Prison Officials Routinely Deny Hearings to Terminally Ill New Yorkers

The frequent refusal to send medical parole cases to the state board has frustrated advocates and raises questions about the murky criteria preventing most sick people from making their case.

Victoria Law | April 14, 2022

This is the second installment of a collaboration between Bolts and New York Focus on the opaque institutions that make up New York’s parole system. Read the first installment here.

If anyone were too sick for prison, Jose Medina thought, it would be him.

Medina was 27 years old when he entered New York’s prison system. Four decades later, at 68, he’s still behind bars—and afraid that he may die there.

In 2005, he was diagnosed with lung cancer, which necessitated a complete removal of his left lung and a partial removal of his right lung. He survived the cancer, but was left with chronic respiratory disease and severe emphysema. He now depends on inhalers and, at times, a breathing machine. The following year, he applied for medical parole.

His request was denied.

In 2014, doctors diagnosed Medina with prostate cancer. He now needs a catheter and multiple medications. Five years later, in 2019, the Defenders Clinic Second Look Project at the City University of New York submitted an application for clemency, or a request to the governor to shorten his 50-to-life sentence, on Medina’s behalf.

He never received a response, not even an acknowledgement of receipt. His legal team, headed by Steve Zeidman, sent a follow-up letter on March 16, 2020, two days after the first Covid death in New York—of a woman who, like Medina, had emphysema.

“There’s every indication that he’s the exact sort of person to be most terrified about Covid. He told us he wouldn’t even leave his cell, he was just that terrified,” Zeidman said.

Four days later, the legal team sent another letter, this time requesting medical parole.

On May 15, the prison agency denied the request. “It has been deemed that he is not an appropriate candidate for Medical Parole,” stated the letter, signed by the Department of Correction and Community Supervision (DOCCS)’s chief medical officer John Morley. The letter did not say why Medina was deemed ineligible.

Incarcerated New Yorkers applying for medical parole go through a lengthy process bookended by a medical evaluation at the outset and a final review by the parole board. How decisions are made at these two stages is opaque, but what’s in between is even more of a black box. Two officials within the prison agency—its chief medical officer, Morley, and its head, Acting Commissioner Anthony Annucci—reject many applications after they’ve passed their medical evaluations and before they’ve reached the board, typically with little explanation.

Their refusals have frustrated legal advocates, who question the murky criteria that prevent their clients from at least obtaining a board hearing where they can press their case. Annucci is already under heavy fire for conditions in New York prisons and the approximately 1,000 deaths that have occurred on his watch.

Medina is one of the people whose application got caught in this middle stage. Last November, he was diagnosed with glaucoma in his left eye, causing him pain and blurry vision, which makes moving around difficult. The CUNY legal team is currently gathering records for an independent medical review in preparation for a third medical parole request on his behalf.

Still locked up, afraid he will lose his eyesight completely, afraid he will never meet his daughter outside prison walls, Medina describes “the sad and painful reality of dying alone in a cold dark prison cell.”

“It is an unfortunate reality for all aging prisoners, especially those living with chronic medical conditions,” he told Bolts and New York Focus over email. “I only want to enjoy a moment at the beach with family, go to a movie theater, and experience a nice meal at an upscale restaurant before my departure.”

Most medical parole applications never make it to the parole board

Under New York law, the state parole board can grant medical parole to an incarcerated patient certified by the prison agency as suffering from a malady that renders them “so debilitated or incapacitated as to create a reasonable probability that he or she is physically or cognitively incapable of presenting any danger to society.”

In 2020, as Covid-19 exploded in the prison system, DOCCS received an enormous increase in medical parole requests—1,049 in total. It approved 18.

In a statement to Bolts and New York Focus, a DOCCS spokesperson suggested that many of those applicants may not have been medically eligible. “As the law is currently written, concern that an individual with pre-existing conditions may contract COVID and be at an increased risk for a severe and possibly fatal outcome, is not a basis for medical parole,” the spokesperson said.

In 2021, the number of medical parole applications dropped dramatically, to 82. Of those, 10 people were released.

Applying for medical parole involves many steps. After an incarcerated person or someone on their behalf (such as a family member, attorney, or prison staff member) files an initial request, it must pass four distinct reviews: first by prison clinical staff, who conduct a medical evaluation; then by the DOCCS chief medical officer, who assesses the medical evaluation and the applicant’s risk to public safety; then by DOCCS acting commissioner Annucci; and finally, if the request has made it this far, by the state’s parole board.

If the application makes it to this final stage, the board holds a “medical parole hearing,” with an opportunity for the prosecutor, defense attorneys, sentencing court and the Office of Victim Assistance to provide input. From 2013 to 2017, records obtained by the Vera Institute of Justice show, the board granted medical parole about two-thirds of the time, well over its overall parole approval rate of 23 percent in 2015.

But the vast majority of applications never make it that far.

According to Vera’s report, 476 requests for medical parole were filed between 2013 and 2017. Only 240 were approved by prison staff. Even then, only about half of the remaining pool made it to the parole board. Either the chief medical officer or the commissioner rejected many of those cases, though in some the applicant died while waiting, was released on another form of parole, or completed their sentence.

Applications that are denied by the DOCCS leadership are typically issued form letters signed by the chief medical officer, currently Morley. (The chief medical officer is hired by DOCCS and supervised by its commissioner.) The letters give no reason for the denial—just that “it has been deemed that you are not an appropriate candidate for Medical Parole.”

Zeidman shared a letter sent to one applicant that was originally addressed to another person. That name had been crossed out and his hand-written in. The man died three weeks later.

Last year, a state judge required Morley to explain why he denied the application of Wilfredo Lopez. Lopez had been diagnosed with amyloidosis, and a prison physician had identified the condition as terminal, giving him one to two years to live.

Morley explained to the court why he didn’t consider that grounds for medical parole: “‘Terminal’ suggests a life expectancy of 6 months or less. Mr. Lopez is alive and continues to ambulate with a cane around Greene Correctional Facility.”

Asked what factors go into Morley and Annucci’s decision to deny medical parole applications advanced by others, a DOCCS spokesperson referred New York Focus and Bolts to their directive, which mentions that the medical officer advises the commissioner about the applicant’s medical status. They also said the commissioner looks “to ensure that the law is being adhered to and that a medical parole release would not put public safety at risk.” Prison staff are directed only to conduct a medical evaluation, and not assess public safety, the spokesperson said. The parole board, to which Annucci forwards applications, is also meant to consider safety, though. The department declined to comment on the decision to deny Medina’s medical parole application, stating that it cannot comment on an individual’s health record.

Annucci has led DOCCS since 2013, when then-Governor Andrew Cuomo appointed him, but—even though the position is subject to legislative oversight—he has never been confirmed by the legislature. Governor Kathy Hochul nominated Annucci for the permanent position, but the acting commissioner is now facing significant resistance. Last month, the relatives of ten men who have died in prison issued a joint statement slamming Annucci for, among other things, “the regressive policies that he has promulgated, the scourge of racism and brutality he has sought to sweep under the rug.”

Sometimes, the prison agency’s delays mean that even the few who are granted release still die behind bars. In 2019, the parole board granted medical parole to 75-year-old Edgardo Carlos Gonzalez, who had served 36 years of a 50-to-life sentence. Gonzalez had liver failure, dropping from 175 to 112 pounds, and had been placed in the prison’s hospice ward.

Gonzalez never made it home. Instead, he remained in prison waiting for DOCCS to approve his placement in his family’s home. He was rushed to the hospital, diagnosed with end-stage cancer and—three months after filing a request for medical parole—died in custody.

Dying in prison is the outcome Medina is desperate to avoid.

In August 2020, Medina thought that might happen after he contracted Covid. His condition was so severe that he needed breathing treatments at the infirmary. “I felt as if I was going to die during that devastating experience,” he said.

He recovered, but his health continued to decline. The following August, he was rushed to the hospital. “My heart beat was so fast, over 100, that when I got to the hospital they had no knowledge as to what was wrong with me,” he said. Medical staff found that he had a lung infection and a blood infection. He was given a series of steroids and IV treatments and remained hospitalized for three days.

Last month, on March 24, Medina began experiencing stomach pains, nausea, and heart pains. He said that a prison nurse took his blood pressure and found he had an alarmingly high systolic pressure of 224, which required immediate emergency medical care. He was sent to a hospital and given an IV, hypertension medications, and a CAT scan. Medical staff diagnosed him with prostate and urine infections and determined that he would need gallbladder surgery. Once his blood pressure dropped to 150/80, Medina was sent back to prison.

The next day, he said, his systolic blood pressure again soared to 220, and he was sent to a different hospital. He was treated and, once his blood pressure dropped, returned to the prison.

The following morning, his blood pressure yet again rose to 207. He was rushed to a third hospital, Albany Medical Center, where he spent four days. He spent a fifth night in the prison’s infirmary before returning to his housing unit. He is still experiencing nausea and discomfort in his abdomen.

“My one and last chance to know my father”

Medina signs his emails “Tony the Fighter.” That refers to his numerous illnesses and near-brushes with death, not the fighting of his younger years.

“I’ve spent my majority of my life trying to be a better man,” he told Bolts and New York Focus in one email. He recognizes that, as a 26-year-old in 1980, he was angry, prone to violence, and struggling with heroin addiction, a fatal combination that led him to set fire to the apartment he shared with his girlfriend and stepson. Both died in the fire.

“Not a day goes by in 43 years where I don’t wish the events that took place did not take place and that Laura and Richard were here today living beautiful lives as God intended,” he wrote.

In prison, Medina taught himself to read and write in both English and Spanish. He converted to Christianity, which he describes as a major turning point in his life. He now spends his time creating art and mentoring younger men—which he plans to continue if he’s released. “Being able to enter society now with the lessons I’ve learned would allow me to help other youth from ending up in the same position,” he said.

Studies show that the risk that people released from prison will commit new crimes dramatically declines with age. In New York, just one percent of people released from prison over the age of 65 were sent back to prison on a new conviction, nine times lower than the overall rate.

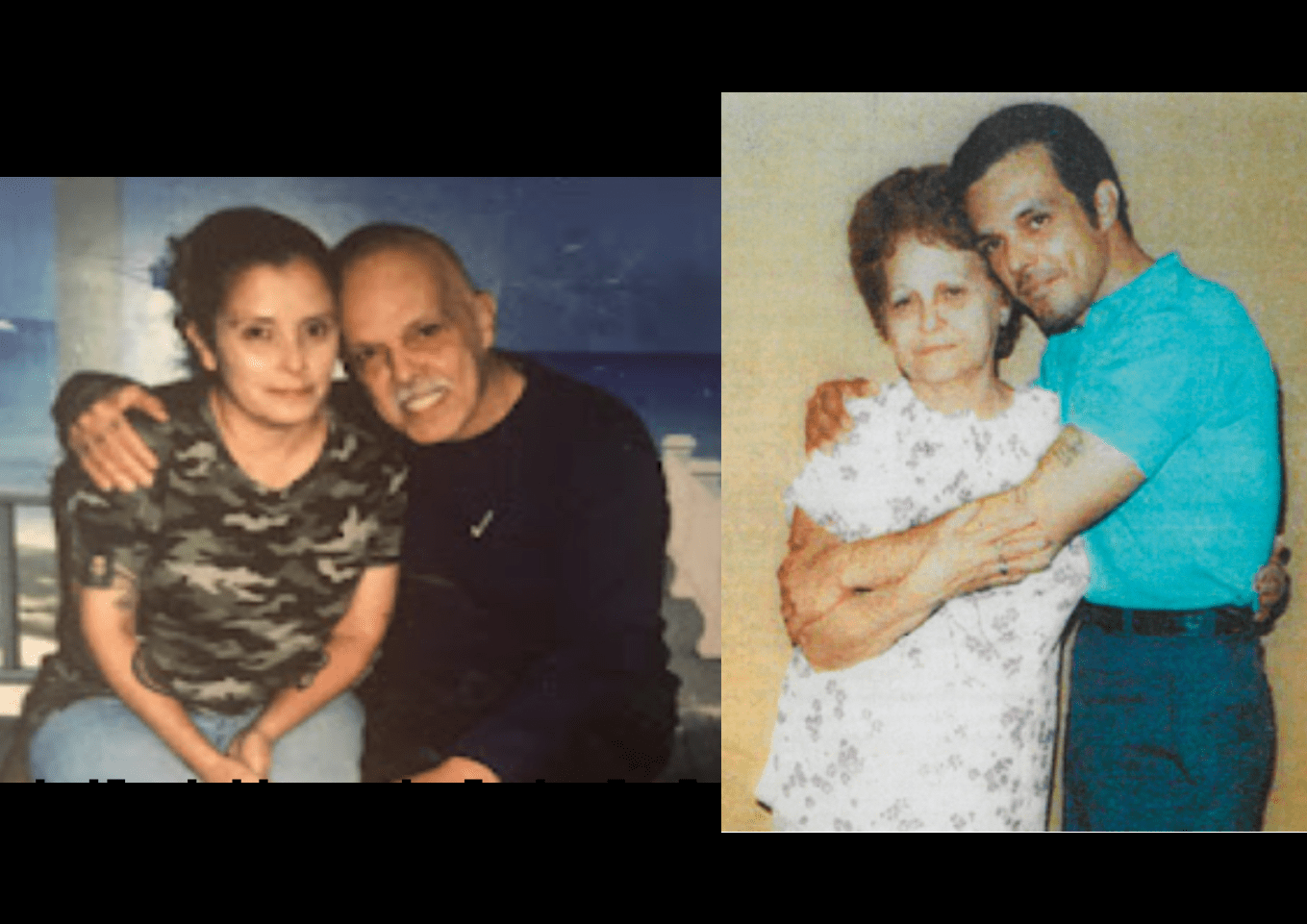

In 2019, Medina connected with his only daughter, Elizabeth, then 47, who had been born while Medina had been incarcerated a previous time. That October, she visited him in prison, the first time the two had ever met. “We ate and took pictures and when it was time to say goodbye, the tears began to rain from my eyes,” Medina recalled. The following day, Elizabeth visited again, this time bringing a food package.

Now, Elizabeth says that she wants to care for her father during his final years. “We never had time, me and my father,” she said in a video plea to Governor Hochul. “He’s very sick. I need every minute…. This is my one and last chance to get to know my father.”