have an opportunity to cure it immediately.”

Without such mandates, the Nov. 7 elections have graver stakes than anyone wishes on them.

“Where you live shouldn’t determine whether you have an opportunity to have your vote counted,” he added.

Stay up-to-date

Pennsylvania Votes

Bolts is closely covering the ramifications of Pennsylvania’s 2023 elections for voting rights and criminal justice.