Philadelphia D.A. Race Could Ramp Up the War on Drugs

Larry Krasner has been dropping drug possession charges at a growing pace. But his challenger in the May 18 primary wants to send these cases to drug court.

Maura Ewing | April 12, 2021

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

Larry Krasner has been dropping drug possession charges at a growing pace. But his challenger in the May 18 primary wants to send these cases to drug court.

The support of friends, family, and social service providers catalyzed Sterling Johnson’s recovery from substance use disorder. “When they looked at me and they saw hope in me instead of treating me like shit,” he said. “I would say that dignity, respect, having people believe in you. Those are the things that make you want to change.”

Johnson is a lawyer and housing advocate in Philadelphia, where District Attorney Larry Krasner has made strides toward decriminalizing simple drug possession by dismissing an increasingly large portion of these cases. Johnson sees this as key to decriminalizing substance use.

“Let’s humanize every single person,” he said. “You don’t put them in a box and they get better from the box.”

Philadelphia could step back into the mainstream of the war on drugs should Krasner lose the May 18 Democratic primary—a de facto general election in this deeply blue city. His opponent is Carlos Vega, a career prosecutor who Krasner fired upon taking office. Vega has more of a law-and-order stance; he favors sending drug possession cases to drug court, rather than dropping charges outright. Drug courts can bring alternatives to incarceration, but their eligibility is restricted, and people remain under the threat of prosecution or incarceration if they relapse during treatment.

“Correctional facilities are detrimental to a person’s health … Being incarcerated has a huge impact on a person’s life, even more than the use disorder,” said Danielle Ompad, professor of epidemiology at New York University’s School of Global Public Health. She said that prosecuting drug offenses isn’t working and that “we could be putting that money into poverty alleviation, building an economic safety net.”

Upon taking office, Krasner stopped prosecuting marijuana possession. Then, in late 2019, he established a policy of dropping every drug possession charge if the person shows proof of participating in treatment. The office defines treatment broadly, and does not require the recovery program to be court-monitored. Attending a Narcotics Anonymous meeting would suffice for someone caught with cocaine, for example, and such meetings are free and widely offered in the city. The office also does not wait to see if the person successfully completes the program before dismissing the case, a marked contrast with drug courts.

“We weren’t going to keep a hammer over their head to be sure that they completed X number of days,” Krasner told The Appeal: Political Report. “We know that often people are not ready for treatment, or treatment fails them the first time. But at least go so that you know where to get [it].”

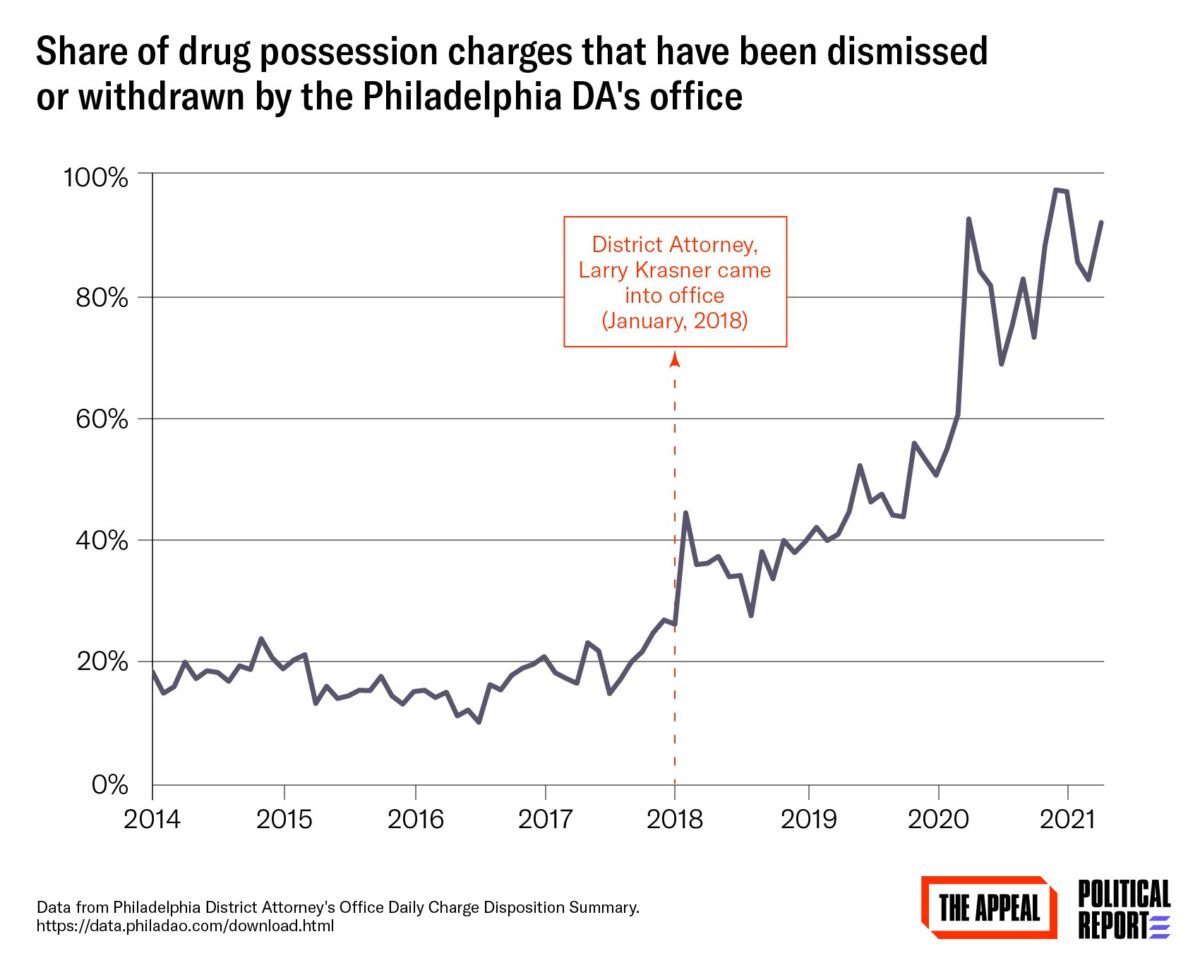

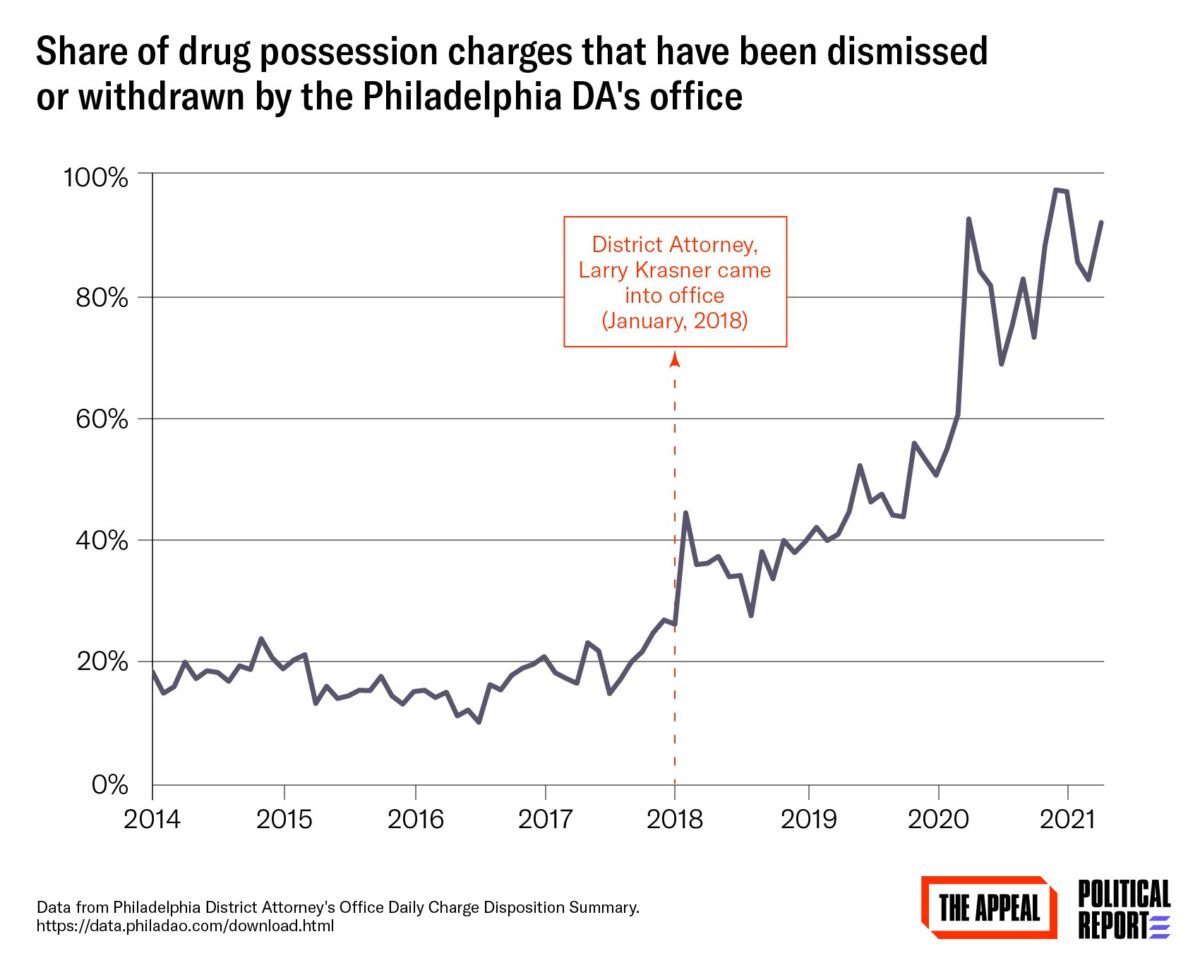

The share of drug possession charges that were outright dismissed by the DA’s office climbed as soon as Krasner took charge in January 2018. It then rose again after he made it a policy in late 2019 to drop charges for people who seek treatment regardless of whether they enter drug court or complete a program.

Comparing January through March 2020 (before local courts shut down due to COVID-19) to the equivalent time period in 2017 (the last year before Krasner entered office), the share of drug possession charges that were dismissed increased from 19 percent in 2017 to 54 percent in 2020. This jump corresponds to hundreds of dismissed cases.

The share of dismissed charges surged further when the pandemic began, but pandemic data is tricky because courts were non-functioning and many prosecutors dismissed low-level cases more broadly. Between January and March of 2021, as Krasner called for police to make fewer arrests for low-level crimes, the office dismissed 87 percent of drug possession charges.

Krasner has made other changes to enhance harm reduction, like declining to prosecute anyone for possessing buprenorphine, a drug that is prescribed to quell cravings for someone weaning off opioid use but is also sold on the black market. Also he sanctioned fentanyl test strips, which are used to detect the lethal chemical and were previously considered drug paraphernalia. And alongside other city officials, he has advocated for the construction of a safe injection site to reduce overdose deaths.

Vega says he will continue to not prosecute cases involving marijuana possession. When it comes to other forms of substance use, though, he wants to take the Philadelphia DA’s office in the opposite direction. He has spoken against bringing a safe injection site to the city, and he is campaigning to return to the long-established drug diversion programs administered by a drug court, where a person’s chance to circumvent incarceration depends on whether they can abide the program’s conditions and achieve sobriety.

“If you’re caught with a drug that I believe is going to destroy your life, lead you to a dark place and also affect the community, I’m going to put you into a program,” Vega told the Political Report. “And once you complete that program, get the help you need, the counseling you need, I drop the charges, and I seal that record.”

However, this type of court-monitored diversion program is increasingly selective, only admitting people with no prior convictions, and it comes with onerous requirements such as reporting for urine tests that can impede a person’s ability to make a living. Critics say that these programs often lead to incarceration when people trip up and fail to meet those conditions—often with steeper sentences than if they had just been sentenced in the first place.

“For people who have substance use disorders, relapsing can be part of their recovery,” said Ompad.

Some local activists and public health advocates are also pressing Krasner to go further and dismiss drug possession arrests without conditions. “Most people who use drugs don’t need treatment,” said Ompad. “If someone is picked up for marijuana or cocaine possession and they use maybe once a month or once a week, they don’t really have a substance use problem.”

Brooke Feldman, a board member with the Philadelphia-based harm reduction nonprofit Angels in Motion, says she supports what Krasner is doing, but thinks that he should drop the treatment requirement, however small it may be. “Mandating something isn’t the way to go,” she said.

She explained that one negative experience with a treatment facility can become a barrier to recovery—so a person should only enter when they’re ready, and through a program that is right for them. “If someone goes to a meeting because they had to, it just gives them a picture of something that they don’t want to do in the future. That can set them back,” she said. “Or if someone goes and gets an assessment for treatment and has a negative experience, they sat and waited for eight hours, in withdrawal, got treated like shit, in the end was told, ‘Sorry we don’t have any beds available for you.’ That kind of stuff sets people back.”

Krasner has also faced criticism from the Philadelphia Bail Fund, which slammed him in a July 2020 report for asking judges to set impossibly high bail for people charged with, among other things, drug possession with intent to distribute. This is a charge that Krasner doesn’t plan to stop prosecuting, but he had implied it would no longer trigger pretrial detention when he made promises to only seek bail for violent offenses.

Other prosecutors nationwide have moved toward policies of not prosecuting drug possession, including DAs in Boston, Seattle, and Baltimore, where State Attorney Marilyn Mosby’s office halted prosecuting drug possession during the pandemic as a measure to reduce jail population size. In response to a subsequent drop in crime rates, Mosby’s office recently announced that these changes are permanent.

Taking it a step further, in a January 29th letter to his constituents, newly elected Travis County, Texas, District Attorney Jose Garza said that he would not prosecute people for possessing small amounts of drugs, but also for selling those amounts, unless the case includes violent conduct.

In Oregon, Multnomah County (Portland) District Attorney Mike Schmidt was a strong advocate for the new state law that decriminalizes drug possession, making it the first state in the country to do so. The 2020 reform was inspired in part by Portugal, which decriminalized personal amounts of drugs in 2001.

Krasner says he would eventually like to have a similar model. In Portugal, if a police officer finds a person in possession of drugs, rather than send that person to jail, they typically direct them to a local commission that includes a lawyer, social worker, and a doctor. This team will educate the person about available treatment, including medical and social services.

The primary rationale for Portugal’s law change was to destigmatize drug use, encourage treatment for those who needed it, and cut down on needless incarcerations. Since it was implemented, drug use has decreased, and the number of overdose deaths has declined. Meanwhile, the number of people entering drug rehabilitation programs has increased.

Portugal’s government implemented this system in the midst of a heroin epidemic that Philadelphia is mirroring today. The city is one of the hardest hit by the opioid overdose epidemic. A staggering 1,150 people were reported to die from overdose in Philadelphia in 2019, with 80 percent of them attributed to opioids.

This article has been corrected to reflect that Krasner’s predecessor did not have a policy of declining to prosecute marijuana charges; Krasner established this policy upon taking office. This article has also been updated to include that Vega says he would retain this policy and not prosecute marijuana cases.